ฉบับร่าง:ประวัติของโทรทัศน์

| นี่คือบทความฉบับร่างซึ่งเปิดโอกาสให้ทุกคนสามารถแก้ไขได้ โปรดตรวจสอบว่าเนื้อหามีลักษณะเป็นสารานุกรมและมีความโดดเด่นควรแก่การรู้จักก่อนที่จะเผยแพร่เป็นบทความลงในวิกิพีเดีย กรุณาอดทนรอผู้เขียนคนอื่นมาช่วยตรวจให้ อย่าย้ายหน้าไปเป็นบทความเองโดยพลการ ค้นหาข้อมูล: Google (books · news · newspapers · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · NYT · TWL สำคัญ: ถ้าลบป้ายนี้ออกจะทำให้บันทึกหน้าไม่ได้ ผู้แก้ไขหน้านี้คนล่าสุด คือ JasperBot (พูดคุย | เรื่องที่เขียน) เมื่อ 36 วันก่อน (ล้างแคช) |

แนวคิดของโทรทัศน์เป็นผลงานของหลายบุคคลในช่วงปลายคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 19 และต้นคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 20 โดยมีรากฐานแรกเริ่มในช่วงคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 18 การส่งภาพเคลื่อนไหวผ่านระบบวิทยุในเชิงปฏิบัติครั้งแรก ใช้แผ่นเจาะรูแบบหมุนเพื่อกวาดภาพเป็นสัญญาณแปรผันตามเวลา ซึ่งสามารถสร้างขึ้นใหม่ได้ที่เครื่องรับกลับเป็นภาพประมาณของภาพต้นฉบับ การพัฒนาโทรทัศน์ถูกชะงักลงในช่วงสงครามโลกครั้งที่สอง หลังจากสิ้นสุดสงคราม วิธีการกวาดภาพและแสดงผลเป็นแบบอิเล็กทรอนิกส์ทั้งหมด ภาพกลายเป็นมาตรฐาน มาตรฐานต่าง ๆ หลายประการสำหรับการเพิ่มสีสันให้กับภาพที่ส่ง ได้รับการพัฒนาตามภูมิภาคต่าง ๆ โดยใช้มาตรฐานของสัญญาณที่เข้ากันไม่ได้ในทางเทคนิค การออกอากาศโทรทัศน์ได้ขยายตัวอย่างรวดเร็วหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่สอง กลายเป็นสื่อกลางที่สำคัญสำหรับการโฆษณา, การโฆษณาชวนเชื่อ และการบันเทิง[1]

การแพร่ภาพโทรทัศน์สามารถกระจายไปในอากาศโดยสัญญาณวิทยุผ่านระบบวีเอชเอฟ และยูเอชเอฟ จากสถานีส่งสัญญาณภาคพื้นดิน, โดยสัญญาณไมโครเวฟจากดาวเทียมที่โคจรรอบโลก หรือโดยการส่งผ่านสายไปยังผู้บริโภคแต่ละรายทางเคเบิลทีวี หลายประเทศได้เปลี่ยนผ่านวิธีการส่งสัญญาณแบบแอนะล็อกที่มีอยู่เดิม และได้ใช้มาตรฐานโทรทัศน์ระบบดิจิทัล โดยมีคุณสมบัติการทำงานเพิ่มเติม และรักษาความกว้างแถบความถี่วิทยุเพื่อการใช้งานที่ทำกำไรได้มากขึ้น นอกจากนี้ยังสามารถเผยแพร่รายการโทรทัศน์ผ่านทางอินเทอร์เน็ตได้อีกด้วย

การแพร่ภาพโทรทัศน์อาจได้รับรายได้จากการโฆษณา โดยองค์กรเอกชนหรือหน่วยงานของรัฐที่เตรียมการจัดจำหน่ายต้นทุน หรือในบางประเทศ โดยค่าธรรมเนียมใบอนุญาตรับชมโทรทัศน์ที่จ่ายโดยเจ้าของเครื่องรับ แต่บริการบางอย่าง โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งดำเนินการโดยเคเบิลหรือดาวเทียม จ่ายโดยวิธีการสมัครสมาชิก

