ผลต่างระหว่างรุ่นของ "ภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือด"

แปลจากวิกิอังกฤษ ป้ายระบุ: ลิงก์แก้ความกำกวม |

(ไม่แตกต่าง)

|

รุ่นแก้ไขเมื่อ 14:23, 21 มีนาคม 2567

ลิงก์ข้ามภาษาในบทความนี้ มีไว้ให้ผู้อ่านและผู้ร่วมแก้ไขบทความศึกษาเพิ่มเติมโดยสะดวก เนื่องจากวิกิพีเดียภาษาไทยยังไม่มีบทความดังกล่าว กระนั้น ควรรีบสร้างเป็นบทความโดยเร็วที่สุด |

| ภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือด (Hypercholesterolemia) | |

|---|---|

| ชื่ออื่น | Hypercholesterolaemia, คอเลสเตอรอลสูง (high cholesterol) |

| |

| รูปแสดงถุงน้ำเลือดแช่แข็งที่ละลายแล้ว ถุงซ้ายได้มาจากผู้บริจาคที่มีภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือด มีระดับลิพิดในซีรั่มที่ผิดปกติ เทียบกับถุงขวาซึ่งได้จากผู้บริจาคปกติซึ่งมีระดับลิพิดในซีรั่มที่ปกติ | |

| สาขาวิชา | หทัยวิทยา |

| ภาวะแทรกซ้อน | โรคท่อเลือดแดงและหลอดเลือดแดงแข็ง, หลอดเลือดมีลิ่มเลือด, ภาวะสิ่งหลุดอุดหลอดเลือด, หัวใจวาย, โรคหลอดเลือดสมองเฉียบพลัน, ภาวะหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจมีลิ่มเลือด, ภาวะไขมันอุดหลอดเลือด, โรคระบบหัวใจหลอดเลือด |

| สาเหตุ | อาหารไม่ถูกสุขภาพ, อาหารที่ไม่มีคุณค่า, อาหารฟาสต์ฟู้ด, เบาหวาน, โรคพิษสุรา, monoclonal gammopathy, การล้างไต, กลุ่มอาการเนโฟรติก, ภาวะต่อมไทรอยด์ทำงานน้อย, กลุ่มอาการคุชิง, โรคเบื่ออาหารเหตุจิตใจ |

| โรคอื่นที่คล้ายกัน | ภาวะสารไขมันสูงในเลือด, ภาวะไทรกลีเซอไรด์สูงในเลือด |

ภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือด (อังกฤษ: hypercholesterolemia, high cholesterol) หรือ คอเลสเตอรอลสูง เป็นการมีคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือดสูง[1] เป็นรูปแบบหนึ่งของภาวะสารไขมันสูงในเลือด (hyperlipidemia), ของภาวะมีไลโพโปรตีนสูงในเลือด (hyperlipoproteinemia) และของภาวะไขมันในเลือดผิดปกติ (dyslipidemia)[1]

การมีคอเลสเตอรอลหนาแน่นต่ำ (LDL) และแบบอื่น ๆ ที่ไม่ใช่ HDL ในเลือดสูงอาจเป็นผลของอาหาร โรคทางพันธุกรรม (เช่น การกลายพันธุ์ของ LDL receptor ในภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือดชนิดครอบครัว) หรือการมีโรคอื่น ๆ เช่น เบาหวานชนิดที่ 2 และภาวะต่อมไทรอยด์ทำงานน้อย[1]

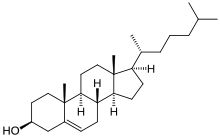

คอเลสเตอรอลเป็นลิพิดประเภทหนึ่งในลิพิดหลัก 3 อย่างที่เซลล์ทั้งหมดของสัตว์ผลิตและใช้เพื่อสร้างเยื่อหุ้มเซลล์ ส่วนเซลล์พืชผลิต phytosterol (ซึ่งคล้าย ๆ คอเลสเตอรอล) แต่เป็นจำนวนน้อยกว่า[2] คอเลสเตอรอลเป็นตัวตั้งต้นของฮอร์โมนสเตอรอยด์และกรดน้ำดี เพราะคอเลสเตอรอลละลายน้ำไม่ได้ จึงต้องขนส่งในเลือดโดยบรรจุในอนุภาคโปรตีน คือ ไลโพโปรตีน ไลโพโปรตีนสามารถจัดเป็นหมวด ๆ โดยความหนาแน่น คือ ไลโพโปรตีนหนาแน่นต่ำมาก (VLDL) ไลโพโปรตีนหนาแน่นปานกลาง (IDL) ไลโพโปรตีนหนาแน่นต่ำ (LDL) และไลโพโปรตีนหนาแน่นสูง (HDL)[3] ไลโพโปรตีนทุกชนิดมีหน้าที่บรรทุกคอเลสเตอรอลไป แต่การมีไลโพโปรตีนสูงนอกจาก HDL โดยเฉพาะ LDL ทำให้เสี่ยงมีภาวะหลอดเลือดแข็งและโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจเพิ่มขึ้น[4] ในนัยตรงกันข้าม การมี HDL สูงจะช่วยป้องกันโรคเหล่านั้น[5]

ในผู้ใหญ่ การหลีกเลี่ยงกินไขมันทรานส์และการแทนไขมันอิ่มตัวในอาหารด้วยไขมันไม่อิ่มตัวมีพันธะคู่หลายคู่ (polyunsaturated fats) เป็นวิธีการลดคอเลสเตอรอลรวมและ LDL ในเลือด[6][7] สำหรับคนที่มีคอเลสเตอรอลสูงมาก (เช่น มีภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือดชนิดครอบครัว) การเปลี่ยนอาหารมักจะไม่พอลด LDL ให้ถึงระดับที่ต้องการ ดังนั้น จึงต้องกินยาลดไขมัน[8] ถ้าจำเป็น มีวิธีการรักษาอื่น ๆ รวมทั้งการกรอง LDL ในเลือดออก (LDL apheresis) หรือแม้แต่การผ่าตัด (โดยเฉพาะผู้ที่มีภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือดชนิดครอบครัวแบบรุนแรง)[8]

รายงานผลสำรวจสุขภาพของสถาบันวิจัยระบบสาธารณสุขเมื่อปี พ.ศ. 2557 พบว่า ประชากรไทยอายุ 15 ปีขึ้นไป มีไขมันคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือดสูงเกินกว่ามาตรฐานที่กำหนด (200 มิลลิกรัม/เดซิลิตร) ถึงร้อยละ 44 หรือคิดเป็นจำนวนประมาณ 26 ล้านคน โดยแบ่งเป็นผู้ชายร้อยละ 41 และผู้หญิงร้อยละ 47[9]

อาการ

แม้ภาวะนี้โดยตนเองจะไม่มีอาการ แต่การมีคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือดนาน ๆ อาจก่อภาวะหลอดเลือดแข็ง คือไขมันเข้าไปเกาะในหลอดเลือดแดง[10] คือ เมื่อเวลาผ่านไปเป็นทศวรรษ ๆ ไขมันในเลือดสูงจะช่วยก่อตะกรันในท่อเลือดแดง (atheroma) ซึ่งจะทำให้ท่อเลือดค่อย ๆ แคบลง (stenosis) หรือตะกรันอาจจะหลุดออกไปอุดทางเดินของเลือด[11]

