กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือและกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้

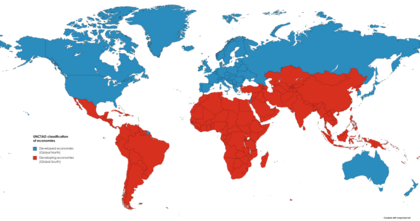

กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือและกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้เป็นคำที่ใช้เรียกวิธีในการจัดกลุ่มประเทศด้วยลักษณะสำคัญทางเศรษฐกิจสังคมและการเมืองระหว่างประเทศ ตามนิยามของการประชุมสหประชาชาติว่าด้วยการค้าและการพัฒนา (อังค์ถัด) กลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้ ประกอบไปด้วย แอฟริกา ลาตินอเมริกาและแคริเบียน เอเชีย (ยกเว้น อิสราเอล ญี่ปุ่น และ เกาหลีใต้) และ โอเชียเนีย (ยกเว้น ออสเตรเลีย และ นิวซีแลนด์)[1][2][a] กลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้ส่วนใหญ่มักจะยังขาดมาตรฐานการครองชีพ ซึ่งประกอบไปด้วยรายได้ที่ต่ำ ระดับความยากจนสูง อัตราการเพิ่มของประชากรสูง ที่อยู่อาศัยไม่พอเพียง โอกาสทางการศึกษาที่จำกัด และระบบสุขภาพที่ไม่สมบูรณ์ เป็นต้น[b] นอกจากนี้ เมืองในประเทศเหล่านี้ยังมีโครงสร้างพื้นฐานที่อ่อนแอ[c] คำตรงข้ามของกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้ คือ กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือ อังค์ถัดได้ให้นิยามโดยกว้างไว้ว่าประกอบไปด้วย อเมริกาเหนือและยุโรป อิสราเอล ญี่ปุ่น เกาหลีใต้ ออสเตรเลีย และนิวซีแลนด์[1][2][a] ดังนั้น คำทั้งสองมิได้หมายความถึงซีกโลกเหนือและซีกโลกใต้ แต่มีที่มาเนื่องจากประเทศส่วนใหญ่ของกล่มประเทศโลกเหนือและกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้อยู่ในซีกโลกทั้งสองทางภูมิศาสตร์[3]

สำหรับนิยามอย่างจำเพาะเจาะจง กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือประกอบไปด้วยประเทศพัฒนาแล้ว ในขณะที่กลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้ประกอบไปด้วยประเทศกำลังพัฒนาและประเทศพัฒนาน้อยที่สุด[2][4] การจัดกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้โดยองค์กรภาครัฐและองค์กรเพื่อการพัฒนาเกิดขึ้นเพื่อทดแทนคำ "โลกที่สาม" โดยเพื่อว่าเป็นคำที่เปิดกว้างและไม่ยึดโยงกับค่านิยมใด[5] ซึ่งอาจรวมไปถึงคำว่า "พัฒนาแล้ว" และ "กำลังพัฒนา" ประเทศในกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้เคยถูกเรียกว่าประเทศอุตสาหกรรมใหม่หรือประเทศที่กำลังเข้ากระบวนการอุตสาหกรรม ซึ่งหลายประเทศเหล่านี้เคยเป็นหรือยังอยู่ภายใต้อาณานิคม[6]

กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือและกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้มักถูกนิยามด้วยความแตกต่างกันในเชิงของความมั่งคั่ง การพัฒนาทางทางเศรษฐกิจ ความเหลื่อมล้ำของรายได้ และ ดัชนีความแข็งแกร่งของประชาธิปไตย รวมถึงเสรีภาพทางการเมือลและเสรีภาพทางเศรษฐกิจซึ่งมีดัชนีชี้วัดหลายตัวที่เกี่ยวข้อง กลุ่มประเทศซีกโลกเหนือมักจะมีความมั่งคั่งที่มากกว่า ความเหลื่อมล้ำที่น้อยกว่า มีความเป็นประชาธิปไตยมากกว่า มีสันติภาพมากกว่า และสามารถส่งออกผลิตภัณฑ์อันเกิดจากความก้าวหน้าทางเทคโนโลยีได้ เป็นต้น ในทางตรงข้าม กลุ่มประเทศซีกโลกใต้มักจะยากจนกว่า มีความเหลื่อมล้ำที่มากกว่า มีความเป็นประชาธิปไตยน้อยกว่า ไม่ค่อยสงบสุข และยังพึ่งพาเกษตรกรรมเป็นกิจกรรมหลักทางเศรษฐกิจ[d] นักวิชาการบางกลุ่มเห็นว่าช่องว่างระหว่างกลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือและกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้กำลังแคบลงด้วยกระบวนการโลกาภิวัฒน์[7] นักวิชาการอีกกลุ่มไม่เชื่อความเห็นนี้ โดยเชื่อว่ากลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้กลับยากจนลงเมื่อเทียบกับกลุ่มประเทศโลกเหลือในช่วงเวลาเดียวกัน[8][9][10]