การแพร่ภาพทางโทรทัศน์ได้รับการสนับสนุนการพัฒนาด้านเทคนิคอย่างต่อเนื่อง เช่น เครือข่ายไมโครเวฟระยะไกล ซึ่งช่วยให้สามารถกระจายรายการได้ทั่วพื้นที่ทางภูมิศาสตร์ที่กว้างขวาง วิธีการบันทึกภาพที่ช่วยให้สามารถแก้ไขโปรแกรมและเล่นซ้ำเพื่อใช้ในภายหลังได้ โทรทัศน์สามมิติถูกใช้ในเชิงพาณิชย์แต่ยังไม่ได้รับการยอมรับจากผู้บริโภคในวงกว้าง เนื่องมาจากข้อจำกัดของวิธีการแสดงผล

โทรทัศน์เครื่องกล

[แก้]การส่งโทรสารถือเป็นสิ่งบุกเบิกวิธีการแสดงภาพด้วยกลไกในช่วงต้นคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 19 อเล็กซานเดอร์ เบน นักประดิษฐ์ชาวสกอตได้แนะนำเครื่องโทรสารในช่วงปี ค.ศ. 1843–1846 ขณะที่ เฟรเดอริก เบคเวลล์ นักฟิสิกส์ชาวอังกฤษได้ทดลองในห้องปฏิบัติการเป็นผลสำเร็จในปี ค.ศ. 1851 ระบบโทรสารระบบแรกที่ใช้งานได้จริงซึ่งทำงานด้วยสายโทรเลข ได้รับการพัฒนาโดย โจวันนี กาเซลลี นักประดิษฐ์ชาวอิตาลี นับตั้งแต่ปี ค.ศ. 1856 เป็นต้นมา[2][3][4]

วิลลัฟบี สมิธ วิศวกรไฟฟ้าชาวอังกฤษ ค้นพบการนำแสงของธาตุซีลีเนียมในปี ค.ศ. 1873 สิ่งนี้นำไปสู่เทคโนโลยีอื่น ๆ ในการถ่ายภาพเทเลโฟโตกราฟฟี ซึ่งเป็นวิธีการส่งภาพนิ่งผ่านสายโทรศัพท์ ในช่วงต้นปี ค.ศ. 1895 ตลอดจนอุปกรณ์การสแกนภาพแบบอิเล็กทรอนิกส์ทุกประเภท ทั้งแบบนิ่งและแบบเคลื่อนที่ และในท้ายที่สุดไปยังกล้องโทรทัศน์

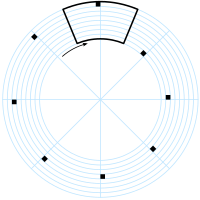

พอล ก็อตต์ลีบ นิปคอฟ นักศึกษามหาวิทยาลัยในเยอรมนีในวัย 23 ปี ได้เสนอและจดสิทธิบัตรดิสก์ของนิปคอฟในปี ค.ศ. 1884[5] This was a spinning disk with a spiral pattern of holes in it, so each hole scanned a line of the image. Although he never built a working model of the system, variations of Nipkow's spinning-disk "image rasterizer" became exceedingly common.[5] Constantin Perskyi had coined the word television in a paper read to the International Electricity Congress at the International World Fair in Paris on August 24, 1900. Perskyi's paper reviewed the existing electromechanical technologies, mentioning the work of Nipkow and others.[6] However, it was not until 1907 that developments in amplification tube technology, by Lee de Forest and Arthur Korn among others, made the design practical.[7]

The first demonstration of the instantaneous transmission of images was by Georges Rignoux and A. Fournier in Paris in 1909. A matrix of 64 selenium cells, individually wired to a mechanical commutator, served as an electronic retina. In the receiver, a type of Kerr cell modulated the light and a series of variously angled mirrors attached to the edge of a rotating disc scanned the modulated beam onto the display screen. A separate circuit regulated synchronization. The 8×8 pixel resolution in this proof-of-concept demonstration was just sufficient to clearly transmit individual letters of the alphabet. An updated image was transmitted "several times" each second.[8]

ในปี ค.ศ. 1911 Boris Rosing and his student Vladimir Zworykin created a system that used a mechanical mirror-drum scanner to transmit, in Zworykin's words, "very crude images" over wires to the "Braun tube" (cathode ray tube or "CRT") in the receiver. Moving images were not possible because, in the scanner, "the sensitivity was not enough and the selenium cell was very laggy".[9]

