ผู้ใช้:Pilarbini/กระบะทราย/อาการท้องร่วง

| อาการท้องร่วง diarrhea | |

|---|---|

| |

| บัญชีจำแนกและลิงก์ไปภายนอก | |

| ICD-10 | A09, K59.1 |

| ICD-9 | 787.91 |

| DiseasesDB | 3742 |

| MedlinePlus | 003126 |

| eMedicine | ped/583 |

| MeSH | D003967 |

อาการท้องร่วง (อังกฤษ: diarrhea หรือ diarrhoea) เป็นภาวะมีการถ่ายอุจจาระเหลวหรือเป็นน้ำอย่างน้อยสามครั้งต่อวัน มักกินเวลาไม่กี่วันและอาจทำให้เกิดภาวะขาดน้ำจากการเสียสารน้ำ อาการแสดงของภาวะขาดน้ำมักเริ่มด้วยการเสียความตึงตัวของผิวหนังและบุคลิกภาพเปลี่ยน ซึ่งสามารถลุกลามเป็นการถ่ายปัสสาวะลดลง สีผิวหนังซีด อัตราหัวใจเต้นเร็ว และการตอบสนองลดลงเมื่อภาวะขาดน้ำรุนแรง อย่างไรก็ดี อุจจาระเหลวแต่ไม่เป็นน้ำในทารกที่กินนมแม่อาจเป็นปกติ[2]

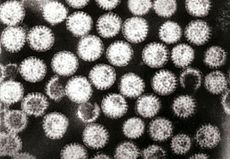

สาเหตุที่พบบ่อยที่สุด คือ การติดเชื้อของลำไส้อาจเนื่องจากไวรัส แบคทีเรียหรือปรสิต เป็นภาวะที่เรียก กระเพาะและลำไส้เล็กอักเสบ (gastroenteritis) การติดเชื้อเหล่านี้มักได้รับจากอาหารหรือน้ำที่มีการปนเปื้อนอุจจาระ หรือโดยตรงจากบุคคลอื่นที่ติดเชื้อ อาการท้องร่วงอารจแบ่งได้เป็นสามประเภท คือ อาการท้องร่วงเป็นน้ำระยะสั้น อาการท้องร่วงเป็นเลือดระยะสั้น และหากกินเวลานานกว่าสองสัปดาห์จะเป็นอาการท้องร่วงเรื้อรัง อาการท้องร่วงเป็นน้ำระยะสั้นอาจเนื่องจากการติดเชื้ออหิวาตกโรคซึ่งพบยากในประเทศพัฒนาแล้ว หากมีเลือดอยู่ด้วยจะเรียก โรคบิด[2] อาการท้องร่วงมีบางสาเหตุที่ไม่ได้เกิดจากการติดเชื้อซึ่งมีภาวะต่อมไทรอยด์ทำงานเกิน ภาวะไม่ทนต่อแล็กโทส (แพ้นม) โรคลำไส้อักเสบ ยาจำนวนหนึ่ง และกลุ่มอาการลำไส้ไวเกินต่อการกระตุ้น[3] ในผู้ป่วยส่วนมาก ไม่จำเป็นต้องเพาะเชื้ออุจจาระเพื่อยืนยันสาเหตุแน่ชัด[4]

การป้องกันอาการท้องร่วงจากการติดเชื้อทำได้โดยปรับปรุงการสุขาภิบาล มีน้ำดื่มสะอาดและล้างมือด้วยสบู่ แนะนำให้เลี้ยงลูกด้วยนมแม่อย่างน้อยหกเดือนเช่นเดียวกับการรับวัคซีนโรตาไวรัส สารน้ำเกลือแร่ (ORS) ซึ่งเป็นน้ำสะอาดที่มีเกลือและน้ำตาลปริมาณหนึ่ง เป็นการรักษาอันดับแรก นอกจากนี้ยังแนะนำยาเม็ดสังกะสี มีการประเมินว่าการรักษาเหล่านี้ช่วยชีวิตเด็ก 50 ล้านคนใน 25 ปีที่ผ่านมา[1] เมื่อบุคคลมีอาการท้องร่วง แนะนำให้กินอาหารเพื่อสุขภาพและทารกกินนมแม่ต่อไป หากหา ORS พาณิชย์ไม่ได้ อาจใช้สารละลายทำเองก็ได้[5] ในผู้ที่มีภาวะขาดน้ำรุนแรง อาจจำเป็นต้องให้สารน้ำเข้าหลอดเลือดดำ[2] ทว่า ผู้ป่วยส่วนมากสามารถรักษาได้ดีด้วยสารน้ำทางปาก[6] แม้ว่ามีการใช้ยาปฏิชีวนะน้อย แต่อาจแนะนำให้ผู้ป่วยซึ่งมีอาการท้องร่วงเป็นเลือดและไข้สูง ผู้ที่มีอาการท้องร่วงรุนแรงหลังท่องเที่ยว และผู้ที่เพาะแบคทีเรียหรือปรสิตบางชนิดขึ้นในอุจจาระ[4] โลเพอราไมด์อาจช่วยลดจำนวนการถ่ายอุจจาระ แต่ไม่แนะนำในผู้ป่วยรุนแรง[4]

