ผู้ใช้:NELLA32/ทดลอง 1

จาซินดา อาร์เดิร์น | |

|---|---|

Jacinda Ardern | |

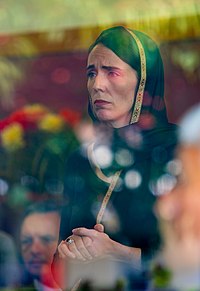

จาซินดา อาร์เดิร์น เมื่อ ค.ศ. 2020 | |

| นายกรัฐมนตรีนิวซีแลนด์คนที่ 40 | |

| เริ่มดำรงตำแหน่ง 26 ตุลาคม ค.ศ. 2017 | |

| กษัตริย์ | อลิซาเบธที่ 2 |

| ผู้สำเร็จราชการ | |

| รอง | |

| ก่อนหน้า | บิล อิงลิช |

| หัวหน้าพรรคแรงงานคนที่ 17 | |

| เริ่มดำรงตำแหน่ง 1 สิงหาคม ค.ศ. 2017 | |

| รอง | เคลวิน เดวิส |

| ก่อนหน้า | แอนดรูว์ ลิตเติล |

| ผู้นำฝ่ายค้านคนที่ 36 | |

| ดำรงตำแหน่ง 1 สิงหาคม ค.ศ. 2017 – 26 ตุลาคม ค.ศ. 2017 | |

| รอง | เคลวิน เดวิส |

| ก่อนหน้า | แอนดรูว์ ลิตเติล |

| ถัดไป | บิล อิงลิช |

| รองหัวพรรคแรงงานคนที่ 17 | |

| ดำรงตำแหน่ง 7 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 2017 – 1 สิงหาคม ค.ศ. 2017 | |

| ผู้นำ | แอนดรูว์ ลิตเติล |

| ก่อนหน้า | แอนเนตต์ คิง |

| ถัดไป | เคลวิน เดวิส |

| Member of the สภาผู้แทนราษฎรนิวซีแลนด์ Parliament for เขตเมาท์อัลเบิร์ต | |

| เริ่มดำรงตำแหน่ง 8 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 2017 | |

| ก่อนหน้า | เดวิด เชียร์เรอร์ |

| คะแนนเสียง | 21,246 |

| Member of the สภาผู้แทนราษฎรนิวซีแลนด์ Parliament for พรรคแรงงาน แบบบัญชีรายชื่อ | |

| ดำรงตำแหน่ง 8 พฤศจิกายน พ.ศ. 2008 – 8 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 2017 | |

| ถัดไป | เรย์มอนด์ ฮั้ว |

| ข้อมูลส่วนบุคคล | |

| เกิด | จาซินดา เคต ลอเรลล์ อาร์เดิร์น 26 กรกฎาคม ค.ศ. 1980 ฮามิลตัน, นิวซีแลนด์ |

| พรรคการเมือง | แรงงาน |

| คู่อาศัย | คลาร์ก เกย์ฟอร์ด (2013–ปัจจุบัน) |

| บุตร | เนฟ เต อะโรฮา อาร์เดิร์น เกย์ฟอร์ด |

| บุพการี |

|

| ที่อยู่อาศัย | พรีเมียร์ เฮาส์, เวลลิงตัน |

| ศิษย์เก่า | มหาวิทยาลัยแห่งไวกาโต (BCS) |

| เว็บไซต์ | jacinda |

จาซินดา เคต ลอเรลล์ อาร์เดิร์น[1] (/dʒəˈsɪndə ɑːˈdɜːn/ jə-sin-də ah-DURN;[2] เกิด 26 กรกฏาคม ค.ศ. 1980) เป็นนายกรัฐมนตรีนิวซีแลนด์คนที่ 40 นายกรัฐมนตรีหญิงคนที่สามของนิวซีแลนด์ และหัวหน้าพรรคแรงงานนิวซีแลนด์ (New Zealand Labour Party) ตั้งแต่ ค.ศ. 2017 เธอได้รับการเลือกตั้งเป็นสมาชิกรัฐสภานิวซีแลนด์ครั้งแรกในฐานะสมาชิกสภาผู้แทนราษฏร แบบบัญชีรายชื่อ (List MP) สังกัดพรรคแรงงาน เมื่อ ค.ศ. 2008 ต่อมาได้รับเลือกตั้งในฐานะสมาชิกรัฐสภาผู้แทนราษฏรประจำเขตเลือกตั้งเมาท์อัลเบิร์ต ซึ่งเธอได้รับเลือกให้เป็นสมาชิกสภาผู้แทนราษฎรประจำเขตนี้มาตั้งแต่เดือนมีนาคม ค.ศ. 2017[3]

อาร์เดิร์นเกิดที่เมืองฮามิลตัน เติบโตและเข้าเรียนในระดับประถมศึกษา―มัธยมศึกษาในมอร์รินส์วิลล์ และมูรูปารา อาร์เดิร์นสำเร็จการศึกษาระดับอุดมศึกษาจากมหาวิทยาลัยไวกาโตเมื่อ ค.ศ. 2001 และได้เข้าทำงานตำแหน่งนักวิจัยในสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรีของอดีตนายกฯ เฮเลน คลาร์ก ต่อมาเธอได้ย้ายมาทำงานในกรุงลอนดอนในตำแหน่งที่ปรึกษาประจำสำนักคณะรัฐมนตรีสหราชอาณาจักร จากนั้น ค.ศ. 2008 อาร์เดิร์นได้รับเลือกตั้งเป็นประธานสหภาพเยาวชนสังคมนิยมนานาชาติ อาร์เดิร์นได้รับการเลือกตั้งเป็นสมาชิกสภาผู้แทนราษฎรสมัยแรกในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2008 เป็นสมัยเดียวกันที่พรรคแรงงานแพ้การเลือกตั้งหลังจากที่เป็นรัฐบาลมา 9 ปี จากนั้นเธอก็ได้รับเลือกตั้งในฐานะสมาชิกสภาผู้แทนราษฎรประจำเขตเลือกตั้งเมาท์อัลเบิร์ต ในการเลือกตั้งซ่อมวันที่ 25 กุมภาพันธ์ ค.ศ. 2017 ด้วยชัยชนะอย่างถล่มทลาย

หลังจากการลาออกของรองหัวหน้าพรรคแรงงาน แอนเนตต์ คิง พรรคจึงได้มีการลงมติในวันที่ 1 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 2017 เลือกอาร์เดิร์นขึ้นมาดำรงตำแหน่งแทน ซึ่งเธอได้รับคะแนนเสียงอย่างเป็นเอกฉันท์ ต่อจากนั้นเพียง 5 เดือน แอนดรูว์ ลิตเติล ก็ประกาศลาออกจากตำแหน่งหัวพรรคแรงงาน หลังจากผลโพลคะแนนความนิยมที่มีต่อพรรคได้ตกต่ำลงอย่างเป็นประวัติการณ์ อาร์เดิร์นจึงได้รับการสนับสนุนอย่างไร้ข้อกังขาเพื่อขึ้นมาดำรงตำแหน่งแทนแทนลิตเติล[4] หลังจากที่อาร์เดิร์นขึ้นมาเป็นหัวหน้าพรรค แรงสนับสนุนที่มีต่อพรรคแรงงานก็ได้กลับมาเพิ่มขึ้นอย่างรวดเร็ว ภายใต้การนำของอาร์เดิร์นพรรคแรงงานได้รับที่นั่งในสภาเพิ่มขึ้นถึง 14 ที่นั่งในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป เมื่อวันที่ 23 กันยายน ค.ศ. 2017 จึงทำให้พรรคแรงงานมีที่นั่งรวมในสภา 46 ที่นั่งเอาชนะพรรคแห่งชาตินิวซีแลนด์ (New Zealand National Party) ที่มี 56 ที่นั่งไปได้[5] ด้วยการจัดตั้งรัฐบาลผสมเสียงข้างน้อยจากการเจรจากับพรรคนิวซีแลนด์เฟิสต์ (New Zealand First) และการสนับสนุนจากพรรคกรีน (Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand) โดยมีจาซินดา อาร์เดิร์นเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรี เธอเข้าพิธีสาบานตนเข้าดำรงตำแหน่งนายกฯ เมื่อวันที่ 26 ตุลาคม ค.ศ. 2017 โดยมีแพตซี เรดดีเป็นผู้สำเร็จราชการ[6] อาร์เดิร์นจึงกลายเป็นหัวหน้ารัฐบาลหญิงที่มีอายุน้อยที่สุดของโลกด้วยวัยเพียง 37 ปี ในวันที่เข้ารับตำแหน่ง[7] หนึ่งปีถัดมาในวันที่ 21 มิถุนายน ค.ศ. 2018 อาร์เดิร์นได้ให้กำเนิดบุตรสาว (ชื่อว่า นีฟ; Neve) ทำให้เธอเป็นหัวหน้ารัฐบาลที่มาจากการเลือกตั้งคนที่สองของโลกที่ให้กำเนิดบุตรขณะที่ดำรงตำแหน่ง (คนแรกคือ เบนาซีร์ บุตโต)[8]

อาร์เดิร์นอธิบายว่าตนเองมีแนวคิดแบบประชาธิปไตยสังคมนิยมและเป็นพวกหัวก้าวหน้า[9][10] รัฐบาลภายใต้การนำของพรรคแรงงานชุดที่ 6 ได้มุ่งเน้นในการจัดการวิกฤตฟองสบู่ที่อยู่อาศัยภายในประเทศ, ปัญหาความยากจนในเด็ก และปัญหาความเหลื่อมล้ำทางสังคม ในเดือนมีนาคม ค.ศ. 2019 หลังจากเหตุกราดยิงมัสยิดในไครสต์เชิร์ช อาร์เดิร์นได้เสนอกฎหมายควบคุมอาวุธปืนเป็นการเร่งด่วนเพื่อตอบสนองต่อเหตุการณ์ดังกล่าว และตลอด ค.ศ. 2020 เธอเป็นผู้นำในการควบคุมและจัดการกับการระบาดของโควิด-19 อาร์เดิร์นนำพรรคแรงงานคว้าชัยชนะในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2020 ด้วยที่นั่งในสภารวม 65 ที่นั่ง เป็นครั้งแรกในประวัติศาสตร์นิวซีแลนด์ที่มีพรรคการเมืองชนะด้วยเสียงข้างมากเกินกึ่งหนึ่งของสภา นับตั้งแต่เริ่มใช้การเลือกตั้งระบบสัดส่วนใน ค.ศ. 1996

ชีวิตในวัยเยาว์ และการศึกษา[แก้]

อาร์เดิร์นเกิดเมื่อวันที่ 26 กรกฏาคม ค.ศ. 1980 ที่เมืองฮามิลตัน ประเทศนิวซีแลนด์[11] เธอเติบโตในมอร์รินส์วิลล์ และมูรูปารา ที่ที่รอสส์ อาร์เดิร์น พ่อขอเธอทำงานเป็นตำรวจอยู่[12] ส่วนแม่ของเธอ ลอเรลล์ อาร์เดิร์น (สกุลเดิม: บัตทอมลีย์) ทำงานเป็นผู้ดูแลการจัดหาอาหารและโภชนาการในโรงเรียน[13][14] อาร์เดิร์นในวัยเยาว์เติบโตขึ้นในครอบครัวชาวคริสต์ในศาสนจักรของพระเยซูคริสต์แห่งวิสุทธิชนยุคสุดท้าย อีกทั้งปู่ของเธอเอง เอียน เอส. อาร์เดิร์น ก็เป็นหนึ่งในบรรดาแอเรีย เซเวนตี (Area Seventy) ของศาสนจักร อาร์เดิร์นเรียนระดับมัธยมศึกษาที่โรงเรียนมอร์รินส์วิล์คอลเลจ[15] ในขณะที่กำลังเรียนอยู่เธอได้รับเลือกให้ทำงานในคณะกรรมการประจำโรงเรียนในฐานะตัวแทนของฝ่ายนักเรียน[16] ในระหว่างที่เรียนชั้นมัธยมอาร์เดิร์นก็ได้เริ่มทำงานในร้านขายฟิชแอนด์ชิปส์ไปด้วย ซึ่งนี่ถือว่าเป็นอาชีพอาชีพแรกที่เธอเคยทำ[17]

