ผลต่างระหว่างรุ่นของ "การอับปางของเรืออาร์เอ็มเอส ไททานิก"

| บรรทัด 106: | บรรทัด 106: | ||

==15 เมษายน 1912== |

==15 เมษายน 1912== |

||

=== เตรียมพร้อมสละเรือ === |

=== เตรียมพร้อมสละเรือ === |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:EJ Smith2.jpg|thumb|alt=Photograph of a bearded man wearing a white captain's uniform with crossed arms|กัปตัน[[เอ็ดเวิร์ด สมิธ|เอ็ดเวิร์ด เจ. สมิธ]] ในปี 1911]] |

||

เมื่อเวลา 00:05 น. ของวันที่ 15 เมษายน กัปตันสมิธสั่งให้เปิดใช้เรือชูชีพและรวมพลผู้โดยสาร{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=22}} นอกจากนี้ เขายังสั่งให้พนักงานวิทยุเริ่มส่งข้อความขอความช่วยเหลือ ข้อความดังกล่าวได้ระบุต่ำแหน่งของเรือผิดพลาดโดยระบุว่าอยู่ด้านตะวันตกของแนวน้ำแข็ง ทำให้ผู้ช่วยเหลือเดินทางไปยังตำแหน่งที่ผิดไปประมาณ 13.5 ไมล์ทะเล (15.5 ไมล์; 25.0 กม.) {{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=199}}{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=120}} ใต้ดาดฟ้าเรือ น้ำได้ไหลลงสู่จุดต่ำสุดของเรือ เช่น ห้องไปรษณีย์ที่ถูกน้ำท่วม ที่ซึ่งพนักงานคัดแยกจดหมายพยายามรักษาไปรษณีย์ 400,000 ชิ้นบน ''ไททานิก'' อย่างสุดความสามารถ ในที่อื่นๆ สามารถได้ยินเสียงอากาศที่ถูกน้ำเข้าแทนที่{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|pp=118–119}} เหนือพื้นที่เหล่านั้น บริกรได้เดินไปตามทางจากประตูสู่ประตู เพื่อปลุกผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือที่นอนหลับและบอกให้พวกเขาขึ้นไปที่ดาดฟ้าเรือ เนื่องจาก ''ไททานิก'' ไม่มีระบบเสียงประกาศสาธารณะ{{sfn|Barczewski|2006|p=20}} |

เมื่อเวลา 00:05 น. ของวันที่ 15 เมษายน กัปตันสมิธสั่งให้เปิดใช้เรือชูชีพและรวมพลผู้โดยสาร{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=22}} นอกจากนี้ เขายังสั่งให้พนักงานวิทยุเริ่มส่งข้อความขอความช่วยเหลือ ข้อความดังกล่าวได้ระบุต่ำแหน่งของเรือผิดพลาดโดยระบุว่าอยู่ด้านตะวันตกของแนวน้ำแข็ง ทำให้ผู้ช่วยเหลือเดินทางไปยังตำแหน่งที่ผิดไปประมาณ 13.5 ไมล์ทะเล (15.5 ไมล์; 25.0 กม.) {{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=199}}{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=120}} ใต้ดาดฟ้าเรือ น้ำได้ไหลลงสู่จุดต่ำสุดของเรือ เช่น ห้องไปรษณีย์ที่ถูกน้ำท่วม ที่ซึ่งพนักงานคัดแยกจดหมายพยายามรักษาไปรษณีย์ 400,000 ชิ้นบน ''ไททานิก'' อย่างสุดความสามารถ ในที่อื่นๆ สามารถได้ยินเสียงอากาศที่ถูกน้ำเข้าแทนที่{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|pp=118–119}} เหนือพื้นที่เหล่านั้น บริกรได้เดินไปตามทางจากประตูสู่ประตู เพื่อปลุกผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือที่นอนหลับและบอกให้พวกเขาขึ้นไปที่ดาดฟ้าเรือ เนื่องจาก ''ไททานิก'' ไม่มีระบบเสียงประกาศสาธารณะ{{sfn|Barczewski|2006|p=20}} |

||

| บรรทัด 131: | บรรทัด 131: | ||

=== การออกเดินทางของเรือชูชีพ === |

=== การออกเดินทางของเรือชูชีพ === |

||

<!--{{further|Lifeboats of the RMS Titanic}} |

<!--{{further|Lifeboats of the RMS Titanic}} |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:Photograph of a Lifeboat Carrying Titanic Survivors - NARA - 278337.jpg|thumb|right|Lifeboat 6 under capacity]] |

||

At 00:45, lifeboat No. 7 was rowed away from ''Titanic'' with 28 passengers on board, despite a capacity of 65. Lifeboat No. 6, on the port side, was the next to be lowered at 00:55. It also had 28 people on board, among them the "unsinkable" [[Margaret Brown|Margaret "Molly" Brown]]. Lightoller realised there was only one seaman on board (Quartermaster Robert Hichens) and called for volunteers. Major [[Arthur Godfrey Peuchen]] of the [[Royal Canadian Yacht Club]] stepped forward and climbed down a rope into the lifeboat; he was the only adult male passenger whom Lightoller allowed to board during the port side evacuation.{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=87}} Peuchen's role highlighted a key problem during the evacuation: there were hardly any seamen to man the boats. Some had been sent below to open gangway doors to allow more passengers to be evacuated, but they never returned. They were presumably trapped and drowned by the rising water below decks.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=150}} |

At 00:45, lifeboat No. 7 was rowed away from ''Titanic'' with 28 passengers on board, despite a capacity of 65. Lifeboat No. 6, on the port side, was the next to be lowered at 00:55. It also had 28 people on board, among them the "unsinkable" [[Margaret Brown|Margaret "Molly" Brown]]. Lightoller realised there was only one seaman on board (Quartermaster Robert Hichens) and called for volunteers. Major [[Arthur Godfrey Peuchen]] of the [[Royal Canadian Yacht Club]] stepped forward and climbed down a rope into the lifeboat; he was the only adult male passenger whom Lightoller allowed to board during the port side evacuation.{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=87}} Peuchen's role highlighted a key problem during the evacuation: there were hardly any seamen to man the boats. Some had been sent below to open gangway doors to allow more passengers to be evacuated, but they never returned. They were presumably trapped and drowned by the rising water below decks.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=150}} |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:The Sad Parting - no caption.jpg|thumb|left|upright|''"The Sad Parting"'', illustration of 1912|alt=Illustration of a weeping woman being comforted by a man on the sloping deck of a ship. In the background men are loading other women into a lifeboat.]] |

||

Meanwhile, other crewmen fought to maintain vital services as water continued to pour into the ship below decks. The engineers and firemen worked to vent steam from the boilers to prevent them from exploding on contact with the cold water. They re-opened watertight doors in order to set up extra portable pumps in the forward compartments in a futile bid to reduce the torrent, and kept the electrical generators running to maintain lights and power throughout the ship. Steward F. Dent Ray narrowly avoided being swept away when a wooden wall between his quarters and the third-class accommodation on E deck collapsed, leaving him waist-deep in water.{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=78}} Two engineers, Herbert Harvey and Jonathan Shepherd (who had just broken his left leg after falling into a manhole minutes earlier), died in boiler room No. 5 when, at around 00:45, the bunker door separating it from the flooded No. 6 boiler room collapsed and they were swept away by "a wave of green foam" according to leading fireman Frederick Barrett, who barely escaped from the boiler room.{{sfn|Halpern|Weeks|2011|p=126}} |

Meanwhile, other crewmen fought to maintain vital services as water continued to pour into the ship below decks. The engineers and firemen worked to vent steam from the boilers to prevent them from exploding on contact with the cold water. They re-opened watertight doors in order to set up extra portable pumps in the forward compartments in a futile bid to reduce the torrent, and kept the electrical generators running to maintain lights and power throughout the ship. Steward F. Dent Ray narrowly avoided being swept away when a wooden wall between his quarters and the third-class accommodation on E deck collapsed, leaving him waist-deep in water.{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=78}} Two engineers, Herbert Harvey and Jonathan Shepherd (who had just broken his left leg after falling into a manhole minutes earlier), died in boiler room No. 5 when, at around 00:45, the bunker door separating it from the flooded No. 6 boiler room collapsed and they were swept away by "a wave of green foam" according to leading fireman Frederick Barrett, who barely escaped from the boiler room.{{sfn|Halpern|Weeks|2011|p=126}} |

||

| บรรทัด 151: | บรรทัด 151: | ||

Much nearer was {{SS|Californian}}, which had warned ''Titanic'' of ice a few hours earlier. Apprehensive at his ship being caught in a large field of drift ice, ''Californian''{{'}}s captain, [[Stanley Lord]], had decided at about 22:00 to halt for the night and wait for daylight to find a way through the ice field.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=159}} At 23:30, 10 minutes before ''Titanic'' hit the iceberg, ''Californian''{{'}}s sole radio operator, [[Cyril Furmstone Evans|Cyril Evans]], shut his set down for the night and went to bed.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=161}} On the bridge her Third Officer, Charles Groves, saw a large vessel to starboard around {{convert|10|to|12|mi|abbr=on}} away. It made a sudden turn to port and stopped. If the radio operator of ''Californian'' had stayed at his post fifteen minutes longer, hundreds of lives might have been saved.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=160}} A little over an hour later, Second Officer Herbert Stone saw five white rockets exploding above the stopped ship. Unsure what the rockets meant, he called Captain Lord, who was resting in the chartroom, and reported the sighting.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=162}} Lord did not act on the report, but Stone was perturbed: "A ship is not going to fire rockets at sea for nothing," he told a colleague.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=163}} |

Much nearer was {{SS|Californian}}, which had warned ''Titanic'' of ice a few hours earlier. Apprehensive at his ship being caught in a large field of drift ice, ''Californian''{{'}}s captain, [[Stanley Lord]], had decided at about 22:00 to halt for the night and wait for daylight to find a way through the ice field.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=159}} At 23:30, 10 minutes before ''Titanic'' hit the iceberg, ''Californian''{{'}}s sole radio operator, [[Cyril Furmstone Evans|Cyril Evans]], shut his set down for the night and went to bed.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=161}} On the bridge her Third Officer, Charles Groves, saw a large vessel to starboard around {{convert|10|to|12|mi|abbr=on}} away. It made a sudden turn to port and stopped. If the radio operator of ''Californian'' had stayed at his post fifteen minutes longer, hundreds of lives might have been saved.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=160}} A little over an hour later, Second Officer Herbert Stone saw five white rockets exploding above the stopped ship. Unsure what the rockets meant, he called Captain Lord, who was resting in the chartroom, and reported the sighting.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=162}} Lord did not act on the report, but Stone was perturbed: "A ship is not going to fire rockets at sea for nothing," he told a colleague.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=163}} |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:Titanic signal.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Distress signal sent at about 01:40 by ''Titanic''{{'}}s radio operator, Jack Phillips, to the [[Russian American Line]] ship SS ''Birma''. This was one of ''Titanic''{{'}}s last intelligible radio messages.|alt=Image of a distress signal reading: "SOS SOS CQD CQD. MGY [Titanic]. We are sinking fast passengers being put into boats. MGY"]] |

||

By this time, it was clear to those on ''Titanic'' that the ship was indeed sinking and there would not be enough lifeboat places for everyone. Some still clung to the hope that the worst would not happen: Lucien Smith told his wife Eloise, "It is only a matter of form to have women and children first. The ship is thoroughly equipped and everyone on her will be saved."{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=84}} Charlotte Collyer's husband Harvey called to his wife as she was put in a lifeboat, "Go, Lottie! For God's sake, be brave and go! I'll get a seat in another boat!"{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=84}} |

By this time, it was clear to those on ''Titanic'' that the ship was indeed sinking and there would not be enough lifeboat places for everyone. Some still clung to the hope that the worst would not happen: Lucien Smith told his wife Eloise, "It is only a matter of form to have women and children first. The ship is thoroughly equipped and everyone on her will be saved."{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=84}} Charlotte Collyer's husband Harvey called to his wife as she was put in a lifeboat, "Go, Lottie! For God's sake, be brave and go! I'll get a seat in another boat!"{{sfn|Lord|1976|p=84}} |

||

| บรรทัด 172: | บรรทัด 172: | ||

==== เรือชูชีพลำสุดท้าย ==== |

==== เรือชูชีพลำสุดท้าย ==== |

||

<!--[[ |

<!--[[ไฟล์:Leaving the sinking liner.jpg|right|thumb|upright|Lifeboat No. 15 was nearly lowered onto lifeboat No. 13 (depicted by [[Charles Dixon (artist)|Charles Dixon]]).|alt=Painting of lifeboats being lowered down the side of Titanic, with one lifeboat about to be lowered on top of another one in the water. A third lifeboat is visible in the background.]] |

||

By 01:30, ''Titanic''{{'}}s downward angle in the water was increasing and the ship was now listing slightly more to port, but not more than 5 degrees. The deteriorating situation was reflected in the tone of the messages sent from the ship: "We are putting the women off in the boats" at 01:25, "Engine room getting flooded" at 01:35, and at 01:45, "Engine room full up to boilers."{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=26}} This was ''Titanic''{{'}}s last intelligible signal, sent as the ship's electrical system began to fail; subsequent messages were jumbled and broken. The two radio operators nonetheless continued sending out distress messages almost to the very end.{{sfn|Regal|2005|p=34}} |