มีผู้ป่วยอาการท้องร่วงประมาณ 1,700 ถึง 5,000 ล้านคนต่อปี[2][3] พบมากที่สุดในประเทศกำลังพัฒนาซึ่งเด็กเล็กมีอาการท้องร่วงโดยเฉลี่ย 3 ครั้งต่อปี[2] มีการประเมินยอดผู้เสียชีวิตจากอาการท้องร่วง 1.26 ล้านคนในปี 2556 ลดลงจาก 2.58 ล้านคนในปี 2533[7] ในปี 2555 อาการท้องร่วงเป็นสาเหตุการเสียชีวิตที่พบมากที่สุดอันดับสองในเด็กอายุน้อยกว่า 5 ปี (0.76 ล้านคนหรือ 11%)[2][8] คราวอาการท้องร่วงบ่อยยังเป็นสาเหตุทุพโภชนาการที่พบมากและเป็นสาเหตุที่พบมากที่สุดในเด็กอายุน้อยกว่าห้าปี[2] ปัญหาระยะยาวอื่นซึ่งอาจเกิดได้มีการเติบโตช้าและพัฒนาการทางสติปัญญาไม่ดี[8]

การป้องกัน[แก้]

สุขอนามัย[แก้]

[9]หลายงานวิจัยชี้ว่าการพัฒนาสุขอนามัยของน้ำดื่มลดความเสี่ยงของอาการท้องร่วง[10] ตัวอย่างเช่น การใช้ที่กรองน้ำ การพัฒนาคุณภาพของน้ำประปา และการพัฒนาระบบเชื่อมต่อท่อระบายของเสีย[10]

ในสถาบัน ชุมชน และบ้านเรือน การรณรงค์ให้ล้างเมือด้วยสบู่ลดอุบัติการณ์ของอาการท้องร่วง[11] เช่นเดียวกับการรณรงค์งดการขับถ่ายในที่แจ้งและการพัฒนาสุขอนามัย[12] เช่น การใช้ห้องน้ำ รวมไปถึงการขนย้ายของเสียอย่างถูกสุขลักษณะ

การล้างมือ[แก้]

หลักสุขอนามัยพื้นฐานส่งผลกระทบต่อการแพร่กระจายของโรคท้องร่วง การล้างมือด้วยน้ำและสบู่เป็นตัวอย่างหนึ่งที่แสดงให้เห็นจากการทดลองว่าสามารถลดอุบัติการณ์ของอาการท้องร่วงได้ถึง 42-48%[13][14] Hand washing in developing countries, however, is compromised by poverty as acknowledged by the CDC: "Handwashing is integral to disease prevention in all parts of the world; however, access to soap and water is limited in a number of less developed countries. This lack of access is one of many challenges to proper hygiene in less developed countries." Solutions to this barrier require the implementation of educational programs that encourage sanitary behaviours.[15]

Water[แก้]

Given that water contamination is a major means of transmitting diarrheal disease, efforts to provide clean water supply and improved sanitation have the potential to dramatically cut the rate of disease incidence. In fact, it has been proposed that we might expect an 88% reduction in child mortality resulting from diarrheal disease as a result of improved water sanitation and hygiene.[16][17] Similarly, a meta-analysis of numerous studies on improving water supply and sanitation shows a 22–27% reduction in disease incidence, and a 21–30% reduction in mortality rate associated with diarrheal disease.[18]

Chlorine treatment of water, for example, has been shown to reduce both the risk of diarrheal disease, and of contamination of stored water with diarrheal pathogens.[19]

