ผู้ใช้:Drgarden/ห้องทดลอง3

ความดันโลหิตสูง (อังกฤษ: Hypertension) เป็นโรคเรื้อรังชนิดหนึ่งที่ผู้ป่วยมีความดันเลือดในหลอดเลือดแดงสูงกว่าปกติทำให้หัวใจต้องบีบตัวมากขึ้นเพื่อสูบฉีดเลือดให้ไหลเวียนไปตามหลอดเลือด ความดันเลือดประกอบด้วยสองค่า ได้แก่ ความดันในหลอดเลือดขณะที่หัวใจบีบตัว (ความดันช่วงหัวใจบีบ) และ ความดันในหลอดเลือดขณะที่หัวใจคลายตัว (ความดันช่วงหัวใจคลาย) ความดันเลือดปกติขณะพักอยู่ในช่วง 100-140 มิลลิเมตรปรอทในช่วงหัวใจบีบ และ 60-90 มิลลิเมตรปรอทในช่วงหัวใจคลาย ดังนั้นผู้ที่มีภาวะความดันโลหิตสูงจึงหมายถึงผู้ที่มีความดันเลือดเท่ากับหรือสูงกว่า 140/90 มิลลิเมตรปรอท

ความดันโลหิตสูง แบ่งออกได้เป็นความดันโลหิตสูงปฐมภูมิ (ไม่ทราบสาเหตุ) และความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิ ผู้ป่วยส่วนใหญ่ราวร้อยละ 90-95 จัดเป็นความดันโลหิตสูงปฐมภูมิ หมายถึงมีความดันโลหิตสูงโดยไม่มีสาเหตุชัดเจน[1] ที่เหลืออีกร้อยละ 5-10 เป็นความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิมักจะมีสาเหตุจากภาวะอื่นที่มีผลต่อไต หลอดเลือดแดง หัวใจ หรือระบบต่อมไร้ท่อ

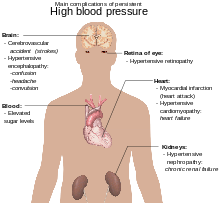

ความดันโลหิตสูงเป็นปัจจัยเสี่ยงสำคัญของโรคหลอดเลือดสมอง กล้ามเนื้อหัวใจตายเหตุขาดเลือด หัวใจวาย หลอดเลือดโป่งพอง (เช่นหลอดเลือดแดงใหญ่เอออร์ตาโป่งพอง) โรคของหลอดเลือดส่วนปลาย และเป็นสาเหตุของโรคไตเรื้อรัง ความดันโลหิตที่สูงในระดับปานกลางก็มีความสัมพันธ์กับอายุขัยที่สั้นลง การปรับเปลี่ยนวิถีชีวิตและพฤติกรรมการกินอาหารสามารถช่วยลดความดันเลือดและลดความเสี่ยงจากภาวะแทรกซ้อนต่างๆ ได้ แต่สำหรับผู้ป่วยที่รักษาด้วยการปรับเปลี่ยนวิถีชีวิตแล้วไม่ได้ผลหรือไม่เพียงพอจำเป็นต้องรักษาด้วยยา

การจำแนกประเภท[แก้]

ผู้ใหญ่[แก้]

| การจำแนกประเภทความดันเลือดโดย JNC7[2] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ประเภท | ความดันช่วงหัวใจบีบ (Systolic blood pressure; SBP) |

ความดันช่วงหัวใจคลาย (Diastolic blood pressure; DBP) | ||

| มม.ปรอท (mmHg) |

กิโลปาสกาล (kPa) |

มม.ปรอท (mmHg) |

กิโลปาสกาล (kPa) | |

| ปกติ | 90–119 | 12–15.9 | 60–79 | 8.0–10.5 |

| ก่อนความดันโลหิตสูง | 120–139 | 16.0–18.5 | 80–89 | 10.7–11.9 |

| ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 1 | 140–159 | 18.7–21.2 | 90–99 | 12.0–13.2 |

| ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 2 | ≥160 | ≥21.3 | ≥100 | ≥13.3 |

| ความดันโลหิตเฉพาะ ช่วงหัวใจบีบสูง |

≥140 | ≥18.7 | <90 | <12.0 |

| การจำแนกประเภทความดันเลือดโดย ESH-ESC[3] BHS IV[4] และสมาคมความดันโลหิตสูงแห่งประเทศไทย[5] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ประเภท | ความดันช่วงหัวใจบีบ (มม.ปรอท) |

ความดันช่วงหัวใจคลาย (มม.ปรอท) | |

| เหมาะสม | <120 | และ | <80 |

| ปกติ | 120–129 | และ/หรือ | 80–84 |

| ปกติค่อนสูง | 130–139 | และ/หรือ | 85–89 |

| ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 1 | 140–159 | และ/หรือ | 90-99 |

| ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 2 | 160-179 | และ/หรือ | 100-109 |

| ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 3 | ≥180 | และ/หรือ | ≥110 |

| ความดันโลหิตเฉพาะ ช่วงหัวใจบีบสูง |

≥140 | และ/หรือ | <90 |

ในผู้ใหญ่อายุตั้งแต่ 18 ปีขึ้นไป ความดันโลหิตสูงหมายถึงภาวะที่มีผลการวัดความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจบีบ และ/หรือความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจคลาย มากกว่าค่าความดันเลือดปกติอย่างต่อเนื่อง (ในปัจจุบันถือเอาค่าความดันเลือดปกติคือ ความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจบีบ 139 มิลลิเมตรปรอท และความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจคลาย 89 มิลลิเมตรปรอท: ดูตาราง — การจำแนกประเภทความดันเลือดโดย JNC7) หากวัดความดันโลหิตโดยใช้เครื่องมอนิเตอร์ติดตัว 24 ชั่วโมง (24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitor) หรือเครื่องวัดความดันโลหิตที่บ้าน (home blood pressure monitoring) ให้ถือเกณฑ์ความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจบีบที่ตั้งแต่ 135 มิลลิเมตรขึ้นไป หรือความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจคลายที่ตั้งแต่ 85 มิลลิเมตรปรอทขึ้นไป[6]

แนวทางการรักษาความดันโลหิตสูงในปัจจุบันจัดกลุ่มผู้ที่มีความดันเลือดสูงแต่ไม่ถึงเกณฑ์เป็นความดันโลหิตสูงเพื่อบอกถึงความเสี่ยงต่อเนื่องในผู้ที่ความดันโลหิตค่อนข้างสูงแต่ยังอยู่ในค่าปกติ โดย JNC7 (ค.ศ. 2003)[2] ใช้คำว่า "ก่อนความดันโลหิตสูง" (prehypertension) ในผู้ที่มีความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจบีบในช่วง 120-139 มิลลิเมตรปรอท และ/หรือความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจคลาย 80-89 มิลลิเมตรปรอท ในขณะที่ ESH-ESC Guidelines (ค.ศ. 2007)[3] BHS IV (ค.ศ. 2004)[4] รวมถึงแนวทางการรักษาโดยสมาคมความดันโลหิตสูงแห่งประเทศไทย (พ.ศ. 2555)[5] แบ่งประเภทผู้ที่ความดันเลือดต่ำกว่า 140/90 มิลลิเมตรปรอทตามค่าความดันมากน้อย โดยใช้จัดเป็นกลุ่ม "เหมาะสม" (optimal) "ปกติ" (normal) และ "ปกติค่อนสูง" (high normal) (ดูตาราง — การจำแนกประเภทความดันเลือดโดย ESH-ESC BHS IV และสมาคมความดันโลหิตสูงแห่งประเทศไทย)