By 01:30, ''Titanic''{{'}}s downward angle in the water was increasing and the ship was now listing slightly more to port, but not more than 5 degrees. The deteriorating situation was reflected in the tone of the messages sent from the ship: "We are putting the women off in the boats" at 01:25, "Engine room getting flooded" at 01:35, and at 01:45, "Engine room full up to boilers."{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=26}} This was ''Titanic''{{'}}s last intelligible signal, sent as the ship's electrical system began to fail; subsequent messages were jumbled and broken. The two radio operators nonetheless continued sending out distress messages almost to the very end.{{sfn|Regal|2005|p=34}} |

||

The remaining boats were filled much closer to capacity and in an increasing rush. No. 11 was filled with five people more than its rated capacity. As it was lowered, it was nearly flooded by water being pumped out of the ship. No. 13 narrowly avoided the same problem but those aboard were unable to release the ropes from which the boat had been lowered. It drifted astern, directly under No. 15 as it was being lowered. The ropes were cut in time and both boats made it away safely.{{sfn|Eaton|Haas|1994|p=153}} |

The remaining boats were filled much closer to capacity and in an increasing rush. No. 11 was filled with five people more than its rated capacity. As it was lowered, it was nearly flooded by water being pumped out of the ship. No. 13 narrowly avoided the same problem but those aboard were unable to release the ropes from which the boat had been lowered. It drifted astern, directly under No. 15 as it was being lowered. The ropes were cut in time and both boats made it away safely.{{sfn|Eaton|Haas|1994|p=153}} |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:Reuterdahl - Sinking of the Titanic.jpg|thumb|left|''"Sinking of the Titanic"'' by [[Henry Reuterdahl]]|alt=Painting of a sinking ship with a lifeboat being rowed away from it in the foreground.]] |

||

The first signs of panic were seen when a group of passengers attempted to rush port-side lifeboat No. 14 as it was being lowered with 40 people aboard. [[Harold Lowe|Fifth Officer Lowe]], who was in charge of the boat, fired three warning shots in the air to control the crowd without causing injuries.{{sfn|Eaton|Haas|1994|p=154}} No. 16 was lowered five minutes later. Among those aboard was stewardess [[Violet Jessop]], who would repeat the experience four years later when she survived the sinking of one of ''Titanic''{{'}}s sister ships, {{HMHS|Britannic||2}}, in the First World War.{{sfn|Eaton|Haas|1994|p=155}} Collapsible boat C was launched at 01:40 from a now largely deserted area of the deck, as most of those on deck had moved to the [[stern]] of the ship. It was aboard this boat that White Star chairman and managing director [[J. Bruce Ismay]], ''Titanic''{{'}}s most controversial survivor, made his escape from the ship, an act later condemned as cowardice.{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=26}} |

The first signs of panic were seen when a group of passengers attempted to rush port-side lifeboat No. 14 as it was being lowered with 40 people aboard. [[Harold Lowe|Fifth Officer Lowe]], who was in charge of the boat, fired three warning shots in the air to control the crowd without causing injuries.{{sfn|Eaton|Haas|1994|p=154}} No. 16 was lowered five minutes later. Among those aboard was stewardess [[Violet Jessop]], who would repeat the experience four years later when she survived the sinking of one of ''Titanic''{{'}}s sister ships, {{HMHS|Britannic||2}}, in the First World War.{{sfn|Eaton|Haas|1994|p=155}} Collapsible boat C was launched at 01:40 from a now largely deserted area of the deck, as most of those on deck had moved to the [[stern]] of the ship. It was aboard this boat that White Star chairman and managing director [[J. Bruce Ismay]], ''Titanic''{{'}}s most controversial survivor, made his escape from the ship, an act later condemned as cowardice.{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=26}} |

||

| บรรทัด 184: | บรรทัด 184: | ||

As passengers and crew headed to the stern, where Father [[Thomas Byles]] was hearing confessions and giving absolutions, ''Titanic''{{'}}s band played outside the gymnasium.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=135}} ''Titanic'' had two separate bands of musicians. One was a quintet led by [[Wallace Hartley]] that played after dinner and at religious services while the other was a trio who played in the reception area and outside the café and restaurant. The two bands had separate music libraries and arrangements and had not played together before the sinking. Around 30 minutes after colliding with the iceberg, the two bands were called by Captain Smith who ordered them to play in the first class lounge. Passengers present remember them playing lively tunes such as "[[Alexander's Ragtime Band]]". It is unknown if the two piano players were with the band at this time. The exact time is unknown, but the musicians later moved to the boat deck level where they played before moving outside onto the deck itself.<ref name=Steph>{{cite book|last1=Barczewski|first1=Stephanie|title=Titanic: A Night Remembered|date=2006|publisher=[[A&C Black]]|isbn=9781852855000|pages=[https://archive.org/details/titanicnightreme0000barc/page/132 132–33]}}</ref> |

As passengers and crew headed to the stern, where Father [[Thomas Byles]] was hearing confessions and giving absolutions, ''Titanic''{{'}}s band played outside the gymnasium.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=135}} ''Titanic'' had two separate bands of musicians. One was a quintet led by [[Wallace Hartley]] that played after dinner and at religious services while the other was a trio who played in the reception area and outside the café and restaurant. The two bands had separate music libraries and arrangements and had not played together before the sinking. Around 30 minutes after colliding with the iceberg, the two bands were called by Captain Smith who ordered them to play in the first class lounge. Passengers present remember them playing lively tunes such as "[[Alexander's Ragtime Band]]". It is unknown if the two piano players were with the band at this time. The exact time is unknown, but the musicians later moved to the boat deck level where they played before moving outside onto the deck itself.<ref name=Steph>{{cite book|last1=Barczewski|first1=Stephanie|title=Titanic: A Night Remembered|date=2006|publisher=[[A&C Black]]|isbn=9781852855000|pages=[https://archive.org/details/titanicnightreme0000barc/page/132 132–33]}}</ref> |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:Nearer My God To Thee Titanic - no caption.png|thumb|''"Nearer, My God, To Thee"'' – cartoon of 1912|alt=Cartoon depicting a man standing with a woman, who is hiding her head on his shoulder, on the deck of a ship awash with water. A beam of light is shown coming down from heaven to illuminate the couple. Behind them is an empty davit.]] |

||

Part of the enduring folklore of the ''Titanic'' sinking is that the musicians played the hymn "[[Nearer, My God, to Thee]]" as the ship sank, but this appears to be dubious.{{sfn|Howells|1999|p=128}} The claim surfaced among the earliest reports of the sinking,{{sfn|Howells|1999|p=129}} and the hymn became so closely associated with the ''Titanic'' disaster that its opening bars were carved on the grave monument of ''Titanic''{{'}}s bandmaster, Wallace Hartley, one of those who perished.{{sfn|Richards|2001|p=395}} Violet Jessop said in her 1934 account of the disaster that she had heard the hymn being played.{{sfn|Howells|1999|p=128}} In contrast, Archibald Gracie emphatically denied it in his own account, written soon after the sinking, and Radio Operator Harold Bride said that he had heard the band playing ragtime, then "Autumn",{{sfn|Richards|2001|p=396}} by which he may have meant [[Archibald Joyce]]'s then-popular waltz "Songe d'Automne" (Autumn Dream). George Orrell, the bandmaster of the rescue ship, ''Carpathia'', who spoke with survivors, related: "The ship's band in any emergency is expected to play to calm the passengers. After ''Titanic'' struck the iceberg the band began to play bright music, dance music, comic songs – anything that would prevent the passengers from becoming panic-stricken ... various awe-stricken passengers began to think of the death that faced them and asked the bandmaster to play hymns. The one which appealed to all was 'Nearer My God to Thee'."{{sfn|Turner|2011|p=194}} According to Gracie, who was near the band until that section of deck went under, the tunes played by the band were "cheerful" but he didn't recognise any of them, claiming that if they had played 'Nearer, My God, to Thee' as claimed in the newspaper "I assuredly should have noticed it and regarded it as a tactless warning of immediate death to us all and one likely to create panic."{{sfn|Gracie|1913|p=20}} Several survivors who were among the last to leave the ship claimed that the band continued playing until the slope of the deck became too steep for them to stand, Gracie claimed that the band stopped playing at least 30 minutes before the vessel sank. Several witnesses support this account including A. H. Barkworth, a first-class passenger who testified: "I do not wish to detract from the bravery of anybody, but I might mention that when I first came on deck the band was playing a waltz. The next time I passed where the band was stationed, the members had thrown down their instruments and were not to be seen."<ref name="Steph"/> |

Part of the enduring folklore of the ''Titanic'' sinking is that the musicians played the hymn "[[Nearer, My God, to Thee]]" as the ship sank, but this appears to be dubious.{{sfn|Howells|1999|p=128}} The claim surfaced among the earliest reports of the sinking,{{sfn|Howells|1999|p=129}} and the hymn became so closely associated with the ''Titanic'' disaster that its opening bars were carved on the grave monument of ''Titanic''{{'}}s bandmaster, Wallace Hartley, one of those who perished.{{sfn|Richards|2001|p=395}} Violet Jessop said in her 1934 account of the disaster that she had heard the hymn being played.{{sfn|Howells|1999|p=128}} In contrast, Archibald Gracie emphatically denied it in his own account, written soon after the sinking, and Radio Operator Harold Bride said that he had heard the band playing ragtime, then "Autumn",{{sfn|Richards|2001|p=396}} by which he may have meant [[Archibald Joyce]]'s then-popular waltz "Songe d'Automne" (Autumn Dream). George Orrell, the bandmaster of the rescue ship, ''Carpathia'', who spoke with survivors, related: "The ship's band in any emergency is expected to play to calm the passengers. After ''Titanic'' struck the iceberg the band began to play bright music, dance music, comic songs – anything that would prevent the passengers from becoming panic-stricken ... various awe-stricken passengers began to think of the death that faced them and asked the bandmaster to play hymns. The one which appealed to all was 'Nearer My God to Thee'."{{sfn|Turner|2011|p=194}} According to Gracie, who was near the band until that section of deck went under, the tunes played by the band were "cheerful" but he didn't recognise any of them, claiming that if they had played 'Nearer, My God, to Thee' as claimed in the newspaper "I assuredly should have noticed it and regarded it as a tactless warning of immediate death to us all and one likely to create panic."{{sfn|Gracie|1913|p=20}} Several survivors who were among the last to leave the ship claimed that the band continued playing until the slope of the deck became too steep for them to stand, Gracie claimed that the band stopped playing at least 30 minutes before the vessel sank. Several witnesses support this account including A. H. Barkworth, a first-class passenger who testified: "I do not wish to detract from the bravery of anybody, but I might mention that when I first came on deck the band was playing a waltz. The next time I passed where the band was stationed, the members had thrown down their instruments and were not to be seen."<ref name="Steph"/> |

||

| บรรทัด 190: | บรรทัด 190: | ||

Archibald Gracie was also heading aft, but as he made his way towards the stern he found his path blocked by "a mass of humanity several lines deep, covering the boat deck, facing us"{{sfn|Winocour|1960|pp=138–39}} – hundreds of steerage passengers, who had finally made it to the deck just as the last lifeboats departed. He gave up on the idea of going aft and jumped into the water to get away from the crowd.{{sfn|Winocour|1960|pp=138–39}} Others made no attempt to escape. |

Archibald Gracie was also heading aft, but as he made his way towards the stern he found his path blocked by "a mass of humanity several lines deep, covering the boat deck, facing us"{{sfn|Winocour|1960|pp=138–39}} – hundreds of steerage passengers, who had finally made it to the deck just as the last lifeboats departed. He gave up on the idea of going aft and jumped into the water to get away from the crowd.{{sfn|Winocour|1960|pp=138–39}} Others made no attempt to escape. |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:Titanic the sinking.jpg|thumb|Illustration of the sinking of the ''Titanic'']]--> |

||

=== นาทีสุดท้ายก่อนอับปาง === |

=== นาทีสุดท้ายก่อนอับปาง === |

||

| บรรทัด 206: | บรรทัด 206: | ||

==== วาระสุดท้ายของ ''ไททานิก'' ==== |

==== วาระสุดท้ายของ ''ไททานิก'' ==== |

||

<!--[[ |

<!--[[ไฟล์:Titanic's sinking stern.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Imagined view of ''Titanic''{{'s}} final plunge]] |

||

''Titanic'' was subjected to extreme opposing forces – the flooded bow pulling her down while the air in the stern kept her to the surface – which were concentrated at one of the weakest points in the structure, the area of the engine room hatch. Shortly after the lights went out, the ship split apart. The submerged bow may have remained attached to the stern by the keel for a short time, pulling the stern to a high angle before separating and leaving the stern to float for a few moments longer. The forward part of the stern would have flooded very rapidly, causing it to tilt and then settle briefly until sinking.{{sfn|Halpern|Weeks|2011|p=119}}{{sfn|Barczewski|2006|p=29}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://video.nationalgeographic.com/tv/00000144-2f3a-df5d-abd4-ff7f31f90000|title=Titanic Sinking CGI|publisher=National Geographic Channel|accessdate=17 February 2016}}</ref> The ship disappeared from view at 02:20, 2 hours and 40 minutes after striking the iceberg. Thayer reported that it rotated on the surface, "gradually [turning] her deck away from us, as though to hide from our sight the awful spectacle ... Then, with the deadened noise of the bursting of her last few gallant bulkheads, she slid quietly away from us into the sea."{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=29}} |