การอุดตันของเส้นเลือดแดงหล่อเลี้ยงหัวใจแบบฉับพลันอาจทำให้หัวใจวาย การอุดตันของเส้นเลือดหล่อเลี้ยงสมองอาจก่อโรคลมเหตุหลอดเลือดสมอง (stroke) ถ้าหลอดเลือดแคบลงอย่างค่อยเป็นค่อยไป เลือดก็จะไปเลี้ยงเนื้อเยื่อน้อยลงจนกระทั่งอวัยวะเริ่มมีปัญหา ในระยะนี้ การขาดเลือดของเนื้อเยื่อก็อาจปรากฏเป็นอาการโดยเฉพาะ ๆ ยกตัวอย่างเช่น ภาวะสมองขาดเลือดชั่วคราว (TIA) อาจปรากฏเป็นอาการชั่วคราวรวมทั้งการมองไม่เห็น คลื่นไส้ ทรงตัวไม่ดี พูดลำบาก อัมพฤกษ์ หรือความรู้สึกสัมผัสเพี้ยน (paresthesia) โดยปกติที่ข้างเดียวของร่างกาย การมีเลือดไปเลี้ยงหัวใจไม่พออาจก่ออาการปวดเค้นหัวใจ การมีเลือดไปเลี้ยงตาไม่พออาจทำให้มองไม่เห็นข้างเดียวชั่วคราว (amaurosis fugax) การมีเลือดไปเลี้ยงขาไม่พออาจทำให้ปวดน่องเมื่อเดิน (claudication) การมีเลือดไปเลี้ยงลำไส้ไม่พออาจทำให้ปวดท้องหลังอาหาร (abdominal angina)[1][12]

ภาวะนี้บางชนิดก่ออาการโดยเฉพาะ ๆ เช่น ภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือดชนิดครอบครัว (Type IIa hyperlipoproteinemia) สัมพันธ์กับกระเหลืองหนังตา (Xanthelasma palpebrarum) ซึ่งเป็นตุ่มเหลือง ๆ ที่หนังตาซึ่งมีคอเลสเตอรอลอยู่ข้างใน[13], กับ arcus senilis คือรอบ ๆ กระจกตาจะออกสีขาว ๆ หรือเทา ๆ[14] และกับ xanthomata ซึ่งเป็นการพอกไขมันที่เส้นเอ็นโดยมักเป็นที่นิ้ว[15][16] ส่วน Type III hyperlipoproteinemia อาจสัมพันธ์กับ xanthomata ของฝ่ามือ เข่า และศอก[15]

เหตุ

ภาวะนี้ปกติจะเกิดเพราะปัจจัยทางสิ่งแวดล้อมและพันธุกรรม[10] ปัจจัยทางสิ่งแวดล้อมรวมน้ำหนักตัว อาหาร และความเครียด[10][17] ความเหงาก็เป็นปัจจัยเสี่ยงด้วยเหมือนกัน[18]

อาหาร

อาหารมีผลต่อคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือด แต่มีผลเท่าไหร่จะขึ้นอยู่กับบุคคล[19][20] อาหารที่มีน้ำตาลมากหรือไขมันอิ่มตัวมาก จะเพิ่มระดับคอเลสเตอรอลรวมและ LDL[21] ไขมันทรานส์พบว่าลดระดับ HDL และเพิ่มระดับ LDL[22]

งานทบทวนปี 2016 พบหลักฐานเบื้องต้นว่า คอเลสเตอรอลในอาหารสัมพันธ์กับคอเลสเตอรอลที่สูงกว่าในเลือด[23] จนถึงปี 2018 การกินคอเลสเตอรอลดูเหมือนจะสัมพันธ์กับระดับ LDL อย่างพอสมควรในเชิงบวก[24]

โรคและการรักษา

ภาวะอื่น ๆ ที่เพิ่มระดับคอเลสเตอรอลได้รวมทั้ง เบาหวานชนิดที่ 2, โรคอ้วน, การดื่มสุรา, monoclonal gammopathy คือการมี myeloma protein หรือ monoclonal gamma globulin สูงเกินในเลือด, การล้างไต, กลุ่มอาการเนโฟรติก, ภาวะต่อมไทรอยด์ทำงานน้อย, กลุ่มอาการคุชิง และโรคเบื่ออาหารเหตุจิตใจ[10] ยาหลายชนิดอาจขัดขวางเมแทบอลิซึมของลิพิด รวมทั้ง thiazide diuretics, ciclosporin, กลูโคคอร์ติคอยด์, เบตาบล็อกเกอร์, retinoic acid, ยาระงับอาการทางจิต[10], ยากันชักบางอย่าง และยารักษาเอชไอวีรวมทั้งอินเตอร์เฟียรอน[25]

กรรมพันธุ์

เหตุทางพันธุกรรมมักจะมาจากยีนหลายตัวรวม ๆ กัน (polygenic) แต่ในบางกรณี อาจมาจากความบกพร่องของยีนตัวเดียว ดังที่พบในภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือดชนิดครอบครัว[10] ซึ่งการกลายพันธุ์อาจอยู่ในยีน APOB (Apolipoprotein B) โดยเกิดจากยีนเด่น หรือในยีน LDLRAP1 (Low-density lipoprotein receptor adapter protein 1) โดยเกิดจากยีนด้อย หรือรูปผันแปร HCHOLA3 ของยีน PCSK9 โดยเกิดจากยีนเด่น หรือในยีน LDLR (receptor gene)[26] ภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูงในเลือดชนิดครอบครัวเกิดใน 1/250 คน[27]

กลุ่มคนยิวลิตแว็กส์ที่มีรากฐานเดิมจากแกรนด์ดัชชีลิทัวเนียอาจมีปัญหาทางกรรมพันธุ์ที่เกิดจากปรากฏการณ์ผู้ก่อตั้ง (founder effect)[28] มีภาวะโรคชนิด G197del LDLR ซึ่งสืบสาวลักษณะทางพันธุกรรมไปได้จนถึงศตวรรษที่ 14[29]

การวินิจฉัย

| ประเภท | mmol/L | mg/dL | การตีความหมาย |

|---|---|---|---|

| คอเลสเตอรอลรวม | <5.2 | <200 | ดี[30] |

| 5.2-6.2 | 200-239 | คาบเส้น[30] | |

| >6.2 | >240 | สูง[30] | |

| คอเลสเตอรอล LDL | <2.6 | <100 | ดีสุด[30] |

| 2.6-3.3 | 100-129 | ดี[30] | |

| 3.4-4.1 | 130-159 | คาบเส้นสูง[30] | |

| 4.1-4.9 | 160-189 | สูงและไม่ดี[30] | |

| >4.9 | >190 | สูงมาก[30] | |

| HDL cholesterol | <1.0 | <40 | ไม่ดี เสี่ยงขึ้น[30] |

| 1.0-1.5 | 41-59 | โอเค[30] | |

| >1.55 | >60 | ดี เสี่ยงลดลง[30] |

คอเลสเตอรอลมีหน่วยวัดเป็นมิลลิกรัม/เดซิลิตร (mg/dL) ในบางประเทศรวมทั้งประเทศไทย[31] ในสหราชอาณาจักร ในประเทศยุโรปโดยมาก และในแคนาดา หน่วยวัดจะเป็นมิลลิโมล/ลิตร[32]