Vaccination[แก้]

Immunization against the pathogens that cause diarrheal disease is a viable prevention strategy, however it does require targeting certain pathogens for vaccination. In the case of Rotavirus, which was responsible for around 6% of diarrheal episodes and 20% of diarrheal disease deaths in the children of developing countries, use of a Rotavirus vaccine in trials in 1985 yielded a slight (2-3%) decrease in total diarrheal disease incidence, while reducing overall mortality by 6-10%. Similarly, a Cholera vaccine showed a strong reduction in morbidity and mortality, though the overall impact of vaccination was minimal as Cholera is not one of the major causative pathogens of diarrheal disease.[20] Since this time, more effective vaccines have been developed that have the potential to save many thousands of lives in developing nations, while reducing the overall cost of treatment, and the costs to society.[21][22]

A rotavirus vaccine decrease the rates of diarrhea in a population.[1] New vaccines against rotavirus, Shigella, Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), and cholera are under development, as well as other causes of infectious diarrhea.แม่แบบ:Mcn

Nutrition[แก้]

Dietary deficiencies in developing countries can be combated by promoting better eating practices. Zinc supplementation proved successful showing a significant decrease in the incidence of diarrheal disease compared to a control group.[23][24] The majority of the literature suggests that vitamin A supplementation is advantageous in reducing disease incidence.[25] Development of a supplementation strategy should take into consideration the fact that vitamin A supplementation was less effective in reducing diarrhea incidence when compared to vitamin A and zinc supplementation, and that the latter strategy was estimated to be significantly more cost effective.[26]

Breastfeeding[แก้]

Breastfeeding practices have been shown to have a dramatic effect on the incidence of diarrheal disease in poor populations. Studies across a number of developing nations have shown that those who receive exclusive breastfeeding during their first 6 months of life are better protected against infection with diarrheal diseases.[27] Exclusive breastfeeding is currently recommended during, at least, the first six months of an infant's life by the WHO.[28]

Others[แก้]

Probiotics decrease the risk of diarrhea in those taking antibiotics.[29]

อ้างอิง[แก้]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "whqlibdoc.who.int" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Diarrhoeal disease Fact sheet N°330". World Health Organization. April 2013. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 July 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Doyle, edited by Basem Abdelmalak, D. John (2013). Anesthesia for otolaryngologic surgery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 282–287. ISBN 1107018676.

{{cite book}}:|first1=มีชื่อเรียกทั่วไป (help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 DuPont HL (Apr 17, 2014). "Acute infectious diarrhea in immunocompetent adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (16): 1532–40. doi:10.1056/nejmra1301069. PMID 24738670.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (ลิงก์) - ↑ Prober, edited by Sarah Long, Larry Pickering, Charles G. (2012). Principles and practice of pediatric infectious diseases (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier Saunders. p. 96. ISBN 9781455739851.

{{cite book}}:|first1=มีชื่อเรียกทั่วไป (help) - ↑ ACEP. "Nation's Emergency Physicians Announce List of Test and Procedures to Question as Part of Choosing Wisely Campaign". Choosing Wisely. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 June 2014.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=มีชื่อเรียกทั่วไป (help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Global Diarrhea Burden". CDC. January 24, 2013. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 June 2014.

- ↑ "Call to action on sanitation" (pdf). United Nations. เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 19 สิงหาคม 2014. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 สิงหาคม 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Wolf, Jennyfer; Prüss-Ustün, Annette; Cumming, Oliver; Bartram, Jamie; Bonjour, Sophie; Cairncross, Sandy; Clasen, Thomas; Colford, John M.; Curtis, Valerie; De France, Jennifer; Fewtrell, Lorna; Freeman, Matthew C.; Gordon, Bruce; Hunter, Paul R.; Jeandron, Aurelie; Johnston, Richard B.; Mäusezahl, Daniel; Mathers, Colin; Neira, Maria; Higgins, Julian P. T. (August 2014). "Systematic review: Assessing the impact of drinking water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease in low- and middle-income settings: systematic review and meta-regression". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 19 (8): 928–942. doi:10.1111/tmi.12331.

- ↑ Ejemot-Nwadiaro, Regina I.; Ehiri, John E.; Arikpo, Dachi; Meremikwu, Martin M.; Critchley, Julia A. (2015-09-03). "Hand washing promotion for preventing diarrhoea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD004265. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004265.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4563982. PMID 26346329.