อาร์เดิร์นเข้าเป็นสมาชิกพรรคแรงงานตอนอายุ 17 ปี[18] โดยมีป้าของเธอ มารี อาเดิร์น ผู้เป็นสมาชิกพรรคแรงงานมาอย่างยาวนานเป็นคนรับอาร์เดิร์นเข้ามาเพื่อช่วยทำงานหาเสียงให้กับแฮร์รี ไดน์โฮเวน เพื่อชิงตำแหน่ง ส.ส. เขตนิวไปล์เมาท์ ในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 1999[19]

อาร์เดิร์นเข้าศึกษาในมหาวิทยาลัยไวกาโต และสำเร็จการศึกษาปริญญาตรีหลักสูตรการสื่อสาร (Bachelor of Communication Studies; BCS) สาขาการเมืองและการประชาสัมพันธ์ ใน ค.ศ. 2001[20] ในปีเดียวกันนี้อาร์เดิร์นก็ได้ไปเรียนต่างประเทศที่มหาวิทยาลัยแอริโซนาสเตตเป็นจำนวน 1 ภาคเรียน[21][22] หลังจากจบการศึกษาระดับอุดมศึกษา เธอได้เข้าไปทำงานเป็นนักวิจัยในสำนักงานของฟิล กอฟฟ์ และสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรีเฮเลน คลาร์ก จากนั้นเธอได้ออกไปเป็นอาสาสมัครที่นครนิวยอร์ก, สหรัฐ โดยทำงานในโรงทานแจกอาหารให้แก่คนยากจน[23] และร่วมทำงานรณรงค์เพื่อเรียกร้องสิทธิแรงงาน[24] หลังจากนั้นอาร์เดิร์นได้ย้ายมาที่ลอนดอน เพื่อมาดำรงตำแหน่งเป็นหนึ่งใน 80 ที่ปรึกษาระดับสูง ด้านนโยบาย ประจำนายกรัฐมนตรีโทนี แบลร์[25] (เธอไม่เคยพบกับแบลร์ตัวต่อตัวในขณะทำงานที่ลอนดอน แต่ต่อมาใน ค.ศ. 2011 เธอได้พบกับเขาในงานงานหนึ่งที่นิวซีแลนด์ ซึ่งโทนี แบลร์ได้มาร่วมงานด้วย อาร์เดิร์นได้พูดคุยและตั้งคำถามกับเขาเรื่องการตัดสินใจรุกรานอิรัก[26]) และอาร์เดิร์นได้ไปทำงานในลอนดอนอีกเป็นครั้งที่สองในการช่วยทบทวนและตรวจสอบนโยบายในอังกฤษและเวลส์[20][27]

อาชีพทางการเมืองในช่วงต้น[แก้]

ประธานสหภาพเยาวชนสังคมนิยมนานาชาติ[แก้]

อาร์เดิร์นในวัย 27 ปี เธอได้รับเลือกให้เป็นประธานสหภาพเยาวชนสังคมนิยมนานาชาติ (IUSY) จากการลงมติในการประชุมสหภาพประจำปี ค.ศ. 2008 ที่จัดขึ้นที่สาธารณรัฐโดมินิกัน วันที่ 30 มกราคม ค.ศ. 2008 โดยประธานที่ได้รับเลือกจะมีวาระ 2 ปี สิ้นสุดใน ค.ศ. 2010[28][29] การทำหน้าที่ประธานสหภาพระดับนานาชาติทำให้อาร์เดิร์นต้องเดินทางไปหลายประเทศ ไม่ว่าจะเป็น ฮังการี, จอร์แดน, อิสราเอล, และจีน[20] ขณะที่ดำรงตำแหน่งประธานสหภาพมาได้ครึ่งทาง อาร์เดินก็ได้รับเลือกตั้งเป็นสมาชิกสภาผู้แทนราษฎร แบบบัญชีรายชื่อ (List MP) สังกัดพรรคแรงงาน ถึงแม้จะมีงานในรัฐสภามาเพิ่ม เธอก็ยังสามารถดำเนินงานในฐานะประธานสหภาพได้จนครบวาระ 15 เดือนที่เหลืออยู่

สมาชิกรัฐสภา[แก้]

| ค.ศ. | ครั้งที่ | เขต | ลำดับ | พรรค | |

| 2008―2011 | 49 | บัญชีรายชื่อ | 20 | แรงงาน | |

| 2011―2014 | 50 | บัญชีรายชื่อ | 13 | แรงงาน | |

| 2014―2017 | 51 | บัญชีรายชื่อ | 5 | แรงงาน | |

| 2017 | 51 | เมาท์อัลเบิร์ต | แรงงาน | ||

| 2017―2020 | 52 | เมาท์อัลเบิร์ต | 1 | แรงงาน | |

| 2020―ปัจจุบัน | 53 | เมาท์อัลเบิร์ต | 1 | แรงงาน | |

ในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2008 อาร์เดิร์นอยู่ในอันดับที่ 20 ของรายชื่อแคนดิเดต ส.ส. แบบบัญชีรายชื่อของพรรคแรงงาน ซึ่งเป็นอันดับที่สูงมากสำหรับบุคคลที่ไม่เคยเป็น ส.ส. มาก่อน และแทบจะสามารถการันตีได้เลยว่าจะสามารถได้ที่นั่งในสภาอย่างแน่นอน หลังจากที่อาร์เดิร์นกลับจากลอนดอน และได้เริ่มการหาเสียงอย่างเต็มตัว[30] อาเดิร์นก็ได้เป็นแคนดิเดต ส.ส. แบบแบ่งเขต ประจำเขตการเลือกตั้งไวกาโตด้วย แม้จะไม่ได้รับชัยชนะในฐานะ ส.ส. เขตดังกล่าว แต่เธอก็ได้เข้าสู่รัฐสภาในฐานะ ส.ส. แบบบัญชีรายชื่อ จากการคำนวณคะแนนโหวตพรรค ซึ่งเธออยู่ในอันดับที่สูงมากของอันดับบัญชีรายชื่อพรรคแรงงาน[31] เมื่อเข้าทำงานในรัฐสภา เธอกลายเป็น ส.ส. ที่อายุน้อยที่สุดในรัฐสภานิวซีแลนด์ขณะนั้น จนกระทั่งแกเรต ฮุจส์ ได้รับการเลือกตั้งเข้ามาในวันที่ 11 กุมภาพันธ์ ค.ศ. 2010[32]

ฟิล กอฟฟ์ ผู้นำฝ่ายค้านในสมัยนั้นได้สนับสนุนเธอจนได้ขึ้นมานั่งในตำแหน่งสมาชิกแถวหน้าของพรรคแรงงาน โดยให้เธอทำงานในฐานะโฆษกประจำคณะรัฐมนตรีเงาด้านกิจการเด็กและเยาวชน และงานยุติธรรมที่เกี่ยวข้องกับเยาวชน[33]

เธอมักจะปรากฎตัวเป็นประจำในช่วง "Young Guns" ของรายการ Breakfast สถานีโทรทัศน์ TVNZ โดยมักจะออกรายการพร้อมกับซีมอน บริดส์ ส.ส. พรรคแห่งชาติ (และผู้นำพรรคแห่งชาติในเวลาถัดมา)[34]

ในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2011 อาร์เดิร์นได้ลงแข่งขันเลือกตั้งเพื่อชิง ส.ส. เขตออกแลนด์เซ็นทรัลในนามพรรคแรงงาน โดยมีคู่แข่งคนสำคัญ คือ พรรคขั้วตรงข้ามอย่างพรรคแห่งชาติ ที่ส่งนิกกี เคย์ ส.ส. เก่าที่ชนะการเลือกตั้งเขตนี้ในสมัยที่แล้ว และเดนิส รอช ผู้สมัครจากพรรคกรีน เธอรณรงค์หาเสียงด้วยการให้ผู้มีสิทธิเลือกตั้งโหวตอย่างมียุทธศาสตร์ โดยโน้มน้าวผู้ที่มีแนวโน้มจะเลือกพรรคกรีนเทกลับมาเลือกพรรคแรงงาน เพื่อรวมคะแนนเสียงเอาชนะพรรคแห่งชาติที่มีจุดยืนตรงข้ามกับทั้งสองพรรค แต่เมื่อผลการเลือกตั้งเขตออกมา เธอก็ยังไม่สามารถเอาชนะเคย์จากพรรคแห่งชาติไปได้ด้วยผลต่าง 717 คะแนน อย่างไรก็ตามอาร์เดิร์นก็ยังคงได้รับเลือกเข้าสู่สภาในฐานะ ส.ส. บัญชีรายชื่อ พรรคแรงงาน ลำดับที่ 13[35][36]

หลังจากการลาออกจากตำแหน่งหัวหน้าพรรคของกอฟฟ์ เนื่องจากความพ่ายแพ้ของพรรคแรงงานในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2011 อาร์เดินได้สนับสนุนเดวิด เชียร์เรอร์ มากกว่าเดวิด คันลิฟฟ์ในการขึ้นมาดำรงหัวหน้าพรรคคนใหม่ และในวันที่ 19 ธันวาคม ค.ศ. 2011 ภายใต้การนำของเดวิด เชียร์เรอร์ หัวหน้าพรรคแรงงานคนใหม่ เธอก็ได้รับการเลื่อนตำแหน่งขึ้นมาเป็นรัฐมนตรีเงาอันดับสี่จากทั้งหมด 20 อันดับของคณะรัฐมนตรีเงา ในตำแหน่งรัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงพัฒนาสังคมเงา[33]

ในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2014 อาร์เดิร์นได้ลงเลือกตั้งในเขตออกแลนด์เซนทรัลอีกครั้ง เธอได้รับคะแนนเสียงเป็นอันดับสองรองจากเคย์เช่นเดียวกับครั้งที่ผ่านมา อย่างไรก็ตามครั้งนี้เธอได้รับคะแนนเสียงเพิ่มขึ้นเมื่อเทียบกับการเลือกตั้งครั้งก่อน และผลต่างระหว่างคะแนนเสียงที่โหวตให้เคย์และคะแนนเสียงที่โหวตให้อาร์เดิร์นลดลงจาก 717 เป็น 600 คะแนน[37] แม้จะแพ้ในการเลือกตั้งแบบแบ่งเขต แต่ในขณะเดียวกันอาร์เดิร์นอยู่ในอันดับที่ห้า ของลำดับผู้ลงสมัคร ส.ส. แบบบัญชีรายชื่อพรรคแรงงาน ทำให้เธอสามารถรักษาที่นั่งในสภาได้อีกสมัย สำหรับการทำงานในสภาครั้งนี้อาร์เดิร์นได้รับหน้าที่เป็นรัฐมนตรีเงากระทรวงยุติธรรม, กระทรวงเยาวชน, กระทรวงธุรกิจขนาดย่อม และกระทรวงศิลปะและวัฒนธรรม ภายใต้การนำของแอนดรูว์ ลิตเติล[38]

ใน ค.ศ. 2014 อาร์เดิร์นได้รับคัดเลือก และเข้าร่วมการประชุมผู้นำโลกรุ่นใหม่ (Forum of Young Global Leaders) ที่จัดขึ้น ณ ประเทศสวิตเซอร์แลนด์ โดยสภาเศรษฐกิจโลก (WEF)[39] หลังจากนั้นเธอก็ได้เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของประชาคมผู้นำโลกรุ่นใหม่ (Young Global Leaders Alumni Community)[40] และยังคงไปปาฐกถาในกิจกรรมที่จัดขึ้นโดย WEF อยู่บ่อยครั้ง

การเลือกตั้งซ่อมที่เมาท์อัลเบิร์ต[แก้]

อาร์เดิร์นำได้เสนอตัวเข้าเป็นผู้ท้าชิง ส.ส. ในการเลือกตั้งซ่อมเขตเมาท์อัลเบิร์ต ที่จะจัดขึ้นในเดือนกุมภาพันธ์ ค.ศ. 2017[41] ภายหลังจากการลาออกของเดวิด เชียร์เรอร์ในวันที่ 8 ธันวาคม ค.ศ. 2016 หลังจากปิดการให้เสนอตัวผู้ท้าชิงของพรรคแรงงานในวันที่ 12 มกราคม ค.ศ. 2017 อาร์เดิร์นเป็นเพียงคนเดียวที่ได้รับการเสนอชื่อและได้รับเลือกจากพรรคอย่างไรคู่แข่ง วันที่ 21 มกราคม ค.ศ. 2017 อาร์เดิร์นได้เข้าร่วมขบวนวีเมนส์มาร์ช การประท้วงที่จัดขึ้นทั่วโลก เพื่อต่อต้านดอนัลด์ ทรัมป์ ประธานาธิบดีคนใหม่ชองสหรัฐในขณะนั้น[42] และในวันถัดมา (22 มกราคม) พรรคแรงงานก็ได้ลงมติยืนยันว่าอาร์เดิร์นจะเป็นตัวแทนพรรคในการเลือกตั้งซ่อมที่จะจัดขึ้น[43][44] อาร์เดิร์นได้รับชัยชนะอย่างถล่มทลาย ได้รับคะแนนเสียงถึง 77 เปอร์เซ็นต์ในการเลือกตั้งดังกล่าว[45][46]