สถาบันหัวใจปอดและเลือดแห่งชาติอันเป็นส่วนของสถาบันสุขภาพแห่งชาติสหรัฐ จัดคอเลสเตอรอลรวมที่น้อยกว่า 200 mg/dL ว่า "พึงประสงค์"/ดี, ที่ระหว่าง 200-239 mg/dL ว่า "คาบเส้นสูง" และ 240 mg/dL ขึ้นว่า "สูง"[33]

ไม่มีเส้นตายแบ่งระดับคอเลสเตอรอลว่าปกติหรือผิดปกติ เพราะต้องเทียบกับสุขภาพทั่วไปและปัจจัยเสี่ยง[34][35][36]

ระดับคอเลสเตอรอลรวมที่สูงกว่าจะเพิ่มความเสี่ยงโรคระบบหัวใจหลอดเลือดโดยเฉพาะโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจ[37] ระดับคอเลสเตอรอลทั้งแบบ LDL และ non-HDL สามารถใช้พยากรณ์โรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจ แต่อะไรพยากรณ์ได้ดีกว่าก็ยังไม่มีข้อยุติ[38] การมี LDL ซึ่งมีอนุภาคเล็กและหนาแน่นในระดับสูงอาจจะอันตรายเป็นพิเศษ แต่การวัด LDL ก็ไม่แนะนำเพื่อใช้พยากรณ์ความเสี่ยง[38] ในอดีต ระดับ LDL และ VLDL มักจะไม่ได้วัดโดยตรงเพราะค่าใช้จ่ายสูง[39][40][41]

ระดับไตรกลีเซอไรด์หลังอดอาหารได้ใช้เป็นค่าระบุระดับ VLDL (ทั่วไปแล้ว 45% ของไตรกลีเซอไรด์หลังอดอาหารจะเป็น VLDL) เทียบกับค่า LDL ซึ่งปกติจะประมาณด้วยสูตรของ Friedewald คือ

LDL คอเลสเตอรอลรวม – HDL – (0.2 x ไตรกลีเซอไรด์หลังอดอาหาร)[42]

แต่สูตรนี้ใช้ไม่ได้เมื่อไม่อดอาหาร หรือว่าค่าไตรกลีเซอไรด์สูงคือ >4.5 mmol/L หรือ >~400 mg/dL ดังนั้น แนวทางปฏิบัติเร็ว ๆ นี้ได้สนับสนุนให้ใช้วิธีการวัดค่า LDL โดยตรงเมื่อเป็นไปได้[38] แต่เมื่อใช้ตรวจภาวะนี้ การวัดไลโพโปรตีนต่างหาก ๆ ทั้งหมดรวมทั้ง VLDL, IDL, LDL และ HDL รวมทั้ง apolipoproteins และ lipoprotein (a) ก็อาจเป็นประโยชน์ด้วย[38] ปัจจุบันจะแนะนำการตรวจพันธุกรรมถ้าสงสัยว่ามีภาวะนี้ชนิดครอบครัว[38]

การจัดหมวด

ดั้งเดิมแล้ว ภาวะนี้ได้จัดหมวดอาศัยการแยกไลโพโปรตีนด้วยอิเล็กโตรโฟรีซิสแล้วจัดหมวดด้วย Fredrickson classification แต่ก็มีวิธีใหม่ ๆ เช่น lipoprotein subclass analysis ซึ่งดีกว่าเพราะช่วยให้เข้าใจความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างการดำเนินของโรคหลอดเลือดแดงแข็งกับผลทางคลินิก ถ้าเป็นภาวะแบบกรรมพันธุ์ คือ familial hypercholesterolemia ปกติประวัติครอบครัวก็จะมีโรคหลอดเลือดแดงแข็งที่เกิดก่อนวัย[43]

การตรวจคัดกรอง

คณะกรรมการป้องกันโรคสหรัฐ (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force) แนะนำอย่างหนักแน่นในปี 2008 ให้ตรวจคัดกรองชายอายุตั้งแต่ 35 ปี และหญิงอายุตั้งแต่ 45 ปีสำหรับโรคไขมัน และให้รักษาผู้ผ่านเกณฑ์ที่เสี่ยงโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจ และก็แนะนำให้ตรวจคัดกรองชายอายุระหว่าง 20-35 ปี และหญิงอายุ 20-45 ปีถ้ามีปัจจัยเสี่ยงอื่น ๆ ของโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจ[44] ในปี 2016 คณะกรรมการได้สรุปว่า การตรวจประชากรทั่วไปที่มีอายุต่ำกว่า 40 ปีและไม่มีอาการ มีประโยชน์ที่ไม่ชัดเจน[45][46]

ประเทศแคนาดาแนะนำให้ตรวจคัดกรองชายอายุตั้งแต่ 40 ปีขึ้นและหญิงอายุตั้งแต่ 50 ปีขึ้น[47] สำหรับผู้มีระดับคอเลสเตอรอลปกติ แนะนำให้ตรวจคัดกรองทุก 5 ปี[48] เมื่อเริ่มกินยาลดไขมันคือสแตตินแล้ว ก็ไม่จำเป็นต้องตรวจคอเลสเตอรอลอีกต่อไป ยกเว้นเพื่อจะดูว่าคนไข้ให้ความร่วมมือในการรักษาหรือไม่[49]

การรักษา

การรักษาจะขึ้นอยู่กับระดับความเสี่ยงเป็นโรคหัวใจ โดยแบ่งเป็น 4 ระดับ[50] ซึ่งใช้ระดับคอเลสเตอรอล LDL เป็นเป้าหมายและขีดเริ่มเปลี่ยนในการรักษาวิธีต่าง ๆ[50] ระดับเสี่ยงยิ่งสูงเท่าไร ขีดเริ่มเปลี่ยนของคอเลสเตอรอลก็ต่ำลงเท่านั้น[50]

| ความเสี่ยง | เกณฑ์ | เปลี่ยนวิถีการใช้ชีวิต | เปลี่ยนยา | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| จำนวนปัจจัยเสี่ยง† | ความเสี่ยงใน 10 ปีที่จะมี โรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจ |

mmol/litre | mg/dL | mmol/litre | mg/dL | ||

| สูง | เป็นโรคหัวใจมาก่อน | หรือ | >20% | >2.6[51] | >100 | >2.6 | >100 |

| เกือบสูง | 2 หรือยิ่งกว่า | และ | 10-20% | >3.4 | >130 | >3.4 | >130 |

| ปานกลาง | 2 หรือยิ่งกว่า | และ | <10% | >3.4 | >130 | >4.1 | >160 |

| ต่ำ | 0 หรือ 1 | >4.1 | >160 | >4.9 | >190 | ||

| †ปัจจัยเสี่ยงรวมการสูบบุหรี่ ความดันสูง (BP ≥140/90 mm Hg หรือกินยาความดันสูง), คอเลสเตอรอล HDL ต่ำ (<40 mg/dL), ประวัติครอบครัวที่มีโรคหัวใจก่อนวัย, อายุ (ชาย ≥45 ปี; หญิง ≥55 ปี) | |||||||