- ↑ Spears, Dean; Ghosh, Arabinda; Cumming, Oliver (2013). "Open Defecation and Childhood Stunting in India: An Ecological Analysis of New Data from 112 Districts". PLoS ONE. PLoS ONE. 8 (9): e73784. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873784S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073784. PMC 3774764. PMID 24066070. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 กุมภาพันธ์ 2014. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 มีนาคม 2014.

- ↑ Curtis V, Cairncross S (May 2003). "Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 3 (5): 275–81. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00606-6. PMID 12726975.

- ↑ Cairncross S, Hunt C, Boisson S, Bostoen K, Curtis V, Fung IC, Schmidt WP (April 2010). "Water, sanitation and hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea". International Journal of Epidemiology. 39 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): i193–205. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq035. PMC 2845874. PMID 20348121.

- ↑ "Diarrheal Diseases in Less Developed Countries". CDC. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 4 พฤศจิกายน 2013. สืบค้นเมื่อ 28 ตุลาคม 2013.

- ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อBrown 629–34 - ↑ Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J (Jun 28, 2003). "Where and why are 10 million children dying every year?". Lancet. 361 (9376): 2226–34. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. PMID 12842379.

- ↑ Esrey SA, Feachem RG, Hughes JM (1985). "Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: improving water supplies and excreta disposal facilities". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 63 (4): 757–72. PMC 2536385. PMID 3878742.

- ↑ Arnold BF, Colford JM (February 2007). "Treating water with chlorine at point-of-use to improve water quality and reduce child diarrhea in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 76 (2): 354–64. PMID 17297049.

- ↑ de Zoysa I, Feachem RG (1985). "Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: rotavirus and cholera immunization". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 63 (3): 569–83. PMC 2536413. PMID 3876173.

- ↑ Rheingans RD, Antil L, Dreibelbis R, Podewils LJ, Bresee JS, Parashar UD (Nov 1, 2009). "Economic costs of rotavirus gastroenteritis and cost-effectiveness of vaccination in developing countries". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 200 Suppl 1: S16–27. doi:10.1086/605026. PMID 19817595.

- ↑ Oral cholera vaccines in mass immunization campaigns (PDF). WHO. 2010. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978 92 4 150043 2. เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 3 กันยายน 2014.

- ↑ Black RE (May 2003). "Zinc deficiency, infectious disease and mortality in the developing world". The Journal of Nutrition. 133 (5 Suppl 1): 1485S–9S. PMID 12730449.

- ↑ Bhutta ZA, Black RE, Brown KH, Gardner JM, Gore S, Hidayat A, Khatun F, Martorell R, Ninh NX, Penny ME, Rosado JL, Roy SK, Ruel M, Sazawal S, Shankar A (December 1999). "Prevention of diarrhea and pneumonia by zinc supplementation in children in developing countries: pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Zinc Investigators' Collaborative Group". The Journal of Pediatrics. 135 (6): 689–97. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70086-7. PMID 10586170.

- ↑ Mayo-Wilson E, Imdad A, Herzer K, Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA (Aug 25, 2011). "Vitamin A supplements for preventing mortality, illness, and blindness in children aged under 5: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 343: d5094. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5094. PMC 3162042. PMID 21868478.

- ↑ Chhagan MK, Van den Broeck J, Luabeya KK, Mpontshane N, Bennish ML (Aug 12, 2013). "Cost of childhood diarrhoea in rural South Africa: exploring cost-effectiveness of universal zinc supplementation". Public health nutrition. 17 (9): 1–8. doi:10.1017/S1368980013002152. PMID 23930984.

- ↑ "Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality". The Lancet. 355 (9202): 451–5. Feb 2000. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)82011-5. PMID 10841125.

- ↑ Sguassero Y. "Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: RHL commentary". WHO. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 3 พฤศจิกายน 2013. สืบค้นเมื่อ 14 ตุลาคม 2013.

- ↑ Hempel S, Newberry SJ, Maher AR, Wang Z, Miles JN, Shanman R, Johnsen B, Shekelle PG (9 May 2012). "Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 307 (18): 1959–69. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.3507. PMID 22570464.

แหล่งข้อมูลอื่น[แก้]

- Pilarbini/กระบะทราย/อาการท้องร่วง ที่เว็บไซต์ Curlie