รองหัวหน้าพรรคแรงงาน[แก้]

หลังจากได้รับชัยชนะในการเลือกตั้งซ่อม อาร์เดิร์นได้รับการลงมติอย่างเป็นเอกฉันท์ให้ดำรงตำแหน่งรองหัวหน้าพรรคแรงงานในวันที่ 7 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 2017 หลังจากการลาออกของแอนเนตต์ คิง ผู้ซึ่งตั้งใจจะวางมือจากงานการเมืองในการเลือกตั้งครั้งถัดไป[47] ส่วนตำแหน่ง ส.ส. บัญชีรายชื่อที่เป็นที่นั่งเดิมของอาร์เดิร์น เรย์มอนด์ ฮัวได้เข้ามาดำรงตำแหน่งแทน[48]

ผู้นำฝ่ายค้าน[แก้]

1 สิงหาคม ค.ศ. 2017 เพียงเจ็ดสัปดาห์หลังจากการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2017 อาร์เดิร์นได้ขึ้นมาดำรงตำแหน่งหัวหน้าพรรคแรงงาน และตำแหน่งผู้นำฝ่ายค้านในลำดับถัดมา สืบเนื่องจากการลาออกของแอนดรูว์ ลิตเติล ที่ลาออกเพื่อแสดงความรับผิดชอบต่อผลคะแนนนิยมของพรรคที่ตกต่ำลงอย่างเป็นประวัติการณ์[49] ในที่ประชุมพรรคแรงงาน ในวันเดียวกันกับการลาออกของลิตเติล อาร์เดิร์นได้รับเลือกตั้งอย่างเป็นเอกฉันท์และไร้คู่แข่งให้ดำรงตำแหน่งหัวหน้าพรรคคนถัดไป[50] อาเดิร์นกลายเป็นหัวหน้าพรรคแรงงานนิวซีแลนด์ที่อายุน้อยที่สุดในประวัติศาสตร์ ด้วยอายุ 37 ปี[51] อีกทั้งเป็นหัวหน้าพรรคหญิงคนที่สองถัดจากเฮเลน คลาร์ก[52] อ้างจากคำบอกเล่าของอาร์เดิร์น ลิตเติลได้มาเข้ามาพบเธอก่อนหน้านั้น เมื่อ 26 กรกฎาคม ปีที่ผ่านมา เธอบอกว่าเขามีความคิดว่าเธอควรขึ้นมาเป็นหัวหน้าพรรคแรงงานแทนตัวเขา เนื่องจากเขามีความเห็นว่าเขาไม่สามารถพลิกฟื้นพรรคให้กลับมาดีขึ้นได้เลย ทว่าอาร์เดิร์นกลับปฎิเสธ และบอกเขาให้ "ทนต่อไปก่อน (Stick it out)"[53]

ในงานแถลงข่าวครั้งแรกหลังจากการขึ้นมาดำรงตำแหน่งหัวหน้าพรรคของเธอ เธอกล่าวว่าการรณรงค์หาเสียงเลือกตั้งที่กำลังจะมาถึงจะเป็นหนึ่งใน "ความเป็นไปในทิศทางที่ดีขึ้นอย่างไม่หยุดพัก (relentless positivity)"[18] ทันทีหลังจากการขึ้นดำรงตำแหน่ง พรรคแรงงานได้รับเงินบริจาคอย่างอย่างล้นหลาม ยอดสูงสุดถึง 700 ดอลลาร์นิวซีแลนด์ต่อนาที (ประมาณ 17,200 บาทต่อนาที)[54] และผลสำรวจคะแนนนิยมของพรรคแรงงานได้ทะยานขึ้นอย่างรวดเร็ว ในช่วงท้ายของเดือนสิงหาคม พรรคแรงงานได้รับคะแนนนิยมถึง 43 เปอร์เซ็นต์ ในการสำรวจของคอลมา บรุนตัน (จากเดิมที่ได้ 24 เปอร์เซ็นต์ในสมัยของหัวหน้าพรรคแอนดรูว์ ลิตเติล) อีกทั้งยังเป็นครั้งแรกในรอบทศวรรษที่พรรคแรงงานได้คะแนนนิยมมากกว่าพรรคแห่งชาติ[53] อย่างไรก็ตามกลุ่มคนที่ต่อต้านสังเกตว่าการทำงานของเธอคล้ายกับแอนดรูว์ ลิตเติลอย่างมาก แล้วบอกว่าการเพิ่มขึ้นของความนิยมต่อพรรคแรงงานอย่างฉับพลันนั้นมีเหตุผลจากความหนุ่มสาวและลักษณะหน้าตาที่ดูดีของเธอ[51]

ในกลางเดือนสิงหาคม อาร์เดิร์นได้ระบุว่ารัฐบาลพรรคแรงงานจะจัดตั้งหน่วยการทำงานศึกษาเกี่ยวกับภาษีเพื่อสำรวจความเป็นไปได้ในการในการเรียกเก็บภาษีเงินได้จากการขายหลักทรัพย์ และยกเลิกการเก็บภาษีบ้านและที่อยู่อาศัย[55][56] ภายหลังจากได้รับคำวิจารณ์ในแง่ลบอย่างกว้างขวาง อาร์เดิร์นตัดสินใจละทิ้งแผนการเรียกเก็บภาษีเงินได้จากการขายหลักทรัพย์ในระหว่างการเป็นรัฐบาลสมัยแรก[57][58] ต่อมา แกรนต์ โรเบิร์ตสัน โฆษกกระทรวงการคลังชี้แจ้งว่ารัฐบาลพรรคแรงงานจะไม่เสนอการเรียกเก็บภาษีใหม่ใด ๆ จนกว่าจะถึงการเลือกตั้งสมัยหน้า ค.ศ. 2020 การเปลี่ยนแปลงนโยบายเกิดขึ้นพร้อมกับข้อกล่าวหาที่รุนแรงจากสตีเวน จอยซ์ รัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงการคลัง เขากล่าวว่าพรรคแรงงานได้ "สูญเสีย" งบประมาณ 11.7 พันล้านดอลลาร์ไปกับการจัดทำนโยบายเกี่ยวกับภาษี[59][60]

ภาษีน้ำและมลพิษที่เสนอโดยพรรคแรงงานและพรรคกรีนยังก่อให้เกิดการวิพากษ์วิจารณ์จากเกษตรกร เมื่อวันที่ 18 กันยายน ค.ศ. 2017 กลุ่มสหพันธ์เกษตรกร (Federated Farmers) ได้จัดการประท้วงต่อต้านภาษีที่เมื่อมอร์รินส์วิลล์ บ้านเกิดของอาร์เดิร์น วินส์ตัน ปีเตอส์ หัวหน้าพรรคนิวซีแลนด์เฟิร์สได้เข้าร่วมการประท้วงดังกล่าว แต่ก็ถูกเกษตรกรตะโกนด่าทอว่าเขาเองมีความน่าสงสัยว่าเป็นหนึ่งในผู้สนับสนุนให้เกิดการเรียกเก็บภาษีนี้เช่นกัน ระหว่างการประท้วง มีเกษตรกรคนหนึ่งชูป้ายที่กล่าวหาอาร์เดิร์นว่าเป็น "นักคอมมิวนิสต์แสนสวย (Pretty communist)" เฮเลน คลาร์ก อดีตนายกรัฐมนตรีวิพากษ์วิจารณ์ว่าข้อความดังกล่าวแสดงความเกลียดชังต่อสตรี[61][62]

ในวันสุดท้ายของกำหนดการหาเสียง ผลต่างระหว่างคะแนนนิยมของทั้งสองพรรคลดน้อยลงโดยพรรคแห่งชาติกลับขึ้นมานำพรรคแรงงานเล็กน้อย[63]

การเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2017[แก้]

ระหว่างการเลือกตั้งทั่วเมื่อวันที่ 23 กันยายน ค.ศ. 2017 อาร์เดิร์นยังคงสามารถรักษาเก้าอี้ ส.ส. เขตเมาท์อัลเบิร์ต ชนะไปด้วยคะแนนเสียง 15,264 คะแนน[64][65][66] พรรคแรงงานมีส่วนแบ่งของคะแนนเพิ่มขึ้นเป็น 36.89 เปอร์เซ็น ขณะที่พรรคแห่งชาติมีส่วนแบ่งลดลงกลับลงมาที่ 44.45 เปอร์เซ็น พรรคแรงงานได้จำนวน ส.ส. เพิ่มขึ้น 14 ที่นั่ง รวมเป็นที่นั่งในสภาทั้งหมด 46 ที่นั่ง ซึ่งเป็นผลลัพธ์ที่ดีที่สุดสำหรับพรรคนับตั้งแต่สูญเสียอำนาจใน ค.ศ. 2008[67]

พรรคแห่งชาติ และพรรคฝ่ายตรงข้ามกับพรรคแรงงานไม่มีจำนวนที่นั่งมากพอที่จะจัดตั้งรัฐบาลได้ จึงได้มาเจรจากับพรรคกรีนและพรรคนิวซีแลนด์เฟิร์สเกี่ยวกับการจัดตั้งรัฐบาลผสม แต่อย่างไรก็ตามภายใต้ระบบการเลือกตั้งให้มีผู้แทนแบบจัดสรรปันส่วนผสม (MMP) พรรคนิวซีแลนด์อยู่ในตำแหน่งของผู้คุมดุลอำนาจได้ตัดสินใจเข้าร่วมการจัดตั้งรัฐบาลผสมกับพรรคแรงงาน[68][69]

การดำรงตำแหน่งนายกรัฐมนตรี (ค.ศ. 2017–ปัจจุบัน)[แก้]

สมัยที่หนึ่ง (ค.ศ. 2017–2020)[แก้]

เมื่อ 19 ตุลาคม ค.ศ. 2017 วินส์ตัน ปีเตอส์ หัวหน้าพรรคนิวซีแลนด์เฟิร์สตกลงเข้าร่วมจัดตั้งรัฐบาลผสมกับพรรคแรงงาน[6] ทำให้จาซินดา อาร์เดินกลายเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรีคนที่ 40 ของประเทศนิวซีแลนด์[70][71] การจัดตั้งรัฐบาลผสมครั้งนี้ได้รับความไว้วางใจและการสนับสนุนจากพรรคกรีน[72] อาร์เดิร์นแต่งตั้งให้ปีเตอร์เป็นรองนายกรัฐมนตรีและรัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงการต่างประเทศ แต่งตั้ง ส.ส. สามคนจากพรรคนิวซีแลนด์เฟิร์สให้ดำรงตำแหน่งรัฐมนตรี รวมที่นั่งในรัฐบาลที่เธอมอบโควตาให้แก่พรรคนิวซีแลนด์เฟิร์สเป็นห้าตำแหน่ง[73][74] ในวันถัดมา อาร์เดิร์นให้การยืนยันว่าเธอจะดำรงตำแหน่งรัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงความมั่งคงและข่าวกรองแห่งรัฐ, กระทรวงศิลปะ วัฒนธรรม และมรดกทางประวัติศาสตร์, และกระทรวงเด็กกลุ่มเปราะบาง (ซึ่งเป็นตำแหน่งเดียวกันกับช่วงที่เธอเป็นผู้นำฝ่ายค้านในคณะรัฐมนตรีเงาเมื่อรัฐบาลสมัยที่แล้ว[75]) ภายหลังในวาระของ ส.ส. เทรซีย์ มาร์ติน จากพรรคนิวซีแลนด์เฟิร์ส ตำแหน่งรัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงกิจการเด็กกลุ่มเปราะบางได้เปลี่ยนชื่อเป็นรัฐมนตรีว่าการกระทรวงการลดความยากจนในเด็ก[76] อาร์เดิร์นและคณะรัฐบาลได้เข้าพิธีสาบานตนเข้าดำรงตำแหน่งเมื่อวันที่ 26 ตุลาคม ค.ศ. 2017 โดยมีเดมแพตซี เรดดีเป็นผู้สำเร็จราชการ[77] เมื่อเข้ารับตำแหน่ง อาร์เดิร์นกล่าวว่ารัฐบาลของเธอจะ "มุ่งมั่น, เห็นอกเห็นใจ และเข้มแข็ง (focused, empathetic and strong)"[78]