สำหรับผู้เสี่ยงสูง การเปลี่ยนวิถีชีวิตบวกกับการกินยาสแตตินพบว่า ลดอัตราการตาย[10]

วิถีชีวิต

วิถีชีวิตที่แนะนำให้เปลี่ยนสำหรับผู้มีคอเลสเตอรอลสูงรวมทั้งเลิกสูบบุหรี่ จำกัดการดื่มสุรา เพิ่มออกกำลังกาย และรักษาน้ำหนักให้อยู่ในเกณฑ์[19] คนน้ำหนักเกินหรือเป็นโรคอ้วนสามารถลดคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือดโดยการลดน้ำหนัก โดยเฉลี่ยแล้ว การลดน้ำหนักหนึ่งกิโลกรัมสารถลดคอเลสเตอรอล LDL ได้ 0.8 mg/dl[8]

อาหาร

การทานอาหารที่มีผัก ผลไม้ และใยอาหารมาก มีไขมันต่ำ จะทำให้ลดคอเลสเตอรอลรวมได้พอสมควร[52][53][8]

การได้คอเลสเตอรอลจากอาหาร จะทำให้ระดับในเลือดสูงขึ้นเล็กน้อย[54][55] โดยสูงขึ้นแค่ไหนจะพยากรณ์ได้โดยใช้สูตรของคียส์[56][A] และสูตรของเฮ็กสเต็ด (อังกฤษ: Hegsted equation)[59][B]

เคยมีแนวทางปฏิบัติให้จำกัดคอเลสเตอรอลในอาหารในสหรัฐ แต่ไม่มีในแคนาดา ในสหราชอาณาจักร และในออสเตรเลีย[54] อย่างไรก็ดี ในปี 2015 สหรัฐก็ได้เลิกข้อแนะนำให้จำกัดคอเลสเตอรอลจากอาหาร[62]

งานปริทัศน์เป็นระบบของคอเคลนปี 2020 พบว่าการแทนไขมันอิ่มตัวด้วยไขมันไม่อิ่มตัวลดโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือดลงเล็กน้อยเพราะลดคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือด[63] แต่งานปริทัศน์เป็นระบบอื่น ๆ กลับไม่พบผลของไขมันอิ่มตัวต่อโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือด[64][7] ไขมันทรานส์จัดเป็นปัจจัยเสี่ยงสำหรับโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือดที่เกี่ยวกับคอเลสเตอรอล ดังนั้นจึงแนะนำให้ผู้ใหญ่หลีกเลี่ยงไขมันทรานส์[7] สมาคมลิพิดแห่งชาติสหรัฐ (NLA) แนะนำให้ผู้ที่มีภาวะโรคชนิดครอบครัวจำกัดการกินไขมันให้เหลือเพียง 25-35% ของพลังงานทั้งหมดที่ได้[8] สำหรับอาหารที่มีพลังงานต่ำ การเปลี่ยนการกินไขมันดูเหมือนจะไม่มีผลต่อคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือด[65]

การเพิ่มกินใยอาหารที่ละลายน้ำได้พบว่า ลดระดับคอเลสเตอรอลแบบ LDL ได้โดยใยอาหารแต่ละกรัมจะลด LDL โดยเฉลี่ย 2.2 mg/dL (0.057 mmol/L)[66] การเพิ่มกินธัญพืชแบบไม่ขัดสียังพบว่าลดคอเลสเตอรอลแบบ LDL ได้ด้วย โดยข้าวโอ๊ตไม่ขัดสีให้ผลดีเป็นพิเศษ[67] การเพิ่ม phytosterols และ phytostanols จากพืช 2 กรัม/วัน และไฟเบอร์ละลายน้ำได้ 10-20 กรัม/วัน พบว่าลดการดูดซึมคอเลสเตอรอลจากอาหาร[8] อาหารที่มีฟรักโทสมากสามารถเพิ่มระดับคอเลสเตอรอล LDL ในเลือด[68]

ยา

แพทย์มักจะรักษาโดยสั่งยาสแตตินและให้เปลี่ยนการดำเนินชีวิตให้ถูกสุขภาพยิ่งขึ้น[69] สแตตินสามารถลดคอเลสเตอรอลรวมประมาณครึ่งหนึ่งสำหรับคนโดยมาก[38] และมีประสิทธิภาพลดความเสี่ยงโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือดในคนทั้งที่มี[70] และไม่มีโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือดมาก่อน[71][72][73][74] ในบุคคลที่ไม่มีโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือด สแตตินพบว่าลดอัตราการตายจากเหตุทั้งหมด ลดโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจทั้งที่ถึงตายและไม่ถึงตาย และลดโรคหลอดเลือดสมองเฉียบพลัน[75] โดยประโยชน์จะยิ่งขึ้นเมื่อให้กินยามาก (high-intensity statin therapy)[76] สแตตินอาจเพิ่มคุณภาพชีวิตสำหรับบุคคลที่ไม่มีโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือดมาก่อน (คือเพื่อป้องกันโรคระดับปฐมภูมิ)[75] แม้สแตตินจะลดระดับคอเลสเตอรอลในเด็กที่มีโรคนี้ แต่จนถึงปี 2010 ก็ไม่พบว่าทำให้ได้ผลลัพธ์ที่ดีขึ้น[77] และจริง ๆ การเปลี่ยนอาหารก็เป็นวิธีรักษาหลักสำหรับเด็ก[38]

ยาอื่น ๆ ที่หมออาจจะให้รวมทั้ง fibrate, ไนอาซิน และคอเลสไตรามีน[78] แต่ปกติ นี้จะแนะนำก็ต่อเมื่อคนไข้ทนรับสแตตินไม่ได้ หรือสำหรับหญิงมีครรภ์[78] สารภูมิต้านทานสำหรับฉีดต่อต้านโปรตีน PCSK9 (รวมทั้ง evolocumab, bococizumab, alirocumab) ลดคอเลสเตอรอลได้ และพบว่าลดอัตราการตายด้วย[79]

แนวทางปฏิบัติ

ประเทศไทยมีแนวทางเวชปฏิบัตการใช้ยารักษาภาวะไขมันผิดปกติเพื่อป้องกันโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือด พ.ศ. ๒๕๕๙ จากสมาคมโรคหลอดแดงแห่งประเทศไทย โดยได้รับอนุญาตจากราชวิทยาลัยอายุรแพทย์แห่งประเทศไทย[80]