เดือนพฤษภาคม ค.ศ. 1914 Archibald Low gave the first demonstration of his television system at the Institute of Automobile Engineers in London. He called his system 'Televista'. The events were widely reported worldwide and were generally entitled Seeing By Wireless. The demonstrations had so impressed Harry Gordon Selfridge that he included Televista in his 1914 Scientific and Electrical Exhibition at his store.[10][11] It also interested Deputy Consul General Carl Raymond Loop who filled a US consular report from London containing considerable detail about Low's system.[12] Low's invention employed a matrix detector (camera) and a mosaic screen (receiver/viewer) with an electro-mechanical scanning mechanism that moved a rotating roller over the cell contacts providing a multiplex signal to the camera/viewer data link. The receiver employed a similar roller. The two rollers were synchronised. Hence, it was unlike any of the intervening TV systems of the 20th Century and in many respects, Low had a digital TV system 80 years before the advent of today's digital TV. World War One shortly after these demonstrations in London and Low became involved in sensitive military work. He did not apply for his "Televista" Patent No. 191,405 titled "Improved Apparatus for the Electrical Transmission of Optical Images" until 1917. The patent release was delayed (possibly for security reasons). ในที่สุดก็ได้รับการตีพิมพ์ในปี ค.ศ. 1923 From the patent, we know that the scanning roller had a row of conductive contacts corresponding to the cells in each row of the array and arranged to sample each cell in turn as the roller rotated. The receivers roller was similarly constructed and each revolution addressed a row of cells as the rollers traversed over their array of cells. Loops report tells us that... "The roller is driven by a motor of 3,000 revolutions per minute, and the resulting variations of light are transmitted along an ordinary conducting wire."

The cell-matrix shown in the patent is 22×22 (approaching an impressive 500 cells/pixels) and each 'camera' cell had a corresponding 'viewer' cell. Loop said it was a "screen divided into a large number of small squares cells of selenium" and the patent states "into each... space I place a selenium cell". Low covered the cells with a liquid dielectric and the roller connected with each cell in turn through this medium as it rotated and travelled over the array. The receiver used bimetallic elements that acted as shutters "transmitting more or less light according to the current passing through them..." as stated in the patent. Low said the main deficiency of the system was the selenium cells used for converting light waves into electric impulses, which responded too slowly thus spoiling the effect. Loop reported that "The system has been tested through a resistance equivalent to a distance of four miles, but in the opinion of Doctor Low there is no reason why it should not be equally effective over far greater distances. The patent states that this connection could be either wired or wireless. The cost of the apparatus is considerable because the conductive sections of the roller are made of platinum..."

ปี ค.ศ. 1914 the demonstrations certainly garnered a lot of media interest with The Times reporting on 30 May:

| “ | An inventor, Dr. A. M. Low, has discovered a means of transmitting visual images by wire. If all goes well with this invention, we shall soon be able, it seems, to see people at a distance. | ” |

วันที่ 29 พฤษภาคม Daily Chronicle รายงานว่า

| “ | Dr. Low gave a demonstration for the first time in public, with a new apparatus that he has invented, for seeing, he claims by electricity, by which it is possible for persons using a telephone to see each other at the same time | ” |

ในปี ค.ศ. 1927 Ronald Frank Tiltman asked Low to write the introduction to his book in which he acknowledged Low's work, referring to Low's various related patents with an apology that they were of 'too technical a nature for inclusion'.[13] Later in his 1938 patent Low envisioned a much larger 'camera' cell density achieved by a deposition process of caesium alloy on an insulated substrate that was subsequently sectioned to divide it into cells, the essence of today's technology. Low's system failed for various reasons, mostly due to its inability to reproduce an image by reflected light and simultaneously depict gradations of light and shade. It can be added to the list of systems, like that of Boris Rosing, that predominantly reproduced shadows. With subsequent technological advances, many such ideas could be made viable decades later, but at the time they were impractical.