''Titanic'' was subjected to extreme opposing forces – the flooded bow pulling her down while the air in the stern kept her to the surface – which were concentrated at one of the weakest points in the structure, the area of the engine room hatch. Shortly after the lights went out, the ship split apart. The submerged bow may have remained attached to the stern by the keel for a short time, pulling the stern to a high angle before separating and leaving the stern to float for a few moments longer. The forward part of the stern would have flooded very rapidly, causing it to tilt and then settle briefly until sinking.{{sfn|Halpern|Weeks|2011|p=119}}{{sfn|Barczewski|2006|p=29}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://video.nationalgeographic.com/tv/00000144-2f3a-df5d-abd4-ff7f31f90000|title=Titanic Sinking CGI|publisher=National Geographic Channel|accessdate=17 February 2016}}</ref> The ship disappeared from view at 02:20, 2 hours and 40 minutes after striking the iceberg. Thayer reported that it rotated on the surface, "gradually [turning] her deck away from us, as though to hide from our sight the awful spectacle ... Then, with the deadened noise of the bursting of her last few gallant bulkheads, she slid quietly away from us into the sea."{{sfn|Ballard|1987|p=29}} |

||

| บรรทัด 216: | บรรทัด 216: | ||

=== ผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือในน้ำ === |

=== ผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือในน้ำ === |

||

<!--[[ |

<!--[[ไฟล์:Titanic watch.jpg|thumb|Pocket watch retrieved from the wreck site, stopped showing a time of 2:28|alt=Photograph of a brass pocket watch on a stand, with a silver chain curled around the base. The watch's hands read 2:28.]] |

||

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, hundreds of passengers and crew were left dying in the icy sea, surrounded by debris from the ship. ''Titanic''{{'}}s disintegration during her descent to the seabed caused buoyant chunks of debris – timber beams, wooden doors, furniture, panelling and chunks of cork from the bulkheads – to rocket to the surface. These injured and possibly killed some of the swimmers; others used the debris to try to keep themselves afloat.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=139}} |

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, hundreds of passengers and crew were left dying in the icy sea, surrounded by debris from the ship. ''Titanic''{{'}}s disintegration during her descent to the seabed caused buoyant chunks of debris – timber beams, wooden doors, furniture, panelling and chunks of cork from the bulkheads – to rocket to the surface. These injured and possibly killed some of the swimmers; others used the debris to try to keep themselves afloat.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=139}} |

||

| บรรทัด 226: | บรรทัด 226: | ||

The noise of the people in the water screaming, yelling, and crying was a tremendous shock to the occupants of the lifeboats, many of whom had up to that moment believed that everyone had escaped before the ship sank. As Beesley later wrote, the cries "came as a thunderbolt, unexpected, inconceivable, incredible. No one in any of the boats standing off a few hundred yards away can have escaped the paralysing shock of knowing that so short a distance away a tragedy, unbelievable in its magnitude, was being enacted, which we, helpless, could in no way avert or diminish."{{sfn|Barratt|2010|pp=199–200}} |

The noise of the people in the water screaming, yelling, and crying was a tremendous shock to the occupants of the lifeboats, many of whom had up to that moment believed that everyone had escaped before the ship sank. As Beesley later wrote, the cries "came as a thunderbolt, unexpected, inconceivable, incredible. No one in any of the boats standing off a few hundred yards away can have escaped the paralysing shock of knowing that so short a distance away a tragedy, unbelievable in its magnitude, was being enacted, which we, helpless, could in no way avert or diminish."{{sfn|Barratt|2010|pp=199–200}} |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:Archibald Gracie IV.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Archibald Gracie IV|Colonel Archibald Gracie]], one of the survivors who made it to collapsible lifeboat B. He never recovered from his ordeal and died eight months after the sinking.|alt=Photograph of a moustached middle-aged man in a dark suit and waistcoat, sitting in a chair while looking at the camera]] |

||

Only a few of those in the water survived. Among them were Archibald Gracie, Jack Thayer and Charles Lightoller, who made it to the capsized collapsible boat B. Around 12 crew members climbed on board Collapsible B, and they rescued those they could until some 35 men were clinging precariously to the upturned hull. Realising the risk to the boat of being swamped by the mass of swimmers around them, they paddled slowly away, ignoring the pleas of dozens of swimmers to be allowed on board. In his account, Gracie wrote of the admiration he had for those in the water; "In no instance, I am happy to say, did I hear any word of rebuke from a swimmer because of a refusal to grant assistance... [one refusal] was met with the manly voice of a powerful man... 'All right boys, good luck and God bless you'."{{sfn|Gracie|1913|p=89}} Several other swimmers (probably 20 or more) reached Collapsible boat A, which was upright but partly flooded, as its sides had not been properly raised. Its occupants had to sit for hours in a foot of freezing water,{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=224}} and many died of hypothermia during the night. |

Only a few of those in the water survived. Among them were Archibald Gracie, Jack Thayer and Charles Lightoller, who made it to the capsized collapsible boat B. Around 12 crew members climbed on board Collapsible B, and they rescued those they could until some 35 men were clinging precariously to the upturned hull. Realising the risk to the boat of being swamped by the mass of swimmers around them, they paddled slowly away, ignoring the pleas of dozens of swimmers to be allowed on board. In his account, Gracie wrote of the admiration he had for those in the water; "In no instance, I am happy to say, did I hear any word of rebuke from a swimmer because of a refusal to grant assistance... [one refusal] was met with the manly voice of a powerful man... 'All right boys, good luck and God bless you'."{{sfn|Gracie|1913|p=89}} Several other swimmers (probably 20 or more) reached Collapsible boat A, which was upright but partly flooded, as its sides had not been properly raised. Its occupants had to sit for hours in a foot of freezing water,{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=224}} and many died of hypothermia during the night. |

||

| บรรทัด 238: | บรรทัด 238: | ||

=== การช่วยชีวิตและการออกเดินทาง === |

=== การช่วยชีวิตและการออกเดินทาง === |

||

[[ |

[[ไฟล์:Titanic lifeboat.jpg|thumb|เรือชูชีพพับได้ ดี ถ่ายจากดาดฟ้าเรือ ''คาร์เพเทีย'' ในตอนเช้าวันที่ 15 เมษายน 1912|alt=Photograph of a lifeboat, filled with people wearing life jackets, being rowed towards the camera.]] |

||

ผู้รอดชีวิตของเรือ ''ไททานิก'' ได้รับการช่วยเหลือในเวลาประมาณ 04:00 น. วันที่ 15 เมษายนโดย[[อาร์เอ็มเอส คาร์เพเทีย]] ที่แล่นด้วยความเร็วเต็มที่มาตลอดคืนบนเส้นทางเสี่ยงอันตราย ซึ่งเรือต้องเลี้ยวหลบภูเขาน้ำแข็งหลายลูกตลอดเส้นทางมายังจุดอับปาง{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=238}} แสงไฟจาก ''คาร์เพเทีย'' ถูกพบครั้งแรกราวเวลา 03:30 น.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=238}} ซึ่งสร้างกำลังใจให้ผู้รอดชีวิตเป็นอย่างมาก แม้ว่าจะต้องใช้เวลาอีกหลายชั่วโมงกว่าที่ทุกคนจะถูกพาขึ้นเรือ <!--The 30 or more men on collapsible B finally managed to board two other lifeboats, but one survivor died just before the transfer was made.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|pp=240–41}} Collapsible A was also in trouble and was now nearly awash; many of those aboard (maybe more than half) had died overnight.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=140}} The remaining survivors – an unknown number of men, estimated to be between 10–11 and more than 20, and one woman – were transferred from A into another lifeboat, leaving behind three bodies in the boat, which was left to drift away. It was recovered a month later by the White Star liner {{RMS|Oceanic|1899|6}} with the bodies still aboard.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|pp=240–41}} |

ผู้รอดชีวิตของเรือ ''ไททานิก'' ได้รับการช่วยเหลือในเวลาประมาณ 04:00 น. วันที่ 15 เมษายนโดย[[อาร์เอ็มเอส คาร์เพเทีย]] ที่แล่นด้วยความเร็วเต็มที่มาตลอดคืนบนเส้นทางเสี่ยงอันตราย ซึ่งเรือต้องเลี้ยวหลบภูเขาน้ำแข็งหลายลูกตลอดเส้นทางมายังจุดอับปาง{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=238}} แสงไฟจาก ''คาร์เพเทีย'' ถูกพบครั้งแรกราวเวลา 03:30 น.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=238}} ซึ่งสร้างกำลังใจให้ผู้รอดชีวิตเป็นอย่างมาก แม้ว่าจะต้องใช้เวลาอีกหลายชั่วโมงกว่าที่ทุกคนจะถูกพาขึ้นเรือ <!--The 30 or more men on collapsible B finally managed to board two other lifeboats, but one survivor died just before the transfer was made.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|pp=240–41}} Collapsible A was also in trouble and was now nearly awash; many of those aboard (maybe more than half) had died overnight.{{sfn|Butler|1998|p=140}} The remaining survivors – an unknown number of men, estimated to be between 10–11 and more than 20, and one woman – were transferred from A into another lifeboat, leaving behind three bodies in the boat, which was left to drift away. It was recovered a month later by the White Star liner {{RMS|Oceanic|1899|6}} with the bodies still aboard.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|pp=240–41}} |

||

รุ่นแก้ไขเมื่อ 02:59, 23 กุมภาพันธ์ 2564

"Untergang der Titanic" โดยวิลลี่ สโตเวอร์ (Willy Stöwer), 1912 | |

| วันที่ | 14–15 เมษายน 1912 |

|---|---|

| เวลา | 23:40–02:20 (02:38–05:18 GMT)[a] |

| ระยะเวลา | 2 ชั่วโมง 40 นาที |

| ที่ตั้ง | มหาสมุทรแอตแลนติก, 400 ไมล์ (640 กิโลเมตร) ทางตะวันออกของนิวฟันด์แลนด์ |

| พิกัด | 41°43′32″N 49°56′49″W / 41.72556°N 49.94694°W |

| ประเภท | ภัยพิบัติทางทะเล |

| สาเหตุ | ชนภูเขาน้ำแข็งในวันที่ 14 เมษายน |

| ผู้เข้าร่วม | ลูกเรือและผู้โดยสาร |

| ผล | การเปลี่ยนแปลงนโยบายทางทะเล SOLAS |

| เสียชีวิต | 1,490–1,635 |

อาร์เอ็มเอส ไททานิก จมลงในเวลาเช้าตรู่ของวันที่ 15 เมษายน 1912 ในมหาสมุทรแอตแลนติก วันที่สี่ในการเดินทางครั้งแรกของเรือจากเซาแทมป์ตันไปนครนิวยอร์ก ไททานิก เป็นเรือเดินสมุทรที่ใหญ่ที่สุดที่ให้บริการในเวลานั้น เรือชนกับภูเขาน้ำแข็งเมื่อเวลาราว 23:40 (เวลาเดินเรือ)[a] ในวันอาทิตย์ที่ 14 เมษายน 1912 เรือจมลงในเวลาสองชั่วโมงสี่สิบนาทีต่อมา เมื่อเวลา 02:20 น. (เวลาเดินเรือ; 05:18 GMT) ในวันจันทร์ที่ 15 เมษายน ส่งผลให้มีผู้เสียชีวิตมากกว่า 1,500 คน จากคนบนเรือประมาณ 2,224 คน ทำให้เหตุการณ์นี้เป็นหนึ่งในภัยพิบัติทางทะเลที่ร้ายแรงที่สุดในประวัติศาสตร์

วันที่ 14 เมษายน ไททานิก ได้รับคำเตือนหกครั้งเกี่ยวกับก้อนน้ำแข็งในทะเล แต่ด้วยความเร็วประมาณ 22 นอต ทำให้เมื่อเรือมองภูเขาน้ำแข็ง เรือจึงไม่สามารถเลี้ยวหลบได้ทัน ส่งผลให้เรือได้รับความเสียหายจากการชนแฉลบที่กราบขวาของเรือ และสร้างรอยรั่วในหกห้องจากสิบหกห้องเรือ (ส่วนหน้าสุดของหัวเรือ, ห้องว่างสามห้อง, และห้องหม้อไอน้ำหมายเลข 5 และ 6) ไททานิก ได้รับการออกแบบให้ลอยอยู่ได้เมื่อห้องเรือด้านหัวเรือสี่ห้องถูกน้ำท่วมเท่านั้น และในไม่ช้าลูกเรือก็ตระหนักว่าเรือกำลังจะจม พวกเขาใช้พลุแฟลร์และส่งข้อความทางวิทยุโทรเลข เพื่อขอความช่วยเหลือ ขณะที่ผู้โดยสารถูกนำไปยังเรือชูชีพ

ตามแนวทางปฏิบัติที่มีอยู่ ระบบเรือชูชีพของไททานิคได้รับการออกแบบมาเพื่อให้ผู้โดยสารข้ามไปยังเรือกู้ภัยใกล้เคียง ไม่ใช่ให้ทุกคนอยู่บนเรือชูชีพในเวลาเดียวกัน ดังนั้น ด้วยการที่เรือจมลงอย่างรวดเร็ว และชั่วโมงทองในการช่วยเหลือได้ผ่านพ้นไปแล้ว ไม่มีอุปกรณ์ช่วยเหลือที่ปลอดภัยเพียงพอสำหรับผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือจำนวนมาก ด้วยเหตุเหล่านี้ ทำให้การจัดการการอพยพย่ำแย่อย่างมาก มีการปล่อยเรือชูชีพจำนวนมากก่อนที่เรือจะเต็ม