ในช่วงความดันโลหิตสูงก็มีการจัดกลุ่มตามความรุนแรงเช่นเดียวกัน โดย JNC7 แยกกลุ่มที่มีความดันโลหิตสูงกว่า 140/90 มิลลิเมตรปรอทออกเป็น "ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 1" (hypertension stage I) "ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 2" (hypertension stage II) และ "ความดันโลหิตเฉพาะช่วงหัวใจบีบสูง" (isolated systolic hypertension) ความดันโลหิตเฉพาะช่วงหัวใจบีบสูงหมายถึงผู้ที่มีความดันโลหิตช่วงหัวใจบีบสูงแต่ความดันโลหิตช่วงหัวใจคลายปกติ มักพบในผู้สูงอายุ[2] ในขณะที่ ESH-ESC Guidelines (ค.ศ. 2007)[3] BHS IV (ค.ศ. 2004)[4] และแนวทางการรักษาของประเทศไทย (พ.ศ. 2555)[5] มีการเพิ่มกลุ่ม "ความดันโลหิตสูงระยะที่ 3" หมายถึงผู้ที่มีความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจบีบมากกว่า 179 มิลลิเมตรปรอท หรือความดันเลือดช่วงหัวใจคลายมากกว่า 109 มิลลิเมตรปรอท ความดันโลหิตสูง "ชนิดดื้อ" (resistant) หมายถึงการใช้ยาไม่สามารถลดความดันเลือดกลับมาอยู่ในระดับปกติได้[2]

ทารกและทารกแรกเกิด[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงในทารกพบได้น้อยมากคือประมาณร้อยละ 0.2-3 ของจำนวนทารกแรกเกิด และการวัดความดันโลหิตมักจะไม่ทำกันเป็นประจำในทารกแรกเกิดที่สุขภาพดี[7] ความดันโลหิตสูงพบได้บ่อยกว่าในทารกที่มีภาวะเสี่ยง การประเมินว่าความดันเลือดนั้นปกติหรือไม่ในของทารกแรกเกิดต้องคำนึงถึงปัจจัยต่างๆ อาทิ อายุครรภ์ อายุหลังการปฏิสนธิ และน้ำหนักแรกเกิด[7]

เด็กและวัยรุ่น[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงพบได้ค่อนข้างบ่อยในเด็กและวัยรุ่น (2-9% ขึ้นกับอายุ เพศ และเชื้อชาติ)[8] และสัมพันธ์กับปัจจัยเสี่ยงต่อความเจ็บป่วยในระยะยาว[9] ในปัจจุบันแนะนำให้ตรวจวัดความดันโลหิตในเด็กอายุเกิน 3 ปีขึ้นไปที่มาตรวจรักษาหรือตรวจสุขภาพ แต่หากพบความดันเลือดสูงจะต้องตรวจยืนยันซ้ำก่อนที่จะจำแนกว่าเด็กมีภาวะความดันโลหิตสูง[9]

ในเด็กความดันเลือดจะเพิ่มขึ้นตามอายุ ความดันโลหิตสูงในเด็กหมายถึงการมีค่าเฉลี่ยของความดันขณะหัวใจบีบหรือความดันขณะหัวใจคลายจากการวัดความดันเลือดตั้งแต่สามครั้งขึ้นไป มากกว่าหรือเท่ากับเปอร์เซ็นไทล์ที่ 95 ของความดันโลหิตในอายุ เพศ และความสูงเดียวกัน ส่วนภาวะก่อนความดันโลหิตสูงในเด็กหมายถึงค่าเฉลี่ยของความดันขณะหัวใจบีบหรือความดันขณะหัวใจคลายอยู่ระหว่างเปอร์เซ็นไทล์ที่ 90-95 ของความดันโลหิตในอายุ เพศ และความสูงเดียวกัน[9] ส่วนการวินิจฉัยและจัดจำแนกประเภทในวัยรุ่นให้ใช้เกณฑ์เหมือนกับผู้ใหญ่[9]

อาการและอาการแสดง[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงมักไม่ค่อยมาพร้อมกับอาการใดๆ จำเพาะ ส่วนใหญ่มักตรวจพบจากการตรวจคัดกรองหรือพบโดยบังเอิญจากการมาพบแพทย์ด้วยภาวะอื่นๆ ผู้ป่วยความดันโลหิตสูงจำนวนหนึ่งมักบอกอาการปวดศีรษะโดยเฉพาะบริเวณท้ายทอยในช่วงเช้า เวียนศีรษะ รู้สึกหมุน มีเสียงในหู หน้ามืดหรือเป็นลม[10]

ในการตรวจร่างกาย ผู้ป่วยที่สงสัยภาวะความดันโลหิตสูงจะตรวจพบโรคที่จอตาจากความดันโลหิตสูง (hypertensive retinopathy) จากการตรวจตาโดยใช้กล้องส่องตรวจในตา (ophthalmoscopy)[11] โรคที่จอตาจากความดันโลหิตสูงสามารถจำแนกออกได้เป็น 4 ระดับตามความรุนแรง การตรวจตาจะช่วยบอกว่าผู้ป่วยมีความดันโลหิตสูงมาเป็นระยะเวลานานเท่าไร[10]

ความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิ[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิ หมายถึงความดันโลหิตสูงที่สามารถระบุสาเหตุที่ทำให้เกิดได้ เช่น โรคไตหรือโรคต่อมไร้ท่อ ผู้ป่วยจะมีอาการและอาการแสดงบางอย่างที่บ่งบอกว่าเป็นความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิ เช่น สงสัยกลุ่มอาการคุชชิง (Cushing's syndrome) หากมีอาการอ้วนเฉพาะลำตัวแต่แขนขาลีบ (truncal obesity) การทนต่อกลูโคสบกพร่อง (glucose intolerance) หน้าบวมกลม (moon facies) ไขมันสะสมเป็นหนอกที่หลังและคอ ("buffalo hump") และริ้วลายสีม่วงที่ผิวหนัง (purple striae)[13] หรือผู้ที่ป่วยเป็นโรคไทรอยด์และสภาพโตเกินไม่สมส่วน (acromegaly) อาจทำให้เกิดความดันโลหิตสูงได้โดยจะตรวจพบอาการและอาการแสดงที่จำเพาะกับโรคนั้นๆ[13] เสียงบรุยต์ (bruit) ผิดปกติบริเวณท้องบ่งบอกภาวะหลอดเลือดแดงของไตตีบ (renal artery stenosis) ความดันโลหิตบริเวณแขนสูงแต่ความดันโลหิตที่ขาต่ำและ/หรือคลำชีพจรบริเวณหลอดเลือดแดงต้นขา (femoral artery) ได้เบาหรือไม่ได้เลยบ่งบอกภาวะหลอดเลือดเอออร์ตาแคบ (aortic coarctation) ภาวะที่มีความดันโลหิตสูงเป็นช่วงๆ ไม่สม่ำเสมอร่วมกับปวดศีรษะ ใจสั่น ซีด เหงื่อออกควรสงสัยโรคฟีโอโครโมไซโตมา (pheochromocytoma)[13]

ความดันโลหิตสูงวิกฤต[แก้]

ภาวะที่ความดันเลือดขึ้นสูงอย่างรุนแรง คือตั้งแต่ 180 มิลลิเมตรปรอทสำหรับความดันช่วงหัวใจบีบ หรือ 110 มิลลิเมตรปรอทสำหรับความดันช่วงหัวใจคลาย เรียกว่าภาวะความดันโลหิตสูงวิกฤต (hypertensive crisis) ซึ่งที่ระดับความดันเลือดดังกล่าวมีความเสี่ยงสูงที่จะเกิดภาวะแทรกซ้อนได้ ผู้ป่วยที่ความดันโลหิตสูงระดับนี้อาจไม่มีอาการ หรือมีรายงานว่าปวดศีรษะ (ราวร้อยละ 22) [14] และเวียนศีรษะมากกว่าประชากรทั่วไป[10] อาการอื่นๆ ที่เกิดร่วมกับภาวะความดันโลหิตสูงวิกฤต เช่น ตาพร่ามองภาพไม่ชัด หรือหายใจเหนื่อยหอบจากหัวใจล้มเหลว หรือรู้สึกไม่สบายดัวเนื่องจากไตวาย[13] ผู้ป่วยความดันโลหิตสูงวิกฤตส่วนใหญ่ทราบอยู่แล้วว่าเป็นโรคความดันโลหิตสูงแต่มีสิ่งกระตุ้นเข้ามาทำให้ความดันเลือดสูงขึ้นทันที[15] ความดันโลหิตสูงวิกฤตแบ่งออกได้เป็นสองประเภท คือ ความดันโลหิตสูงฉุกเฉิน (hypertensive emergency) และความดันโลหิตสูงเร่งด่วน (hypertensive urgency) ซึ่งต่างกันตรงที่มีอาการแสดงของอวัยวะถูกทำลายหรือไม่