อาร์เดิร์นเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรีหญิงคนที่สามของประเทศถัดจากเจนนี ชิปลีย์ (ค.ศ. 1997–1999) และเฮเลน คลาร์ก (ค.ศ. 1999–2008)[79][80] เธอเป็นสมาชิกของสภาผู้นำสตรีโลก[81] ด้วยอายุ 37 ปี อาร์เดิร์นกลายเป็นหัวหน้ารัฐบาลนิวซีแลนด์ที่มีอายุน้อยที่สุดนับตั้งแต่สมัยของเอ็ดเวิร์ด สแตฟฟอร์ด (ดำรงตำแหน่งนายกรัฐมนตรีคนที่สามของนิวซีแลนด์เมื่อ ค.ศ. 1856)[82] เมื่อวันที่ 19 มกราคม ค.ศ. 2018 อาร์เดิร์นประกาศว่าเธอกำลังตั้งครรภ์ และมอบหมายให้วินส์ตัน ปีเตอส์รักษาราชการแทนเป็นเวลาหกสัปดาห์[83] ในช่วงที่เธอลาคลอดตั้งแต่ 21 มิถุนายน ถึง 2 สิงหาคม ค.ศ. 2018[84][85][86]

กิจการภายในประเทศ[แก้]

อาร์เดิร์นสัญญาว่าจะลดปัญหาความยากจนในเด็กของประเทศลงครึ่งหนึ่งภายใน 10 ปี[87] ในเดือนกรกฎาคม ค.ศ. 2018 อาร์เดิร์นประกาศการเริ่มการดำเนินการ "แพ็กเกจสำหรับครอบครัว (Families Package)"[88] ซึ่งเป็นนโยบายเรือธงของรัฐบาล แพ็กเกจดังกล่าวค่อย ๆ เพิ่มวันลาเพื่อเลี้ยงดูบุตรเป็น 26 สัปดาห์ และเสนอการจัดสรรรายได้ถ้วนหน้า 60 ดอลลาร์ต่อสัปดาห์ (BestStart Payment) แก่ครอบครัวรายได้ต่ำถึงปานกลางที่มีเด็กเล็ก การชดเชยภาษีแก่ครอบครัว, สวัสดิการเด็กกำพร้า, เงินช่วยเหลือค่าที่อยู่อาศัย และเบี้ยงเลี้ยงเพื่อการเลี้ยงดูบุตรได้มีการปรับเพิ่มขึ้นอย่างมากเช่นกัน[89] ใน ค.ศ. 2019 รัฐบาลได้เริ่มนำร่องโครงการอาหารกลางวันในโรงเรียนเพื่อสนับสนุนการลดจำนวนเด็กยากจนลง จากนั้นจึงขยายผลออกไปในโรงเรียนด้อยโอกาสทั่วประเทศ ช่วยเหลือเด็กกว่า 200,000 คน (ประมาณร้อยละ 25 ของจำนวนนักเรียนในสารบบ)[90] และยังมีความพยายามในการลดความยากจนในแนวทางอื่น ๆ ที่รวมไปถึงการเพิ่มสวัสดิการหลักต่าง ๆ[91] ขยายจำนวนครั้งในการเข้าพบแพทย์โดยไม่มีค่าใช้จ่าย, แจกจ่ายผลิตภัณฑ์สุขอนามัยสำหรับผู้มีประจำเดือนฟรีในโรงเรียน[92] และเพิ่มจำนวนที่อยู่อาศัยที่จัดสรรโดยรัฐ[93]

อย่างไรก็ตาม ใน ค.ศ. 2022 นักวิจารณ์กล่าวว่าราคาที่อยู่อาศัยที่เพิ่มสูงขึ้นอย่างต่อเนื่องกำลังสร้างผลกระทบอย่างหนักต่อภาคครัวเรือน เปรียบเสมือนทำให้ครอบครัวที่ต้องแบกรับภาระดังกล่าวพิการ และจำเป็นต้องมีการเปลี่ยนแปลงอย่างเป็นระบบเพื่อให้ผลลัพธ์ในการแก้ไขปัญหาคงอยู่อย่างยั่งยืน[94]

ในด้านเศรษฐกิจ รัฐบาลของอาร์เดิร์นได้ดำเนินการปรับขึ้นค่าแรงขั้นต่ำของประเทศอย่างต่อเนื่อง[95] และได้เสนอกองทุนเพื่อการเติบโตส่วนภูมิภาค (Provincial Growth Fund) เพื่อลงทุนในโครงการพัฒนาโครงสร้างพื้นฐานในเขตชนบท[96] มีการยกเลิกแผนลดภาษีของพรรคแห่งชาติ โดยกล่าวว่ารัฐบาลจะจัดลำดับความสำคัญของรายจ่ายด้านการสาธารณสุขและการศึกษาเป็นการทดแทน[97] การขยายการให้เรียนฟรีไปจนถึงปีแรกของการศึกษาในระดับที่สูงกว่ามัธยมศึกษา โดยเปิดให้เรียนฟรีตั้งแต่วันที่ 1 มกราคม ค.ศ. 2018 เป็นต้นไป หลังจากการดำเนินนโยบายด้านอุตสาหกรรม ใน ค.ศ. 2021 รัฐบาลตกลงที่จะเพิ่มค่าจ้างครูระดับประถมศึกษาขึ้นร้อยละ 12.8 (สำหรับครูในช่วงต้นของการทำงาน) และร้อยละ 18.5 (สำหรับครูอาวุโสที่ไม่มีตำแหน่งรับผิดชอบอื่นใด)[98]

แม้ว่าในการหาเสียงเลือกตั้งตลอดสามครั้งที่ผ่านมาพรรคแรงงานจะรณรงค์ให้มีการเรียกเก็บภาษีเงินได้จากการขายหลักทรัพย์ อาร์เดิร์นให้คำมั่นเมื่อเดือนเมษายน ค.ศ. 2019 ว่ารัฐบาลย์ภายใต้การนำของเธอจะไม่มีการเก็บภาษีเงินได้จากการขายหลักทรัพย์[99][100] อย่างไรก็ตามตั้งแต่นั้นมาได้มีปรับการเก็บภาษีเงินได้จากการขายอสังหาริมทรัพย์จากที่จากเดิมต้องมีระยะเวลาการถือครองน้อยกว่าห้าปีขยายเพิ่มเป็นสิบปี[101]

Ardern เดินทางไปยัง Waitangi ในปี 2018 เพื่อเฉลิมฉลองวัน Waitangi ประจำปี อยู่ใน Waitangi เป็นเวลาห้าวันยาวนานอย่างที่ไม่เคยมีมาก่อน อาร์เดิร์นกลายเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรีหญิงคนแรกที่พูดจากผู้นำสูงสุด การมาเยี่ยมของเธอได้รับการตอบรับเป็นอย่างดีจากผู้นำชาวเมารี โดยนักวิจารณ์สังเกตเห็นความแตกต่างอย่างมากกับคำตอบที่รุนแรงซึ่งได้รับจากรุ่นก่อนของเธอหลายคน

เมื่อวันที่ 24 สิงหาคม พ.ศ. 2561 อาร์เดิร์นถอดแคลร์ เคอร์แรน รัฐมนตรีกิจการกระจายเสียงและแพร่ภาพกระจายเสียงออกจากคณะรัฐมนตรี หลังจากที่เธอล้มเหลวในการเปิดเผยการประชุมกับผู้ประกาศข่าวนอกธุรกิจของรัฐสภา ซึ่งถูกตัดสินว่ามีความขัดแย้งทางผลประโยชน์ Curran ยังคงเป็นรัฐมนตรีนอกคณะรัฐมนตรี และ Ardern ถูกวิพากษ์วิจารณ์จากฝ่ายค้านที่ไม่ยอมไล่ Curran ออกจากผลงานของเธอ ต่อมาอาร์เดิร์นยอมรับการลาออกของเคอร์แรน ในปี 2019 เธอถูกวิพากษ์วิจารณ์ว่าเป็นเพราะเธอจัดการกับข้อกล่าวหาเรื่องการล่วงละเมิดทางเพศกับเจ้าหน้าที่พรรคแรงงาน Ardern กล่าวว่าเธอได้รับแจ้งว่าข้อกล่าวหาไม่เกี่ยวข้องกับการล่วงละเมิดทางเพศหรือความรุนแรงก่อนที่จะมีการเผยแพร่รายงานเกี่ยวกับเหตุการณ์ดังกล่าวใน The Spinoff สื่อตั้งคำถามกับบัญชีของเธอ โดยมีนักข่าวคนหนึ่งระบุว่าอาร์เดิร์นอ้างว่าการฟ้องร้องดังกล่าวเป็นเรื่องที่ "ยากที่จะยอมรับ (hard to swallow)"

Ardern travelled to Waitangi in 2018 for the annual Waitangi Day commemoration; stayed in Waitangi for five days, an unprecedented length.[102] Ardern became the first female prime minister to speak from the top marae. Her visit was largely well received by Māori leaders, with commentators noting a sharp contrast with the acrimonious responses received by several of her predecessors.[102][103]

On 24 August 2018, Ardern removed Broadcasting Minister Clare Curran from Cabinet after she failed to disclose a meeting with a broadcaster outside of parliamentary business, which was judged to be a conflict of interest. Curran remained a minister outside Cabinet, and Ardern was criticised by the Opposition for not dismissing Curran from her portfolio. Ardern later accepted Curran's resignation.[104][105] In 2019, she was criticised for her handling of an allegation of sexual assault against a Labour Party staffer. Ardern said she had been told the allegation did not involve sexual assault or violence before a report about the incident was published in The Spinoff.[106] Media questioned her account, with one journalist stating that Ardern's claim was "hard to swallow".[107][108]

อาร์เดิร์นต่อต้านการดำเนินคดีกับผู้ใช้กัญชาในนิวซีแลนด์ และรับปากว่าจะจัดการลงประชามติในประเด็นนี้[109] การออกเสียงประชามติอย่างไม่มีผลผูกพันเกี่ยวกับกัญชาถูกกฏหมายได้จัดขึ้นร่วมกับลงคะแนนเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2020 เมื่อวันที่ 17 ตุลาคม ค.ศ. 2020 อาเดิร์นยอมรับว่าเธอจะโหวตผ่านกฎหมายกัญชาในระหว่างการโต้วาทีที่ถ่ายทอดสดก่อนการเลือกตั้งที่จะมาถึง[110] ผลการลงประชามติออกมาด้วยผลไม่ยอมรับร่างพระราชบัญญัติการควบคุมและทำให้กัญชาถูกกฎหมาย ด้วยคะแนนเสียงไม่เห็นด้วย 51.17 เปอร์เซ็นต์[111] การศึกษาย้อนหลังที่ตีพิมพ์ในวารสารทางการแพทย์ให้ความเห็นว่าการที่อาร์เดิร์นปฏิเสธที่จะรณรงค์โหวตเห็นด้วยอย่างชัดเจน "อาจจะเป็นปัจจัยชี้ขาดที่ทำให้ผลประชามติออกมาพ่ายแพ้ไปอย่างฉิวเฉียด"[112]

กิจการระหว่างประเทศ[แก้]

On 5 November 2017, Ardern made her first official overseas trip to Australia, where she met Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull for the first time. Relations between the two countries had been strained in the preceding months because of Australia's treatment of New Zealanders living in the country, and shortly before taking office, Ardern had spoken of the need to rectify this situation, and to develop a better working relationship with the Australian government.[113] Turnbull described the meeting in cordial terms: "we trust each other...The fact we are from different political traditions is irrelevant".[114] In 2020, Ardern criticised Australia's policy of deporting New Zealanders, many of whom had lived in Australia but had not taken up Australian citizenship, as "corrosive" and damaging to Australia–New Zealand relations.[115][116][117]

Ardern attended the 2017 APEC summit in Vietnam,[118] the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 2018 in London (featuring a private audience with Queen Elizabeth II)[119] and a United Nations summit in New York City. After her first formal meeting with Donald Trump she reported that the US president showed "interest" in New Zealand's gun buyback scheme.[120][121] In 2018, Ardern raised the issue of Xinjiang re-education camps and human rights abuses against the Uyghur Muslim minority in China.[122][123] Ardern has also raised concerns over the persecution of the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.[124]

