ผลต่างระหว่างรุ่นของ "ผู้ใช้:2ndoct/กระบะทราย 4"

ป้ายระบุ: เครื่องมือแก้ไขต้นฉบับปี 2560 |

ไม่มีความย่อการแก้ไข ป้ายระบุ: เพิ่มยูอาร์แอล wikipedia.org เครื่องมือแก้ไขต้นฉบับปี 2560 |

||

| บรรทัด 5: | บรรทัด 5: | ||

ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงเป็นส่วนสำคัญของความอยุติธรรมทางเพศและอุดมการณ์และเป็นพื้นฐานของการกดขี่ผ้หญิงในสังคมที่ชายเป็นใหญ่ ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงได้แสดงออกมาได้หลายทาง ตั้งแต่เรื่องตลกจนถึงสื่อลามกจยกระทั่งความรุนแรงและการดูถูกตัวเองที่ผู้หญิงรู้สึกกับร่างการของพวกเธอ{{quote|ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงเป็นส่วนสำคัญของความอยุติธรรมทางเพศและอุดมการณ์และเป็นพื้นฐานของการกดขี่ผ้หญิงในสังคมที่ชายเป็นใหญ่ ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงได้แสดงออกมาได้หลายทาง ตั้งแต่เรื่องตลกจนถึงสื่อลามก กระทั่งความรุนแรงและการดูถูกตัวเองที่ผู้หญิงรู้สึกกับร่างการของพวกเธอ<ref>{{cite journal | url = https://books.google.com/?id=V1kiW7x6J1MC&pg=PA197&dq=allan+johnson+misogyny#v=onepage&q&f=false | title = The Blackwell dictionary of sociology: A user's guide to sociological language | isbn = 978-0-631-21681-0 | author1 = Johnson | first1 = Allan G | year = 2000 | accessdate = November 21, 2011}}, ("ideology" in all small capitals in original).</ref>}}พจนานุกรมได้อธิบายความหมายของคำว่า misogyny ว่าคือความเกลียดชังผู้หญิง<ref>''The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press (Oxford Univ. Press), [4th] ed. 1993 ({{ISBN|0-19-861271-0}})) (''SOED'') ("[h]atred of women").</ref><ref>''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'' (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1992 ({{ISBN|0-395-44895-6}})) ("[h]atred of women").</ref><ref>''Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged'' (G. & C. Merriam, 1966) ("a hatred of women").</ref> และความเกลียด ไม่ชอบ หรือไม่ไว้ใจผู้หญิง<ref>''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary'' (N.Y.: Random House, 2d ed. 2001 ({{ISBN|0-375-42566-7}})).</ref> |

ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงเป็นส่วนสำคัญของความอยุติธรรมทางเพศและอุดมการณ์และเป็นพื้นฐานของการกดขี่ผ้หญิงในสังคมที่ชายเป็นใหญ่ ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงได้แสดงออกมาได้หลายทาง ตั้งแต่เรื่องตลกจนถึงสื่อลามกจยกระทั่งความรุนแรงและการดูถูกตัวเองที่ผู้หญิงรู้สึกกับร่างการของพวกเธอ{{quote|ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงเป็นส่วนสำคัญของความอยุติธรรมทางเพศและอุดมการณ์และเป็นพื้นฐานของการกดขี่ผ้หญิงในสังคมที่ชายเป็นใหญ่ ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงได้แสดงออกมาได้หลายทาง ตั้งแต่เรื่องตลกจนถึงสื่อลามก กระทั่งความรุนแรงและการดูถูกตัวเองที่ผู้หญิงรู้สึกกับร่างการของพวกเธอ<ref>{{cite journal | url = https://books.google.com/?id=V1kiW7x6J1MC&pg=PA197&dq=allan+johnson+misogyny#v=onepage&q&f=false | title = The Blackwell dictionary of sociology: A user's guide to sociological language | isbn = 978-0-631-21681-0 | author1 = Johnson | first1 = Allan G | year = 2000 | accessdate = November 21, 2011}}, ("ideology" in all small capitals in original).</ref>}}พจนานุกรมได้อธิบายความหมายของคำว่า misogyny ว่าคือความเกลียดชังผู้หญิง<ref>''The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press (Oxford Univ. Press), [4th] ed. 1993 ({{ISBN|0-19-861271-0}})) (''SOED'') ("[h]atred of women").</ref><ref>''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'' (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1992 ({{ISBN|0-395-44895-6}})) ("[h]atred of women").</ref><ref>''Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged'' (G. & C. Merriam, 1966) ("a hatred of women").</ref> และความเกลียด ไม่ชอบ หรือไม่ไว้ใจผู้หญิง<ref>''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary'' (N.Y.: Random House, 2d ed. 2001 ({{ISBN|0-375-42566-7}})).</ref> |