ความดันโลหิตสูงฉุกเฉิน (hypertensive emergency) เป็นภาวะที่วินิจฉัยเมื่อมีความดันโลหิตสูงอย่างรุนแรงจนอวัยวะตั้งแต่ 1 อย่างขึ้นไปถูกทำลาย ตัวอย่างเช่น โรคสมองจากความดันโลหิตสูง (hypertensive encephalopathy) เกิดจากสมองบวมและเสียการทำงาน จะมีอาการปวดศีรษะและระดับความรู้สึกตัวเปลี่ยนแปลง เช่น ซึม สับสน อาการแสดงของอวัยวะเป้าหมายถูกทำลายที่ตา ได้แก่ จานประสาทตาบวม (papilloedema) และ/หรือมีเลือดออกและของเหลวซึมที่ก้นตา อาการเจ็บหน้าอกอาจแสดงถึงกล้ามเนื้อหัวใจเสียหายซึ่งอาจดำเนินต่อไปเป็นกล้ามเนื้อหัวใจตายหรือเกิดการฉีกเซาะของผนังหลอดเลือดแดงใหญ่เอออร์ตา อาการหายใจลำบาก ไอ เสมหะมีเลือดปนเป็นอาการแสดงของปอดบวมน้ำ (pulmonary edema) เนื่องจากหัวใจห้องล่างซ้ายล้มเหลว กล่าวคือหัวใจห้องล่างซ้ายไม่สามารถสูบฉีดเลือดจากปอดไปยังระบบหลอดเลือดแดงได้เพียงพอ[15] อาจเกิดไตเสียหายเฉียบพลัน และโลหิตจางจากเม็ดเลือดแดงแตกชนิดไมโครแองจีโอพาติก (การทำลายเม็ดเลือดแดงชนิดหนึ่ง)[15] เมื่อเกิดภาวะนี้จำเป็นต้องรีบลดความดันโลหิตเพื่อหยุดยั้งความเสียหายของอวัยวะเป้าหมาย[15]

ในทางตรงข้ามหากผู้ป่วยมีความดันโลหิตสูงกว่า 180/100 มิลลิเมตรปรอทแต่ไม่พบความเสียหายของอวัยวะเป้าหมายจะเรียกภาวะนี้ว่า ความดันโลหิตสูงเร่งด่วน (hypertensive urgency) ยังไม่มีหลักฐานยืนยันถึงความจำเป็นต้องรีบลดความดันโลหิตในผู้ป่วยกลุ่มนี้หากไม่มีการทำลายอวัยวะ และการลดความดันโลหิตอย่างรวดเร็วก็ไม่ได้ปราศจากความเสี่ยง[13] ในภาวะนี้สามารถค่อยๆ ลดความดันโลหิตลงด้วยยาลดความดันชนิดรับประทานให้กลับสู่ระดับปกติใน 24 ถึง 48 ชั่วโมง[15]

ในสตรีตั้งครรภ์[แก้]

สตรีตั้งครรภ์มีภาวะความดันโลหิตสูงเกิดขึ้นราวร้ยละ 8-10[13] หญิงที่มีความดันโลหิตสูงขณะตั้งครรภ์ส่วนใหญ่มักเป็นความดันโลหิตสูงปฐมภูมิอยู่ก่อนแล้ว ความดันโลหิตสูงในระหว่างตั้งครรภ์อาจเป็นอาการแสดงแรกของโรคพิษแห่งครรภ์ระยะก่อนชัก (pre-eclampsia) ซึ่งเป็นภาวะทางสูติศาสตร์ที่ร้ายแรงในช่วงครึ่งหลังของการตั้งครรภ์และระยะหลังคลอด[13] โรคพิษแห่งครรภ์ระยะก่อนชักเป็นภาวะที่มีความดันโลหิตสูงและมีโปรตีนในปัสสาวะ[13] พบราวร้อยละ 5 ของการตั้งครรภ์ และเป็นสาเหตุราวร้อยละ 16 ของการเสียชีวิตของมารดาทั่วโลก[13] โรคพิษแห่งครรภ์ระยะก่อนชักเพิ่มความเสี่ยงของการตายปริกำเนิดเป็นสองเท่า[13] โดยทั่วไปแล้วโรคนี้ไม่มีอาการและตรวจพบได้จากการฝากครรภ์เป็นประจำ อาการของโรคนี้ที่พบได้บ่อยคือปวดศีรษะ ตาพร่ามัว (มักเห็นแสงวูบวาบ) ปวดจุกแน่นลิ้นปี่ และบวม โรคพิษแห่งครรภ์ระยะก่อนชักบางครั้งจะดำเนินต่อไปเป็นโรคร้ายแรงถึงแก่ชีวิตเรียกว่าโรคพิษแห่งครรภ์ระยะชัก (eclampsia) ซึ่งมีภาวะความดันโลหิตสูงฉุกเฉินร่วมกับภาวะแทรกซ้อนรุนแรงหลายอย่างเช่นมองภาพไม่เห็น สมองบวม ชัก ไตวาย ปอดบวมน้ำ และมีภาวะเลือดแข็งตัวในหลอดเลือดแบบแพร่กระจาย (disseminated intravascular coagulation; ความผิดปกติของการแข็งตัวของเลือดอย่างหนึ่ง)[13][16]

ในทารกและเด็ก[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงในทารกแรกเกิดและทารกอาจมาด้วยเลี้ยงไม่โต ชัก งอแงร้องกวน ง่วงซึม และหายใจลำบาก[17] ความดันโลหิตสูงในเด็กอาจทำให้ปวดศีรษะ อ่อนล้า เลี้ยงไม่โต มองภาพไม่ชัด เลือดกำเดาออก และใบหน้าเป็นอัมพาต[7][17]

ภาวะแทรกซ้อน[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตเป็นปัจจัยเสี่ยงของการเสียชีวิตก่อนวัยอันควรที่สามารถป้องกันได้ที่สำคัญที่สุดทั่วโลก[18] ความดันโลหิตสูงเพิ่มความเสี่ยงของโรคหัวใจขาดเลือด[19] โรคหลอดเลือดสมอง[13] โรคของหลอดเลือดส่วนปลาย[20] และโรคของหัวใจและหลอดเลือดอื่นๆ รวมถึงหัวใจล้มเหลว หลอดเลือดแดงใหญ่เอออร์ตาโป่งพอง โรคหลอดเลือดแดงแข็งทั่วร่างกาย และหลอดเลือดปอดอุดตัน[13] ความดันโลหิตยังเป็นปัจจัยเสี่ยงต่อการรับรู้บกพร่องและภาวะสมองเสื่อม และไตวายเรื้อรัง[13] ภาวะแทรกซ้อนอื่นๆ ได้แก่ โรคที่จอตาจากความดันโลหิตสูง (hypertensive retinopathy) และโรคสมองจากความดันโลหิตสูง (hypertensive encephalopathy)[21]