Ardern travelled to Nauru, where she attended the 2018 Pacific Islands Forum. Media and political opponents criticised her decision to travel separately from the rest of her contingent, costing taxpayers up to NZ$100 000, so that she could spend more time with her daughter.[125] At a 2018 United Nations General Assembly meeting, Ardern became the first female head of government to attend with her infant present.[126][127] Her address to the General Assembly praised the United Nations for its multilateralism, expressed support for the world's youth, called for immediate attention to the effects and causes of climate change, for the equality of women, and for kindness as the basis for action.[128]

Trade and Export Growth Minister David Parker and Ardern announced that the government would continue participating in the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations despite opposition from the Green Party.[129] New Zealand ratified the revised agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership,[130] which she described as being better than the original TPP agreement.[131]

เหตุกราดยิงมัสยิดในไครสต์เชิร์ช[แก้]

On 15 March 2019, 51 people were fatally shot and 49 injured in two mosques in Christchurch. In a statement broadcast on television, Ardern offered condolences and stated that the shootings had been carried out by suspects with "extremist views" that have no place in New Zealand, or anywhere else in the world.[134] She also described it as a well-planned terrorist attack.[135]

Announcing a period of national mourning, Ardern was the first signatory of a national condolence book that she opened in the capital, Wellington.[136] She also travelled to Christchurch to meet first responders and families of the victims.[137] In an address at the Parliament, she declared she would never say the name of the attacker: "Speak the names of those who were lost rather than the name of the man who took them ... he will, when I speak, be nameless."[138] Ardern received international praise for her response to the shootings,[139][140][141][142] and a photograph of her hugging a member of the Christchurch Muslim community with the word "peace" in English and Arabic was projected onto the Burj Khalifa, the world's tallest building.[143] A 25-เมตร (82-ฟุต) mural of this photograph was unveiled in May 2019.[144]

In response to the shootings, Ardern announced her government's intention to introduce stronger firearms regulations.[145] She said that the attack had exposed a range of weaknesses in New Zealand's gun law.[146] Less than one month after the attack, the New Zealand Parliament passed a law that bans most semiautomatic weapons and assault rifles, parts that convert guns into semiautomatic guns, and higher capacity magazines.[147] Ardern and French President Emmanuel Macron co-chaired the 2019 Christchurch Call summit, which aimed to "bring together countries and tech companies in an attempt to bring to an end the ability to use social media to organise and promote terrorism and violent extremism".[148]

การระบาดของโควิด-19[แก้]

On 14 March 2020, Ardern announced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand that the government would be requiring anyone entering the country from midnight 15 March to isolate themselves for 14 days.[149] She said the new rules will mean New Zealand has the "widest ranging and toughest border restrictions of any country in the world".[150] On 19 March, Ardern stated that New Zealand's borders would be closed to all non-citizens and non-permanent residents, after 11:59 pm on 20 March (NZDT).[151] Ardern announced that New Zealand would move to alert level 4, including a nationwide lockdown, at 11:59 pm on 25 March.[152]

National and international media covered the government response led by Ardern, praising her leadership and swift response to the outbreak in New Zealand.[153][154] The Washington Postแม่แบบ:'s Fifield described her regular use of interviews, press conferences and social media as a "masterclass in crisis communication."[155] Alastair Campbell, a journalist and adviser in Tony Blair's British government, commended Ardern for addressing both the human and economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic.[156]

In mid-April 2020, two applicants filed a lawsuit at the Auckland High Court against Ardern and several government officials including Director-General of Health Ashley Bloomfield, claiming that the lockdown imposed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic infringed on their freedoms and was made for "political gain". The lawsuit was dismissed by Justice Mary Peters of the Auckland High Court.[157][158]

On 5 May 2020, Ardern, her Australian counterpart Scott Morrison and several Australian state and territorial leaders agreed that they would collaborate to develop a trans-Tasman COVID-safe travel zone that would allow residents from both countries to travel freely without travel restrictions as part of efforts to ease coronavirus restrictions.[159][160]

Post-lockdown opinion polls showed the Labour Party with nearly 60 per cent support.[161][162] In May 2020, Ardern rated 59.5 per cent as 'preferred prime minister' in a Newshub-Reid Research poll—the highest score for any leader in the Reid Research poll's history.[163][164] By January 2022, that figure had slumped to 35 per cent.[165]

สมัยที่สอง (ตั้งแต่ ค.ศ. 2020)[แก้]

ในการเลือกตั้งทั่วไป ค.ศ. 2020 อาร์เดิร์นได้นำพรรคแรงงานคว้าชัยชนะอย่างถล่มทลาย[166] ด้วยจำนวน ส.ส. เสียงข้างมากในสภารวม 65 ที่นั่ง จากทั้งหมด 120 ที่นั่งของสภาผู้แทนราษฎร และได้รับคะแนนโหวตพรรค (Party vote) ถึง 50% ของจำนวนผู้มาใช้สิทธิเลือกตั้ง[167] และอาร์เดิร์นก็ยังสามารถรักษาชัยชนะในเขตเลือกตั้งเมาท์อัลเบิร์ตด้วยคะแนนมากกว่าคู่แข่งอันดับสองถึง 21,246 คะแนน[168][169] อาร์เดิร์นระบุว่าชัยชนะในครั้งนี้เกิดจากผลงานของรัฐบาลในการจัดกับวิกฤตการระบาดของโควิด-19 และผลต่อเนื่องทางเศรษฐกิจในช่วงเวลาดังกล่าว[170]

กิจการภายในประเทศ[แก้]

On 2 December 2020, อาร์เดิร์นได้ประกาศสถานการณ์ฉุกเฉิน เรื่อง ปัญหาเปลี่ยนแปลงของสภาพภูมิอากาศในนิวซีแลนด์ and pledged that the Government would be carbon neutral by 2025 in a parliamentary motion. As part of this commitment towards carbon neutrality, the public sector will be required to buy only electric or hybrid vehicles, the fleet will be reduced over time by 20 per cent, and all 200 coal-fired boilers in public service buildings will be phased out. This motion was supported by the Labour, Green, and Māori parties but was opposed by the opposition National and ACT parties.[171][172] However, climate activist Greta Thunberg said about Jacinda Ardern: "It's funny that people believe Jacinda Ardern and people like that are climate leaders. That just tells you how little people know about the climate crisis ... the emissions haven't fallen."[173]

In response to worsening housing affordability issues, Minister of Housing and Urban Development, Megan Woods, announced new reforms. These reforms included the removal of the interest rate tax-deduction, lifting Housing Aid for first home buyers, renewed allocation of infrastructure funds (named Housing Acceleration Fund) for district councils, an extension of the Bright Line Test from five to ten years.[174][175]

On 14 June 2021, Ardern confirmed that the New Zealand Government would formally apologise for the Dawn Raids at the Auckland Town Hall on 26 June 2021. The Dawn Raids were a series of police raids which disproportionately targeted members of the Pasifika diaspora in New Zealand during the 1970s and early 1980s.[176][177]

โควิด-19 และแผนการฉีดวัคซีน[แก้]

On 17 June 2020, Prime Minister Ardern met with Bill Gates and Melinda Gates via a teleconference in a meeting requested by Bill Gates. In the meeting, Ardern was asked by Melinda Gates to "speak up" in support of a collective approach to a Covid-19 vaccine. Ardern said she'd be happy to assist, an Official Information Act request response has shown. A month earlier in May, Ardern's Government had pledged $37 million to help find a COVID-19 vaccine, which included $15 million to CEPI (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) founded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the World Economic Forum among others, and $7 million to GAVI (Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation), also founded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. During the meeting Gates noted this contribution.[178] Ardern had also met the Gates' the year before in New York.[179]

On 12 December 2020, Ardern and Cook Islands prime minister Mark Brown announced that a travel bubble between New Zealand and the Cook Islands would be established in 2021, allowing two-way quarantine-free travel between the two countries.[180] On 14 December, Prime Minister Ardern confirmed that the New Zealand and Australian Governments had agreed to establish a travel bubble between the two countries the following year.[181] On 17 December, Ardern also announced that the Government had purchased two more vaccines from the pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca and Novavax for New Zealand and its Pacific partners in addition to the existing stocks from Pfizer/BioNTech and Janssen Pharmaceutica.[182]

On 26 January 2021, Ardern stated that New Zealand's borders would remain closed to most non-citizens and non-residents until New Zealand citizens have been "vaccinated and protected".[183] The COVID-19 vaccination programme began in February 2021.[184] An outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in August 2021 prompted the government to enact a nationwide lockdown again.[185] By September, the number of new community infections began to fall again; comparisons were made with an outbreak in neighbouring Australia, which was unable to contain a Delta variant outbreak at the same time.[186]

On 29 January 2022, Ardern entered into self-isolation after she was identified as a close contact of a COVID-19 case on an Air New Zealand flight from Kerikeri to Auckland on 22 January. In addition Goveror-General Cindy Kiro and chief press secretary Andrew Campbell, who were aboard the same flight, also went into self-isolation.[187]

ความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างประเทศ[แก้]

In early December 2020, Ardern expressed support for Australia during a dispute between Canberra and Beijing over Chinese Foreign Ministry official Zhao Lijian's Twitter post alleging that Australia had committed war crimes against Afghans. She described the image as not being factual and incorrect, adding that the New Zealand Government would raise its concerns with the Chinese Government.[188] [189]

On 9 December 2020, Ardern delivered a speech virtually at the Singapore FinTech Festival, applauding the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) among New Zealand, Chile and Singapore as “the first important steps” to achieve the regulatory alignment to facilitate businesses.[190]

On 16 February 2021, Ardern criticised the Australian Government's decision to revoke dual New Zealand–Australian national and ISIS bride Suhayra Aden's Australian citizenship. Aden had migrated from New Zealand to Australia at the age of six and acquired Australian citizenship. She subsequently travelled to Syria to live in the Islamic State in 2014. On 15 February 2021, Aden and two of her children were detained by Turkish authorities for illegal entry. Ardern accused the Australian Government of abandoning its obligations to its citizens and also offered consular support to Aden and her children. In response, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison defended the decision to revoke Aden's citizenship, citing legislation stripping dual nationals of their Australian citizenship if they were engaged in terrorist activities.[191][192][193] Following a phone conversation, the two leaders agreed to work together to address what Ardern described as "quite a complex legal situation."[194]

In response to the 2021 Israel–Palestine crisis, Ardern stated on 17 May that New Zealand "condemned both the indiscriminate rocket fire we have seen from Hamas and what looks to be a response that has gone well beyond self-defence on both sides." She also stated that Israel had the "right to exist" but Palestinians also had a "right to a peaceful home, a secure home."[195]

In late May 2021, Ardern hosted Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison during a state visit at Queenstown. The two heads of governments issued a joint statement affirming bilateral cooperation on the issues of COVID-19, bilateral relations, and security issues in the Indo-Pacific. Ardern and Morrison also raised concerns about the South China Sea dispute and human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang.[196][197] In response to the joint statement, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin criticised the Australian and New Zealand governments for interfering in Chinese domestic affairs.[198]

In early December 2021, Ardern participated in the virtual Summit for Democracy that was hosted by United States President Joe Biden. In her address, she talked about bolstering democratic resilience in the age of COVID-19 followed by panel discussions. Ardern also announced that New Zealand would contribute an additional NZ$1 million to supporting Pacific countries' anti-corruption efforts, as well as contributing to UNESCO's Global Media Defence Fund and the International Fund for Public Interest Media.[199]

มุมมองทางการเมือง[แก้]