กลุ่มประชากรโดยเฉพาะ ๆ

สำหรับผู้มีการคาดหมายคงชีพค่อนข้างสั้น ภาวะนี้จะไม่ใช่ปัจจัยเสี่ยงให้ตายไม่ว่าจะด้วยเหตุใด ๆ แม้กระทั่งโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจ[81] สำหรับผู้อายุมากกว่า 70 ปี ภาวะนี้ไม่ใช่ปัจจัยเสี่ยงให้เข้าโรงพยาบาลเนื่องกับกล้ามเนื้อหัวใจตายเหตุขาดเลือดหรืออาการปวดเค้นหัวใจ[81] สำหรับผู้อายุเกิน 85 ปี การใช้ยาสแตตินจะเสี่ยงเพิ่มขึ้น[81] ด้วยเหตุนี้ ยาลดระดับลิพิดจึงไม่ควรใช้เป็นปกติกับผู้มีการคาดหมายคงชีพจำกัด[81] American College of Physicians แนะนำการรักษาผู้มีภาวะนี้ที่มีเบาหวาน คือ[82]

- ควรใช้ยาลดลิพิดเป็นการป้องกันในระดับทุติยภูมิ เพื่อป้องกันความตายและภาวะเนื่องกับโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือดสำหรับผู้ใหญ่ ที่มีโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจและเบาหวานชนิด 2

- สแตตินควรใช้เป็นการป้องกันในระดับปฐมภูมิ เพื่อป้องกันภาวะแทรกซ้อนจากโรคหลอดเลือดเลี้ยงหัวใจ โรคหลอดเลือดสมอง หรือโรคหลอดเลือดส่วนปลาย สำหรับผู้ใหญ่ที่มีเบาหวานชนิด 3 และปัจจัยเสี่ยงโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือดอื่น ๆ

- หลังจากที่เริ่มการรักษาเพื่อลดลิพิด คนที่มีเบาหวานชนิด 2 ควรจะกินยาสแตตินในขนาดปานกลาง (moderate) เป็นอย่างน้อย[83]

- สำหรับคนไข้เบาหวานชนิด 2 ที่กินยาสแตติน การตรวจการทำงานของตับหรือตรวจเอนไซม์จากกล้ามเนื้อไม่แนะนำยกเว้นในกรณีโดยเฉพาะ ๆ

แพทย์ทางเลือก

งานสำรวจปี 2002 ของสหรัฐพบว่า ในบรรดาผู้ใหญ่ที่ใช้การรักษาโดยแพทย์ทางเลือก มี 1.1% เท่านั้นที่ใช้เพื่อรักษาภาวะคอเลสเตอรอลสูง 55% ของคนไข้เหล่านั้นใช้ร่วมกับการรักษาของแพทย์ปัจจุบันโดยเหมือนกับการสำรวจครั้งก่อน ๆ[84] งานปริทัศน์เป็นระบบปี 2011[85] เกี่ยวกับประสิทธิภาพของยาจีนได้ผลที่สรุปไม่ได้เพราะงานที่มีให้ทบทวนใช้ระเบียบวิธีที่ไม่ดี งานทบทวนปี 2009 พบว่าการใช้ยา phytosterols และ/หรือ phytostanols โดยเฉลี่ย 2.15 กรัมต่อวันลดคอเลสเตอรอล LDL ได้ 9% โดยเฉลี่ย[86] ในปี 2000 องค์การอาหารและยาสหรัฐได้อนุมัติการลงป้ายอาหารที่มี phytosterol หรือ phytostanol ตามจำนวนที่กำหนดว่า ช่วยลดคอเลสเตอรอล แต่ในปี 2003 ก็ขยายอนุญาตให้ใช้ป้ายสำหรับทั้งอาหารและอาหารเสริมที่ให้ phytosterol หรือ phytostanol เกิน 0.8 กรัมต่อวัน แต่นักวิจัยบ้างพวกก็เป็นห่วงเรื่องการมีอาหารเสริมที่เป็นเอสเทอร์สเตอรอลของพืช และชี้ว่าไม่มีข้อมูลความปลอดภัยในระยะยาว[87]

วิทยาการระบาด

รายงานผลสำรวจสุขภาพของสถาบันวิจัยระบบสาธารณสุขเมื่อปี พ.ศ. 2557 พบว่า ประชากรไทยอายุ 15 ปีขึ้นไป มีไขมันคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือดสูงเกินกว่ามาตรฐานที่กำหนด (200 มิลลิกรัม/เดซิลิตร) ถึงร้อยละ 44 หรือคิดเป็นจำนวนประมาณ 26 ล้านคน โดยแบ่งเป็นผู้ชายร้อยละ 41 และผู้หญิงร้อยละ 47[9]

ทิศทางงานวิจัย

วิธีรักษาใหม่ที่กำลังศึกษาก็คือการรักษาด้วยยีน (gene therapy)[88][89]

เชิงอรรถ

- ↑ สูตรของคียส์ (อังกฤษ: Keys equation) สามารถใช้พยากรณ์ผลของกรดไขมันอิ่มตัวและไม่อิ่มตัวในอาหารต่อระดับคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือด

นพ. ชาวอเมริกัน แอนเซล คียส์ ได้ค้นพบว่า ไขมันอิ่มตัวในอาหารจะเพิ่มระดับคอเลสเตอรอลรวมและคอเลสเตอรอล LDL โดยเพิ่มเป็นสองเท่าของที่ไขมันไม่อิ่มตัวลดคอเลสเตอรอลเหล่านั้น[57]

การเปลี่ยนแปลงของคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือดมีสูตรเป็น[58]

- (mmol/L) = 0.031(2Dsf − Dpuf) + 1.5√Dch

- ↑ ศาสตราจารย์เฮ็กสเต็ดแห่งมหาวิทยาลัยฮาร์วาร์ดได้ทำงานวิจัยในช่วงต้นคริสต์ทศวรรษ 1960 เรื่องความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างอาหารกับระดับคอเลสเตอรอลในเลือด สูตรที่เขาตั้งขึ้นแสดงว่า คอเลสเตอรอลและไขมันอิ่มตัวจากอาหารเช่นไข่และเนื้อ จะเพิ่มระดับคอเลสเตอรอลที่ไม่ดีในเลือด แต่ไขมันไม่อิ่มตัวมีพันธะคู่เดียว (monounsaturated fat) แทบไม่มีผล ส่วนไขมันไม่อิ่มตัวมีพันธะคู่หลายคู่จากอาหารเช่นถั่วและเมล็ดพืช จะลดระดับคอเลสเตอรอล เป็นงานวิจัยที่ตีพิมพ์ในปี 1965[60] เมื่อรวมกับงานศึกษาที่แอนเซล คียส์ ทำต่างหาก ๆ จึงเกิดคำแนะนำให้ลดการทานไขมันอิ่มตัว สูตรของเฮ็กสเต็ด (อังกฤษ: Hegsted equation) สามารถใช้พยากรณ์ผลของอาหารต่อคอเลสเตอรอลรวมในเลือด คือ เมื่อ = กรดไขมันอิ่มตัว (% ของแคลอรีทั้งหมด), = กดไขมันไม่อิ่มตัวมีพันธะคู่หลายคู่ (% ของแคลอรีทั้งหมด) และ = คอเลสเตอรอลจากอาหาร[61]

อ้างอิง

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Durrington, P (August 2003). "Dyslipidaemia". Lancet. 362 (9385): 717–731. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14234-1. PMID 12957096. S2CID 208792416.