ด้วยเหตุที่ เมื่อ ไททานิก จมยังมีผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือมากกว่าพันคนบนเรือ ทำให้คนที่กระโดดหรือตกลงไปในน้ำ เกือบทุกคนจมน้ำตายหรือเสียชีวิตภายในไม่กี่นาทีเนื่องจากผลของสภาวะช็อกจากความเย็นและสูญเสียความสามารถจากความเย็น อาร์เอ็มเอส คาร์เพเทีย มาถึงที่เกิดเหตุประมาณหนึ่งชั่วโมงครึ่งหลังจากเรือจม และช่วยผู้รอดชีวิตคนสุดท้ายในเวลา 09:15 น. ในวันที่ 15 เมษายน ราวเก้าชั่วโมงครึ่งหลังจากการชนภูเขาน้ำแข็ง ภัยพิบัติดังกล่าวทำให้โลกตื่นตะหนกและทำให้เกิดความโกรธแค้นอย่างกว้างขวางเนื่องจากเรือชูชีพไม่เพียงพอ กฎระเบียบที่หละหลวม และการปฏิบัติต่อผู้โดยสารทั้งสามชั้นที่ไม่เท่าเทียมกันในระหว่างการอพยพ การไต่สวนในภายหลังสนับสนุนการเปลี่ยนแปลงที่ครอบคลุมของกฎระเบียบทางทะเล นำไปสู่การจัดตั้งในปี 1914 ของอนุสัญญาระหว่างประเทศว่าด้วยความปลอดภัยแห่งชีวิตในทะเล (SOLAS)

พื้นหลัง

เรือเข้าประจำการในวันที่ 2 เมษายน 1912 โรยัล เมล ชิป (อาร์เอ็มเอส) ไททานิก เป็นเรือลำที่สองจากสามลำ[b] ในเรือเดินสมุทรชั้นโอลิมปิก และเป็นเรือที่มีขนาดใหญ่ที่สุดในโลก ณ ขณะนั้น ไททานิก และเรือพี่น้อง อาร์เอ็มเอส โอลิมปิก มีระวางน้ำหนักเรือเป็นเท่าครึ่งของ อาร์เอ็มเอส ลูซิเทเนีย และ อาร์เอ็มเอส มอริเตเนีย ของสายการเดินเรือคูนาร์ด ซึ่งถือครองสถิติก่อนหน้า และยาวกว่าเกือบ 100 ฟุต (30 เมตร)[2] ไททานิก สามารถบรรทุกคนได้ถึง 3,547 คนและยังคงความเร็วและความสบายไว้ได้[3] และถูกสร้างขึ้นด้วยขนาดที่ไม่เคยมีมาก่อน มีเครื่องยนต์ลูกสูบใหญ่ที่สุดที่เคยสร้างมา สูง 40 ฟุต (12 เมตร) กระบอกสูบมีเส้นผ่านศูนย์กลาง 9 ฟุต (2.7 เมตร) ต้องเผาถ่านหิน 610 ตันต่อวันเป็นเชื้อเพลิง[3]

ที่พักผู้โดยสารบนเรือ โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในส่วนชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาส พูดได้ว่าเป็น "ความเหนือชั้นและความโอ่อ่างดงาม"[4] สังเกตได้จากค่าโดยสารที่พักชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาส ห้องพาร์เลอะสวีท (ห้องชุดที่แพงที่สุดและหรูหราที่สุดบนเรือ) พร้อมดาดฟ้าเดินเล่นส่วนตัวมีราคาสูงกว่า $4,350 (เทียบเท่ากับ $115,000 ในปัจจุบัน)[5] สำหรับข้ามมหาสมุทรแอตแลนติกเที่ยวเดียว แม้แต่ชั้นสามแม้จะมีความหรูหราน้อยกว่าชั้นสองและเฟิร์สต์คลาสมาก แต่ก็สบายกว่ามาตรฐานร่วมสมัยและได้รับอาหารอร่อยมากมาย ทำให้ผู้โดยสารบนเรือหลายคนมีสภาพความเป็นอยู่ที่ดีกว่าเคยมีประสบการณ์ในบ้านของตน[4]

การเดินทางครั้งแรกของ ไททานิก เริ่มขึ้นหลังเที่ยงวันที่ 10 เมษายน 1912 เมื่อเรือออกจากเซาแทมป์ตันที่เป็นขาแรกของการเดินทางสู่นิวยอร์ก[6] ไม่กี่ชั่วโมงต่อมาเรือแวะไปที่แชร์บูร์กทางตอนเหนือของฝรั่งเศส ระยะทาง 80 ไมล์ทะเล (148 กิโลเมตร; 92 ไมล์) เพื่อรับผู้โดยสาร[7] ท่าเรือถัดไปคือควีนส์ทาวน์ (หรือโคฟในปัจจุบัน) ในไอร์แลนด์ ซึ่งเรือเดินทางมาถึงตอนเที่ยงวันที่ 11 เมษายน[8] เรือออกเดินทางตอนบ่ายหลังจากรับผู้โดยสารและสินค้าค้าเพิ่มเติม[9]

เมื่อถึงเวลา เรือบ่ายหน้ามุ่งไปทางตะวันตกข้ามมหาสมุทรแอตแลนติก บนเรือมีลูกเรือ 892 คนและผู้โดยสาร 1,320 คน ซึ่งเป็นเพียงครึ่งหนึ่งของผู้โดยสารเต็มความจุของของเรือ หรือ 2,435 คน[10] เนื่องจากเป็นช่วงนอกฤดูท่องเที่ยวและการขนส่งจากสหราชอาณาจักรถูกรบกวนจากการประท้วงของคนงานเหมืองถ่านหิน[11] ผู้โดยสารของเรือเป็นเสมือนภาคตัดขวางของสังคมเอ็ดเวิร์ด มีตั้งแต่มหาเศรษฐีเช่น จอห์น เจคอบ แอสเตอร์ (John Jacob Astor) และ เบนจามิน กุกเกนไฮม์ (Benjamin Guggenheim)[12] ไปจนถึงผู้อพยพยากจนจากประเทศต่างๆ เช่น อาร์เมเนีย, ไอร์แลนด์, อิตาลี, สวีเดน, ซีเรีย และรัสเซีย ที่ต้องการไปแสวงหาชีวิตใหม่ในสหรัฐอเมริกา[13]

เรือมีเอ็ดเวิร์ด สมิธ กัปตันอาวุโสของไวต์สตาร์ไลน์วัย 62 ปีเป็นหัวหน้าควบคุมเรือ เขามีประสบการณ์การเดินเรือถึงสี่ทศวรรษ และทำหน้าที่เป็นกัปตันของ อาร์เอ็มเอส โอลิมปิก มาก่อนที่จะย้ายมาควบคุมเรือ ไททานิก[14] ลูกเรือส่วนมากไม่เคยรับการฝึกมาก่อน ทั้ง นายช่าง เจ้าหน้าที่ดับเพลิง หรือ พนักงานควบคุมเตาไฟ ที่มีหน้าที่ดูแลเครื่องยนต์ หรือบริกร และพนักงานห้องครัวที่มีหน้าที่ดูแลต่อผู้โดยสาร มีนายยามเรือเดิน 6 คนและกลาสีชำนาญงาน 39 คน หรือประมาณ 5% จากลูกเรือทั้งหมดเท่านั้น[10] และส่วนใหญ่ขึ้นเรือที่เซาแทมป์ตันจึงไม่มีเวลาทำความคุ้นเคยกับเรือ[15]

ก่อนออกเดินทางประมาณ 10 วัน เกิดไฟไหม้ที่ยุ้งถ่านหินยุ้งหนึ่งของ ไททานิก และไหม้ต่อเนื่องไปอีกหลายวันระหว่างการเดินทาง แต่ในวันที่ 14 เมษายนได้ดับไฟเป็นที่เรียบร้อยแล้ว[16][17] สภาพอากาศดีขึ้นอย่างมากในระหว่างวัน จากลมแรงและทะเลปานกลางในตอนเช้า กลายเป็นทะเลสงบในตอนเย็น ขณะที่เส้นทางพาเรือไปอยู่ภายใต้ความกดอากาศสูงของขั้วโลกเหนือ[18]

ในช่วงเวลานั้น เนื่องด้วยหน้าหนาวที่ไม่หนาวรุนแรงทำให้ภูเขาน้ำแข็งจำนวนมากเคลื่อนตัวหลุดออกจากชายฝั่งตะวันตกของกรีนแลนด์[19]

14 เมษายน 1912

คำเตือน "ภูเขาน้ำแข็ง"

ในวันที่ 14 เมษายน 1912 พนักงานวิทยุ[c]ของ ไททานิก ได้รับหกข้อความจากเรือลำอื่นเรื่องภูเขาน้ำแข็งที่ลอยอยู่ในทะเล และผู้โดยสารบนเรือ ไททานิก ก็เริ่มสังเกตเห็นในช่วงบ่ายวันนั้น ในเวลานั้นพนักงานวิทยุทั้งหมดในเรือเดินสมุทรเป็นพนักงานของบริษัทโทรเลขไร้สายของมาร์โคนีและไม่ใช่ลูกเรือ ความรับผิดชอบหลักของพนักงานคือการส่งข้อความให้ผู้โดยสาร สำหรับรายงานสภาพอากาศเป็นเรื่องรอง อีกทั้ง สภาพน้ำแข็งในแอตแลนติกเหนือนั้นเลวร้ายที่สุดในเดือนเมษายนเกิดขึ้นเมื่อ 50 ปีมาแล้ว (ซึ่งเป็นเหตุผลว่าทำไมการพนักงานเฝ้าระวังไม่ทราบว่าเลยว่าพวกเขากำลังจะแล่นเรือเข้าไปในแนวน้ำแข็งที่ทอดยาวหลายไมล์)[20]

ข้อความแรกมาจากเรือ อาร์เอ็มเอส คาโรเนีย (RMS Caronia) เมื่อ 09:00 รายงานว่า "ภูเขาน้ำแข็ง, ชิ้นน้ำแข็ง[d] และทุ่งน้ำแข็ง"[21] กัปตันสมิธรับทราบข้อความ เมื่อเวลา 13:42 เรือ อาร์เอ็มเอส บอลติก (RMS Baltic) ส่งรายงานจากเรือกรีก อาธีเนีย (Athenia) ว่าเรือ "แล่นผ่านภูเขาน้ำแข็งและทุ่งน้ำแข็งขนาดใหญ่"[21] ข้อความนี้รับทราบโดยกัปตันสมิธเช่นกัน และรายงานถึง เจ. บรูซ อิสเมย์ (J. Bruce Ismay) ประธานของไวต์สตาร์ไลน์ ซึ่งอยู่บนเรือ ไททานิก[21] กัปตันสมิธสั่งให้มีการกำหนดเส้นทางใหม่ ให้แล่นเรือไกลออกไปทางใต้[22]

เมื่อเวลา 13:45 เราเยอรมัน เอสเอส อเมอริกา (SS Amerika) ซึ่งอยู่ห่างไปทางใต้ไม่ไกลจาก ไททานิก รายงานว่าเรือ "แล่นผ่านภูเขาน้ำแข็งขนาดใหญ่สองลูก"[23] แต่ข้อความนี้ไม่เคยไปถึงกัปตันสมิธ หรือเจ้าหน้าที่คนอื่นๆบนสะพานเดินเรือ เหตุผลนั้นไม่ชัดเจน แต่อาจเป็นเพราะถูกลืมเพราะพนักงานวิทยุมัวแต่ซ่อมอุปกรณ์ที่เสียอยู่[23]

เรือ เอสเอส คาลิฟอร์เนียน (SS Californian) รายงานว่า "ภูเขาน้ำแข็งขนาดใหญ่สามลูก" เมื่อเวลา 19:30 และเมื่อเวลา 21:40 เรือกลไฟ เมซาบา (Mesaba) รายงานว่า "มองเห็นก้อนน้ำแข็งและภูเขาน้ำแข็งขนาดใหญ่จำนวนมาก รวมทั้งทุ่งน้ำแข็งด้วย"[24] แต่ข้อความเหล่านี้ไม่ได้ถูกส่งออกจากห้องวิทยุของ ไททานิก พนักงานวิทยุ แจ็ค ฟิลลิปส์ (Jack Phillips) นั้นอาจไม่เข้าใจถึงความสำคัญของข้อความเหล่านี้ เพราะเขาหมกมุ่นอยู่กับการส่งข้อความให้ผู้โดยสารผ่านทางสถานีถ่ายทอดที่เคปเรส นิวฟันด์แลนด์ เนื่องจากชุดวิทยุพังลงเมื่อวันก่อน ส่งผลให้มีข้อความคั่งค้างที่พนักงานทั้งสองรายพยายามที่จะจัดการให้เสร็จ[23] คำเตือนสุดท้ายได้รับเมื่อเวลา 22:30 จากพนักงานวิทยุ ซีริล อีวานส์ (Cyril Evans) ของ เรือคาลิฟอร์เนียน ที่หยุดเรือในคืนนี้ในทุ่งน้ำแข็งห่างออกไปหลายไมล์ แต่ฟิลลิปส์ตัดการสื่อสารออกแล้วส่งสัญญาณกลับ: "หุบปาก! หุบปาก! ฉันกำลังสื่อสารกับเคปเรสอยู่"[24]

แม้ว่าลูกเรือจะรับรู้ถึงน้ำแข็งในบริเวณใกล้เคียงกับเรือ แต่พวกเขาก็ไม่ได้ลดความเร็วของเรือลงและยังคงแล่นที่ 22 นอต (41 กม./ชม.; 25 ไมล์ต่อชั่วโมง) ซึ่งห่างจากความเร็วสูงสุดของเรือเพียง 2 นอต (3.7 กม./ชม.; 2.3 ไมล์ต่อชั่วโมง)[23][e] การแล่นเรือด้วยความเร็วสูงในทะเลที่เต็มไปด้วยน้ำแข็งของ ไททานิก นั้น ภายหลังถูกวิพากษ์วิจารณ์ว่าสะเพร่าไม่ยั้งคิด แต่มันสะท้อนให้เห็นถึงการปฏิบัติตามมาตรฐานการเดินเรือในเวลานั้น อ้างอิงถึงต้นเรือที่ห้า แฮโรลด์ โลว์ (Harold Lowe) ที่กล่าวว่าธรรมเนียมปฏิบัติคือ "แล่นไปข้างหน้า และไว้ใจพนักงานเฝ้าระวังในรังกาและนายยามเรือเดินบนสะพานเดินเรือที่คอยมองหาก้อนน้ำแข็งเพื่อหลีกเลี่ยงการชน"[26]