ในปี ค.ศ. 1923 Scottish inventor John Logie Baird envisaged a complete television system that employed the Nipkow disk. Nipkow's was an obscure, forgotten patent and not at all obvious at the time. He created his first prototypes in Hastings, where he was recovering from a serious illness. In late 1924, Baird returned to London to continue his experiments there. On March 25, 1925, Baird gave the first public demonstration of televised silhouette images in motion, at Selfridge's Department Store in London.[14] Since human faces had inadequate contrast to show up on his system at this time, he televised cut-outs and by mid-1925 the head of a ventriloquist's dummy he later named "Stooky Bill", whose face was painted to highlight its contrast. "Stooky Bill" also did not complain about the long hours of staying still in front of the blinding level of light used in these experiments. On October 2, 1925, suddenly the dummy's head came through on the screen with incredible clarity. On January 26, 1926, he demonstrated the transmission of images of real human faces for 40 distinguished scientists of the Royal Institution. This is widely regarded as being the world's first public television demonstration. Baird's system used Nipkow disks for both scanning the image and displaying it. A brightly illuminated subject was placed in front of a spinning Nipkow disk set with lenses that swept images across a static photocell. At this time, it is believed that it was a thallium sulphide (Thalofide) cell, developed by Theodore Case in the US, that detected the light reflected from the subject. This was transmitted by radio to a receiver unit, where the video signal was applied to a neon bulb behind a similar Nipkow disk synchronised with the first. The brightness of the neon lamp was varied in proportion to the brightness of each spot on the image. As each lens in the disk passed by, one scan line of the image was reproduced. With this early apparatus, Baird's disks had 16 lenses, yet in conjunction with the other discs used produced moving images with 32 scan-lines, just enough to recognize a human face. He began with a frame-rate of five per second, which was soon increased to a rate of 1212 frames per second and 30 scan-lines.

ในปี ค.ศ. 1927 Baird transmitted a signal over 438 ไมล์ (705 กิโลเมตร) of telephone line between London and Glasgow. In 1928, Baird's company (Baird Television Development Company/Cinema Television) broadcast the first transatlantic television signal, between London and New York, and the first shore-to-ship transmission. In 1929, he became involved in the first experimental mechanical television service in Germany. In November of the same year, Baird and Bernard Natan of Pathé established France's first television company, Télévision-Baird-Natan. In 1931, he made the first outdoor remote broadcast, of the Derby.[15] In 1932, he demonstrated ultra-short wave television. Baird Television Limited's mechanical systems reached a peak of 240 lines of resolution at the company's Crystal Palace studios, and later on BBC television broadcasts in 1936, though for action shots (as opposed to a seated presenter) the mechanical system did not scan the televised scene directly. Instead, a 17.5mm film was shot, rapidly developed, and then scanned while the film was still wet.

ความสำเร็จของบริษัทสโคโพนี (อังกฤษ: Scophony) กับระบบกลไกในช่วงทศวรรษที่ 1930 ทำให้สามารถดำเนินงานไปยังสหรัฐได้เมื่อถูกลดทอนธุรกิจในอังกฤษในช่วงสงครามโลกครั้งที่สอง

ชาร์ลส์ ฟรานซิส เจนกินส์ นักประดิษฐ์ชาวอเมริกัน นับเป็นผู้บุกเบิกโทรทัศน์ด้วย He published an article on "Motion Pictures by Wireless" in 1913, but it was not until December 1923 that he transmitted moving silhouette images for witnesses. On June 13, 1925, Jenkins publicly demonstrated the synchronized transmission of silhouette pictures. In 1925, Jenkins used a Nipkow disk and transmitted the silhouette image of a toy windmill in motion, over a distance of five miles (from a naval radio station in Maryland to his laboratory in Washington, D.C.), using a lensed disk scanner with a 48-line resolution.[16][17] He was granted U.S. patent 1,544,156 (Transmitting Pictures over Wireless) on June 30, 1925 (filed March 13, 1922).[18]

วันที่ 25 ธันวาคม ค.ศ. 1926 เคนจิโร ทากายานางิ demonstrated a television system with a 40-line resolution that employed a Nipkow disk scanner and CRT display at Hamamatsu Industrial High School in Japan. This prototype is still on display at the Takayanagi Memorial Museum at Shizuoka University, Hamamatsu Campus.[19] By 1927, Takayanagi improved the resolution to 100 lines, which was not surpassed until 1931.[20] By 1928, he was the first to transmit human faces in halftones. His work had an influence on the later work of Vladimir K. Zworykin.[21] In Japan he is viewed as the man who completed the first all-electronic television.[22] His research toward creating a production model was halted by the US after Japan lost World War II.[19]

ในปี ค.ศ. 1927 ทีมจากห้องปฏิบัติการของโทรศัพท์เบลล์ demonstrated television transmission from Washington to New York, using a prototype flat panel plasma display to make the images visible to an audience.[23] The monochrome display measured two feet by three feet and had 2500 pixels.