สาเหตุ[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงแบบปฐมภูมิ[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงแบบปฐมภูมิ (primary hypertension) หรือความดันโลหิตสูงไม่ทราบสาเหตุ (essential hypertension) เป็นความดันโลหิตสูงชนิดที่พบได้บ่อยที่สุด ประมาณร้อยละ 90-95 ของผู้ป่วยความดันโลหิตสูงทั้งหมด[1] ในสภาพสังคมปัจจุบันพบว่าความดันเลือดเพิ่มขึ้นตามอายุ และความเสี่ยงของการเป็นความดันโลหิตสูงในวัยสูงอายุนั้นสูง[22] ความดันโลหิตสูงเป็นผลจากความสัมพันธ์ซับซ้อนระหว่างพันธุกรรมและสิ่งแวดล้อม มีการศึกษาพบยีนหลายชนิดที่มีผลเล็กน้อยต่อความดันโลหิต[23] และมียีนจำนวนน้อยมากที่มีผลอย่างมากต่อความดันโลหิต[24] แต่สุดท้ายปัจจัยด้านพันธุกรรมต่อความดันโลหิตสูงยังไม่เป็นที่เข้าใจกันมากนักในปัจจุบัน ปัจจัยทางสิ่งแวดล้อมหลายอย่างที่มีผลต่อความดันเลือด พฤติกรรมที่ช่วยลดความดันโลหิตอย่างชัดเจน อาทิ การลดการบริโภคเกลือ[25] การรับประทานผลไม้และอาหารที่มีไขมันต่ำ (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH diet)) การออกกำลังกาย[26] การลดน้ำหนัก[27] การลดการบริโภคแอลกอฮอล์[28] ปัจจัยที่อาจมีผลต่อความดันโลหิตสูงแต่ยังไม่ชัดเจน ได้แก่ ความเครียด[29] การบริโภคคาเฟอีน[30] และการขาดวิตามินดี[31] เชื่อกันว่าภาวะดื้อต่ออินซูลิน (insulin resistance) ซึ่งพบได้บ่อยในคนอ้วนและเป็นองค์ประกอบของกลุ่มอาการเมแทบอลิก (metabolic syndrome) เป็นสาเหตุของความดันโลหิตสูง[32] การศึกษาเร็วๆ นี้พบนัยว่าเหตุการณ์ที่เกิดขึ้นในช่วงต้นของชีวิต เช่น น้ำหนักแรกเกิดน้อย มารดาสูบบุหรี่ขณะตั้งครรภ์ และการไม่ได้เลี้ยงลูกด้วยนมแม่ อาจเป็นปัจจัยเสี่ยงของความดันโลหิตสูงไม่ทราบสาเหตุในผู้ใหญ่[33] แต่ทั้งนี้กลไกเชื่อมโยงระหว่างปัจจัยเสี่ยงดังกล่าวกับความดันโลหิตสูงยังคลุมเครือ[33]

ความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิ[แก้]

ความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิมีสาเหตุที่สามารถระบุได้ (ดูตาราง — สาเหตุของความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิ) โรคไตเป็นสาเหตุส่วนใหญ่ที่ทำให้เกิดความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิ[13] ความดันโลหิตสูงยังอาจเกิดจากโรคต่อมไร้ท่อต่างๆ เช่น กลุ่มอาการคุชชิง ภาวะต่อมไทรอยด์ทำงานมากเกิน ภาวะต่อมไทรอยด์ทำงานน้อย สภาพโตเกินไม่สมส่วน กลุ่มอาการคอนน์ (Conn's syndrome) หรือภาวะอัลโดสเตอโรนสูง ภาวะต่อมพาราไทรอยด์ทำงานมากเกิน และฟีโอโครโมไซโตมา[13][34] สาเหตุอื่นๆ ของความดันโลหิตสูงแบบทุติยภูมิเช่น โรคอ้วน อาการหยุดหายใจขณะหลับ การตั้งครรภ์ หลอดเลือดเอออร์ตาแคบ (coarctation of the aorta) ยาบางชนิดและสมุนไพร เช่นการบริโภคชะเอมเทศมากเกิน และยาเสพติดบางชนิด[13][35]

พยาธิสรีรวิทยา[แก้]

ในผู้ป่วยความดันโลหิตสูงไม่ทราบสาเหตุจะมีความต้านทานการไหลของเลือดในร่างกาย (หรือเรียกว่าแรงต้านส่วนปลายทั้งหมด; total peripheral resistance) สูงขึ้นทำให้ความดันเลือดสูงขึ้น ในขณะที่ปริมาตรเลือดส่งออกจากหัวใจต่อนาที (cardiac output) ยังปกติ[36] มีหลักฐานอธิบายสาเหตุว่าในผู้ที่อายุน้อยบางคนที่มีภาวะก่อนความดันโลหิตสูง (prehypertension) มีปริมาตรเลือดส่งออกจากหัวใจต่อนาทีสูง อัตราหัวใจเต้นสูงขึ้น และแรงต้านส่วนปลายทั้งหมดยังปกติ ซึ่งเรียกว่าภาวะ "hyperkinetic borderline hypertension"[37] เมื่อคนเหล่านี้อายุมากขึ้น ปริมาตรเลือดส่งออกจากหัวใจต่อนาทีจะลดลง และแรงต้านส่วนปลายทั้งหมดเพิ่มขึ้นตามอายุ ซึ่งเป็นลักษณะตรงตามแบบของความดันโลหิตสูงชนิดไม่ทราบสาเหตุดังที่กล่าวข้างต้น[37] แต่กลไกดังกล่าวยังเป็นที่ถกเถียงกันหากจะใช้อธิบายรูปแบบการเกิดความดันโลหิตสูงในผู้ป่วยทุกราย[38]

กลไกของแรงต้านหลอดเลือดส่วนปลายเพิ่มขึ้นที่ทำให้เกิดความดันโลหิตสูง ส่วนใหญ่เกิดจากการตีบแคบลงของหลอดเลือดแดงขนาดเล็กและหลอดเลือดแดงจิ๋ว (arteriole)[39] และอาจมีส่วนจากการลดจำนวนและความหนาแน่นของหลอดเลือดฝอยด้วย[40] ความดันโลหิตสูงยังทำให้ความยืดหยุ่นตาม (compliance) ของหลอดเลือดดำลดลง[41] ซึ่งทำให้เลือดไหลจากหลอดเลือดดำกลับหัวใจมากขึ้น จนเพิ่มการทำงานของหัวใจ (ชนิด preload) เป็นเหตุให้เกิดหัวใจวายช่วงหัวใจคลาย (diastolic dysfunction) ขึ้นในที่สุด แต่ถึงกระนั้นบทบาทของการบีบเส้นเลือดเพิ่มขึ้นมีผลทำให้เกิดความดันโลหิตสูงชนิดไม่ทราบสาเหตุหรือไม่ก็ยังไม่เป็นที่ชัดเจน[42]

ความดันชีพจร (pulse pressure; ผลต่างความดันช่วงหัวใจบีบและคลาย) มักเพิ่มขึ้นในผู้สูงอายุที่มีความดันโลหิตสูง หมายความว่าความดันช่วงหัวใจบีบสูงขึ้นอย่างผิดปกติแต่ความดันช่วงหัวใจคลายอาจปกติหรือต่ำ เรียกภาวะนี้ว่า ความดันโลหิตเฉพาะช่วงหัวใจบีบสูง (isolated systolic hypertension)[43] ผลจากความดันชีพจรที่เพิ่มขึ้นดังกล่าวอธิบายจากความแข็งของหลอดเลือดแดง (arterial stiffness) ที่มักสัมพันธ์กับความชราและอาจแย่ลงได้จากภาวะความดันโลหิตสูง[44]

มีกลไกหลายอย่างที่ถูกเสนอขึ้นเพื่ออธิบายการเพิ่มขึ้นของแรงต้านหลอดเลือดส่วนปลายในภาวะความดันโลหิตสูง ที่พบหลักฐานเกี่ยวข้องมากได้แก่

- การรบกวนการควบคุมเกลือและน้ำของไต โดยเฉพาะความผิดปกติของระบบเรนิน-แองจิโอเทนซินในไต[45] และ/หรือ

- ความผิดปกติของระบบประสาทซิมพาเทติก[46]

กลไกดังกล่าวเชื่อว่าน่าจะเกิดร่วมกัน และเป็นไปได้ที่ทั้งสองกลไกมีผลร่วมกันในผู้ป่วยความดันโลหิตสูงชนิดไม่ทราบสาเหตุส่วนใหญ่ มีการสันนิษฐานว่าการทำงานผิดปกติของเนื้อเยื่อบุโพรงหลอดเลือด (endothelial dysfunction) และการอักเสบของหลอดเลือดอาจมีผลต่อการเพิ่มขึ้นของแรงต้านหลอดเลือดส่วนปลายและความเสียหายของหลอดเลือดในภาวะความดันโลหิตสูง[47][48]

Diagnosis[แก้]

| System | Tests |

|---|---|

| Renal | Microscopic urinalysis, proteinuria, serum BUN (blood urea nitrogen) and/or creatinine |

| Endocrine | Serum sodium, potassium, calcium, TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone). |

| Metabolic | Fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides |

| Other | Hematocrit, electrocardiogram, and chest radiograph |

| Sources: Harrison's principles of internal medicine[12] others[49][50][51][52][53] | |