อาร์เดิร์นนิยามตนเองว่ามีอุดมการณ์แบบประชาธิปไตยสังคมนิยม[9], พิพัฒนาการนิยม[10], สาธารณรัฐนิยม[200] และสตรีนิยม[201] เธอยกย่องเฮเลน คลาร์กว่าเป็นวีรสตรีทางการเมือง[9][202] เธอบอกว่าการเพิ่มขึ้นของปัญหาความยากจนในเด็ก ปัญหาการไม่มีที่อยู่อาศัยและคนไร้บ้านเป็น "ความล้มเหลวที่โจ่งแจ้งและไร้ยางอาย" ของระบบทุนนิยม[203][204] เธอกล่าวว่า: "ฉันระบุว่าตัวฉันเป็นประชาธิปไตยสังคมนิยมมาโดยตลอด" ในระหว่างการตอบคำถามสื่อมวลชนเกี่ยวกับงบประมาณแผ่นดิน ค.ศ. 2021 อย่างไรก็ตามการประกาศตนว่ามีอุดมการณ์แบบประชาธิปไตยสังคมนิยมก็ไม่ได้สร้างผลประโยชน์อะไรมาก เนื่องจากเป็นคำที่ไม่ได้นิยมกล่าวกันโดยทั่วไปในภูมิทัศน์ทางการเมืองของนิวซีแลนด์[205] อาเดิร์นสนับสนุนการลดลงของอัตราการนำเข้าผู้อพยพ โดยคาดหวังให้เพดานการรับผู้อพยพลดลงเหลือราวปีละ 20,000–30,000 คน เธอให้เหตุผลว่า "ความตั้งใจในการแก้ไขปัญหาภาวะขาดแคลนแรงงานทักษะสูงของเรายังดำเนินไปในทิศทางที่ไม่ถูกต้อง และยังไม่มีแผนรองรับการเจริญเติบโตของประชากรที่เพียงพอ" และ "จะมีปัญหาต่อสาธารณูปโภคขั้นพื้นฐาน"[206] อย่างไรก็ตาม เธอต้องการเพิ่มจำนวนการรับผู้ลี้ภัย[207]

อาร์เดิร์นเชื่อว่าการจะยุบหรือคงไว้ซึ่งเขตเลือกตั้งพิเศษสำหรับชาวมาวรี (Māori electorates) ควรจะได้รับการตัดสินจากชาวมาวรี เธอกล่าวว่า "ถ้า[ชาวมาวรี]ยังไม่ได้มีการเรียกร้องให้ยกเลิกที่นั่งเหล่านี้ไป แล้วทำไมเราต้องยกประเด็นขึ้นมา"[208] เธอสนับสนุนให้โรงเรียนในนิวซีแลนด์สอนวิชาภาษามาวรีเป็นวิชาบังคับ[9]

ในกันยายน ค.ศ. 2017 อาร์เดิร์นบอกว่าเธอต้องการให้นิวซีแลนด์มีการจัดการอภิปรายเกี่ยวกับการถอดถอนพระมหากษัตริย์แห่งนิวซีแลนด์ออกจากตำแหน่งประมุขแห่งรัฐ[200] ระหว่างการอ่านคำแถลงการณ์ในพิธีแต่งตั้งเดม ซินดี คิโร เป็นผู้สำเร็จราชการนิวซีแลนด์ อาร์เดิร์นบอกว่าเธอเชื่อว่านิวซีแลนด์จะกลายเป็นสาธารณรัฐในช่วงชีวิตของเธอนี้[209] เธอได้เข้าพบกับพระบรมวงศานุวงษ์อยู่บ่อยครั้งในตลอดระยะเวลาหลายปี เธอกล่าวว่า "ทัศนะทางการเมืองของฉันไม่ได้มีผลที่จะเปลี่ยนแปลงความเคารพที่ฉันมีต่อพระบาทสมเด็จพระราชินีและพระบรมวงศานุวงษ์ และต่อคุณูปการที่ที่ราชวงศ์ได้ทรงทำไว้ให้กับประเทศนิวซีแลนด์ ฉันคิดว่าเราสามารถมีมุมมองทั้งสองอย่างไปพร้อมกันได้ (ทั้งการนำประเทศสู่สาธารณรัฐ และความเคารพต่อราชวงษ์) และนี่คือสิ่งฉันคิด"[210]

อาร์เดิร์นได้อภิปรายสนับสนุนการสมรสเพศเดียวกัน[211] และโหวตสนับสนุนพระราชบัญญัติแก้ไขเพิ่มเติมการสมรส (นิยามการสมรส) ค.ศ. 2013 ซึ่งเป็นกฎหมายที่ทำให้การสมรสระหว่างเพศเดียวกันนั้นสามารถทำได้ถูกต้องตามกฎหมาย[212] ใน ค.ศ. 2018 เธอกลายเป็นนายรัฐมนตรีนิวซีแลนด์คนแรกที่เข้าร่วมไพรด์พาเรด[213] อาร์เดิร์นสนับสนุนให้ลบการทำแท้งออกจากการเป็นความผิดอาญาในพระราชบัญญัติประมวลกฎหมายอาญา ค.ศ. 1961[214][215] ต่อมาในเดือนมีนาคม ค.ศ. 2020 เธอได้ลงคะแนนเสียงเห็นชอบพระราชบัญญัติการทำแท้ง กฎหมายที่บัญญัติให้การทำแท้งปราศจากความผิดทางอาญาเมื่อเป็นการร้องขอจากผู้ตั้งครรภ์[216][217]

อาเดิร์นกล่าวถึงนโยบายเขตปลอดนิวเคลียร์ของนิวซีแลนด์ ว่าปฏิบัติการแก้ไขปัญหาการเปลี่ยนแปลงของสภาพภูมิอากาศ เป็นเสมือนกับปฏิบัติการแก้ไขปัญหานิวเคลียร์ในรุ่นของเธอ ("Climate change is my generation's nuclear-free moment")[218]

อาร์เดิร์นได้กล่าวสนับสนุนทางออกสองรัฐเพื่อคลี่คลายปัญหาความขัดแย้งอิสราเอล–ปาเลสไตน์[219] เธอได้ประณามอิสราเอลในการสังหารชาวปาเลสไตน์ที่ออกมาชุมนุมประท้วงที่ชายแดนกาซา[220]

อาร์เดิร์นโหวตสนับสนุนการทำให้กัญชาถูกต้องตามกฎหมายในการทำประชามติเกี่ยวกับกัญชาใน ค.ศ. 2020 อย่างไรก็ตามเธอหลีกเลี่ยงที่จะเปิดเผยจุดยืนของเธอ จนกระทั่งผลการลงประชามติเสร็จสิ้น[221]

ภาพลักษณ์ในที่สาธารณะ[แก้]

After becoming the Labour Party leader, Ardern received positive coverage from many sections of the media, including international outlets such as CNN,[222] with commentators referring to a 'Jacinda effect' and 'Jacindamania'.[223][224]

Jacindamania was cited as a factor behind New Zealand gaining global attention and media influence in some reports, including the Soft Power 30 index.[225] In a 2018 overseas trip, Ardern attracted much attention from international media, particularly after delivering a speech at the United Nations in New York. She contrasted with contemporary world leaders, being cast as an "antidote to Trumpism".[226] Writing for Stuff, Tracy Watkins said Ardern made a "cut-through on the world stage" and her reception was as a "... torch carrier for progressive politics as a young woman who breaks the mold in a world where the political strongman is on the rise. She is a foil to the muscular diplomacy of the likes of US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin."[227]

Ardern has been described as a celebrity politician.[228][229][230]

A year after Ardern forming her government, The Guardian's Eleanor Ainge Roy reported that Jacindamania was waning in the population, with not enough of the promised change visible.[231] When Toby Manhire, the editor of The Spinoff, reviewed the decade in December 2019, he praised Ardern for her leadership following the Christchurch mosque shootings and the Whakaari / White Island eruption:

| “ | Ardern ... revealed an empathy, steel and clarity that in the most appalling circumstances brought New Zealanders together and inspired people the world over. It was a strength of character that showed itself again this week following the tragic eruption at Whakaari.[232] | ” |

รางวัล และเกียรติยศ[แก้]

อาร์เดิร์นเป็นหนึ่งใน 15 คนที่ได้รับเลือกให้ไปปรากฏบนหน้าปกของนิตยสารบริติชโวค ฉบับเดือนกันยายน ค.ศ. 2019 โดยมีเมแกน ดัชเชสแห่งซัสเซกซ์เป็นบรรณาธิดารับเชิญของฉบับนั้น

นิตยสารฟอบส์ได้จัดให้อาร์เดิร์นอยู่ในอันดับที่ 34 ใน 100 อันดับผู้หญิงที่ทรงอิทธิพลที่สุดในโลก ประจำ ค.ศ. 2021

Ardern was one of fifteen women selected to appear on the cover of the September 2019 issue of British Vogue, by guest editor Meghan, Duchess of Sussex.[233] Forbes magazine has consistently ranked her among the 100 most powerful women in the world, placed 34 in 2021.[234] She was included in the 2019 Time 100 list[235] and shortlisted for Time's 2019 Person of the Year.[236] The magazine later incorrectly speculated that she might win the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize among a listed six candidates, for her handling of the Christchurch mosque shootings.[237] In 2020, she was listed by Prospect as the second-greatest thinker for the COVID-19 era.[238] On 19 November 2020, Ardern was awarded Harvard University's 2020 Gleitsman International Activist Award; she contributed the US$150,000 (NZ$216,000) prize money to New Zealanders studying at the university.[239]

In 2021, New Zealand zoologist Steven A. Trewick named the flightless wētā species Hemiandrus jacinda in honour of Ardern.[240] A spokesperson for Ardern said[241] that a beetle (Mecodema jacinda), a lichen (Ocellularia jacinda-arderniae),[242] and an ant (Crematogaster jacindae, found in Saudi Arabia)[243] had also been named after her.

In mid-May 2021, Fortune magazine gave Ardern the top spot on their list of world's greatest leaders, citing her leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as her handling of the Christchurch mosque shootings and the 2019 Whakaari/White Island eruption.[244][245]

ชีวิตส่วนตัว[แก้]

มุมมองทางศาสนา[แก้]

ในวัยเด็กเธอนับถือศาสนาคริสต์ในศาสนจักรของพระเยซูคริสต์แห่งวิสุทธิชนยุคสุดท้าย (ศาสนจักรแอลดีเอส) แต่เมื่ออาร์เดิร์นอายุได้ 25 ปี เธอก็หันหลังให้กับคริสต์ศาสนา เพราะเธอมองว่าศาสนจักรมีมุมมองความเชื่อที่ขัดแย้งกับเธอ โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในเรื่องของการสนับสนุนสิทธิและการเคลื่อนไหวของกลุ่มบุคคลที่มีความหลากหลายทางเพศ[246][247] ในมกราคม ค.ศ. 2017 อาร์เดิร์นระบุว่าเธอเป็นอไญยนิยม (กลุ่มบุคคลที่บอกว่าปัญญาของมนุษย์นั้นไปไม่อาจจะสามารถตัดสินได้ว่า พระเจ้ามีอยู่จริง หรือไม่มีอยู่จริง) เธอกล่าวว่า[246]

"I can't see myself being a member of an organised religion again" แปล: "ฉันมองไม่เห็นโอกาสที่ตัวฉันจะกลับไปเป็นศาสนิกชนขององค์กรทางศาสนาใด ๆ ได้อีกครั้ง"

ในฐานะนายกรัฐมนตรีนิวซีแลนด์ ค.ศ. 2019 เธอได้เข้าพบกับรัสเซลล์ เอ็ม. เนลสัน ผู้นำศาสนาจักรแอลดีเอส[248]

ครอบครัว[แก้]

อาร์เดิร์นเป็นลูกพี่ลูกน้องคนที่สองของแฮมิช แมคโดอัลล์ นายกเทศมนตรีของวางกานูอี[249] เธอเป็นญาติห่าง ๆ ของเชน อาร์เดิร์น อดีต ส.ส. พรรคแห่งชาติ เขตทารานากิ-คิง[250] เชน อาร์เดิร์นได้พ้นจากตำแหน่งในรัฐสภาตั้งแต่ ค.ศ. 2014 สามปีก่อนที่จาซินดา อาร์เดิร์นจะเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรี[251]

คู่ชีวิตของเธอ คลาร์ก เกย์ฟอร์ดทำงานเป็นผู้ดำเนินรายการโทรทัศน์[252][253] ทั้งคู่พบกันครั้งแรกใน ค.ศ. 2012 ผ่านคอริน มาทูรา-เจฟฟรี นางแบบและเจ้าของรายการโทรทัศน์ ผู้ซึ่งเพื่อนที่ทั้งคู่รู้จัก[254] แต่ตอนนั้นทั้งสองก็ยังไม่ได้คบหากันจนกระทั่งเกย์ฟอร์ดได้ติดต่อหาอาร์เดิร์นเกี่ยวกับร่างกฎหมายที่มีความขัดแย้งกับหน่วยข้อมูลและงานรักษาความปลอดภัย[252] เมื่อ 3 เมษายน ค.ศ. 2019 ได้มีการรายงานว่าได้อาร์เดิร์นได้เข้าพิธีหมั้นกับเกย์ฟอร์ดแล้ว พิธีสมรสได้กำหนดไว้ราวเดือนมกราคม ค.ศ. 2022 แต่ก็ต้องเลื่อนออกไปเนื่องจากการระบาดของไวรัส SARS-CoV-2 สายพันธุ์โอมิครอน[255][256]