นับแต่สงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 มีความร่วมมือในเป็นปรากฎการณ์ใหม่เรียกว่า “South–South cooperation” (SSC) ในกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้เพื่อท้าทายกล่มประเทศโลกเหนือที่ผูกขาดความเป็นหนึ่งด้านการเมืองและเศรษฐกิจ [11][12][13] ปรากฎการณ์เหล่านี้โด่งดังภายใต้บริบทของการย้ายฐานการผลิตจากกลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือไปยังกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้[13] และมีอิทธิพลต่อนโยบายทางการทูตของประเทศมหาอำนาจในกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้ เช่น สาธารณรัฐประชาชนจีน[13] ดังนั้น แนวโน้มเศรษฐกิจสมัยใหม่ได้เพิ่มศักยภาพในการเติมโตทางเศรษฐกิจและการก้าวสู่อุตสาหกรรมของกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้ ภายใต้ความพยายามดำเนินการอย่างมุ่งเป้าในรูปแบบ SSC เพื่อผ่อนคลายการกดขึ่ที่มีมาแต่ยุคอาณานิคม และก้าวข้ามเส้นแบ่งทางการเมืองของภูมิศาสตร์ของเศรษฐกิจและการเมืองยุคหลังสงคราม อันเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของกระบวนการปลดแอกจากอาณานิคม[14]

นิยาม[แก้]

| 0.800–1.000 (สูงมาก) 0.700–0.799 (สูง) 0.550–0.699 (ปานกลาง) | 0.350–0.549 (ต่ำ) ไม่มีข้อมูล |

กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือและกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้มิได้นิยามโดยภูมิศาสตร์และไม่ใช้การแบ่งด้วยเส้นศูนย์สูตรเพื่อแบ่งความรวยความจนออกจากกัน[3] ภูมิศาสตร์ในบริบทนี้หมายถึงเศรษฐกิจและการโยกย้าย ซึ่งอยู่ภายใต้โลกาภิวัฒน์และทุนนิยมสากล[3]

โดยทั่วไป กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหนือและกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้มิได้หมายถึงซีกโลกเหนือและซิกโลกใต้[3] กลุ่มประเทศโลกเหลือประกอบไปด้วยอเมริกาเหนือ ยุโรป อิสราเอล ญี่ปุ่น เกาหลีใต้ ออสเตรเลีย และนิวซีแลนด์ ตามนิยามของอังค์ถัด[1][2][a] กลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้ประกอบไปด้วยแอฟริกา ลาตินอเมริกาและแคริเบียน เอเชีย ยกเว้นอิสราเอล ญี่ปุ่น เกาหลีใต้ และโอเชียเนีย ยกเว้น ออสเตรเลียและนิวซีแลนด์ ตามนิยามของอังค์ถัดเช่นกัน[1][2][a] นักวิชาการบางคน เช่น นักสังคมวิทยาชาวออสเตรเลีย Fran Collyer และ Raewyn Connell ตั้งของสังเกตว่าออสเตรเลียและนิวซีแลนด์ถูกแบ่งแยกกีดกันเช่นเดียวกับกลุ่มประเทศโลกใต้เพราะว่าความโดดเดี่ยวทางภูมิศาสตร์และการต้งอยู่ในซีกโลกใต้[15][16]

เชิงอรรถ[แก้]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Although Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore and Taiwan have very-high Human Development Indices and are classified as advanced economies by the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development classifies them as the Global South. Also, Singapore is the one of Small Island Developing States.

- ↑

- Thomas-Slayter, Barbara P. (2003). Southern Exposure: International Development and the Global South in the Twenty-First Century. United States: Kumarian Press. p. 9-10. ISBN 978-1-56549-174-8.

among the countries of the Global South, there are also some common characteristics. First and foremost is a continuing struggle for secure livelihoods amidst conditions of serious poverty for a large number of people in these nations. For many, incomes are low, access to resources is limited, housing is inadequate, health is poor, educational opportunities are insufficient, and there are high infant mortality rates along with low life expectancy. ... In addition to the attributes associated with a low standard of living, several other characteristics are common to the Global South. One is the high rate of population growth and a consequent high dependency burden — that is, the responsibility for dependents, largely young children. In many countries almost half the population is under fifteen years old. This population composition represents not only a significant responsibility, but in the immediate future, it creates demands on services for schools, transport, new jobs, and related infrastructure. If a nation’s gross national income (GNI) is growing at 2 percent a year and its population is growing at that rate too, then any gains are wiped out.

- Speth, James Gustave; Haas, Peter (2013). Global Environmental Governance: Foundations of Contemporary Environmental Studies. Island Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-59726-605-5.