Hypertension is diagnosed on the basis of a persistently high blood pressure. Traditionally,[6] this requires three separate sphygmomanometer measurements at one monthly intervals.[54] Initial assessment of the hypertensive people should include a complete history and physical examination. With the availability of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitors and home blood pressure machines, the importance of not wrongly diagnosing those who have white coat hypertension has led to a change in protocols. In the United Kingdom, current best practice is to follow up a single raised clinic reading with ambulatory measurement, or less ideally with home blood pressure monitoring over the course of 7 days.[6] Pseudohypertension in the elderly or noncompressibility artery syndrome may also require consideration. This condition is believed to be due to calcification of the arteries resulting an abnormally high blood pressure readings with a blood pressure cuff while intra arterial measurements of blood pressure are normal.[55]

Once the diagnosis of hypertension has been made, physicians will attempt to identify the underlying cause based on risk factors and other symptoms, if present. Secondary hypertension is more common in preadolescent children, with most cases caused by renal disease. Primary or essential hypertension is more common in adolescents and has multiple risk factors, including obesity and a family history of hypertension.[56] Laboratory tests can also be performed to identify possible causes of secondary hypertension, and to determine whether hypertension has caused damage to the heart, eyes, and kidneys. Additional tests for diabetes and high cholesterol levels are usually performed because these conditions are additional risk factors for the development of heart disease and may require treatment.[1]

Serum creatinine is measured to assess for the presence of kidney disease, which can be either the cause or the result of hypertension. Serum creatinine alone may overestimate glomerular filtration rate and recent guidelines advocate the use of predictive equations such as the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula to estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).[2] eGFR can also provides a baseline measurement of kidney function that can be used to monitor for side effects of certain antihypertensive drugs on kidney function. Additionally, testing of urine samples for protein is used as a secondary indicator of kidney disease. Electrocardiogram (EKG/ECG) testing is done to check for evidence that the heart is under strain from high blood pressure. It may also show whether there is thickening of the heart muscle (left ventricular hypertrophy) or whether the heart has experienced a prior minor disturbance such as a silent heart attack. A chest X-ray or an echocardiogram may also be performed to look for signs of heart enlargement or damage to the heart.[13]

Prevention[แก้]

Much of the disease burden of high blood pressure is experienced by people who are not labelled as hypertensive.[57] Consequently, population strategies are required to reduce the consequences of high blood pressure and reduce the need for antihypertensive drug therapy. Lifestyle changes are recommended to lower blood pressure, before starting drug therapy. The 2004 British Hypertension Society guidelines[57] proposed the following lifestyle changes consistent with those outlined by the US National High BP Education Program in 2002[58] for the primary prevention of hypertension:

- maintain normal body weight for adults (e.g. body mass index 20–25 kg/m2)

- reduce dietary sodium intake to <100 mmol/ day (<6 g of sodium chloride or <2.4 g of sodium per day)

- engage in regular aerobic physical activity such as brisk walking (≥30 min per day, most days of the week)

- limit alcohol consumption to no more than 3 units/day in men and no more than 2 units/day in women

- consume a diet rich in fruit and vegetables (e.g. at least five portions per day);

Effective lifestyle modification may lower blood pressure as much an individual antihypertensive drug. Combinations of two or more lifestyle modifications can achieve even better results.[57]

Management[แก้]

Lifestyle modifications[แก้]

The first line of treatment for hypertension is identical to the recommended preventative lifestyle changes[59] and includes: dietary changes[60] physical exercise, and weight loss. These have all been shown to significantly reduce blood pressure in people with hypertension.[61] If hypertension is high enough to justify immediate use of medications, lifestyle changes are still recommended in conjunction with medication. Different programs aimed to reduce psychological stress such as biofeedback, relaxation or meditation are advertised to reduce hypertension. However, in general claims of efficacy are not supported by scientific studies, which have been in general of low quality.[62][63][64]

Dietary change such as a low sodium diet is beneficial. A long term (more than 4 weeks) low sodium diet in Caucasians is effective in reducing blood pressure, both in people with hypertension and in people with normal blood pressure.[65] Also, the DASH diet, a diet rich in nuts, whole grains, fish, poultry, fruits and vegetables promoted in the USA by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute lowers blood pressure. A major feature of the plan is limiting intake of sodium, although the diet is also rich in potassium, magnesium, calcium, as well as protein.[66]

Medications[แก้]

Several classes of medications, collectively referred to as antihypertensive drugs, are currently available for treating hypertension. Prescription should take into account the person's cardiovascular risk (including risk of myocardial infarction and stroke) as well as blood pressure readings, in order to gain a more accurate picture of the person's cardiovascular profile.[67] If drug treatment is initiated the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Seventh Joint National Committee on High Blood Pressure (JNC-7)[2] recommends that the physician not only monitor for response to treatment but should also assess for any adverse reactions resulting from the medication. Reduction of the blood pressure by 5 mmHg can decrease the risk of stroke by 34%, of ischaemic heart disease by 21%, and reduce the likelihood of dementia, heart failure, and mortality from cardiovascular disease.[68] The aim of treatment should be to reduce blood pressure to <140/90 mmHg for most individuals, and lower for those with diabetes or kidney disease (some medical professionals recommend keeping levels below 120/80 mmHg).[67][69] If the blood pressure goal is not met, a change in treatment should be made as therapeutic inertia is a clear impediment to blood pressure control.[70]

Guidelines on the choice of agents and how to best to step up treatment for various subgroups have changed over time and differ between countries. The best first line agent is disputed.[71] The Cochrane collaboration, World Health Organization and the United States guidelines supports low dose thiazide-based diuretic as first line treatment.[71][72] The UK guidelines emphasise calcium channel blockers (CCB) in preference for people over the age of 55 years or if of African or Caribbean family origin, with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) used first line for younger people.[73] In Japan starting with any one of six classes of medications including: CCB, ACEI/ARB, thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, and alpha-blockers is deemed reasonable while in Canada all of these but alpha-blockers are recommended as options.[71]

Drug combinations[แก้]

The majority of people require more than one drug to control their hypertension. JNC7[2] and ESH-ESC guidelines[3] advocate starting treatment with two drugs when blood pressure is >20 mmHg above systolic or >10 mmHg above diastolic targets. Preferred combinations are renin–angiotensin system inhibitors and calcium channel blockers, or renin–angiotensin system inhibitors and diuretics.[74] Acceptable combinations include calcium channel blockers and diuretics, beta-blockers and diuretics, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and beta-blockers, or dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers with either verapamil or diltiazem. Unacceptable combinations are non-dihydropyridine calcium blockers (such as verapamil or diltiazem) and beta-blockers, dual renin–angiotensin system blockade (e.g. angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor + angiotensin receptor blocker), renin–angiotensin system blockers and beta-blockers, beta-blockers and anti-adrenergic drugs.[74] Combinations of an ACE-inhibitor or angiotensin II–receptor antagonist, a diuretic and an NSAID (including selective COX-2 inhibitors and non-prescribed drugs such as ibuprofen) should be avoided whenever possible due to a high documented risk of acute renal failure. The combination is known colloquially as a "triple whammy" in the Australian health industry.[59] Tablets containing fixed combinations of two classes of drugs are available and while convenient for the people, may be best reserved for those who have been established on the individual components.[75]

In the elderly[แก้]

Treating moderate to severe hypertension decreases death rates and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in people aged 60 and older.[76] There are limited studies of people over 80 years old but a recent review concluded that antihypertensive treatment reduced cardiovascular deaths and disease, but did not significantly reduce total death rates.[76] The recommended BP goal is advised as <140/90 mm Hg with thiazide diuretics being the first line medication in America,[77] and in the revised UK guidelines calcium-channel blockers are advocated as first line with targets of clinic readings <150/90, or <145/85 on ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring.[73]

Resistant hypertension[แก้]

Resistant hypertension is defined as hypertension that remains above goal blood pressure in spite of concurrent use of three antihypertensive agents belonging to different antihypertensive drug classes. Guidelines for treating resistant hypertension have been published in the UK[78] and US.[79]

Epidemiology[แก้]