เฮอร์เบิร์ต อี. ไอเวส และ แฟรนก์ เกรย์ จากห้องปฏิบัติการของโทรศัพท์เบลล์ gave a dramatic demonstration of mechanical television on April 7, 1927. The reflected-light television system included both small and large viewing screens. The small receiver had a two-inch-wide by 2.5-inch-high screen. The large receiver had a screen 24 inches wide by 30 inches high. Both sets were capable of reproducing reasonably accurate, monochromatic moving images. Along with the pictures, the sets also received synchronized sound. The system transmitted images over two paths: first, a copper wire link from Washington to New York City, then a radio link from Whippany, New Jersey. Comparing the two transmission methods, viewers noted no difference in quality. Subjects of the telecast included Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. A flying-spot scanner beam illuminated these subjects. The scanner that produced the beam had a 50-aperture disk. The disc revolved at a rate of 18 frames per second, capturing one frame about every 56 milliseconds. (Today's systems typically transmit 30 or 60 frames per second, or one frame every 33.3 or 16.7 milliseconds respectively.) Television historian Albert Abramson underscored the significance of the Bell Labs demonstration: "It was in fact the best demonstration of a mechanical television system ever made to this time. It would be several years before any other system could even begin to compare with it in picture quality."[24]

ในปี ค.ศ. 1928 ดับเบิลยูอาร์จีบี (เดิมชื่อ ดับเบิลยูทูเอกซ์บี) ได้เริ่มต้นขึ้นในฐานะสถานีโทรทัศน์แห่งแรกของโลก ออกอากาศจากโรงงานของเจเนอรัลอิเล็กทริก ในเมืองสเกอเนคเทอดี รัฐนิวยอร์ก เป็นที่รู้จักอย่างแพร่หลายในชื่อ "ดับเบิลยูจีวายเทเลวิชัน"

ขณะเดียวกันในสหภาพโซเวียต เลออง เทอเรอมิน had been developing a mirror drum-based television, starting with 16-line resolution in 1925, then 32 lines and eventually 64 using interlacing in 1926. As part of his thesis on May 7, 1926, Theremin electrically transmitted and then projected near-simultaneous moving images on a five-foot square screen.[17] By 1927 he achieved an image of 100 lines, a resolution that was not surpassed until 1931 by RCA, with 120 lines.[ต้องการอ้างอิง]

Because only a limited number of holes could be made in the disks, and disks beyond a certain diameter became impractical, image resolution in mechanical television broadcasts was relatively low, ranging from about 30 lines up to about 120. Nevertheless, the image quality of 30-line transmissions steadily improved with technical advances, and by 1933 the UK broadcasts using the Baird system were remarkably clear.[25] A few systems ranging into the 200-line region also went on the air. Two of these were the 180-line system that Compagnie des Compteurs (CDC) installed in Paris in 1935, and the 180-line system that Peck Television Corp. started in 1935 at station VE9AK in Montreal.[26][27]

อันทวน โกเดลลี (22 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 1875 – 28 เมษายน ค.ศ. 1954) ขุนนางชาวสโลเวเนีย เป็นนักประดิษฐ์ผู้หลงใหล Among other things, he had devised a miniature refrigerator for cars and a new rotary engine design. Intrigued by television, he decided to apply his technical skills to the new medium. At the time, the biggest challenge in television technology was to transmit images with sufficient resolution to reproduce recognizable figures. As recounted by media historian Melita Zajc, most inventors were determined to increase the number of lines used by their systems – some were approaching what was then the magic number of 100 lines. But Baron Codelli had a different idea. In 1929, he developed a television device with a single line – but one that formed a continuous spiral on the screen. Codelli based his ingenious design on his understanding of the human eye. He knew that objects seen in peripheral vision don't need to be as sharp as those in the center. The baron's mechanical television system, whose image was sharpest in the middle, worked well, and he was soon able to transmit images of his wife, Ilona von Drasche-Lazar, over the air. Despite the backing of the German electronics giant Telefunken, however, Codelli's television system never became a commercial reality. Electronic television ultimately emerged as the dominant system, and Codelli moved on to other projects. His invention was largely forgotten.[28][29]