วันที่ 19 มกราคม ค.ศ. 2018 อาร์เดิร์นได้ประกาศว่าเธอกำลังจะมีลูกคนแรกในเดือนมิถุนายน ทำให้เธอกลายเป็นนายกรัฐมนตรีนิวซีแลนด์คนแรกที่ตั้งครรภ์ระหว่างกำลังดำรงตำแหน่ง[257] อาร์เดิร์นได้คลอดบุตรสาวในวันที่ 21 มิถุนายน ค.ศ. 2018 ที่โรงพยาบาลนครออกแลนด์[258][259][260] เธอเป็นหัวหน้ารัฐบาลจากการเลือกตั้งคนที่สองของโลกที่ได้ให้กำเนิดบุตรขณะที่กำลังดำรงตำแหน่ง (คนแรกคือ เบนาซีร์ บุตโต ให้กำเนิดบุตรเมื่อ ค.ศ. 1990)[8][260] เธอได้ตั้งชื่อบุตรสาวของตนว่า นีฟ เต อะโรฮา (Neve Te Aroha)[261] Neve (นีฟ) เป็นขื่อที่แผลงจากคำว่า Niamh (นีฟ) ในภาษาไอริช มีความหมายว่าแสงสว่าง ส่วน Aroha (อะโรฮา) เป็นภาษามาวรี แปลว่าความรัก และ Te Aroha (เต อะโรฮา) เป็นชื่อเมืองเมืองหนึ่งในชนบทของนิวซีแลนด์ ตั้งอยู่ทางตะวันตกของเทือกเขาไคไม ใกล้กับมอร์รินส์วิลล์ บ้านเก่าของอาร์เดิร์น[262]

ดูเพิ่มเติม[แก้]

- List of New Zealand governments

- Politics of New Zealand

- Paddles (cat), Ardern's former pet cat

อ้างอิง[แก้]

- ↑ "Members Sworn". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). New Zealand Parliament. p. 2. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 23 February 2013.

- ↑ "Talking work-related hearing loss with NZ Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern". WorkSafe New Zealand. 28 September 2018. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 January 2022. สืบค้นเมื่อ 8 January 2022.

- ↑ Election results เก็บถาวร 6 ธันวาคม 2008 ที่ เวย์แบ็กแมชชีน

- ↑ Davison, Isaac (1 August 2017). "Andrew Little quits: Jacinda Ardern is new Labour leader, Kelvin Davis is deputy". The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 13 May 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "2017 General Election – Official Results". Electoral Commission. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 7 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Griffiths, James (19 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern to become New Zealand Prime Minister". CNN. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "The world's youngest female leader takes over in New Zealand". The Economist. 26 October 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 26 October 2017.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Khan, M Ilyas (21 June 2018). "Ardern and Bhutto: Two different pregnancies in power". BBC News. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 June 2018.

Now that New Zealand's Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has hit world headlines by becoming only the second elected head of government to give birth in office, attention has naturally been drawn to the first such leader – Pakistan's late two-time Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Murphy, Tim (1 August 2017). "What Jacinda Ardern wants". Newsroom. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 16 August 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 August 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Live: Jacinda Ardern answers NZ's questions". Stuff.co.nz. 3 August 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 August 2017.

- ↑ "Candidate profile: Jacinda Ardern". 3 News. 19 ตุลาคม 2011. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 11 มกราคม 2012. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 ธันวาคม 2011.

- ↑ Cumming, Geoff (24 September 2011). "Battle for Beehive hot seat". The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 30 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Bertrand, Kelly (30 June 2014). "Jacinda Ardern's country childhood". Now to Love. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Keber, Ruth (12 June 2014). "Labour MP Jacinda Ardern warms to Hairy and friends". เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 30 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019 – โดยทาง www.nzherald.co.nz.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern visits Morrinsville College". The New Zealand Herald. 10 August 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 1 March 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 28 February 2018.

- ↑ "Ardern, Jacinda: Maiden Statement". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). New Zealand Parliament. 16 December 2008. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 June 2018.

- ↑ Tanirau, Katrina (10 August 2017). "Labour leader Jacinda Ardern hits hometown in campaign trail". Stuff.co.nz. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 December 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 8 December 2019.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Ainge Roy, Eleanor (7 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern becomes youngest New Zealand Labour leader after Andrew Little quits". เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 September 2017.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (16 September 2017). "How Marie Ardern got her niece Jacinda into politics". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 17 September 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 17 September 2017.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Waikato BCS grad Jacinda Ardern becomes leader of the NZ Labour Party". University of Waikato. 2 August 2017. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 16 August 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 August 2017.

- ↑ "Ardern pays tribute to lives lost 20 years on from 9/11". เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 September 2021. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 September 2021.

- ↑ "'Jacindamania' sweeps New Zealand as it embraces a new prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, who isn't your average pol". Los Angeles Times. 9 March 2018. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 15 May 2021. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 September 2021.

- ↑ Tweed, David; Withers, Tracy (21 October 2017). "Kiwi PM Jacinda Ardern will be world's youngest female leader". The Sydney Morning Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 February 2018.

- ↑ Duff, Michelle. Jacinda Ardern: The Story Behind An Extraordinary Leader. Allen & Unwin. p. 70.

- ↑ "People – New Zealand Labour Party". คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 23 December 2008.

- ↑ Dudding, Adam (17 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern: I didn't want to work for Tony Blair". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 September 2017.

- ↑ "New Voices: Jacinda Ardern, Chris Hipkins and Jonathan Young". NZ Herald (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 3 March 2016. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 August 2021.

- ↑ Kirk, Stacey (1 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern says she can handle it and her path to the top would suggest she's right". The Dominion Post. Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 August 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern to lead IUSY". The Standard (ภาษาอังกฤษ). 31 January 2008. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 August 2021. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 August 2021.

- ↑ "Labour Party list for 2008 election announced | Scoop News". Scoop. 31 August 2008. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 31 July 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 August 2017.

- ↑ "Official Count Results – Waikato". electionresults.govt.nz. 2008. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 7 April 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (29 January 2010). "Greens' newest MP trains his sights on the bogan vote". The New Zealand Herald (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 April 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 April 2018.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Jacinda Ardern". New Zealand Parliament. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2 August 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Huffadine, Leith; Watkins, Tracy. "'Bridges and Ardern': the young guns who are now in charge". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 5 October 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 May 2018.

- ↑ Miller, Raymond (2015). Democracy in New Zealand (ภาษาอังกฤษ). Auckland University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-77558-808-5. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 October 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 November 2019.

- ↑ "Auckland Central electorate results 2011". Electionresults.org.nz. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 6 April 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 October 2017.

- ↑ "Official Count Results – Auckland Central". Electoral Commission. 4 October 2014. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 6 October 2014. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 October 2014.

- ↑ Small, Vernon (24 November 2014). "Little unveils new Labour caucus". Stuff. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 17 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Forum of Young Global Leaders". The Forum of Young Global Leaders (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 16 May 2021. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 February 2022.

- ↑ "Community". The Forum of Young Global Leaders (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 29 June 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 February 2022.

- ↑ Sachdeva, Sam (19 December 2016). "Labour MP Jacinda Ardern to run for selection in Mt Albert by-election". Stuff. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 December 2016. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 December 2016.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (15 September 2017). "'I've got what it takes': will Jacinda Ardern be New Zealand's next prime minister?". The Guardian. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 15 September 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern Labour's sole nominee for Mt Albert by-election". Stuff.co.nz. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 17 August 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 January 2017.

- ↑ Jones, Nicholas (12 January 2017). "Jacinda Ardern to contest Mt Albert byelection". The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 13 January 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern wins landslide victory Mt Albert by-election". The New Zealand Herald. 25 February 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 February 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Mt Albert – Preliminary Count". Electoral Commission. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 26 February 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 February 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern confirmed as Labour's new deputy leader". 6 March 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 November 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 July 2019 – โดยทาง www.nzherald.co.nz.

- ↑ "Labour's Raymond Huo set to return to Parliament after Maryan Street steps aside". The New Zealand Herald. 21 February 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 February 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 February 2017.

- ↑ "Andrew Little's full statement on resignation". The New Zealand Herald (ภาษาอังกฤษ). 31 July 2017. ISSN 1170-0777. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 24 May 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 May 2018.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern is Labour's new leader, Kelvin Davis as deputy leader". 7 August 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 13 May 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 31 July 2017.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Kwai, Isabella (4 September 2017). "New Zealand's Election Had Been Predictable. Then 'Jacindamania' Hit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 13 September 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 13 September 2017.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (31 July 2017). "Jacinda Ardern becomes youngest New Zealand Labour leader after Andrew Little quits". The Guardian. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 September 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 October 2017.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Little asked Ardern to lead six days before he resigned". The New Zealand Herald. 14 September 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 15 September 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 September 2017.

- ↑ "Donations to Labour surge as Jacinda Ardern named new leader". The New Zealand Herald. 2 August 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 1 September 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Video: Jacinda Ardern won't rule out capital gains tax". Radio New Zealand. 22 August 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Tarrant, Alex (15 August 2017). "Labour leader maintains 'right and ability' to introduce capital gains tax if working group suggests it next term; Would exempt family home". Interest.co.nz. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Kirk, Stacey (1 September 2017). "Jacinda Ardern tells Kelvin Davis off over capital gains tax comments". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Hickey, Bernard (24 September 2017). "Jacinda stumbled into a $520bn minefield". Newsroom. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (14 September 2017). "Election: Labour backs down on tax, will not introduce anything from working group until after 2020 election". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Steven Joyce still backing Labour's alleged $11.7b fiscal hole". Newshub. 19 September 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Farmers protest against Jacinda Ardern's tax policies". The New Zealand Herald. 18 September 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Labour leader Jacinda Ardern unshaken by Morrinsville farming protest". Newshub. 19 August 2017. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Vowles, Jack (3 July 2018). "Surprise, surprise: the New Zealand general election of 2017". Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 13 (2): 147–160. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2018.1443472.

- ↑ "Mt Albert – Official Result". Electoral Commission. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 15 January 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Preliminary results for the 2017 General Election". Electoral Commission. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "'Jacindamania' fails to run wild in New Zealand poll". The Irish Times. Reuters. 23 September 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "2017 General Election – Official Result". Electoral Commission. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 10 June 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Ardern and Davis to lead Labour negotiating team". Radio New Zealand. 26 September 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 26 September 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "NZ First talks with National, Labour begin". Stuff. 5 October 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2017.

- ↑ Haynes, Jessica. "Jacinda Ardern: Who is New Zealand's next prime minister?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Chapman, Grant. "New PM Jacinda Ardern joins an elite few among world, NZ leaders". Newshub. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 26 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Green Party ratifies confidence and supply deal with Labour". The New Zealand Herald. 19 October 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 October 2017.

- ↑ "New government ministers revealed". Radio New Zealand. 25 October 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern reveals ministers of new government". The New Zealand Herald. 26 October 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Small, Vernon (20 October 2017). "Predictable lineup of ministers as Ardern ministry starts to take shape". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 October 2017.

- ↑ "Ministerial List". Ministerial List. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 10 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Cheng, Derek (26 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern sworn in as new Prime Minister". The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Steafel, Eleanor (26 October 2017). "Who is New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern – the world's youngest female leader?". The Daily Telegraph. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 29 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "Premiers and Prime Ministers". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 12 December 2016. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 11 July 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 October 2017.

- ↑ "It's Labour! Jacinda Ardern will be next PM after Winston Peters and NZ First swing left". The New Zealand Herald. 19 October 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 October 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "Members – President Of The Council Of Women World Leaders". www.lrp.lt. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 13 September 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 13 September 2018.

- ↑ Atkinson, Neill. "Jacinda Ardern Biography". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern on baby news: 'I'll be Prime Minister and a mum'". Radio New Zealand. 19 January 2018. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 January 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 January 2018.

- ↑ "Winston Peters is now officially Acting Prime Minister". The New Zealand Herald. 21 June 2018. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Patterson, Jane (21 June 2018). "Winston Peters is in charge: His duties explained". Radio New Zealand. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 June 2018.

- ↑ "'Throw fatty out': Winston Peters fires insults on last day as PM". The New Zealand Herald (ภาษาอังกฤษ). 1 August 2018. ISSN 1170-0777. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 1 August 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Mercer, Phil (16 October 2018). "A country famed for quality of life faces up to child poverty". BBC News. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (2 July 2018). "Jacinda Ardern welcomes new welfare reforms from the sofa with new baby". The Guardian. Dunedin. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2 April 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 3 April 2019.