- ↑ Behrman, EJ; Gopalan, V (December 2005). "Cholesterol and Plants". Journal of Chemical Education. 82 (12): 1791. Bibcode:2005JChEd..82.1791B. doi:10.1021/ed082p1791. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ↑ Biggerstaff, KD; Wooten, JS (December 2004). "Understanding lipoproteins as transporters of cholesterol and other lipids". Advances in Physiology Education. 28 (1–4): 105–106. doi:10.1152/advan.00048.2003. PMID 15319192. S2CID 30197456.

- ↑ Carmena, R; Duriez, P; Fruchart, JC (June 2004). "Atherogenic lipoprotein particles in atherosclerosis". Circulation. 109 (23 Suppl 1): III2–III7. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000131511.50734.44. PMID 15198959.

- ↑ Kontush, A; Chapman, MJ (March 2006). "Antiatherogenic small, dense HDL--guardian angel of the arterial wall?". Nature Clinical Practice. Cardiovascular Medicine. 3 (3): 144–153. doi:10.1038/ncpcardio0500. PMID 16505860. S2CID 27738163.

- ↑ "Healthy diet - Fact sheet N°394". World Health Organization. September 2015. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2016-07-06.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 de Souza, RJ; Mente, A; Maroleanu, A; Cozma, AI; Ha, V; Kishibe, T; และคณะ (August 2015). "Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". BMJ. 351: h3978. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3978. PMC 4532752. PMID 26268692.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Ito, MK; McGowan, MP; Moriarty, PM (June 2011). "Management of familial hypercholesterolemias in adult patients: recommendations from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia". Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 5 (3 Suppl): S38–S45. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2011.04.001. PMID 21600528.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Official, ThaiHealth (2017-04-04). "คนไทย 26 ล้านคนไขมันในเลือดสูง". สำนักงานกองทุนสนับสนุนการสร้างเสริมสุขภาพ (สสส.). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2024-03-15. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-15.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Bhatnagar, D; Soran, H; Durrington, PN (August 2008). "Hypercholesterolaemia and its management". BMJ. 337: a993. doi:10.1136/bmj.a993. PMID 18719012. S2CID 5339837.

- ↑ Finn, AV; Nakano, M; Narula, J; Kolodgie, FD; Virmani, R (July 2010). "Concept of vulnerable/unstable plaque". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 30 (7): 1282–1292. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179739. PMID 20554950.

- ↑ Grundy, SM; Balady, GJ; Criqui, MH; Fletcher, G; Greenland, P; Hiratzka, LF; และคณะ (May 1998). "Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: guidance from Framingham: a statement for healthcare professionals from the AHA Task Force on Risk Reduction. American Heart Association". Circulation. 97 (18): 1876–1887. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.97.18.1876. PMID 9603549.

- ↑ Shields, C; Shields, J (2008). Eyelid, conjunctival, and orbital tumors: atlas and textbook. Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7578-6.

- ↑ Zech, LA; Hoeg, JM (March 2008). "Correlating corneal arcus with atherosclerosis in familial hypercholesterolemia". Lipids in Health and Disease. 7 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-7-7. PMC 2279133. PMID 18331643.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 James, WD; Berger, TG (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. pp. 530–32. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ Rapini, RP; Bolognia, JL; Jorizzo, JL (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby. pp. 1415–16. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ Calderon, R; Schneider, RH; Alexander, CN; Myers, HF; Nidich, SI; Haney, C (1999). "Stress, stress reduction and hypercholesterolemia in African Americans: a review". Ethnicity & Disease. 9 (3): 451–62. PMID 10600068.

- ↑ Hawkley, LC; Cacioppo, JT (October 2010). "Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 40 (2): 218–227. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. PMC 3874845. PMID 20652462.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Mannu, GS; Zaman, MJ; Gupta, A; Rehman, HU; Myint, PK (February 2013). "Evidence of lifestyle modification in the management of hypercholesterolemia". Current Cardiology Reviews. 9 (1): 2–14. doi:10.2174/157340313805076313. PMC 3584303. PMID 22998604.

- ↑ Howell, WH; McNamara, DJ; Tosca, MA; Smith, BT; Gaines, JA (June 1997). "Plasma lipid and lipoprotein responses to dietary fat and cholesterol: a meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 65 (6): 1747–1764. doi:10.1093/ajcn/65.6.1747. PMID 9174470.

- ↑ DiNicolantonio, JJ; Lucan, SC; O'Keefe, JH (2016). "The Evidence for Saturated Fat and for Sugar Related to Coronary Heart Disease". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 58 (5): 464–472. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2015.11.006. PMC 4856550. PMID 26586275.

- ↑ Ascherio, A; Willett, WC (October 1997). "Health effects of trans fatty acids". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 66 (4 Suppl): 1006S–1010S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/66.4.1006S. PMID 9322581.

- ↑ Grundy, SM (November 2016). "Does Dietary Cholesterol Matter?". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 18 (11): 68. doi:10.1007/s11883-016-0615-0. PMID 27739004. S2CID 30969287.

- ↑ Vincent, MJ; Allen, B; Palacios, OM; Haber, LT; Maki, KC (January 2019). "Meta-regression analysis of the effects of dietary cholesterol intake on LDL and HDL cholesterol". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 109 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqy273. PMID 30596814.

- ↑ Herink, M; Ito, MK (2000-01-01). "Medication Induced Changes in Lipid and Lipoproteins". ใน De Groot, LJ; Chrousos, G; Dungan, K; Feingold, KR; Grossman, A; Hershman, JM; Koch, C; Korbonits, M; McLachlan, R (บ.ก.). Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. PMID 26561699.

- ↑ "Hypercholesterolemia". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Institutes of Health. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2013-12-05.

- ↑ Akioyamen, LE; Genest, J; Shan, SD; Reel, RL; Albaum, JM; Chu, A; Tu, JV (September 2017). "Estimating the prevalence of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 7 (9): e016461. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016461. PMC 5588988. PMID 28864697.

- ↑ Slatkin, M (August 2004). "A Population-Genetic Test of Founder Effects and Implications for Ashkenazi Jewish Diseases". Am. J. Hum. Genet. American Society of Human Genetics via PubMed. 75 (2): 282–93. doi:10.1086/423146. PMC 1216062. PMID 15208782.

- ↑ Durst, Ronen; Colombo, Roberto; Shpitzen, Shoshi; Avi, Liat Ben; และคณะ (2001). "Recent Origin and Spread of a Common Lithuanian Mutation, G197del LDLR, Causing Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Positive Selection Is Not Always Necessary to Account for Disease Incidence among Ashkenazi Jews". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (5): 1172–1188. doi:10.1086/320123. PMC 1226098. PMID 11309683.

- ↑ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 Consumer Reports; Drug Effectiveness Review Project (March 2013). "Evaluating statin drugs to treat High Cholesterol and Heart Disease: Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF). Best Buy Drugs. Consumer Reports: 9. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2013-03-27. which cites

- United States Department of Health and Human Services; National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; National Institutes of Health (June 2005). "NHLBI, High Blood Cholesterol: What You Need to Know". nhlbi.nih.gov. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2013-04-01. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2013-03-27.