ความก้าวหน้าของโทรทัศน์ระบบอิเล็กทรอนิกส์ทั้งหมด (รวมถึงเครื่องแยกภาพและหลอดกล้องอื่น ๆ และหลอดรังสีแคโทดสำหรับเครื่องผลิตซ้ำ) ถือเป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของจุดจบของระบบเครื่องกลในฐานะรูปแบบที่โดดเด่นของโทรทัศน์ โทรทัศน์ระบบเครื่องกลมักจะสร้างภาพขนาดเล็กเท่านั้น เป็นโทรทัศน์ประเภทหลักจนถึงปี ค.ศ. 1930 การออกอากาศทางโทรทัศน์ด้วยระบบเครื่องกลสิ้นสุดลงในปีในปี ค.ศ. 1939 ที่สถานีที่ดำเนินการโดยมหาวิทยาลัยของรัฐจำนวนหนึ่งในสหรัฐ

อ้างอิง

[แก้]- ↑ Stephens, Mitchell (February 6, 2015). "History of Television". www.nyu.edu. New York University. สืบค้นเมื่อ February 6, 2015.

- ↑ Huurdeman, p. 149 The first telefax machine to be used in practical operation was invented by an Italian priest and professor of physics, Giovanni Caselli (1815–1891).

- ↑ Beyer, p. 100 The telegraph was the hot new technology of the moment, and Caselli wondered if it was possible to send pictures over telegraph wires. He went to work in 1855, and over the course of six years perfected what he called the "pantelegraph." It was the world's first practical fax machine.

- ↑ "Giovanni Caselli". คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ มกราคม 15, 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Shiers & Shiers (1997), pp. 13, 22

- ↑ Perskyi, Constantin (18–25 August 1900). Télévision au moyen de l'électricité. Congrès international d'électricité (ภาษาฝรั่งเศส). Paris.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: date format (ลิงก์) - ↑ "Sending Photographs by Telegraph", The New York Times, Sunday Magazine, September 20, 1907, p. 7.

- ↑ de Varigny, Henry (December 11, 1909). La vision à distance (ภาษาฝรั่งเศส). Paris: L'Illustration. p. 451. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ March 3, 2016.

- ↑ Burns (1998), p. 119

- ↑ Bloom, Ursula (1958). He Lit The Lamp: A Biography Of Professor A. M. Low. Burke.

- ↑ Maloney, Alison (2014). The World of Mr Selfridge: The Official Companion to the Hit ITV Series. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-3885-0.

- ↑ Mills, Steve (2019). The Dawn of the Drone. Casemate Publishers.

- ↑ Tiltman, Ronald Frank (1927). Television for the Home. Hutchinson.

- ↑ "Current Topics and Events". Nature. 115 (2, 892): 504–508. 1925. Bibcode:1925Natur.115..504.. doi:10.1038/115504a0.

- ↑ Baird, J. L. (1933). "Television in 1932". BBC Annual Report 1933.

- ↑ "Radio Shows Far Away Objects in Motion". The New York Times. June 14, 1925. p. 1.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Glinsky, Albert (2000). Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 41–45. ISBN 978-0-252-02582-2.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 1,544,156

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kenjiro Takayanagi: The Father of Japanese Television, NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation), 2002, retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ↑ High Above: The untold story of Astra, Europe's leading satellite company, page 220, Springer Science+Business Media

- ↑ Abramson, Albert (1995). Zworykin, Pioneer of Television. University of Illinois Press. p. 231. ISBN 0-252-02104-5.

- ↑ "TV's Japanese Dad?". Popular Photography. November 1990. p. 5.

- ↑ "Television Demonstration in America" (PDF). The Wireless World and Radio Review. Vol. 20 no. 22. London. June 1, 1927. pp. 680–686.

- ↑ Abramson (1987), p. 101

- ↑ McLean, Donald F. (2000). Restoring Baird's Image. London: IEEE. p. 184.

- ↑ "VE9AK". Earlytelevision.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2010-03-02.

- ↑ "Peck Television Corporation Console Receiver and Camera". Early Television Museum. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Codelli, Anton. Early Television: A Bibliographic Guide to 1940. p. 192. article 1,898.

- ↑ Culture.si: http://www.culture.si/en/Radio-Television_Slovenia_(RTV_Slovenia), The first known transmitted TV image on the territory of Slovenia