- ↑ "Supporting New Zealand families". Beehive.govt.nz. New Zealand Government. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2 April 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 April 2019.

- ↑ Biddle, Donna-Lee (28 November 2019). "Free lunches for low-decile school kids: What's on the menu?". Stuff.co.nz. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 28 November 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Andelane, Lana (19 April 2020). "$25 benefit increase 'making a difference' for beneficiaries during lockdown – Carmel Sepuloni". Newshub. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Klar, Rebecca (6 June 2020). "New Zealand providing free sanitary products in schools". The Hill. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 6 June 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 June 2020.

- ↑ Heyward, Emily (4 March 2018). "Blenheim to get 13 new state houses in nationwide pledge". Stuff.co.nz. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 7 January 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 April 2020.

- ↑ Neilson, Michael (25 January 2022). "Benefit increases go to 330,000 families – more than half in New Zealand". NZ Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 29 January 2022. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 February 2022.

- ↑ Molyneux, Vita (16 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Business expert condemns Government decision to raise minimum wage amid pandemic". Newshub. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Jones, Shane (23 February 2018). "Provincial Growth Fund open for business". New Zealand Government. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 February 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Jones, Nicholas (20 October 2017). "Jacinda Ardern confirms new government will dump tax cuts". The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 16 August 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Collins, Simon (26 June 2019). "Teachers accept pay deal – but principals reject it". The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 7 January 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (18 April 2019). "Week in Politics: Labour's biggest campaign burden scrapped". Radio New Zealand. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 April 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 April 2019.

- ↑ Williams, Larry. "Jack Tame: No CGT is 'enormous failure' for PM". Newstalk ZB. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 April 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 April 2019.

- ↑ "Ordinary New Zealanders bearing brunt of bright-line test". RNZ News. 29 January 2022. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 29 January 2022. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 February 2022.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Ainge-Roy, Eleanor (6 February 2018). "Jacinda Ardern defuses tensions on New Zealand's sacred Waitangi Day". The Guardian (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 16 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Sachdeva, Sam (6 February 2018). "Jacinda Ardern ends five-day stay in Waitangi". Newsroom (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบออสเตรเลีย). คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 16 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 June 2018.

- ↑ O'Brien, Tova; Hurley, Emma (9 July 2018). "Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern accepts Clare Curran's resignation as a minister". Newshub (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019.

- ↑ "Clare Curran situation has 'done real damage' to Jacinda Ardern and Government's credibility – Simon Bridges". TVNZ (ภาษาอังกฤษ). 7 September 2018. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Manhire, Toby (11 September 2019). "Timeline: Everything we know about the Labour staffer inquiry". The Spinoff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 15 May 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 29 April 2020.

- ↑ Vance, Andrea. "Labour Party president Nigel Haworth has resigned – but it's not over". Stuff (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 December 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 29 April 2020.

Ardern says she didn't know the allegations were sexual until this week. That's hard to swallow.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (12 September 2019). "Ardern under pressure as staffer accused of sexual assault quits". The Guardian. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 December 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 29 April 2020.

- ↑ "New Zealand sets 2020 cannabis referendum". BBC News (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบบริติช). 18 December 2018. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 17 October 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 3 June 2020.

- ↑ Cave, Damien (1 October 2020). "Jacinda Ardern Admits Having Used Cannabis. New Zealanders Shrug: 'Us Too.'". The New York Times. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 1 October 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 October 2020.

- ↑ "Official referendum results released". Electoral Commission. Electoral Commission. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 7 October 2021. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Rychert, Marta; Wilkins, Chris (7 March 2021). "Why did New Zealand's referendum to legalise recreational cannabis fail?". Drug and Alcohol Review. 40 (6): 877–881. doi:10.1111/dar.13254. PMID 33677836. S2CID 232140948.

- ↑ Walters, Laura; Small, Vernon. "Jacinda Ardern makes first state visit to Australia to strengthen ties". Stuff.co.nz. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 November 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 November 2017.

- ↑ Trevett, Claire (5 November 2017). "Key bromance haunts Jacinda Ardern's first Australia visit". The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 11 November 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern: Australia's deportation policy 'corrosive'". BBC News. 28 February 2020. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 1 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 March 2020.

- ↑ "Jacinda Ardern blasts Scott Morrison over Australia's deportation policy – video". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 28 February 2020. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 March 2020.

- ↑ Cooke, Henry (28 February 2020). "Extraordinary scene as Jacinda Ardern directly confronts Scott Morrison over deportations". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 March 2020.

- ↑ O'Meara, Patrick (9 November 2017). "PM heads to talks hoping to win TPP concessions". Radio New Zealand. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 9 November 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 November 2017.

- ↑ McCulloch, Craig (20 April 2018). "CHOGM: Ardern to toast Commonwealth at leaders' banquet". Radio New Zealand (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 April 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 April 2018.

- ↑ Ensor, Jamie; Lynch, Jenna (24 September 2019). "Jacinda Ardern, Donald Trump meeting: US President takes interest in gun buyback". Newshub (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 14 October 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 October 2019.

- ↑ Gambino, Lauren (23 September 2019). "Trump showed interest in New Zealand gun buyback program, Ardern says". The Guardian. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 14 October 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 October 2019.

- ↑ Coughlan, Thomas (30 October 2018). "Ardern softly raises concern over Uighurs". Newsroom. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 30 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Christian, Harrison (7 November 2018). "The disappearing people: Uighur Kiwis lose contact with family members in China". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Mutch Mckay, Jessica (14 November 2018). "Jacinda Ardern meets with Myanmar's leader, voices concern on Rohingya situation". TVNZ. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 30 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Bracewell-Worrall, Anna (5 September 2018). "'I am Prime Minister – I have a job to do': Jacinda Ardern defends separate Nauru flight". Newshub (ภาษาอังกฤษ). คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 7 September 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 8 September 2018.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (24 September 2018). "Jacinda Ardern makes history with baby Neve at UN general assembly". The Guardian (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 26 September 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 27 September 2018.

- ↑ Cole, Brendan. "Jacinda Ardern: New Zealand Prime Minister Makes History By Becoming First Woman to Bring Baby into U.N.Assembly". Newsweek. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 27 September 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 28 September 2018.

- ↑ "Full speech: 'Me too must become we too' – Jacinda Ardern calls for gender equality, kindness at UN". TVNZ (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 28 September 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "TPP deal revived once more, 20 provisions suspended". Radio New Zealand. 12 November 2017. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 3 April 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 May 2020.

- ↑ "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership" (PDF). New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 February 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 May 2020.

- ↑ Satherley, Dan (12 November 2017). "TPP 'a damned sight better' now – Ardern". Newshub.co.nz (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 May 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 May 2020.

- ↑ Wahlquist, Calla (24 March 2019). "An image of hope: how a Christchurch photographer captured the famous Ardern picture". The Guardian. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 31 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 April 2019.

- ↑ McConnell, Glenn (18 March 2019). "Face of empathy: Jacinda Ardern photo resonates worldwide after attack". The Sydney Morning Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 31 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 April 2019.

- ↑ Britton, Bianca (15 March 2019). "New Zealand PM full speech: 'This can only be described as a terrorist attack'". CNN. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 15 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 March 2019.

- ↑ "Three in custody after 49 killed in Christchurch mosque shootings". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 15 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 March 2019.

- ↑ Greenfield, Charlotte; Westbrook, Tom. "New gun laws to make NZ safer after mosque shootings, says PM Ardern". Reuters. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 March 2019.

- ↑ George, Steve; Berlinger, Joshua; Whiteman, Hilary; Kaur, Harmeet; Westcott, Ben; Wagner, Meg (19 March 2019). "New Zealand mosque terror attacks". CNN. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 March 2019.

- ↑ "Christchurch shootings: Ardern vows never to say gunman's name". BBC News. 19 March 2019. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 31 October 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Collman, Ashley (19 March 2019). "People around the world are praising New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern for her compassionate response to the Christchurch mosque shootings". Thisisinsider. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 October 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Newson, Rhonwyn (18 March 2019). "Christchurch terror attack: Jacinda Ardern praised for being 'compassionate leader'". Newshub. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 1 April 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 March 2019.

- ↑ "New Zealand's prime minister receives worldwide praise for her response to the mosque shootings". The Washington Post. 19 March 2019. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Shad, Saman (20 March 2019). "Five ways Jacinda Ardern has proved her leadership mettle". SBS World News. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 October 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 March 2019.

- ↑ Picheta, Rob. "Image of Jacinda Ardern projected onto world's tallest building". CNN. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 26 March 2019.

- ↑ Prior, Ryan. "A painter has revealed an 80-foot mural of New Zealand's prime minister comforting woman after mosque attacks". CNN. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 23 May 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 May 2019.

- ↑ Walls, Jason (16 March 2019). "Christchurch mosque shootings: New Zealand to ban semi-automatic weapons". nzherald.co.nz. The New Zealand Herald. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 May 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (19 March 2019). "Jacinda Ardern says cabinet agrees New Zealand gun reform 'in principle'". The Guardian. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 March 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 March 2019.

- ↑ Graham-McLay, Charlotte (10 April 2019). "New Zealand Passes Law Banning Most Semiautomatic Weapons, Weeks After Massacre". The New York Times (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบอเมริกัน). ISSN 0362-4331. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 24 May 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 3 June 2020.

- ↑ "Core group of world leaders to attend Jacinda Ardern-led Paris summit". The New Zealand Herald. 29 April 2019. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 23 June 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 June 2019.

- ↑ "Everyone travelling to NZ from overseas to self-isolate". Radio New Zealand. 14 March 2020. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 March 2020.

- ↑ Keogh, Brittany (14 March 2020). "Coronavirus: Prime Minister Ardern updates New Zealand on Covid-19 outbreak". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 14 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 March 2020.

- ↑ Whyte, Anna (19 March 2020). "PM places border ban on all non-citizens and non-permanent residents entering NZ". TVNZ (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 March 2020.

- ↑ "Live: PM Jacinda Ardern to give update on coronavirus alert level". Stuff (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 23 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 March 2020.

- ↑ Ensor, Jamie (24 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Jacinda Ardern's 'incredible', 'down to earth' leadership praised after viral video". Newshub. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Khalil, Shaimaa (22 April 2020). "Coronavirus: How New Zealand relied on science and empathy". BBC News. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 22 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Fifield, Anna (7 April 2020). "New Zealand isn't just flattening the curve. It's squashing it". The Washington Post. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 23 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Campbell, Alastair (11 April 2020). "Jacinda Ardern's coronavirus plan is working because, unlike others, she's behaving like a true leader". The Independent. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 23 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Boyle, Chelseas (23 April 2020). "Lockdown lawsuit fails: Legal action against Jacinda Ardern dismissed". The New Zealand Herald (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 24 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Earley, Melanie (23 April 2020). "Coronavirus: Man's lawsuit over Covid-19 lockdown restrictions dismissed". Stuff. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 27 April 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Trans-Tasman bubble: Jacinda Ardern gives details of Australian Cabinet meeting". Radio New Zealand. 5 May 2020. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 5 May 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Wescott, Ben (5 May 2020). "Australia and New Zealand pledge to introduce travel corridor in rare coronavirus meeting". CNN. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 5 May 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 May 2020.

- ↑ O'Brien, Tova (18 May 2020). "Newshub-Reid Research Poll: Jacinda Ardern goes stratospheric, Simon Bridges is annihilated". Newshub. MediaWorks TV. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 May 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 May 2020.

- ↑ "Pressure mounts as National falls to 29%, Labour skyrockets in 1 NEWS Colmar Brunton poll". 1 News. TVNZ. 21 May 2020. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 October 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 May 2020.

- ↑ Pandey, Swati (18 May 2020). "Ardern becomes New Zealand's most popular PM in a century – poll" (ภาษาอังกฤษ). คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 May 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 May 2020 – โดยทาง Reuters.

- ↑ O'Brien, Tova (18 May 2020). "Newshub-Reid Research Poll: Simon Bridges still confident he will lead National into election despite personal poll rating below 5 percent". Newshub. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 May 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 May 2020.

- ↑ "Political poll: Jacinda Ardern's numbers slump, Christopher Luxon up 13 points". RNZ News. 28 January 2022. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 29 January 2022. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 February 2022.

- ↑ "New Zealand election: Jacinda Ardern's Labour Party scores landslide win". BBC News. 17 October 2020. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 17 October 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 October 2020.