||

== Historical usage == |

|||

=== Classical Greece === |

|||

[[File:Seated_Euripides_Louvre_Ma343.jpg|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Seated_Euripides_Louvre_Ma343.jpg|left|thumb|[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euripides Euripides]]] |

|||

In his book ''City of Sokrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens'', J.W. Roberts argues that older than tragedy and comedy was a misogynistic tradition in Greek literature, reaching back at least as far as [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hesiod Hesiod].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=73kTsV4FdrQC&pg=PA22&dq=Sokrates+misogyny+misogynist#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=City of Sokrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens|isbn=978-0-203-19479-9|author1=Roberts|first1=J.W|date=2002-06-01}}</ref> The term ''misogyny'' itself comes directly into English from the Ancient Greek word ''misogunia'' ({{lang|grc|μισογυνία}}), which survives in several passages. |

|||

The earlier, longer, and more complete passage comes from a moral tract known as ''On Marriage'' (''c''. 150 BC) by the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoicism stoic] philosopher [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antipater_of_Tarsus Antipater of Tarsus].<ref>The ''[[editio princeps]]'' is on page 255 of volume three of ''[[Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta]]'' (''SVF'', Old Stoic Fragments), see [[Misogyny#External links|External links]].</ref><ref name="Deming">A recent critical text with translation is in [https://books.google.com/books?id=u_6a-sMDv6AC&pg=PA221&lpg=PA221&dq=appendix+a+antipater+of+tarsus&source=web&ots=JlCnsyRBGf&sig=7zsKzMVEBnV3tHag9z7E4cWCeLs&hl=en Appendix A] to Will Deming, ''Paul on Marriage and Celibacy: The Hellenistic Background of 1 Corinthians 7'', pp. 221–226. ''Misogunia'' appears in the [[accusative case]] on page 224 of Deming, as the fifth word in line 33 of his Greek text. It is split over lines 25–26 in von Arnim.</ref> Antipater argues that marriage is the foundation of the state, and considers it to be based on divine ([./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polytheism polytheistic]) decree. He uses ''misogunia'' to describe the sort of writing the tragedian [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euripides Euripides] eschews, stating that he "reject[s] the hatred of women in his writing" (ἀποθέμενος τὴν ἐν τῷ γράφειν μισογυνίαν). He then offers an example of this, quoting from a lost play of Euripides in which the merits of a dutiful wife are praised.<ref name="Deming" /><ref>38-43, fr. 63, in von Arnim, J. (ed.). ''Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta.'' Vol. 3. Leipzig: Teubner, 1903.</ref> |