เรือเดินสมุทรสายแอตแลนติกเหนือจัดลำดับความสำคัญของการรักษาเวลาไว้เหนือข้อควรพิจารณาอื่นๆทั้งหมด ยึดติดกับตารางการเดินทางที่จะรับประกันการเดินถึงปลายทางตามในเวลาที่โฆษณา พวกเขาเดินเรือด้วยความเร็วเกือบเต็มที่ การปฏิบัติตามคำเตือนถึงอันตรายเป็นเพียงคำแนะนำแทนที่จะเป็นข้อปฏิบัติที่ต้องดำเนินการ เป็นความเชื่อกันอย่างกว้างขวางว่าก้อนน้ำแข็งสร้างความเสี่ยงเพียงเล็กน้อย เฉียดฉิวก็ไม่ใช่เรื่องแปลก ชนประสานงาก็ไม่ใช่หายนะ ในปี 1907 เรือ เอสเอส โครนพรินซ์ วิลเฮ็ล์ม (SS Kronprinz Wilhelm) ของสายการเดินเรือเยอรมันชนกับภูเขาน้ำแข็งและทำให้หัวเรือแตก แต่ก็ยังคงแล่นจนถึงที่หมายได้ ในปีเดียวกันเอ็ดเวิร์ด สมิธ ได้ให้สัมภาษณ์ว่าเขาไม่สามารถ "จินตนาการถึงเงื่อนไขใดๆที่จะทำให้เรืออับปาง การต่อเรือในสมัยนี้นั้นดีกว่าอดีตมาก"[27]

"ภูเขาน้ำแข็งด้านขวาข้างหน้า!"

ไททานิกเข้าสู่ตรอกภูเขาน้ำแข็ง

ก่อน ไททานิก จะชนเข้ากับภูเขาน้ำแข็ง ผู้โดยสารส่วนใหญ่เข้านอนแล้ว และผู้บังคัญบัญชาในสะพานเดินเรือได้เปลี่ยนกะจากต้นเรือที่สอง ชาร์ล ไลทิลเลอร์ (Charles Lightoller) เป็นต้นเรือที่หนึ่ง วิลเลียม เมอร์ด็อก (William Murdoch) พนักงานเฝ้าระวัง เฟรดเดอริก ฟลีท (Frederick Fleet) และเรจินัลด์ ลี (Reginald Lee) ประจำในรังกาสูง 29 เมตร (95 ฟุต) เหนือดาดฟ้าเรือ อุณหภูมิอากาศลดลงจนใกล้ถึงจุดเยือกแข็ง และทะเลก็สงบอย่างสมบูรณ์ พันเอกอาร์ชิบัลด์ เกรซี่ (Archibald Gracie) หนึ่งในผู้รอดชีวิต เขียนบรรยายไว้ว่า "ทะเลเรียบเหมือนแก้วจนสะท้อนภาพดวงดาวออกมาได้อย่างชัดเจน"[28] ซึ่งเป็นที่ทราบกันดีว่าทะเลที่สงบเป็นพิเศษนี้เป็นสัญญาณว่ามีก้อนน้ำแข็งในบริเวณใกล้เคียง[29]

แม้ว่าอากาศจะแจ่มใส แต่เนื่องด้วยจันทร์ดับและทะเลก็สงบ ทำให้ระบุตำแหน่งของภูเขาน้ำแข็งในบริเวณใกล้เคียงได้ยาก เพราะหากทะเลมีคลื่นแรง คลื่นที่ปะทะกับภูเขาน้ำแข็งจะทำให้พวกมันมองเห็นได้ง่ายขึ้น[30] อีกทั้ง ด้วยสถานการณ์สับสนวุ่นวายที่เซาแทมป์ตัน พนักงานเฝ้าระวังจึงไม่มีกล้องส่องทางไกล แต่ก็มีรายงานว่ากล้องส่องทางไกลจะไร้ประสิทธิภาพในความมืดที่มีเพียงแสงดาวและแสงจากตัวเรือเอง[31] แต่กระนั้นก็ดี พนักงานเฝ้าระวังยังคงเฝ้าระวังอันตรายจากน้ำแข็งตามคำสั่งของไลทิลเลอร์ที่สั่งให้พนักงานเฝ้าระวังและลูกเรือคนอื่นๆ "มองออกไป ระวังน้ำแข็ง โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งก้อนน้ำแข็งขนาดเล็กและชิ้นน้ำแข็ง"[d][32]

เมื่อเวลา 23:30 น. ฟลีทและลีสังเกตเห็นหมอกเล็กน้อยที่เส้นขอบฟ้าเบื้องหน้า แต่ก็ไม่ได้ตอบสนองกับเหตุการณ์นี้ ผู้เชี่ยวชาญบางคนเชื่อว่าหมอกนี้เป็นภาพลวงตาที่เกิดจากน้ำเย็นพบกับอากาศร้อน - คล้ายกับภาพลวงตาของน้ำในทะเลทราย - เมื่อ ไททานิก เข้ามาในตรอกภูเขาน้ำแข็ง (Iceberg Alley) หมอกนี้ส่งผลให้เกิดเส้นขอบฟ้าที่สูงขึ้น ทำให้พนักงานเฝ้าระวังมองไม่เห็นสิ่งที่อยู่ไกลออกไป[33][34]

ชน

เก้านาทีต่อมา เมื่อเวลา 23:39 น. ฟลีทจับภาพภูเขาน้ำแข็งในเส้นทางของ ไททานิก ได้ เขาสั่นระฆังเตือนสามครั้งและโทรศัพท์ถึงสะพานเดินเรือแจ้งแก่ต้นเรือที่หก เจมส์ มู้ดดี้ (James Moody) ฟลีทถาม "มีใครอยู่บ้างไหม?" มู้ดดี้ "มี คุณเห็นอะไร?" ฟลีทตอบ "ภูเขาน้ำแข็งด้านขวาข้างหน้า!"[35] หลังจากขอบคุณฟรีท มู้ดดี้ส่งข้อความถึงเมอร์ด็อก เมอร์ด็อกสั่งนายกราบ โรเบิร์ต ฮิเชนส์ (Robert Hichens) ให้เปลี่ยนเส้นทางเดินเรือ[36] เชื่อกันว่าเมอร์ด็อกได้สั่ง "หักขวาเต็มตัว" ซึ่งจะส่งผลให้พังงาเรือหมุนไปทางขวาจนสุด เพื่อพยายามที่จะทำให้เรือเลี้ยวไปทางซ้าย[31] ซึ่งเป็นเรื่องปกติในเรืออังกฤษยุคนั้น แต่จะกลับทิศทางกันเมื่อเทียบกับการเลี้ยวเรือในปัจจุบัน และเขาเขายังสั่ง "ถอยหลังเต็มที่" บนเครื่องสั่งจักร[22]

อ้างอิงจากต้นเรือที่สี่ โจเซฟ บ็อกซ์ฮอล (Joseph Boxhall) เมอร์ด็อกบอกกัปตันสมิธว่าเขากำลังพยายามที่จะ"หักหลบภูเขาน้ำแข็ง" โดยเขาพยายามแกว่งหัวเรือไปใกล้สิ่งกีดขวาง และแกว่งท้ายเรือเพื่อให้ปลายทั้งสองด้านของเรือหลีกเลี่ยงการชน แต่เกิดความล่าช้าในการกระทำตามคำสั่งทั้งสอง เนื่องด้วยกลไกการคัดท้ายด้วยไอน้ำใช้เวลา 30 วินาทีในการเปลี่ยนหางเสือเรือ[22] และความซับซ้อนในการตั้งค่าเครื่องยนต์ให้ถอยกลับต้องใช้เวลาพอสมควร[37] เนื่องจากกังหันตำแหน่งกลางไม่สามารถย้อนกลับได้ และทั้งกังหันและใบจักรมีตำแหน่งอยู่ด้านหน้าหางเสือเรือ ทำให้เมื่อหยุดใบจักรศักยภาพของหางเสือจะลดลง ดังนั้นจึงทำให้ความสามารถในการเลี้ยวของเรือลดลง หากเมอร์ด็อกเลี้ยวเรือขณะที่ยังรักษาความเร็วไว้ ไททานิก อาจหลบภูเขาน้ำแข็งได้ระยะห่างถึง 1 ฟุต[38]

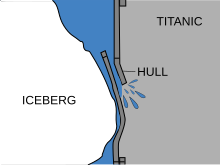

ในสถานการณ์ การหักเลี้ยวของ ไททานิก ทำให้หลีกเลี่ยงไม่ให้หัวเรือชนกับก้อนน้ำแข็งได้ แต่ก็ทำให้เรือกระแทกกับภูเขาน้ำแข็งด้วยการแฉลบไป เดือยน้ำแข็งใต้น้ำขูดยาวไปทางด้านกราบขวาของเรือประมาณเจ็ดวินาที มีก้อนน้ำแข็งที่แตกออกจากส่วนบนของภูเขาน้ำแข็งตกลงบนดาดฟ้าเรือด้านหน้า[39] ประมาณห้านาทีหลังการชน เครื่องยนต์ทุกเครื่องของ ไททานิก ก็ดับลง หัวเรือที่หัวไปทิศเหนือได้บ่ายหัวอย่างช้าๆไปทิศใต้ในกระแสน้ำแลบราดอร์[40]

ผลของการชน

ผลของการชนกับภูเขาน้ำแข็งทำให้เกิดช่องเปิดขนาดใหญ่ที่ตัวเรือ ไททานิก "มีความยาวไม่น้อยกว่า 300 ฟุต (91 เมตร) สูง 10 ฟุต (3 เมตร) จากระดับกระดูกงู"[41] ในการไต่สวนของอังกฤษหลังจากเกิดอุบัติเหตุ เอ็ดเวิร์ด ไวล์ดิ้ง (Edward Wilding) (หัวหน้าวิศวกรรมต่อเรือแห่งฮาร์แลนด์และวูล์ฟ) คำนวณบนพื้นฐานจากการสังเกตการณ์จากน้ำท่วมที่เกิดขึ้นในห้องเรือด้านหน้าที่เกิดขึ้นภายในสี่สิบนาทีหลังจากการชน ยืนยันว่าพื้นที่ช่องเปิดรั่วของเรือ "ประมาณ 12 ตารางฟุต (1.1 ตารางเมตร)"[42] นอกจากนี้เขายังระบุด้วยว่า "ฉันเชื่อว่าช่องเปิดต้องไม่ยาวต่อเนื่อง" แต่เป็นช่องเปิดหลายช่อง ยาวออกไปประมาณ 300 ฟุต ซึ่งเป็นเหตุผลของน้ำท่วมในหลายๆห้องเรือ[42] จากการสำรวจซากเรือด้วยคลื่นเสียงความถี่สูงสมัยใหม่ พบว่าความเสียหายที่แท้จริงบนตัวเรือนั้น คล้ายกับรายงานของไวล์ดิ้ง ซึ่งประกอบด้วยช่องเปิดแคบที่เกิดจากการชนหกช่อง คิดเป็นพื้นที่ทั้งหมดประมาณ 12 ถึง 13 ตารางฟุต (1.1 ถึง 1.2 ตารางเมตร) อ้างอิงกับ พอล เค. แมทเธียสส์ (Paul K. Matthias) ที่ทำการวัดความเสียหาย ความเสียหายประกอบด้วย "มีลำดับของความผิดรูปในด้านกราบขวาที่ไม่ต่อเนื่องยาวตามตัวเรือ ... ประมาณ 10 ฟุต (3 เมตร) เหนือท้องเรือ"[43]

ช่องเปิดที่ยาวที่สุดซึ่งยาวประมาณ 39 ฟุต (12 เมตร) ปรากฏยาวไปตามเส้นแผ่นตัวเรือ นี่แสดงให้เห็นว่าหมุดเหล็กตามแนวตะเข็บของแผ่นหลุดออกทำให้เกิดช่องว่างแคบๆที่น้ำเข้าตัวเรือได้ วิศวกรจากฮาร์แลนด์และวูล์ฟ (Harland and Wolff) ผู้สร้าง ไททานิก ได้เสนอสถานการณ์ที่น่าจะเป็นนี้ในการไต่สวนของกรรมาธิการเหตุอับปางแห่งสหราชอาณาจักรหลังจากเกิดภัยพิบัติ แต่มุมมองของเขาไม่มีใครเชื่อถือ[43] โรเบิร์ต บาลลาร์ด ผู้ค้นพบซากเรือ ไททานิก ได้ให้ความเห็นว่าเรือที่ประสบเหตุเนื่องจากรอยแตกนั้น "เป็นผลพลอยได้จากมนต์ขลังของไททานิก ไม่มีใครเชื่อว่าเรือใหญ่ลำนี้จะอับปางด้วยเสี้ยนไม้"[44] ความผิดพลาดในตัวเรืออาจเป็นปัจจัยร่วม ชิ้นส่วนของแผ่นเหล็กที่กู้คืนมาดูเหมือนจะแตกหักเป็นชิ้นเมื่อกระทบกับภูเขาน้ำแข็งโดยไม่โค้งงอ[45]