As of 2000, nearly one billion people or ~26% of the adult population of the world had hypertension.[80] It was common in both developed (333 million) and undeveloped (639 million) countries.[80] However rates vary markedly in different regions with rates as low as 3.4% (men) and 6.8% (women) in rural India and as high as 68.9% (men) and 72.5% (women) in Poland.[81]

In 1995 it was estimated that 43 million people in the United States had hypertension or were taking antihypertensive medication, almost 24% of the adult United States population.[82] The prevalence of hypertension in the United States is increasing and reached 29% in 2004.[83][84] As of 2006 hypertension affects 76 million US adults (34% of the population) and African American adults have among the highest rates of hypertension in the world at 44%.[85] It is more common in blacks and native Americans and less in whites and Mexican Americans, rates increase with age, and is greater in the southeastern United States. Hypertension is more prevalent in men (though menopause tends to decrease this difference) and in those of low socioeconomic status.[1]

In children[แก้]

The prevalence of high blood pressure in the young is increasing.[86] Most childhood hypertension, particularly in preadolescents, is secondary to an underlying disorder. Aside from obesity, kidney disease is the most common (60–70%) cause of hypertension in children. Adolescents usually have primary or essential hypertension, which accounts for 85–95% of cases.[87]

History[แก้]

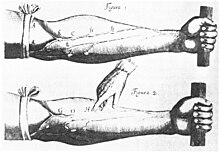

Modern understanding of the cardiovascular system began with the work of physician William Harvey (1578–1657), who described the circulation of blood in his book "De motu cordis". The English clergyman Stephen Hales made the first published measurement of blood pressure in 1733.[88][89] Descriptions of hypertension as a disease came among others from Thomas Young in 1808 and especially Richard Bright in 1836.[88] The first report of elevated blood pressure in a person without evidence of kidney disease was made by Frederick Akbar Mahomed (1849–1884).[90] However hypertension as a clinical entity came into being in 1896 with the invention of the cuff-based sphygmomanometer by Scipione Riva-Rocci in 1896.[91] This allowed the measurement of blood pressure in the clinic. In 1905, Nikolai Korotkoff improved the technique by describing the Korotkoff sounds that are heard when the artery is ausculated with a stethoscope while the sphygmomanometer cuff is deflated.[89]

Historically the treatment for what was called the "hard pulse disease" consisted in reducing the quantity of blood by blood letting or the application of leeches.[88] This was advocated by The Yellow Emperor of China, Cornelius Celsus, Galen, and Hippocrates.[88] In the 19th and 20th centuries, before effective pharmacological treatment for hypertension became possible, three treatment modalities were used, all with numerous side-effects: strict sodium restriction (for example the rice diet[88]), sympathectomy (surgical ablation of parts of the sympathetic nervous system), and pyrogen therapy (injection of substances that caused a fever, indirectly reducing blood pressure).[88][92] The first chemical for hypertension, sodium thiocyanate, was used in 1900 but had many side effects and was unpopular.[88] Several other agents were developed after the Second World War, the most popular and reasonably effective of which were tetramethylammonium chloride and its derivative hexamethonium, hydralazine and reserpine (derived from the medicinal plant Rauwolfia serpentina). A major breakthrough was achieved with the discovery of the first well-tolerated orally available agents. The first was chlorothiazide, the first thiazide diuretic and developed from the antibiotic sulfanilamide, which became available in 1958.[88][93]

Society and culture[แก้]

Awareness[แก้]

The World Health Organization has identified hypertension, or high blood pressure, as the leading cause of cardiovascular mortality. The World Hypertension League (WHL), an umbrella organization of 85 national hypertension societies and leagues, recognized that more than 50% of the hypertensive population worldwide are unaware of their condition.[94] To address this problem, the WHL initiated a global awareness campaign on hypertension in 2005 and dedicated May 17 of each year as World Hypertension Day (WHD). Over the past three years, more national societies have been engaging in WHD and have been innovative in their activities to get the message to the public. In 2007, there was record participation from 47 member countries of the WHL. During the week of WHD, all these countries – in partnership with their local governments, professional societies, nongovernmental organizations and private industries – promoted hypertension awareness among the public through several media and public rallies. Using mass media such as Internet and television, the message reached more than 250 million people. As the momentum picks up year after year, the WHL is confident that almost all the estimated 1.5 billion people affected by elevated blood pressure can be reached.[95]

Economics[แก้]

High blood pressure is the most common chronic medical problem prompting visits to primary health care providers in USA. The American Heart Association estimated the direct and indirect costs of high blood pressure in 2010 as $76.6 billion.[85] In the US 80% of people with hypertension are aware of their condition, 71% take some antihypertensive medication, but only 48% of people aware that they have hypertension are adequately controlled.[85] Adequate management of hypertension can be hampered by inadequacies in the diagnosis, treatment, and/or control of high blood pressure.[96] Health care providers face many obstacles to achieving blood pressure control, including resistance to taking multiple medications to reach blood pressure goals. People also face the challenges of adhering to medicine schedules and making lifestyle changes. Nonetheless, the achievement of blood pressure goals is possible, and most importantly, lowering blood pressure significantly reduces the risk of death due to heart disease and stroke, the development of other debilitating conditions, and the cost associated with advanced medical care.[97][98]

References[แก้]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Carretero OA, Oparil S (January 2000). "Essential hypertension. Part I: definition and etiology". Circulation. 101 (3): 329–35. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.101.3.329. PMID 10645931.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Chobanian AV; Bakris GL; Black HR; และคณะ (December 2003). "Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure". Hypertension. 42 (6): 1206–52. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. PMID 14656957.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Mancia G; De Backer G; Dominiczak A; และคณะ (September 2007). "2007 ESH-ESC Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: ESH-ESC Task Force on the Management of Arterial Hypertension". J. Hypertens. 25 (9): 1751–62. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f0580f. PMID 17762635.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Williams B; Poulter NR; Brown MJ; และคณะ (March 2004). "Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IV". J Hum Hypertens. 18 (3): 139–85. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001683. PMID 14973512.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 สมาคมความดันโลหิตสูงแห่งประเทศไทย (2012). แนวทางการรักษาโรคความดันโลหิตสูงในเวชปฏิบัติทั่วไป พ.ศ. 2555 (PDF). การประชุมวิชาการประจำปี ครั้งที่ 10 "Trends in Hypertension 2012" 17 กุมภาพันธ์ 2555. กรุงเทพฯ, ประเทศไทย. ISBN 1-111-22222-9. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 มิถุนายน พ.ศ. 2555.

{{cite conference}}: ตรวจสอบค่า|isbn=: checksum (help); ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 National Clinical Guidance Centre (August 2011). "7 Diagnosis of Hypertension, 7.5 Link from evidence to recommendations". Hypertension (NICE CG 127) (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 102. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2011-12-22. อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่สมเหตุสมผล มีนิยามชื่อ "NICE127 full" หลายครั้งด้วยเนื้อหาต่างกัน - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Dionne JM, Abitbol CL, Flynn JT (January 2012). "Hypertension in infancy: diagnosis, management and outcome". Pediatr. Nephrol. 27 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1007/s00467-010-1755-z. PMID 21258818.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Din-Dzietham R, Liu Y, Bielo MV, Shamsa F (September 2007). "High blood pressure trends in children and adolescents in national surveys, 1963 to 2002". Circulation. 116 (13): 1488–96. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683243. PMID 17846287.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (August 2004). "The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents". Pediatrics. 114 (2 Suppl 4th Report): 555–76. doi:10.1542/peds.114.2.S2.555. PMID 15286277.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Fisher ND, Williams GH (2005). "Hypertensive vascular disease". ใน Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS; และคณะ (บ.ก.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1463–81. ISBN 0-07-139140-1.

{{cite book}}: ใช้ et al. อย่างชัดเจน ใน|editor=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Wong T, Mitchell P (February 2007). Lancet. 369 (9559): 425–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60198-6. PMID 17276782.