|||

The other surviving use of the original Greek word is by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chrysippus Chrysippus], in a fragment from ''On affections'', quoted by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galen Galen] in ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippocrates Hippocrates] on Affections''.<ref>''SVF'' 3:103. ''Misogyny'' is the first word on the page.</ref> Here, ''misogyny'' is the first in a short list of three "disaffections"—women (''misogunia''), wine (''misoinia'', μισοινία) and humanity (''misanthrōpia'', μισανθρωπία). Chrysippus' point is more abstract than Antipater's, and Galen quotes the passage as an example of an opinion contrary to his own. What is clear, however, is that he groups hatred of women with hatred of humanity generally, and even hatred of wine. "It was the prevailing medical opinion of his day that wine strengthens body and soul alike."<ref name="Tieleman">Teun L. Tieleman, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=BBiw96gj8gkC&printsec=frontcover&dq=chrysippus+on+affections&sig=6f6Y84rR_VZzorWxiGfFMYViuvM Chrysippus' on Affections:] Reconstruction and Interpretations'', (Leiden: [[Brill Publishers]], 2003), p. 162. {{ISBN|90-04-12998-7}}</ref> So Chrysippus, like his fellow stoic Antipater, views misogyny negatively, as a [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disease disease]; a dislike of something that is good. It is this issue of conflicted or alternating emotions that was philosophically contentious to the ancient writers. Ricardo Salles suggests that the general stoic view was that "[a] man may not only alternate between philogyny and misogyny, philanthropy and misanthropy, but be prompted to each by the other."<ref>Ricardo Salles, ''Metaphysics, Soul, and Ethics in Ancient Thought: Themes from the Work of Richard Sorabji'', (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005), 485.</ref> |

|||

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle Aristotle] has also been accused of being a misogynist; he has written that women were inferior to men. According to Cynthia Freeland (1994):{{quote|Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity': which contributes only matter and not form to the generation of offspring; that in general 'a woman is perhaps an inferior being'; that female characters in a tragedy will be inappropriate if they are too brave or too clever[.]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-femhist/#Mis |title=Feminist History of Philosophy (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) |publisher=Plato.stanford.edu |date= |accessdate=2013-10-01}}</ref>}}In the ''Routledge philosophy guidebook to Plato and the Republic'', Nickolas Pappas describes the "problem of misogyny" and states:{{quote|In the ''Apology'', Socrates calls those who plead for their lives in court "no better than women" (35b)... The ''Timaeus'' warns men that if they live immorally they will be reincarnated as women (42b-c; cf. 75d-e). The ''Republic'' contains a number of comments in the same spirit (387e, 395d-e, 398e, 431b-c, 469d), evidence of nothing so much as of contempt toward women. Even Socrates' words for his bold new proposal about marriage... suggest that the women are to be "held in common" by men. He never says that the men might be held in common by the women... We also have to acknowledge Socrates' insistence that men surpass women at any task that both sexes attempt (455c, 456a), and his remark in Book 8 that one sign of democracy's moral failure is the sexual equality it promotes (563b).<ref>{{Cite book | url = https://books.google.com/?id=VujWajIWxkUC&pg=PA109&dq=Socrates+misogyny+misogynist#v=onepage&q&f=false | title = Routledge philosophy guidebook to Plato and the Republic | isbn = 978-0-415-29996-1 | author1 = Pappas | first1 = Nickolas | date = 2003-09-09}}</ref>}}''Misogynist'' is also found in the Greek—''misogunēs'' ({{lang|grc|μισογύνης}})—in ''Deipnosophistae'' (above) and in [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plutarch Plutarch]'s ''Parallel Lives'', where it is used as the title of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heracles Heracles] in the history of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phocion Phocion]. It was the title of a play by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menander Menander], which we know of from book seven (concerning [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandria Alexandria]) of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strabo Strabo]'s 17 volume ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geographica Geography]'',<ref name="Liddell">[[Henry George Liddell]] and [[Robert Scott (philologist)|Robert Scott]], ''[[A Greek–English Lexicon]]'' (''LSJ''), revised and augmented by Henry Stuart Jones and Roderick McKenzie, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940). {{ISBN|0-19-864226-1}}</ref><ref>[[Strabo]],''[[Geographica (Strabo)|Geography]]'', Book 7 [Alexandria] Chapter 3.</ref> and quotations of Menander by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_of_Alexandria Clement of Alexandria] and [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stobaeus Stobaeus] that relate to marriage.<ref>[[Menander]], [https://books.google.com/books?id=JC11wYBkrhkC&pg=PA268&dq=The+Misogynist+(Misogynes)&sig=y98In1TUseOWVGHrcOOMQ0Vx1dU ''The Plays and Fragments''], translated by Maurice Balme, contributor [[Peter G. McC. Brown|Peter Brown]], [[Oxford University Press]], 2002. {{ISBN|0-19-283983-7}}</ref> A Greek play with a similar name, ''Misogunos'' (Μισόγυνος) or ''Woman-hater'', is reported by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero Marcus Tullius Cicero] (in Latin) and attributed to the poet [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atilia_(gens)#Members_of_the_gens Marcus Atilius].<ref>He is supported (or followed) by [[Theognostus the Grammarian]]'s 9th century ''Canones'', edited by [[John Antony Cramer]], ''Anecdota Graeca e codd. manuscriptis bibliothecarum Oxoniensium'', vol. 2, ([[Oxford University Press]], 1835), p. 88.</ref> |