Poverty, lower life expectancies, illiteracy, lack of basic health amenities, and high population growth rates meant that national priorities in these countries were firmly oriented toward economic and social objectives.The global “South,” as these nations came to be known, considered their development priorities to be imperative; they wanted to “catch up” with the richer nations.They also asserted that the responsibility of protecting the environment was primarily on the shoulders of the richer “Northern” nations

- Thomas-Slayter, Barbara P. (2003). Southern Exposure: International Development and the Global South in the Twenty-First Century. United States: Kumarian Press. p. 9-10. ISBN 978-1-56549-174-8.

- ↑

- Graham, Stephen (2010). Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-135-85199-6.

In much debate on cities in the Global South, infrastructure is synonymous with breakdown, failure, interruption, and improvisation. The categorization of poorer cities through a lens of developmentalism has often meant that they are constructed as “problem.” These are cities, as Anjaria has argued, discursively exemplified by their crowds, their dilapidated buildings, and their “slums.”

- Adey, Peter; Bissell, David; Hannam, Kevin; Merriman, Peter; Sheller, Mimi, บ.ก. (2014). The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities. Routledge. p. 470. ISBN 978-1-317-93413-4.

In many global south cities, for example, access to networked infrastructures has always been highly fragmented, highly unreliable and problematic, even for relatively wealthy or powerful groups and neighbourhoods. In contemporary Mumbai, for example, many upper-middle-class residents have to deal with water or power supplies which operate for only a few hours per day. Their efforts to move into gated communities are often motivated as much by their desires for continuous power and water supplies as by hopes for better security.

- Lynch, Andrew P. (2018). Global Catholicism in the Twenty-first Century. Springer Singapore. p. 9. ISBN 978-981-10-7802-6.

The global south remains very poor relative to the north, and many countries continue to lack critical infrastructure and social services in health and education. Also, a great deal of political instability and violence inhibits many nations in the global south.

- Graham, Stephen (2010). Disrupted Cities: When Infrastructure Fails. Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-135-85199-6.

- ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อagri

อ้างอิง[แก้]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "UNCTADstat - Classifications". United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

The developing economies broadly comprise Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia without Israel, Japan, and the Republic of Korea, and Oceania without Australia and New Zealand. The developed economies broadly comprise Northern America and Europe, Israel, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Handbook of Statistics 2022" (PDF) (ภาษาอังกฤษ). unctad.org. p. 21. เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2022-12-12.

Note: North refers to developed economies, South to developing economies; trade is measured from the export side; deliveries to ship stores and bunkers as well as minor and special-category exports with unspecified destination are not included.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Introduction: Concepts of the Global South". gssc.uni-koeln.de. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2016-09-04. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2016-10-18., "Concepts of the Global South" (PDF). gssc.uni-koeln.de. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2024-03-10.

- ↑ Nora, Mareï; Michel, Savy (January 2021). "Global South countries: The dark side of city logistics. Dualisation vs Bipolarisation". Transport Policy. 100: 150–160. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.11.001. S2CID 228984747.

This article aims to appraise the unevenness of logistics development throughout the world, by comparing city logistics (notion that we define) between developing countries (or Global South countries) (where 'modern' and 'traditional' models often coexist) and developed countries (or Global North countries)

- ↑ Mitlin, Diana; Satterthwaite, David (2013). Urban Poverty in the Global South: Scale and Nature. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 9780415624664 – โดยทาง Google Books.

- ↑ Mimiko, Nahzeem Oluwafemi (2012). Globalization: The Politics of Global Economic Relations and International Business. Carolina Academic Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-61163-129-6.

- ↑ Therien, Jean-Philippe (August 1999). "Beyond the North-South divide: The two tales of world poverty". Third World Quarterly. 20 (4): 723–742. doi:10.1080/01436599913523.

- ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อHickel2016 - ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อHickel2020 - ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อHickel 2021 - ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อ:0a - ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อ:0b - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Acharya, Amitav (3 July 2016). "Studying the Bandung conference from a Global IR perspective". Australian Journal of International Affairs. 70 (4): 342–357. doi:10.1080/10357718.2016.1168359. S2CID 156589520.

- ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อ:4 - ↑ Collyer, Fran M. (March 2021). "Australia and the Global South: Knowledge and the Ambiguities of Place and Identity". Journal of Historical Sociology. 34 (1): 41–54. doi:10.1111/johs.12312. S2CID 233625470.

- ↑ Moosavi, Leon (15 February 2019). "A Friendly Critique of 'Asian Criminology' and 'Southern Criminology'". The British Journal of Criminology. 59 (2): 257–275. doi:10.1093/bjc/azy045.

แหล่งข้อมูลอื่น[แก้]

- Share The World's Resources: The Brandt Commission Report, a 1980 report by a commission led by Willy Brandt that popularized the terminology

- Brandt 21 Forum, a recreation of the original commission with an updated report (information on original commission at site)