{{cite journal}}:|title=ไม่มีหรือว่างเปล่า (help) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 Loscalzo, Joseph; Fauci, Anthony S.; Braunwald, Eugene; Dennis L. Kasper; Hauser, Stephen L; Longo, Dan L. (2008). Harrison's principles of internal medicine. McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 0-07-147691-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 O'Brien, Eoin; Beevers, D. G.; Lip, Gregory Y. H. (2007). ABC of hypertension. London: BMJ Books. ISBN 1-4051-3061-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Papadopoulos DP, Mourouzis I, Thomopoulos C, Makris T, Papademetriou V (December 2010). "Hypertension crisis". Blood Press. 19 (6): 328–36. doi:10.3109/08037051.2010.488052. PMID 20504242.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Marik PE, Varon J (June 2007). "Hypertensive crises: challenges and management". Chest. 131 (6): 1949–62. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2490. PMID 17565029.

- ↑ Gibson, Paul (July 30, 2009). "Hypertension and Pregnancy". eMedicine Obstetrics and Gynecology. Medscape. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-06-16.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Rodriguez-Cruz, Edwin (April 6, 2010). "Hypertension". eMedicine Pediatrics: Cardiac Disease and Critical Care Medicine. Medscape. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-06-16.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ "Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. สืบค้นเมื่อ 10 February 2012.

- ↑ Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (December 2002). "Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies". Lancet. 360 (9349): 1903–13. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8. PMID 12493255.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Singer DR, Kite A (June 2008). "Management of hypertension in peripheral arterial disease: does the choice of drugs matter?". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 35 (6): 701–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.01.007. PMID 18375152.

- ↑ Zeng C, Villar VA, Yu P, Zhou L, Jose PA (April 2009). "Reactive oxygen species and dopamine receptor function in essential hypertension". Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 31 (2): 156–78. doi:10.1080/10641960802621283. PMID 19330604.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Vasan, RS (2002-02-27). "Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 287 (8): 1003–10. doi:10.1001/jama.287.8.1003. PMID 11866648.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ Ehret GB; Munroe PB; Rice KM; และคณะ (October 2011). "Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk". Nature. 478 (7367): 103–9. doi:10.1038/nature10405. PMC 3340926. PMID 21909115.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Lifton, RP (2001-02-23). "Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension". Cell. 104 (4): 545–56. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00241-0. PMID 11239411.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ He, FJ (2009 Jun). "A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes". Journal of Human Hypertension. 23 (6): 363–84. doi:10.1038/jhh.2008.144. PMID 19110538.

{{cite journal}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|date=(help); ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ Dickinson HO; Mason JM; Nicolson DJ; และคณะ (February 2006). "Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". J. Hypertens. 24 (2): 215–33. doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000199800.72563.26. PMID 16508562.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Haslam DW, James WP (2005). "Obesity". Lancet. 366 (9492): 1197–209. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. PMID 16198769.

- ↑ Whelton PK; He J; Appel LJ; Cutler JA; Havas S; Kotchen TA; และคณะ (2002). "Primary prevention of hypertension:Clinical and public health advisory from The National High Blood Pressure Education Program". JAMA. 288 (15): 1882–8. doi:10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. PMID 12377087.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Cook JV, Williams B, Ford GA.Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials.J Hypertens. 2006;24:215-33.

- ↑ Mesas AE, Leon-Muñoz LM, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Lopez-Garcia E. The effect of coffee on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in hypertensive individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1113–26.

- ↑ Vaidya A, Forman JP (November 2010). "Vitamin D and hypertension: current evidence and future directions". Hypertension. 56 (5): 774–9. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140160. PMID 20937970.

- ↑ Sorof J, Daniels S (October 2002). "Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions". Hypertension. 40 (4): 441–447. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000032940.33466.12. PMID 12364344. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-06-03.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Lawlor, DA (2005 May). "Early life determinants of adult blood pressure". Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 14 (3): 259–64. doi:10.1097/01.mnh.0000165893.13620.2b. PMID 15821420.

{{cite journal}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|date=(help); ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ Dluhy RG, Williams GH. Endocrine hypertension. In: Wilson JD, Foster DW, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1998:729-49.

- ↑ Grossman E, Messerli FH (January 2012). "Drug-induced Hypertension: An Unappreciated Cause of Secondary Hypertension". Am. J. Med. 125 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.05.024. PMID 22195528.

- ↑ Conway J (April 1984). "Hemodynamic aspects of essential hypertension in humans". Physiol. Rev. 64 (2): 617–60. PMID 6369352.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Palatini P, Julius S (June 2009). "The role of cardiac autonomic function in hypertension and cardiovascular disease". Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 11 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1007/s11906-009-0035-4. PMID 19442329.

- ↑ Andersson OK, Lingman M, Himmelmann A, Sivertsson R, Widgren BR (2004). "Prediction of future hypertension by casual blood pressure or invasive hemodynamics? A 30-year follow-up study". Blood Press. 13 (6): 350–4. doi:10.1080/08037050410004819. PMID 15771219.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Folkow B (April 1982). "Physiological aspects of primary hypertension". Physiol. Rev. 62 (2): 347–504. PMID 6461865.

- ↑ Struijker Boudier HA, le Noble JL, Messing MW, Huijberts MS, le Noble FA, van Essen H (December 1992). "The microcirculation and hypertension". J Hypertens Suppl. 10 (7): S147–56. PMID 1291649.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Safar ME, London GM (August 1987). "Arterial and venous compliance in sustained essential hypertension". Hypertension. 10 (2): 133–9. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.10.2.133. PMID 3301662.

- ↑ Schiffrin EL (February 1992). "Reactivity of small blood vessels in hypertension: relation with structural changes. State of the art lecture". Hypertension. 19 (2 Suppl): II1–9. PMID 1735561.

- ↑ Chobanian AV (August 2007). "Clinical practice. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (8): 789–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp071137. PMID 17715411.

- ↑ Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA (May 2005). "Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 (5): 932–43. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000160548.78317.29. PMID 15731494.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Navar LG (December 2010). "Counterpoint: Activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system is the dominant contributor to systemic hypertension". J. Appl. Physiol. 109 (6): 1998–2000, discussion 2015. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00182.2010a. PMC 3006411. PMID 21148349.

- ↑ Esler M, Lambert E, Schlaich M (December 2010). "Point: Chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system is the dominant contributor to systemic hypertension". J. Appl. Physiol. 109 (6): 1996–8, discussion 2016. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00182.2010. PMID 20185633.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Versari D, Daghini E, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S (June 2009). "Endothelium-dependent contractions and endothelial dysfunction in human hypertension". Br. J. Pharmacol. 157 (4): 527–36. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00240.x. PMC 2707964. PMID 19630832.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL (July 2008). "Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 29 (7): 367–74. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. PMID 18579222.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Padwal RS; Hemmelgarn BR; Khan NA; และคณะ (May 2009). "The 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 25 (5): 279–86. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70491-X. PMC 2707176. PMID 19417858.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Padwal RJ; Hemmelgarn BR; Khan NA; และคณะ (June 2008). "The 2008 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 24 (6): 455–63. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70619-6. PMC 2643189. PMID 18548142.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Padwal RS; Hemmelgarn BR; McAlister FA; และคณะ (May 2007). "The 2007 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 23 (7): 529–38. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(07)70797-3. PMC 2650756. PMID 17534459.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Hemmelgarn BR; McAlister FA; Grover S; และคณะ (May 2006). "The 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part I – Blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 22 (7): 573–81. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(06)70279-3. PMC 2560864. PMID 16755312.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Hemmelgarn BR; McAllister FA; Myers MG; และคณะ (June 2005). "The 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part 1- blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 21 (8): 645–56. PMID 16003448.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ North of England Hypertension Guideline Development Group (1 August 2004). "Frequency of measurements". Essential hypertension (NICE CG18). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. p. 53. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2011-12-22.

- ↑ Franklin, SS (2012 Feb). "Unusual hypertensive phenotypes: what is their significance?". Hypertension. 59 (2): 173–8. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182956. PMID 22184330.

{{cite journal}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|date=(help); ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ Luma GB, Spiotta RT (2006). "Hypertension in children and adolescents". Am Fam Physician. 73 (9): 1558–68. PMID 16719248.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|month=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Williams, B (2004 Mar). "Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the fourth working party of the British Hypertension Society, 2004-BHS IV". Journal of Human Hypertension. 18 (3): 139–85. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1001683. PMID 14973512.