|||

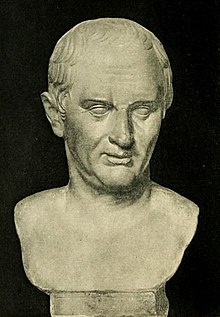

[[File:CiceroBust.jpg|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CiceroBust.jpg|thumb|[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero Marcus Tullius Cicero]]] |

|||

Cicero reports that Greek philosophers considered misogyny to be caused by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gynophobia gynophobia], a fear of women.<ref name="Cicero">[[Cicero|Marcus Tullius Cicero]], ''[[Tusculanae Quaestiones]]'', Book 4, Chapter 11.</ref>{{quote|It is the same with other diseases; as the desire of glory, a passion for women, to which the Greeks give the name of ''philogyneia'': and thus all other diseases and sicknesses are generated. But those feelings which are the contrary of these are supposed to have fear for their foundation, as a hatred of women, such as is displayed in the ''Woman-hater'' of Atilius; or the hatred of the whole human species, as Timon is reported to have done, whom they call the Misanthrope. Of the same kind is inhospitality. And all these diseases proceed from a certain dread of such things as they hate and avoid.<ref name="Cicero" />|Cicero|''[[Tusculanae Quaestiones]]'', 1st century BC.}}In summary, Greek literature considered misogyny to be a [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disease disease]—an [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-social_behaviour anti-social] condition—in that it ran contrary to their perceptions of the value of women as wives and of the family as the foundation of society. These points are widely noted in the secondary literature.<ref name="Deming" /> |

|||

== Religion == |

|||

{{See also|Feminist theology|Sex differences in religion}} |

|||

=== Ancient Greek === |

|||

In ''Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice'', [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Holland_(writer) Jack Holland] argues that there is evidence of misogyny in the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mythology mythology] of the ancient world. In [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_mythology Greek mythology] according to Hesiod, the human race had already experienced a peaceful, autonomous existence as a companion to the gods before the creation of women. When [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prometheus Prometheus] decides to steal the secret of fire from the gods, [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeus Zeus] becomes infuriated and decides to punish humankind with an "evil thing for their delight". This "evil thing" is [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandora Pandora], the first woman, who carried a jar (usually described—incorrectly—as a box) which she was told to never open. [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epimetheus_(mythology) Epimetheus] (the brother of Prometheus) is overwhelmed by her beauty, disregards Prometheus' warnings about her, and marries her. Pandora cannot resist peeking into the jar, and by opening it she unleashes into the world all evil; [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Childbirth labour], [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illness sickness], [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_age old age], and [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death death].<ref>Holland, J: ''Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice'', pp. 12–13. Avalon Publishing Group, 2006.</ref> |

|||

=== Buddhism === |

|||

{{Main article|Women in Buddhism}}In his book ''The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender'', professor Bernard Faure of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_University Columbia University] argued generally that "Buddhism is paradoxically neither as sexist nor as egalitarian as is usually thought." He remarked, "Many feminist scholars have emphasized the misogynistic (or at least androcentric) nature of Buddhism" and stated that Buddhism morally exalts its male monks while the mothers and wives of the monks also have important roles. Additionally, he wrote: |