- ↑ "คอเลสเตอรอลและโรคหัวใจ". Bumrungrad International Hospital. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2023-09-30. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-16.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and treatment". Mayo Clinic. 2023-01-11. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2024-03-13. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-16.

- ↑ ATP III Guidelines At-A-Glance Quick Desk Reference, National Cholesterol Education Program. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- ↑

Davidson, Michael H.; Pradeep, Pallavi (2023-07-03). "Hormonal and Metabolic Disorders". MSD Manual Consumer Version. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2023-11-14. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-16.

Although there is no natural cutoff between normal and abnormal cholesterol levels, ...

- ↑

"What Your Cholesterol Levels Mean". www.heart.org. 2017-11-16. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2024-02-26. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-16.

While cholesterol levels above “normal ranges” are important in your overall cardiovascular risk, like HDL and LDL cholesterol levels, your total blood cholesterol level should be considered in context with your other known risk factors.

- ↑

Nantsupawat, Nopakoon; Booncharoen, Apaputch; Wisetborisut, Anawat; Jiraporncharoen, Wichuda; และคณะ (2019-01-26). "Appropriate Total cholesterol cut-offs for detection of abnormal LDL cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol among low cardiovascular risk population". Lipids in Health and Disease. 18: 28. doi:10.1186/s12944-019-0975-x. ISSN 1476-511X. PMC 6347761. PMID 30684968.

The current appropriate TC cutoff to determine whether patients need further investigation and assessment is between 200 and 240 mg/dL [1, 17, 18]. However, the appropriate cut-off point for the younger population who may have low cardiovascular risk have not been examined extensively in the literature. A recent study suggests that a TC cut of point of between 200 and 240 may not be appropriate in identifying high LDL-C levels in apparently healthy people.

- ↑ Peters, SA; Singhateh, Y; Mackay, D; Huxley, RR; Woodward, M (May 2016). "Total cholesterol as a risk factor for coronary heart disease and stroke in women compared with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Atherosclerosis. 248: 123–131. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.016. PMID 27016614.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 Reiner, Z; Catapano, AL; De Backer, G; Graham, I; Taskinen, MR; Wiklund, O; และคณะ (July 2011). "ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS)". European Heart Journal. 32 (14): 1769–1818. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158. PMID 21712404.

- ↑ Superko, H. Robert (2009-05-05). "Advanced Lipoprotein Testing and Subfractionation Are Clinically Useful". Circulation. 119 (17): 2383–2395. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.809582. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ "New Information on Accuracy of LDL-C Estimation". American College of Cardiology. 2020-03-20. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2023-12-06. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-16.

- ↑ "Friedewald equation for calculating VLDL and LDL - All About Cardiovascular System and Disorders". Johnson's Techworld - Reliving my hobbies. 2017-11-04. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2023-09-28. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-16.

- ↑ Friedewald, WT; Levy, RI; Fredrickson, DS (June 1972). "Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge". Clinical Chemistry. 18 (6): 499–502. doi:10.1093/clinchem/18.6.499. PMID 4337382.

- ↑ Ison, HE; Clarke, SL; Knowles, JW (1993). "Familial Hypercholesterolemia". ใน Adam, MP; Ardinger, HH; Pagon, RA; Wallace, SE (บ.ก.). GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 24404629. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2021-01-04.

- ↑ U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. "Screening for Lipid Disorders: Recommendations and Rationale". คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2015-02-10. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2010-11-04.

- ↑

Chou, R; Dana, T; Blazina, I; Daeges, M; Bougatsos, C; Jeanne, TL (October 2016). "Screening for Dyslipidemia in Younger Adults: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine. 165 (8): 560–564. doi:10.7326/M16-0946. PMID 27538032. S2CID 20592431.

{{cite journal}}:|display-authors=6ไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - ↑ Bibbins-Domingo, K; Grossman, DC; Curry, SJ; Davidson, KW; Epling, JW; García, FA; และคณะ (August 2016). "Screening for Lipid Disorders in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 316 (6): 625–633. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9852. PMID 27532917.

- ↑ Genest, J; Frohlich, J; Fodor, G; McPherson, R (October 2003). "Recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease: summary of the 2003 update". CMAJ. 169 (9): 921–924. PMC 219626. PMID 14581310.

- ↑ "Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report". Circulation. 106 (25): 3143–3421. December 2002. doi:10.1161/circ.106.25.3143. hdl:2027/uc1.c095473168. PMID 12485966.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=ไม่มี|last1=(help) - ↑ Spector, R; Snapinn, SM (2011). "Statins for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: the right dose". Pharmacology. 87 (1–2): 63–69. doi:10.1159/000322999. PMID 21228612.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Grundy, SM; Cleeman, JI; Merz, CN; Brewer, HB; Clark, LT; Hunninghake, DB; และคณะ (July 2004). "Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines". Circulation. 110 (2): 227–239. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000133317.49796.0e. PMID 15249516.

- ↑ Consumer Reports; Drug Effectiveness Review Project (March 2013). "Evaluating statin drugs to treat High Cholesterol and Heart Disease: Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF). Best Buy Drugs. Consumer Reports: 9. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2013-03-27.

- ↑ Bhattarai, N; Prevost, AT; Wright, AJ; Charlton, J; Rudisill, C; Gulliford, MC (December 2013). "Effectiveness of interventions to promote healthy diet in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMC Public Health. 13: 1203. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1203. PMC 3890643. PMID 24355095.

- ↑ Hartley, L; Igbinedion, E; Holmes, J; Flowers, N; Thorogood, M; Clarke, A; และคณะ (June 2013). "Increased consumption of fruit and vegetables for the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD009874. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009874.pub2. PMC 4176664. PMID 23736950.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Brownawell, AM; Falk, MC (June 2010). "Cholesterol: where science and public health policy intersect". Nutrition Reviews. 68 (6): 355–364. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00294.x. PMID 20536780.

- ↑ Berger, S; Raman, G; Vishwanathan, R; Jacques, PF; Johnson, EJ (August 2015). "Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 102 (2): 276–294. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.100305. PMID 26109578.

- ↑ Keys, A; Anderson, JT; Grande, F (July 1965). "Serum cholesterol response to changes in the diet: IV. Particular saturated fatty acids in the diet". Metabolism. 14 (7): 776–787. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(65)90004-1. PMID 25286466.

- ↑ "Ancel Keys, PhD (1904-2004)" (PDF). National Lipid Association. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2016-08-15.

- ↑ Marshall, Tom (2000-01-29). "Exploring a fiscal food policy: the case of diet and ischaemic heart disease". BMJ. 320 (7230): 301–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7230.301. PMC 1117490. PMID 10650031.

- ↑ Hegsted, DM; McGandy, RB; Myers, ML; Stare, FJ (November 1965). "Quantitative effects of dietary fat on serum cholesterol in man". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 17 (5): 281–295. doi:10.1093/ajcn/17.5.281. PMID 5846902.

- ↑ Hegsted, D. M.; Mcgandy, R. B.; Myers, M. L.; Stare, F. J. (1965-11-01). "Quantitative Effects of Dietary Fat on Serum Cholesterol in Man". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (ภาษาอังกฤษ). 17 (5): 281–295. doi:10.1093/ajcn/17.5.281. ISSN 0002-9165.