{{cite journal}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|date=(help); ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ Whelton PK; และคณะ (2002). "Primary prevention of hypertension. Clinical and public health advisory from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program". JAMA. 288 (15): 1882–1888. doi:10.1001/jama.288.15.1882. PMID 12377087.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ 59.0 59.1 "NPS Prescribing Practice Review 52: Treating hypertension". NPS Medicines Wise. September 1, 2010. สืบค้นเมื่อ November 5, 2010.

- ↑ Siebenhofer, A (2011-09-07). Siebenhofer, Andrea (บ.ก.). "Long-term effects of weight-reducing diets in hypertensive patients". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 9 (9): CD008274. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008274.pub2. PMID 21901719.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ Blumenthal JA; Babyak MA; Hinderliter A; และคณะ (January 2010). "Effects of the DASH diet alone and in combination with exercise and weight loss on blood pressure and cardiovascular biomarkers in men and women with high blood pressure: the ENCORE study". Arch. Intern. Med. 170 (2): 126–35. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.470. PMID 20101007.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Greenhalgh J, Dickson R, Dundar Y (October 2009). "The effects of biofeedback for the treatment of essential hypertension: a systematic review". Health Technol Assess. 13 (46): 1–104. doi:10.3310/hta13460 (inactive 2010-08-21). PMID 19822104.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of สิงหาคม 2010 (ลิงก์) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Rainforth MV, Schneider RH, Nidich SI, Gaylord-King C, Salerno JW, Anderson JW (December 2007). "Stress Reduction Programs in Patients with Elevated Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 9 (6): 520–8. doi:10.1007/s11906-007-0094-3. PMC 2268875. PMID 18350109.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Ospina MB; Bond K; Karkhaneh M; และคณะ (June 2007). "Meditation practices for health: state of the research". Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (155): 1–263. PMID 17764203.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ He, FJ (2004). MacGregor, Graham A (บ.ก.). "Effect of longer-term modest salt reduction on blood pressure". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD004937. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004937. PMID 15266549.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ "Your Guide To Lowering Your Blood Pressure With DASH" (PDF). สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-06-08.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Nelson, Mark. "Drug treatment of elevated blood pressure". Australian Prescriber (33): 108–112. สืบค้นเมื่อ August 11, 2010.

- ↑ Law M, Wald N, Morris J (2003). "Lowering blood pressure to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke: a new preventive strategy" (PDF). Health Technol Assess. 7 (31): 1–94. PMID 14604498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Shaw, Gina (2009-03-07). "Prehypertension: Early-stage High Blood Pressure". WebMD. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-07-03.

- ↑ Eni C. Okonofua; Kit N. Simpson; Ammar Jesri; Shakaib U. Rehman; Valerie L. Durkalski; Brent M. Egan (January 23, 2006). "Therapeutic Inertia Is an Impediment to Achieving the Healthy People 2010 Blood Pressure Control Goals". Hypertension. 47 (2006, 47:345): 345–51. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000200702.76436.4b. PMID 16432045. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-11-22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Klarenbach, SW (2010 May). "Identification of factors driving differences in cost effectiveness of first-line pharmacological therapy for uncomplicated hypertension". The Canadian journal of cardiology. 26 (5): e158–63. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(10)70383-4. PMC 2886561. PMID 20485695.

{{cite journal}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|date=(help); ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|coauthors=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|author=) (help) - ↑ Wright JM, Musini VM (2009). Wright, James M (บ.ก.). "First-line drugs for hypertension". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001841. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub2. PMID 19588327.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 National Institute Clinical Excellence (August 2011). "1.5 Initiating and monitoring antihypertensive drug treatment, including blood pressure targets". GC127 Hypertension: Clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2011-12-23.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Sever PS, Messerli FH (October 2011). "Hypertension management 2011: optimal combination therapy". Eur. Heart J. 32 (20): 2499–506. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr177. PMID 21697169.

- ↑ "2.5.5.1 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors". British National Formulary. Vol. No. 62. September 2011. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2011-12-22.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Musini VM, Tejani AM, Bassett K, Wright JM (2009). Musini, Vijaya M (บ.ก.). "Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD000028. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000028.pub2. PMID 19821263.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Aronow WS; Fleg JL; Pepine CJ; และคณะ (May 2011). "ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57 (20): 2037–114. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.008. PMID 21524875.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ "CG34 Hypertension - quick reference guide" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 28 June 2006. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-03-04.

- ↑ Calhoun DA; Jones D; Textor S; และคณะ (June 2008). "Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research". Hypertension. 51 (6): 1403–19. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141. PMID 18391085.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ 80.0 80.1 Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J (2005). "Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data". Lancet. 365 (9455): 217–23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. PMID 15652604.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, He J (January 2004). "Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review". J. Hypertens. 22 (1): 11–9. doi:10.1097/00004872-200401000-00003. PMID 15106785.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Burt VL; Whelton P; Roccella EJ; และคณะ (March 1995). "Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991". Hypertension. 25 (3): 305–13. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.25.3.305. PMID 7875754. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-06-05.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ 83.0 83.1 Burt VL; Cutler JA; Higgins M; และคณะ (July 1995). "Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the health examination surveys, 1960 to 1991". Hypertension. 26 (1): 60–9. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.26.1.60. PMID 7607734. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-06-05.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Ostchega Y, Dillon CF, Hughes JP, Carroll M, Yoon S (July 2007). "Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988 to 2004". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 55 (7): 1056–65. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01215.x. PMID 17608879.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 Lloyd-Jones D; Adams RJ; Brown TM; และคณะ (February 2010). "Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 121 (7): e46–e215. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. PMID 20019324.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|author-separator=ถูกละเว้น (help) - ↑ Falkner B (May 2009). "Hypertension in children and adolescents: epidemiology and natural history". Pediatr. Nephrol. 25 (7): 1219–24. doi:10.1007/s00467-009-1200-3. PMC 2874036. PMID 19421783.

- ↑ Luma GB, Spiotta RT (May 2006). "Hypertension in children and adolescents". Am Fam Physician. 73 (9): 1558–68. PMID 16719248.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 88.3 88.4 88.5 88.6 88.7 Esunge PM (October 1991). "From blood pressure to hypertension: the history of research". J R Soc Med. 84 (10): 621. PMC 1295564. PMID 1744849.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Kotchen TA (October 2011). "Historical trends and milestones in hypertension research: a model of the process of translational research". Hypertension. 58 (4): 522–38. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.177766. PMID 21859967.

- ↑ Swales JD, บ.ก. (1995). Manual of hypertension. Oxford: Blackwell Science. pp. xiii. ISBN 0-86542-861-1.

- ↑ Postel-Vinay N, บ.ก. (1996). A century of arterial hypertension 1896–1996. Chichester: Wiley. p. 213. ISBN 0-471-96788-2.

- ↑ Dustan HP, Roccella EJ, Garrison HH (September 1996). "Controlling hypertension. A research success story". Arch. Intern. Med. 156 (17): 1926–35. doi:10.1001/archinte.156.17.1926. PMID 8823146.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (ลิงก์) - ↑ Novello FC, Sprague JM (1957). "Benzothiadiazine dioxides as novel diuretics". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79 (8): 2028. doi:10.1021/ja01565a079.

- ↑ Chockalingam A (May 2007). "Impact of World Hypertension Day". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 23 (7): 517–9. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(07)70795-X. PMC 2650754. PMID 17534457.

- ↑ Chockalingam A (June 2008). "World Hypertension Day and global awareness". Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 24 (6): 441–4. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70617-2. PMC 2643187. PMID 18548140.

- ↑ Alcocer L, Cueto L (June 2008). "Hypertension, a health economics perspective". Therapeutic Advances in Cardiovascular Disease. 2 (3): 147–55. doi:10.1177/1753944708090572. PMID 19124418. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-06-20.

- ↑ William J. Elliott (October 2003). "The Economic Impact of Hypertension". The Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 5 (4): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2003.02463.x. PMID 12826765.

- ↑ Coca A (2008). "Economic benefits of treating high-risk hypertension with angiotensin II receptor antagonists (blockers)". Clinical Drug Investigation. 28 (4): 211–20. doi:10.2165/00044011-200828040-00002. PMID 18345711.

External links[แก้]

- Drgarden/ห้องทดลอง3 ที่เว็บไซต์ Curlie