|||

{{quote|While some scholars see Buddhism as part of a movement of emancipation, others see it as a source of oppression. Perhaps this is only a distinction between optimists and pessimists, if not between idealists and realists... As we begin to realize, the term "Buddhism" does not designate a monolithic entity, but covers a number of doctrines, ideologies, and practices--some of which seem to invite, tolerate, and even cultivate "otherness" on their margins.<ref name=bernard>{{cite web |url=http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/i7538.html |title=Sample Chapter for Faure, B.: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender |publisher=Press.princeton.edu |date= |accessdate=2013-10-01 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20131005011657/http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/i7538.html |archivedate=2013-10-05 |df= }}</ref>}} |

|||

=== Christianity === |

|||

[[File:Maria_laach_eva_teufel.jpg|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Maria_laach_eva_teufel.jpg|thumb|[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eve Eve] rides astride the Serpent on a capital in [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Laach_Abbey Laach Abbey church], 13th century]] |

|||

{{Main article|Gender roles in Christianity}}{{See also|Complementarianism|Christian egalitarianism}}Differences in tradition and interpretations of scripture have caused sects of Christianity to differ in their beliefs with regard their treatment of women. |

|||

In ''The Troublesome Helpmate'', Katharine M. Rogers argues that Christianity is misogynistic, and she lists what she says are specific examples of misogyny in the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauline_epistles Pauline epistles]. She states: |

|||

{{quote|The foundations of early Christian misogyny — its guilt about sex, its insistence on female subjection, its dread of female seduction — are all in St. Paul's epistles.<ref>Rogers, Katharine M. ''The Troublesome Helpmate: A History of Misogyny in Literature,'' 1966.</ref>}} |

|||

In K. K. Ruthven's ''Feminist Literary Studies: An Introduction'', Ruthven makes reference to Rogers' book and argues that the "legacy of Christian misogyny was consolidated by the so-called 'Fathers' of the Church, like [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tertullian Tertullian], who thought a woman was not only 'the gateway of the devil' but also 'a temple built over a sewer'."<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=clOT7Hg2CfAC&pg=PA83&dq=christian+misogyny#v=onepage&q=christian%20misogyny&f=false|title=Feminist literary studies: An introduction|isbn=978-0-521-39852-7|author1=Ruthven|first1=K. K|year=1990}}</ref> |

|||

However, some other scholars have argued that Christianity does not include misogynistic principles, or at least that a proper interpretation of Christianity would not include misogynistic principles. David M. Scholer, a biblical scholar at [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fuller_Theological_Seminary Fuller Theological Seminary], stated that the verse Galatians 3:28 ("There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus") is "the fundamental Pauline theological basis for the inclusion of women and men as equal and mutual partners in all of the ministries of the church."<ref name="CBMW">{{cite web|title=Galatians 3:28 – prooftext or context?|url=http://cbmw.org/staff/|publisher=The council on biblical manhood and womanhood|accessdate=January 6, 2015|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150206045217/http://cbmw.org/staff/|archivedate=February 6, 2015|df=}}</ref><ref>Hove, Richard. ''Equality in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the Gender Dispute'' (Wheaton: Crossway, 1999), p. 17.</ref> In his book ''Equality in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the Gender Dispute'', Richard Hove argues that—while Galatians 3:28 does mean that one's sex does not affect salvation—"there remains a pattern in which the wife is to emulate the church's submission to Christ ({{bibleverse||Eph|5:21-33|KJV}}) and the husband is to emulate Christ's love for the church."<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=WcyqvWfJnyYC&pg=PA283&dq=ken+campbell+3:28+Rochard+Hove#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Marriage and family in the biblical world|isbn=978-0-8308-2737-4|author1=Campbell|first1=Ken M|date=October 1, 2003}}</ref> |