แผ่นเหล็กในส่วนกลาง 60 เปอร์เซ็นต์ของตัวเรือถูกยึดด้วยหมุดเหล็กเหนียวสามแถว แต่แผ่นเหล็กที่หัวเรือและท้ายเรือถูกยึดติดด้วยหมุดเหล็กอ่อนสองแถว ซึ่งตามความเห็นของนักวิทยาศาสตร์ด้านวัสดุทิม โฟค (Tim Foecke) และเจนนิเฟอร์ แมคคาร์ตี้ (Jennifer McCarty) - หมุดเข้าใกล้กับขีดจำกัดความเค้นก่อนเกิดการชน[46][47] "Best" หรือหมุดเหล็ก No. 3 มีกากแร่ในระดับสูงทำให้มีความเปราะมากกว่า "Best-Best" หรือหมุดเหล็ก No. 4 และมีแนวโน้มที่จะแตกหักเมื่อเกิดความเค้น โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในช่วงที่อากาศเย็นจัด[48][49] ทอม แมคคลัสกี้ (Tom McCluskie) นักจดหมายเหตุเกษียณอายุของฮาร์แลนด์และวูล์ฟ ชี้ให้เห็นว่าเรือ โอลิมปิก ซึ่งเป็นเรือพี่น้องกับ ไททานิก ใช้หมุดเหล็กชนิดเดียวกัน และให้บริการโดยไม่เกิดอุบัติเหตุเป็นเวลาเกือบ 25 ปี รอดพ้นจากการชนหนักหลายครั้ง ซึ่งรวมถึงการถูกกระแทกโดยเรือลาดตระเวนอังกฤษ[50] เมื่อ โอลิมปิก ชนและจมเรืออู อู 103 ทางหัวเรือ ทวนหัวบิด แผ่นเหล็กตัวเรือทางกราบขวาโค้งงอ แต่ไม่ทำลายความมั่นคงของตัวเรือ[50][51]

เหนือเส้นน้ำลึกมีหลักฐานของการชนกันเพียงเล็กน้อย บริกรในห้องรับประทานอาหารชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาสสังเกตเห็นความสั่นสะเทือน ซึ่งพวกเขาคิดว่าอาจเกิดจากปลดใบจักร ผู้โดยสารหลายคนรู้สึกว่าถูกกระแทกหรือรู้ถึงความสั่นสะเทือน - "ราวกับว่าหินหลายพันก้อนถล่มลงมา"[52] ตามที่ผู้รอดชีวิตคนหนึ่งกล่าวเอาไว้ แต่พวกเขาก็ไม่รู้ว่าเกิดอะไรขึ้น[53] ผู้ที่อยู่บนดาดฟ้าเรือชั้นล่างสุดซึ่งใกล้กับจุดที่เกิดการปะทะมากที่สุด จะรู้สึกคล้ายกันแต่รุนแรงกว่า พนักงานหล่อลื่นเครื่องยนต์ วอลเตอร์ เฮิร์สต์ (Walter Hurst) จำได้ว่า "ตื่นขึ้นจากการชนบดยาวไปทางกราบขวา ไม่มีใครตื่นตกใจมาก แต่รู้ว่าเราชนอะไรบางอย่าง"[54] พนักงานดับเพลิง จอร์จ เคมมิซ (George Kemish) ได้ยิน "เสียงโครมครามและเสียงฉีกขาด" จากตัวเรือด้านกราบขวา[55]

น้ำไหลเข้าท่วมเรือในทันทีด้วยในอัตราเร็วประมาณ 7.1 ตันต่อวินาทีซึ่งเร็วกว่าที่เรือจะสูบออกได้ถึงสิบห้าเท่า[56] รองต้นกล เจ. เอช. เฮชเซ็ธ (J. H. Hesketh) และหัวหน้าผู้ควบคุมเตาไฟ เฟรดเดอริก บาร์เร็ตต์ (Frederick Barrett) ทั้งคู่ถูกกระแทกด้วยน้ำที่เย็นเยือกที่พุ่งเข้ามาจากรอยแยกในห้องหม้อไอน้ำหมายเลข 6 และหนีออกไปได้ก่อนที่ประตูผนึกน้ำจะถูกปิด[57] นี่เป็นสถานการณ์ที่อันตรายอย่างยิ่งสำหรับเจ้าหน้าที่วิศวกรรม หม้อไอน้ำยังคงเต็มไปด้วยไอน้ำร้อนแรงดันสูง และมีความเสี่ยงสูงที่จะเกิดการระเบิดหากสัมผัสกับน้ำทะเลที่เย็นเยือกที่ไหลเข้าท่วมห้องหม้อไอน้ำ ผู้ควบคุมเตาไฟและพนักงานดับเพลิงได้รับคำสั่งให้ลดไฟและระบายหม้อไอน้ำทิ้ง โดยส่งไอน้ำปริมาณมากขึ้นไปในท่อระบาย เมื่อเสร็จงานน้ำได้ท่วมลึกถึงเอวแล้ว[58]

ดาดฟ้าเรือชั้นล่างสุดของ ไททานิก แบ่งเป็น 16 ห้อง แต่ละห้องแบ่งแยกจากกันด้วยผนังกั้นห้องยาวไปตามความกว้างของตัวเรือ มีทั้งสิ้น 15 ผนัง แต่ละผนังกั้นสูงถึงดาดฟ้าเรือชั้น E สูง 11 ฟุต (3.4 เมตร) เหนือเส้นน้ำลึก สองห้องใกล้หัวเรือและหกห้องใกล้ท้ายเรือ ผนังกั้นสูงขึ้นไปถึงดาดฟ้าเรืออีกชั้น - ชั้น D[59]

แต่ละผนังกั้นห้องสามารถปิดผนึกด้วยประตูผนึกน้ำ ห้องเครื่องยนต์และห้องหม้อไอน้ำบนท้องเรือชั้นในมีประตูเป็นแบบแนวดิ่งที่สามารถควบคุมระยะไกลได้จากสะพานเดินเรือ ปิดโดยอัตโนมัติโดยทุ่นลอยถ้าน้ำท่วม หรือปิดโดยลูกเรือเอง ประตูจะใช้เวลาปิดประมาณ 30 วินาที สัญญาณเตือนภัยและทางหลบหนีอื่นได้ถูกจัดเตรียมไว้เพื่อไม่ให้ลูกเรือติดอยู่ในห้อง เหนือท้องเรือชั้นในบนดาดฟ้าเรือชั้นท้องเรือ, ดาดฟ้าเรือชั้น F และ ดาดฟ้าเรือชั้น E เป็นประตูปิดในแนวขวางและปิดด้วยมือ ประตูสามารถปิดที่ตัวประตูเองหรือจากดาดฟ้าเรือด้านบน[59]

แม้ว่าผนังกั้นห้องผนึกน้ำจะอยู่เหนือเส้นน้ำลึก แต่ตัวเรือก็ไม่ได้ปิดผนึกที่ดาดฟ้าเรือด้านบน ถ้ามีน้ำท่วมในหลายห้อง หัวเรือจะจมลึกลงไปในน้ำ และน้ำจะล้นทะลักจากห้องหนึ่งไปอีกห้องหนึ่งที่อยู่ถัดไปตามลำดับ คล้ายกับน้ำที่ล้นไปที่ด้านบนของถาดน้ำแข็งเมื่อเอียงถาด ความเสียหายที่เกิดกับ ไททานิก เกิดที่ห้องหัวเรือ ห้องว่างสามห้องถัดไป และห้องหม้อไอน้ำหมายเลข 6 รวมทั้งสิ้น 5 ห้องเรือ ไททานิก ได้รับการออกแบบให้ยังลอยอยู่ได้โดยมีห้องเรือสองห้องถูกน้ำท่วมและเรือจะไม่ล่มถ้าสี่ห้องแรกแตกรั่ว ด้วยห้าห้องเรือที่น้ำท่วมทำให้น้ำท่วมสูงกว่าผนังกั้นห้องไหลท่วมเรือต่อไป[59][60]

กัปตันสมิธรู้สึกถึงแรงสั่นสะเทือนของการชนจากในห้องเคบินของเขาและมาถึงสะพานเดินเรือทันที เมื่อทราบถึงสถานการณ์เขาเรียกโทมัส แอนดรูวส์ (Thomas Andrews) ผู้สร้างไททานิค ซึ่งเป็นหนึ่งในกลุ่มวิศวกรจากฮาร์แลนด์และวูล์ฟที่เข้าร่วมสังเกตการณ์การเดินทางเที่ยวแรกของเรือ[61] เรือเอียงห้าองศาไปทางกราบขวาและหัวเรือจมลงสององศาในห้านาทีหลังการชน[62] สมิธและแอนดรูว์ลงไปด้านล่างและพบว่าห้องเก็บสัมภาระด้านหน้า ห้องไปรษณีย์ และสนามสควอชถูกน้ำท่วม ในขณะที่ห้องหม้อไอน้ำหมายเลข 6 น้ำท่วมลึก 14 ฟุต (4.3 เมตร) และทะลักเข้าสู่หม้อไอน้ำหมายเลข 5 [62] และลูกเรือกำลังดิ้นรนสูบน้ำออก[63]

ภายใน 45 นาทีหลังการชน น้ำอย่างน้อย 13,700 ตันไหลเข้าสู่เรือ นี่เป็นเรื่องที่มากเกินไปที่อับเฉาเรือและปั๊มน้ำท้องเรือของ ไททานิก จะรับมือไหว ความสามารถในการสูบน้ำของปั๊มรวมกันมีทั้งหมดเพียง 1,700 ตันต่อชั่วโมง[64] แอนดรูว์แจ้งกัปตันว่าห้าห้องแรกถูกน้ำท่วม ดังนั้น ไททานิก ถึงจุดจบแล้ว จากการประเมินของเขา เรือจะสามารถลอยตัวได้ไม่เกินสองชั่วโมง[65]

นับจากเวลาของการชนไปจนถึงช่วงเวลาที่เรือจม น้ำอย่างน้อย 36,000 ตัน ไหลท่วมสู่ ไททานิก ทำให้ระวางขับนํ้าของเรือเพิ่มขึ้นเป็นเกือบสองเท่าจาก 49,100 ตัน เป็นมากกว่า 84,000 ตัน[66] น้ำไม่ได้ท่วมในอัตราคงที่และไม่กระจายไปทั่วทั้งเรืออย่างสม่ำเสมอเนื่องจากโครงสร้างของห้องเรือที่ถูกน้ำท่วม การที่เรือเอียงไปทางกราบขวาเนื่องจากน้ำท่วมไม่สมมาตรที่กราบขวา น้ำได้ไหลเทลงทางเดินที่ด้านล่างของเรือ[67] เมื่อทางเดินถูกน้ำท่วมเต็ม การเอียงกลับมาสมดุล แต่ภายหลังเรือกลับมาเอียงไปทางกราบซ้ายถึงสิบองศาเมื่อเกิดน้ำท่วมที่ไม่สมมาตรในด้านนั้น[68]

มุมลดของ ไททานิก ค่อนข้างเปลี่ยนไปอย่างรวดเร็ว จากศูนย์องศาเป็นประมาณสี่องศาครึ่งในช่วงชั่วโมงแรกหลังจากการชน แต่อัตราที่เรือลดลงช้าเป็นอย่างมากในชั่วโมงที่สอง ลดลงเพียงประมาณห้าองศาเท่านั้น[69] สิ่งนี้ทำให้หลายคนบนเรือมีความหวังว่าเรืออาจลอยอยู่นานพอที่พวกเขาจะได้รับการช่วยเหลือ เมื่อเวลา 1:30 น. อัตราการจมลงของหัวเรือเพิ่มขึ้นจนกระทั่ง ไททานิก มีมุมลดประมาณสิบองศา[68] เมื่อเวลาประมาณ 02:15 น. ไททานิก จมลงในน้ำอย่างรวดเร็วเมื่อน้ำไหลเข้าไปในส่วนที่ไม่มีการท่วมมาก่อนหน้านี้ผ่านทางปากระวางดาดฟ้าเรือ เรือจมหายไปจากสายตาที่เวลา 02:20 น.[70]

15 เมษายน 1912

เตรียมพร้อมสละเรือ

เมื่อเวลา 00:05 น. ของวันที่ 15 เมษายน กัปตันสมิธสั่งให้เปิดใช้เรือชูชีพและรวมพลผู้โดยสาร[60] นอกจากนี้ เขายังสั่งให้พนักงานวิทยุเริ่มส่งข้อความขอความช่วยเหลือ ข้อความดังกล่าวได้ระบุต่ำแหน่งของเรือผิดพลาดโดยระบุว่าอยู่ด้านตะวันตกของแนวน้ำแข็ง ทำให้ผู้ช่วยเหลือเดินทางไปยังตำแหน่งที่ผิดไปประมาณ 13.5 ไมล์ทะเล (15.5 ไมล์; 25.0 กม.) [20][71] ใต้ดาดฟ้าเรือ น้ำได้ไหลลงสู่จุดต่ำสุดของเรือ เช่น ห้องไปรษณีย์ที่ถูกน้ำท่วม ที่ซึ่งพนักงานคัดแยกจดหมายพยายามรักษาไปรษณีย์ 400,000 ชิ้นบน ไททานิก อย่างสุดความสามารถ ในที่อื่นๆ สามารถได้ยินเสียงอากาศที่ถูกน้ำเข้าแทนที่[72] เหนือพื้นที่เหล่านั้น บริกรได้เดินไปตามทางจากประตูสู่ประตู เพื่อปลุกผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือที่นอนหลับและบอกให้พวกเขาขึ้นไปที่ดาดฟ้าเรือ เนื่องจาก ไททานิก ไม่มีระบบเสียงประกาศสาธารณะ[73]