- ↑ Grundy, Sm; Denke, Ma (1990). "Dietary influences on serum lipids and lipoproteins". Journal of Lipid Research. 31 (7): 1149–1172. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)42625-2.

- ↑ "Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee" (PDF). health.gov. 2015. p. 17. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2016-05-16.

The 2015 DGAC will not bring forward this recommendation 644 because available evidence shows no appreciable relationship between consumption of dietary cholesterol and serum cholesterol, consistent with the conclusions of the AHA/ACC report.

- ↑ Hooper, L; Martin, N; Jimoh, OF; Kirk, C; Foster, E; Abdelhamid, AS (August 2020). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3. PMC 8092457. PMID 32827219.

- ↑ Chowdhury, R; Warnakula, S; Kunutsor, S; Crowe, F; Ward, HA; Johnson, L; และคณะ (March 2014). "Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 160 (6): 398–406. doi:10.7326/M13-1788. PMID 24723079.

- ↑ Schwingshackl, L; Hoffmann, G (December 2013). "Comparison of effects of long-term low-fat vs high-fat diets on blood lipid levels in overweight or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 113 (12): 1640–1661. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2013.07.010. PMID 24139973.

Including only hypocaloric diets, the effects of low-fat vs high-fat diets on total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels were abolished.

- ↑ Brown, L; Rosner, B; Willett, WW; Sacks, FM (January 1999). "Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 69 (1): 30–42. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.1.30. PMID 9925120.

- ↑ Hollænder, PL; Ross, AB; Kristensen, M (September 2015). "Whole-grain and blood lipid changes in apparently healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 102 (3): 556–572. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.109165. PMID 26269373.

- ↑ Schaefer, EJ; Gleason, JA; Dansinger, ML (June 2009). "Dietary fructose and glucose differentially affect lipid and glucose homeostasis". The Journal of Nutrition. 139 (6): 1257S–1262S. doi:10.3945/jn.108.098186. PMC 2682989. PMID 19403705.

- ↑ Grundy, SM; Stone, NJ; Bailey, AL; Beam, C; Birtcher, KK; Blumenthal, RS; และคณะ (June 2019). "2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 139 (25): e1082–e1143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625. PMC 7403606. PMID 30586774.

- ↑ Koskinas, KC; Siontis, GC; Piccolo, R; Mavridis, D; Räber, L; Mach, F; Windecker, S (April 2018). "Effect of statins and non-statin LDL-lowering medications on cardiovascular outcomes in secondary prevention: a meta-analysis of randomized trials". European Heart Journal. 39 (14): 1172–1180. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx566. PMID 29069377.

- ↑ Tonelli, M; Lloyd, A; Clement, F; Conly, J; Husereau, D; Hemmelgarn, B; และคณะ (November 2011). "Efficacy of statins for primary prevention in people at low cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis". CMAJ. 183 (16): E1189–E1202. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101280. PMC 3216447. PMID 21989464.

- ↑ Mills, EJ; Wu, P; Chong, G; Ghement, I; Singh, S; Akl, EA; และคณะ (February 2011). "Efficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170,255 patients from 76 randomized trials". QJM. 104 (2): 109–124. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcq165. PMID 20934984.

- ↑ Mihaylova, B; Emberson, J; Blackwell, L; Keech, A; Simes, J; Barnes, EH; และคณะ (August 2012). "The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials". Lancet. 380 (9841): 581–590. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5. PMC 3437972. PMID 22607822.

- ↑ Chou, R; Dana, T; Blazina, I; Daeges, M; Jeanne, TL (November 2016). "Statins for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force". JAMA. 316 (19): 2008–2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15629. PMID 27838722.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Taylor, F; Huffman, MD; Macedo, AF; Moore, TH; Burke, M; G, Davey Smith; และคณะ (January 2013). "Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (1): CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004816.pub5. PMC 6481400. PMID 23440795.

- ↑ Pisaniello, AD; Scherer, DJ; Kataoka, Y; Nicholls, SJ (February 2015). "Ongoing challenges for pharmacotherapy for dyslipidemia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 16 (3): 347–356. doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.986094. PMID 25476544. S2CID 539314.

- ↑ Lebenthal, Y; Horvath, A; Dziechciarz, P; Szajewska, H; Shamir, R (September 2010). "Are treatment targets for hypercholesterolemia evidence based? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 95 (9): 673–680. doi:10.1136/adc.2008.157024. PMID 20515970. S2CID 24263653.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 67: Lipid modification. London, 2008.

- ↑ "แนวทางเวชปฏิบัตการใช้ยารักษาภาวะไขมันผิดปกติเพื่อป้องกันโรคหัวใจและหลอดเลือด พ.ศ. ๒๕๕๙" (PDF). เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2023-03-03. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-18.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 81.3 AMDA - The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (February 2014), "Ten Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, AMDA - The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, สืบค้นเมื่อ 2015-04-20

- ↑ Snow, V; Aronson, MD; Hornbake, ER; Mottur-Pilson, C; Weiss, KB (April 2004). "Lipid control in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 140 (8): 644–649. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00012. PMID 15096336. S2CID 6744974.

- ↑ Vijan, S; Hayward, RA (April 2004). "Pharmacologic lipid-lowering therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: background paper for the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 140 (8): 650–658. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00013. PMID 15096337. S2CID 25448635.

- ↑ Barnes, PM; Powell-Griner, E; McFann, K; Nahin, RL (May 2004). "Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002". Advance Data. 343 (343): 1–19. PMID 15188733.

- ↑ Liu, ZL; Liu, JP; Zhang, AL; Wu, Q; Ruan, Y; Lewith, G; Visconte, D (July 2011). "Chinese herbal medicines for hypercholesterolemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008305. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008305.pub2. PMC 3402023. PMID 21735427.

- ↑ Demonty, I; Ras, RT; van der Knaap, HC; Duchateau, GS; Meijer, L; Zock, PL; และคณะ (February 2009). "Continuous dose-response relationship of the LDL-cholesterol-lowering effect of phytosterol intake". The Journal of Nutrition. 139 (2): 271–284. doi:10.3945/jn.108.095125. PMID 19091798.

- ↑ Weingärtner, O; Böhm, M; Laufs, U (February 2009). "Controversial role of plant sterol esters in the management of hypercholesterolaemia". European Heart Journal. 30 (4): 404–409. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn580. PMC 2642922. PMID 19158117.

- ↑ Van Craeyveld, E; Jacobs, F; Gordts, SC; De Geest, B (2011). "Gene therapy for familial hypercholesterolemia". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 17 (24): 2575–2591. doi:10.2174/138161211797247550. PMID 21774774.

- ↑ Al-Allaf, FA; Coutelle, C; Waddington, SN; David, AL; Harbottle, R; Themis, M (December 2010). "LDLR-Gene therapy for familial hypercholesterolaemia: problems, progress, and perspectives". International Archives of Medicine. 3: 36. doi:10.1186/1755-7682-3-36. PMC 3016243. PMID 21144047.

แหล่งข้อมูลอื่น

| การจำแนกโรค | |

|---|---|

| ทรัพยากรภายนอก |