|||

In ''Christian Men Who Hate Women'', clinical psychologist Margaret J. Rinck has written that Christian social culture often allows a misogynist "misuse of the biblical ideal of submission". However, she argues that this a distortion of the "healthy relationship of mutual submission" which is actually specified in Christian doctrine, where "[l]ove is based on a deep, mutual respect as the guiding principle behind all decisions, actions, and plans".<ref>{{cite book|title=Christian Men Who Hate Women: Healing Hurting Relationships|first=Margaret J.|last=Rinck|publisher=[[Zondervan]]|year=1990|isbn=978-0-310-51751-1|pages=81–85}}</ref> Similarly, Catholic scholar [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_West Christopher West] argues that "male domination violates God's plan and is the specific result of sin".<ref>{{cite book|last=Weigel|first=Christopher West ; with a foreword by George|title=Theology of the body explained : a commentary on John Paul II's "Gospel of the body"|year=2003|publisher=Gracewing|location=Leominster, Herefordshire|isbn=978-0-85244-600-3}}</ref> |

|||

=== Islam === |

|||

{{Main article|Women in Islam}}{{See also|Namus|Islam and domestic violence}}The fourth chapter (or ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sura sura]'') of the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quran Quran] is called "Women" ([./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An-Nisa An-Nisa]). The [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An-Nisa,_34 34th verse] is a key verse in feminist criticism of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam Islam].<ref>"Verse 34 of Chapter 4 is an oft-cited Verse in the Qur'an used to demonstrate that Islam is structurally patriarchal, and thus Islam internalizes male dominance." Dahlia Eissa, "[http://www.wluml.org/node/443#_ftn42 Constructing the Notion of Male Superiority over Women in Islam]: The influence of sex and gender stereotyping in the interpretation of the Qur'an and the implications for a modernist exegesis of rights", Occasional Paper 11 in ''Occasional Papers'' (Empowerment International, 1999).</ref> The verse reads: "Men are the maintainers of women because Allah has made some of them to excel others and because they spend out of their property; the good women are therefore obedient, guarding the unseen as Allah has guarded; and (as to) those on whose part you fear desertion, admonish them, and leave them alone in the sleeping-places and beat them; then if they obey you, do not seek a way against them; surely Allah is High, Great." |

|||

In his book ''Popular Islam and Misogyny: A Case Study of Bangladesh'', Taj Hashmi discusses misogyny in relation to Muslim culture (and to [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bangladesh Bangladesh] in particular), writing: |

|||

{{quote|[T]hanks to the subjective interpretations of the Quran (almost exclusively by men), the preponderance of the misogynic mullahs and the regressive Shariah law in most "Muslim" countries, Islam is synonymously known as a promoter of misogyny in its worst form. Although there is no way of defending the so-called "great" traditions of Islam as libertarian and egalitarian with regard to women, we may draw a line between the Quranic texts and the corpus of avowedly misogynic writing and spoken words by the mullah having very little or no relevance to the Quran.<ref>Hashmi, Taj. ''[http://www.mukto-mona.com/Articles/taj_hashmi/Popular_Islam_and_Misogyn1.pdf Popular Islam and Misogyny: A Case Study of Bangladesh]''. Retrieved August 11, 2008.</ref>}} |

|||

In his book ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_god_but_God:_The_Origins,_Evolution,_and_Future_of_Islam No god but God]'', [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Southern_California University of Southern California] professor [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reza_Aslan Reza Aslan] wrote that "misogynistic interpretation" has been persistently attached to An-Nisa, 34 because commentary on the Quran "has been the exclusive domain of Muslim men".<ref name="issue">{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/20/AR2006102001261.html|publisher=Washington Post|title=Clothes Aren't the Issue|date=October 22, 2006|first=Asra Q.|last=Nomani}}</ref> |

|||

=== Sikhism === |

|||

[[File:Sikh_Gurus_with_Bhai_Bala_and_Bhai_Mardana.jpg|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sikh_Gurus_with_Bhai_Bala_and_Bhai_Mardana.jpg|right|thumb|[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guru_Nanak Guru Nanak] in the center, amongst other Sikh figures]] |