การแจ้งรวมพลขึ้นกับชั้นของผู้โดยสารเป็นอย่างมาก บริกรชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาสรับผิดชอบเพียงสองสามห้องเท่านั้น ขณะที่ผู้รับผิดชอบผู้โดยสารชั้นสองและชั้นสามนั้นต้องจัดการคนจำนวนมาก บริกรชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาสได้เข้าช่วยจัดเก็บกระเป๋าเดินทางและนำขึ้นไปบนดาดฟ้าเรือด้วย แต่บริกรชั้นสองและสามส่วนใหญ่ทำได้เพียงเปิดประตูและบอกผู้โดยสารให้สวมเสื้อชูชีพและขึ้นไปด้านบน ในชั้นสามผู้โดยสารส่วนใหญ่จะถูกทิ้งไว้ทันทีเนื่องด้วยมีผู้คนจำนวนมากที่ต้องจัดการ หลังจากได้รับแจ้งถึงความจำเป็นที่จะต้องขึ้นไปบนดาดฟ้าเรือ[74] ผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือจำนวนมากลังเลที่จะปฏิบัติตาม ปฏิเสธที่จะเชื่อว่าเกิดปัญหาขึ้น หรือขออยู่ในเรือที่อบอุ่นดีกว่าออกไปเผชิญอากาศที่หนาวเหน็บยามค่ำคืน เหล่าผู้โดยสารไม่ได้รับแจ้งเลยว่าเรือกำลังจม แต่มีไม่กี่คนที่สังเกตเห็นว่าเรือเอียง[73]

ราว 00:15 น. บริกรสั่งให้ผู้โดยสารสวมเสื้อชูชีพ[75] ซึ่งผู้โดยสารจำนวนมากมองว่าเป็นเรื่องตลก[73] ผู้โดยสารบางกลุ่มได้ร่วมเล่นฟุตบอลโดยใช้ชิ้นน้ำแข็งที่ตอนนี้ตกเกลื่อนไปทั่วส่วนหน้าของดาดฟ้าเรือต่างลูกฟุตบอล[76] บนดาดฟ้าเรือขณะที่ลูกเรือเริ่มเตรียมเรือชูชีพ เสียงไอน้ำแรงดันสูงที่ระบายออกจากหม้อไอน้ำและปล่อยออกมาทางปล่องเรือด้านบนดังเป็นอย่างมา จนยากที่จะได้ยินเสียงอะไรอื่นอีก ลอว์เรนซ์ บีส์ลีย์ (Lawrence Beesley) บรรยายเสียงนี้ไว้ว่า "เสียงที่ดังกึกก้องและเสียงอึกทึกที่ทำให้การสนทนาเป็นเรื่องยาก ให้จินตนาการว่าหัวรถจักร 20 หัวปล่อยไอน้ำในคีย์เสียงต่ำ นั่นแหละคือเสียงที่ไม่พึงประสงค์ที่เราประสบในขณะที่เราปีนขึ้นไปบนดาดฟ้าเรือ"[77] เสียงนั้นดังมากจนลูกเรือต้องใช้สัญญาณมือเพื่อสื่อสาร[78]

ไททานิก มีเรือชูชีพทั้งสิ้น 20 ลำ ประกอบไปด้วยเรือไม้ 16 ลำบนหลักเดวิท (เสาแขวนเรือ) ข้างลำเรือด้านละ 8 ลำ และเรือชูชีพพับได้ 4 ลำที่พื้นเป็นพื้นไม้และด้านข้างเป็นผ้าใบ[73] ซึ่งเรือชูชีพพับได้ถูกเก็บรักษาในลักษณะที่พับไว้และคว่ำลง ก่อนใช้งานต้องทำการติดตั้งและย้ายไปยังหลักเดวิทเพื่อปล่อยเรือ[79] สองลำถูกเก็บไว้ใต้เรือไม้ อีกสองลำถูกเก็บไว้บนห้องพักของเจ้าหน้าที่[80] ซึ่งสองลำหลังทำการปล่อยเรือได้ยากมากเนื่องจากแต่ละลำมีน้ำหนักหลายตันและต้องใช้แรงงานคนเพื่อนำลงไปที่ดาดฟ้าเรือ[81] โดยเฉลี่ยแล้วเรือชูชีพสามารถรองรับได้ถ 68 คนต่อลำ และเมื่อรวมกันแล้วสามารถรองรับได้ 1,178 คน เกือบครึ่งหนึ่งของจำนวนคนบนเรือ หรือหนึ่งในสามของจำนวนผู้โดยสารสูงสุดที่เรือได้รับอนุญาต ปัญหาการขาดแคลนเรือชูชีพไม่ได้เกิดจากการไม่มีพื้นที่หรือเพราะค่าใช้จ่าย ไททานิก ได้รับการออกแบบให้สามารถรองรับเรือชูชีพได้ถึง 68 ลำ[82] ซึ่งเพียงพอสำหรับทุกคนบนเรือและราคาของเรือชูชีพ 32 ลำ มีราคาอยู่ที่ 16,000 ดอลลาร์สหรัฐเท่านั้น (เทียบเท่ากับ 424,000 ดอลลาร์ในปี 2019)[83] ซึ่งคิดเป็นเศษของเงิน 7.5 ล้านดอลลาร์ที่บริษัทใช้ไปกับ ไททานิก เท่านั้น

ในเวลานั้น เรือชูชีพมีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อใช้ในการเคลื่อนย้ายผู้โดยสารจากเรือที่ประสบปัญหาไปยังเรือที่อยู่ใกล้เคียงเมื่อเกิดกรณีฉุกเฉิน[84][f] ดังนั้นจึงเป็นเรื่องธรรมดาที่เรือเดินสมุทรจะมีเรือชูชีพน้อยกว่าจำนวนผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือทั้งหมด จากเรือเดินสมุทรอังกฤษ 39 ลำที่มีความยาวมากกว่า 10,000 ตัน มีถึง 33 ลำที่มีเรือชูชีพน้อยเกินไปที่จะรองรับทุกคนบนเรือ[86] ไวต์สตาร์ไลน์ต้องการให้เรือมีดาดฟ้าพักผ่อนที่กว้างพร้อมมองเห็นวิวทิวทัศน์ของทะเลโดยไม่มีแถวเรือชูชีพมาบดบัง[87]

กัปตันสมิธเป็นนักเดินเรือที่มีประสบการณ์ ได้ปฏิบัติหน้าที่เป็นเวลาถึง 40 ปีในทะเลซึ่งรวมถึง 27 ปีในการเป็นผู้บังคับบัญชาด้วย เหตุการณ์นี้เป็นวิกฤตครั้งแรกในอาชีพของเขาและเขารู้ดีว่าแม้ว่าจะบรรทุกคนเต็มลำเรือชูชีพทั้งหมด แต่ก็จะมีคนมากกว่าหนึ่งพันคนที่ยังคงเหลืออยู่บนเรือขณะที่เรือจมลง ซึ่งคนเหล่านี้มีโอกาสรอดเพียงเล็กน้อยหรืออาจไม่มีเลย[60] บางแหล่งข้อมูลอ้างว่า เมื่อกัปตันสมิธตระหนักถึงความร้ายแรงของเหตุกรณ์ที่เกิดขึ้น สมิธถึงกับตัวแข็งตะลึงงัน และไม่ได้เข้าช่วยเหลือในการป้องกันการสูญเสียชีวิต[88][89] แต่ตามแหล่งข้อมูลอื่น กัปตันสมิธมีความรับผิดชอบและดำเนินการอย่างเต็มที่ในช่วงวิกฤต หลังจากการชน กัปตันสมิธได้เริ่มการตรวจสอบความเสียหายทันที โดยทำการตรวจสอบถึงสองครั้งด้านล่างดาดฟ้าเรือเพื่อค้นหาความเสียหาย และให้พนักงานวิทยุเตรียมพร้อมสำหรับความเป็นไปได้ที่จะต้องขอความช่วยเหลือ เขาสั่งให้ลูกเรือของเขาเริ่มเตรียมเรือชูชีพสำหรับการอพยพและให้ผู้โดยสารสวนชูชีพก่อนที่เขาจะได้รับแจ้งจากแอนดรูวส์ว่าเรือกำลังจะจมเสียอีก กัปตันสมิธเข้าสังเกตการรอบ ๆ ดาดฟ้าเรือ ตรวจตราดูแลและช่วยเหลือผู้โดยสารลงเรือชูชีพ ปฏิสัมพันธ์กับผู้โดยสาร และสร้างความสมดุลระหว่างความเร่งด่วนในการอพยพและพยายามห้ามปรามความตื่นตระหนก[90]

การออกเดินทางของเรือชูชีพ

เรือชูชีพลำสุดท้าย

นาทีสุดท้ายก่อนอับปาง

วาระสุดท้ายของ ไททานิก

ผู้โดยสารและลูกเรือในน้ำ

การช่วยชีวิตและการออกเดินทาง

ผู้รอดชีวิตของเรือ ไททานิก ได้รับการช่วยเหลือในเวลาประมาณ 04:00 น. วันที่ 15 เมษายนโดยอาร์เอ็มเอส คาร์เพเทีย ที่แล่นด้วยความเร็วเต็มที่มาตลอดคืนบนเส้นทางเสี่ยงอันตราย ซึ่งเรือต้องเลี้ยวหลบภูเขาน้ำแข็งหลายลูกตลอดเส้นทางมายังจุดอับปาง[91] แสงไฟจาก คาร์เพเทีย ถูกพบครั้งแรกราวเวลา 03:30 น.[91] ซึ่งสร้างกำลังใจให้ผู้รอดชีวิตเป็นอย่างมาก แม้ว่าจะต้องใช้เวลาอีกหลายชั่วโมงกว่าที่ทุกคนจะถูกพาขึ้นเรือ

การบาดเจ็บล้มตายและผู้รอดชีวิต

จำนวนผู้เสียชีวิตจากการอับปางยังไม่ชัดเจนเนื่องจากปัจจัยหลายประการ ที่เกิดจากความสับสนเกี่ยวกับรายชื่อผู้โดยสาร จากรายชื่อของผู้ที่ยกเลิกการเดินทางในนาทีสุดท้าย และการที่มีผู้โดยสารหลายรายเดินทางด้วยนามแฝงด้วยเหตุผลหลายประการ ซึ่งอาจถูกนับรายชื่อสองครั้งในรายชื่อผู้เสียชีวิต[92] มีผู้เสียชีวิตในเหตุการณ์ประมาณ 1,490 ถึง 1,635 คน[93] ตัวเลขมาจากรายงานภัยพิบัติของกระทรวงพาณิชย์อังกฤษ[94]

| ผู้โดยสาร | ประเภท | จำนวนผู้โดยสาร | อัตราร้อยละเทียบกับทั้งหมด | จำนวนผู้รอดชีวิต | จำนวนเสียชีวิต | อัตราร้อยละผู้รอดชีวิต | อัตราร้อยละเสียชีวิต | อัตราร้อยละผู้รอดชีวิตเทียบกับทั้งหมด | อัตราร้อยละผู้เสียชีวิตเทียบกับทั้งหมด |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| เด็ก | เฟิร์สต์คลาส | 6 | 0.3% | 5 | 1 | 83% | 17% | 0.2% | 0.04% |

| ชั้นสอง | 24 | 1.1% | 24 | 0 | 100% | 0% | 1.1% | 0% | |

| ชั้นสาม | 79 | 3.6% | 27 | 52 | 34% | 66% | 1.2% | 2.4% | |

| รวม | 109 | 5% | 56 | 53 | 51% | 49% | 2.5% | 2.4% | |

| ผู้หญิง | เฟิร์สต์คลาส | 144 | 6.5% | 140 | 4 | 97% | 3% | 6.3% | 0.2% |

| ชั้นสอง | 93 | 4.2% | 80 | 13 | 86% | 14% | 3.6% | 0.6% | |

| ชั้นสาม | 165 | 7.4% | 76 | 89 | 46% | 54% | 3.4% | 4.0% | |

| ลูกเรือ | 23 | 1.0% | 20 | 3 | 87% | 13% | 0.9% | 0.1% | |

| รวม | 425 | 19.1% | 316 | 109 | 74% | 26% | 14.2% | 4.9% | |

| ผู้ชาย | เฟิร์สต์คลาส | 175 | 7.9% | 57 | 118 | 33% | 67% | 2.6% | 5.3% |

| ชั้นสอง | 168 | 7.6% | 14 | 154 | 8% | 92% | 0.6% | 6.9% | |

| ชั้นสาม | 462 | 20.8% | 75 | 387 | 16% | 84% | 3.3% | 17.4% | |

| ลูกเรือ | 885 | 39.8% | 192 | 693 | 22% | 78% | 8.6% | 31.2% | |

| รวม | 1,690 | 75.9% | 338 | 1,352 | 20% | 80% | 15.2% | 60.8% | |

| รวม | All | 2,224 | 100% | 710 | 1,514 | 32% | 68% | 31.9% | 68.1% |

มีผู้รอดชีวิตจากภัยพิบัติน้อยกว่าหนึ่งในสามของจำนวนคนบนเรือ ไททานิก ผู้รอดชีวิตบางคนเสียชีวิตหลังจากนั้นไม่นานจากการบาดเจ็บและการติดเชื้อ ทำให้มีผู้ที่ได้รับการช่วยเหลือจากเรือ คาร์เพเทีย หลายคนเสียชีวิต[95] จากตารางมีผู้เสียชีวิตเป็นเด็ก 49 % ผู้หญิง 26 % ผู้ชาย 82 % และลูกเรือ 78 % อีกทั้ง ตัวเลขดังกล่าวยังแสดงให้เห็นถึงความแตกต่างอย่างสิ้นเชิงในอัตราการรอดชีวิตระหว่างผู้ชายและผู้หญิง และผู้โดยสารชั้นต่างๆบนเรือ ไททานิก โดยเฉพาะในกลุ่มผู้หญิงและเด็ก แม้ว่าผู้หญิงชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาสและชั้นสอง (รวมกัน) เสียชีวิตไม่ถึง 10 % แต่ผู้หญิงในชั้นสามเสียชีวิตถึง 54 % ในทำนองเดียวกัน เด็กชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาสห้าในหกคนและเด็กชั้นสองทั้งหมดรอดชีวิต แต่เด็กในชั้นสาม 52 ใน 79 คนเสียชีวิต[96] เด็กชั้นเฟิร์สต์คลาสที่เสียชีวิตคือ ลอเรน แอลลิสัน (Loraine Allison) อายุ 2 ปี[97] ทั้งนี้ การสูญเสียที่หนักที่สุดคือผู้โดยสารชายชั้นสอง มีจำนวนผู้เสียชีวิตถึง 92 % นอกจากนี้ ยังมีสัตว์เลี้ยงสามตัวรอดชีวิตจากการอับปาง[98]

ผลที่ตามมา

เชิงอรรถ

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 ในช่วงเวลาของการชน นาฬิกาของ ไททานิก ถูกตั้งไว้ล่วงหน้า 2 ชั่วโมง 2 นาทีจากเขตเวลาตะวันออก และ 2 ชั่วโมง 58 นาทีหลังเวลามาตรฐานกรีนิช เวลาเดินเรือถูกตั้งเวลา ณ เที่ยงคืน 13–14 เมษายน 1912 และขึ้นกับการคาดการณ์ตำแหน่งของ ไททานิก ณ เที่ยงวันของวันที่ 14 เมษายน ซึ่งจะขึ้นอยู่กับการสังเกตดวงดาวในตอนค่ำของวันที่ 13 เมษายน ซึ่งจะปรับโดยการนำร่องโดยใช้การคำนวณ (dead reckoning) แต่เนื่องจากภัยพิบัติที่เกิดขึ้น นาฬิกาของไททานิกจึงไม่ได้ปรับเวลา ณ เที่ยงคืนของวันที่ 14-15 เมษายน[1]

- ↑ เรือลำที่สามคือ อาร์เอ็มเอส บริแทนนิก ซึ่งไม่เคยประจำการเป็นเรือโดยสาร แต่ประจำการเป็นเรือพยาบาล เอชเอ็มเอชเอส บริแทนนิก (ระหว่างสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 1)

- ↑ วิทยุโทรเลขหรือที่รู้จักกันในชื่อโทรเลขไร้สายในยุคนั้น

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 growler: "ภูเขาน้ำแข็งขนาดเล็กหรือแพน้ำแข็งที่เกือบมองไม่เห็นบนผิวน้ำ"

- ↑ ถึงแม้ว่าภายหลังจะความเชื่ออย่างเช่นใน ภาพยนตร์ไททานิกปี 1997 ว่า ไททานิก ไม่ได้พยายามสร้างสถิติความเร็วในการข้ามมหาสมุทรแอตแลนติก ไวต์สตาร์ไลน์นั้นตัดสินใจที่จะไม่แข่งขันกับคู่แข่งอย่างคูนาร์ดไลน์ด้วยความเร็ว แต่จะมุ่งเน้นแข่งขันด้วยขนาดและความหรูหราแทน[25]

- ↑ เหตุการณ์ที่ยืนยันหลักการนี้ในขณะที่ ไททานิก อยู่ระหว่างการก่อสร้างคือ เรือ อาร์เอ็มเอส รีพับบลิก ของไวต์สตาร์ไลน์เกิดอุบัติเหตุชนกันและอับปางลง แม้ว่าเรือจะมีเรือชูชีพไม่เพียงพอสำหรับผู้โดยสารทุกคน แต่ผู้โดยสารก็รอดชีวิตทั้งหมด เพราะเรือสามารถลอยอยู่ได้นานพอที่จะย้ายผู้โดยสารทั้งหมดไปยังเรือที่มาช่วยเหลือ[85]

อ้างอิง

- ↑ Halpern 2011, p. 78.

- ↑ Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 37.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Butler 1998, p. 10.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Butler 1998, pp. 16–20.

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 67.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 71.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 76.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 77.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Butler 1998, p. 238.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 83.

- ↑ Butler 1998, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Howells 1999, p. 95.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 49.

- ↑ Fire Down Below – by Samuel Halpern. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ↑ Halpern & Weeks 2011, pp. 122–26.

- ↑ Halpern 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Ryan 1985, p. 8.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ballard 1987, p. 199.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Ryan 1985, p. 9.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Barczewski 2006, p. 191.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Ryan 1985, p. 10.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Ryan 1985, p. 11.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 24.

- ↑ Mowbray 1912, p. 278.

- ↑ Barczewski 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ Gracie 1913, p. 247.

- ↑ Halpern 2011, p. 85.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1987, p. 19.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Brown 2000, p. 47.

- ↑ Barratt 2010, p. 122.

- ↑ Broad, William J. (9 เมษายน 2012). "A New Look at Nature's Role in the Titanic's Sinking". The New York Times. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 เมษายน 2018.

- ↑ Lord 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 137.

- ↑ Brown 2000, p. 67.

- ↑ Barczewski 2006, p. 194.

- ↑ Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 100.

- ↑ Halpern 2011, p. 94.

- ↑ Hoffman & Grimm 1982, p. 20.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Testimony of Edward Wilding". สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 ตุลาคม 2014.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Broad 1997.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 25.

- ↑ Zumdahl & Zumdahl 2008, p. 457.

- ↑ Materials Today, 2008.

- ↑ McCarty & Foecke 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Broad 2008.

- ↑ Verhoeven 2007, p. 49.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Ewers 2008.

- ↑ Mills 1993, p. 46.

- ↑ "Testimony of Mrs J Stuart White at the US Inquiry". สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 พฤษภาคม 2017.

- ↑ Butler 1998, pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Barratt 2010, p. 151.

- ↑ Barratt 2010, p. 156.

- ↑ Aldridge 2008, p. 86.

- ↑ Ballard 1987, p. 71.

- ↑ Barczewski 2006, p. 18.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Mersey 1912.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Ballard 1987, p. 22.

- ↑ Barczewski 2006, p. 147.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Butler 1998, p. 71.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 72.

- ↑ Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 112.

- ↑ Barczewski 2006, p. 148.

- ↑ Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 106.

- ↑ Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 118.

- ↑ Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 109.

- ↑ Barratt 2010, p. 131.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 120.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 Barczewski 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 121.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 126.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ Beesley 1960, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 124.

- ↑ Lord 1987, p. 90.

- ↑ Barczewski 2006, p. 21.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 123.

- ↑ Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 112.

- ↑ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 มกราคม 2020.

- ↑ Hutchings & de Kerbrech 2011, p. 116.

- ↑ Chirnside 2004, p. 29.

- ↑ Bartlett 2011, p. 30.

- ↑ Marshall 1912, p. 141.

- ↑ Butler 1998, pp. 250–252.

- ↑ Cox 1999, pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Fitch, Layton & Wormstedt 2012, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Bartlett 2011, p. 238.

- ↑ Butler 1998, p. 239.

- ↑ Lord 1976, p. 197.

- ↑ Mersey 1912, pp. 110–11.

- ↑ Eaton & Haas 1994, p. 179.

- ↑ Howells 1999, p. 94.

- ↑ Copping, Jasper (19 มกราคม 2014). "Lost child of the Titanic and the fraud that haunted her family". The Telegraph. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 16 มิถุนายน 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 มกราคม 2014.

- ↑ Georgiou 2000, p. 18.

บรรณานุกรม

หนังสือ

- Aldridge, Rebecca (2008). The Sinking of the Titanic. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7910-9643-7.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Ballard, Robert D. (1987). The Discovery of the Titanic. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-51385-2.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Barczewski, Stephanie (2006). Titanic: A Night Remembered. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85285-500-0.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Barratt, Nick (2010). Lost Voices From the Titanic: The Definitive Oral History. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-84809-151-1.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Bartlett, W.B. (2011). Titanic: 9 Hours to Hell, the Survivors' Story. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-0482-4.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Beesley, Lawrence (1960) [1912]. "The Loss of the SS. Titanic; its Story and its Lessons". The Story of the Titanic as told by its Survivors. London: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-20610-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Björkfors, Peter (2004). "The Titanic Disaster and Images of National Identity in Scandinavian Literature". ใน Bergfelder, Tim; Street, Sarah (บ.ก.). The Titanic in myth and memory: representations in visual and literary culture. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-431-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Brown, David G. (2000). The Last Log of the Titanic. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-136447-8.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Butler, Daniel Allen (1998). Unsinkable: The Full Story of RMS Titanic. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1814-1.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic-class ships : Olympic, Titanic, Britannic. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2868-0.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Cox, Stephen (1999). The Titanic Story: Hard Choices, Dangerous Decisions. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8126-9396-6.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Eaton, John P.; Haas, Charles A. (1987). Titanic: Destination Disaster: The Legends and the Reality. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 978-0-85059-868-1.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Eaton, John P.; Haas, Charles A. (1994). Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire: Patrick Stephens. ISBN 978-1-85260-493-6.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Everett, Marshall (1912). Wreck and Sinking of the Titanic. Chicago: Homewood Press. OCLC 558974511.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Fitch, Tad; Layton, J. Kent; Wormstedt, Bill (2012). On A Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of the R.M.S. Titanic. Amberley Books. ISBN 1848689276.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Foster, John Wilson (1997). The Titanic Complex. Vancouver: Belcouver Press. ISBN 978-0-9699464-1-0.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Georgiou, Ioannis (2000). "The Animals on board the Titanic". Atlantic Daily Bulletin. Southampton: British Titanic Society. ISSN 0965-6391.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (ลิงก์) - Gittins, Dave; Akers-Jordan, Cathy; Behe, George (2011). "Too Few Boats, Too Many Hindrances". ใน Halpern, Samuel (บ.ก.). Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6210-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Gleicher, David (2006). The Rescue of the Third Class on the Titanic: A Revisionist History. Research in Maritime History, No. 31. St. John's, Newfoundland: International Maritime Economic History Association. ISBN 978-0-9738934-1-0.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Gracie, Archibald (1913). The Truth about the Titanic. New York: M. Kennerley.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help)- Also published as: Gracie, Archibald (2009). Titanic: A Survivor's Story. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-4702-2.

- Halpern, Samuel (2011). "Account of the Ship's Journey Across the Atlantic". ใน Halpern, Samuel (บ.ก.). Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6210-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Halpern, Samuel; Weeks, Charles (2011). "Description of the Damage to the Ship". ใน Halpern, Samuel (บ.ก.). Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6210-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Hoffman, William; Grimm, Jack (1982). Beyond Reach: The Search For The Titanic. New York: Beaufort Books. ISBN 978-0-8253-0105-6.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Howells, Richard Parton (1999). The Myth of the Titanic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-22148-5.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Hutchings, David F.; de Kerbrech, Richard P. (2011). RMS Titanic 1909–12 (Olympic Class): Owners' Workshop Manual. Sparkford, Somerset: Haynes. ISBN 978-1-84425-662-4.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Kuntz, Tom (1998). The Titanic Disaster Hearings. New York: Pocket Book. ISBN 978-1-56865-748-6.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Lord, Walter (1976). A Night to Remember. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-004757-8.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Lord, Walter (2005) [1955]. A Night to Remember. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-8050-7764-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Lord, Walter (1987). The Night Lives On. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-81452-7.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Lynch, Donald (1998). Titanic: An Illustrated History. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-786-86401-0.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Marcus, Geoffrey (1969). The Maiden Voyage. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-45099-2.

- Marshall, Logan (1912). Sinking of the Titanic and Great Sea Disasters. Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Co. OCLC 1328882.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - McCarty, Jennifer Hooper; Foecke, Tim (2012) [2008]. What Really Sank The Titanic – New Forensic Evidence. New York: Citadel. ISBN 978-0-8065-2895-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Mills, Simon (1993). RMS Olympic – The Old Reliable. Dorset: Waterfront Publications. ISBN 0-946184-79-8.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Mowbray, Jay Henry (1912). Sinking of the Titanic. Harrisburg, PA: The Minter Company. OCLC 9176732.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Parisi, Paula (1998). Titanic and the Making of James Cameron. New York: Newmarket Press. ISBN 978-1-55704-364-1.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Regal, Brian (2005). Radio: The Life Story of a Technology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33167-1.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Richards, Jeffrey (2001). Imperialism and Music: Britain, 1876–1953. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6143-1.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Turner, Steve (2011). The Band that Played On. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-59555-219-8.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Verhoeven, John D. (2007). Steel Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist. Materials Park, OH: ASM International. ISBN 978-0-87170-858-8.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Winocour, Jack, บ.ก. (1960). The Story of the Titanic as told by its Survivors. London: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-20610-3.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help) - Zumdahl, Steven S.; Zumdahl, Susan A. (2008). Chemistry. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-547-12532-9.

{{cite book}}:|ref=harvไม่ถูกต้อง (help)

บทความวารสาร

- Foecke, Tim (26 กันยายน 2008). "What really sank the Titanic?". Materials Today. Elsevier. 11 (10): 48. doi:10.1016/s1369-7021(08)70224-4. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 มีนาคม 2012.

- Maltin, Tim (มีนาคม 2012). "Did the Titanic Sink Because of an Optical Illusion?". Smithsonian. Smithsonian Institution.