|||

{{See also|Women in Sikhism}}Scholars William M. Reynolds and Julie A. Webber have written that [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guru_Nanak Guru Nanak], the founder of the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikh Sikh] faith tradition, was a "fighter for women's rights" that was "in no way misogynistic" in contrast to some of his contemporaries.<ref>{{cite book|page=87|title=Expanding curriculum theory: dis/positions and lines of flight|author=Julie A. Webber|publisher=Psychology Press|year=2004|isbn=978-0-8058-4665-2}}</ref> |

|||

=== Scientology === |

|||

{{See also|Scientology and abortion|Scientology and gender|Scientology and marriage|Scientology and sex}}In his book ''Scientology: A New Slant on Life'', [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L._Ron_Hubbard L. Ron Hubbard] wrote the following passage: |

|||

{{quote|A society in which women are taught anything but the management of a family, the care of men, and the creation of the future generation is a society which is on its way out.</blockquote>}} |

|||

In the same book, he also wrote: |

|||

{{quote|The historian can peg the point where a society begins its sharpest decline at the instant when women begin to take part, on an equal footing with men, in political and business affairs, since this means that the men are decadent and the women are no longer women. This is not a sermon on the role or position of women; it is a statement of bald and basic fact.</blockquote>}} |

|||

These passages, along with other ones of a similar nature from Hubbard, have been criticised by Alan Scherstuhl of ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Village_Voice The Village Voice]'' as expressions of hatred towards women.<ref>{{cite news|title=The Church of Scientology does not want you to see L. Ron Hubbard's woman-hatin' book chapter|publisher=[[The Village Voice]]|first=Alan|last=Scherstuhl|date=June 21, 2010|url=http://blogs.villagevoice.com/runninscared/archives/2010/06/the_church_of_s.php|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100625003539/http://blogs.villagevoice.com/runninscared/archives/2010/06/the_church_of_s.php|archivedate=June 25, 2010|df=}}</ref> However, [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baylor_University Baylor University] professor [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Gordon_Melton J. Gordon Melton] has written that Hubbard later disregarded and abrogated much of his earlier views about women, which Melton views as merely echoes of common prejudices at the time. Melton has also stated that the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_Scientology Church of Scientology] welcomes both genders equally at all levels—from leadership positions to [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auditing_(Scientology) auditing] and so on—since Scientologists view people as [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thetan spiritual beings].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.patheos.com/Library/Scientology/Ethics-Morality-Community/Gender-and-Sexuality.html|title=Gender and Sexuality|publisher=Patheos.com|date=2012-07-26|accessdate=2013-10-01}}</ref> |

|||

== นักปรัชญาและนักคิด (ศตวรรษที่ 17 - 20) == |

== นักปรัชญาและนักคิด (ศตวรรษที่ 17 - 20) == |

||

นักปรัชญาชาวตะวันตกหลายคนถูกกล่าวหาว่ามีความเกลียดชังผู้หญิง รวมทั้ง [[อาริสโตเติล]], [[เรอเน เดการ์ต]],[[โทมัส ฮอบส์]], [[จอห์น ล็อก |

นักปรัชญาชาวตะวันตกหลายคนถูกกล่าวหาว่ามีความเกลียดชังผู้หญิง รวมทั้ง [[อาริสโตเติล]], [[เรอเน เดการ์ต]],[[โทมัส ฮอบส์]], [[จอห์น ล็อก]], [[เดวิด ฮูม]], [[ฌ็อง-ฌัก รูโซ]], [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel|G. W. F. Hegel]], [[อาร์ทูร์ โชเพนเฮาเออร์]], [[ฟรีดริช นีทเชอ]], [[ชาลส์ ดาร์วิน]], [[ซิกมุนด์ ฟรอยด์]], [[Otto Weininger]], [[Oswald Spengler]], และ [[John Lucas (philosopher)|John Lucas]].<ref name="Clack1999">{{cite book|last1=Clack|first1=Beverley|title=Misogyny in the Western Philosophical Tradition: A Reader|date=1999|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|isbn=0-415-92182-1|pages=95–241}}</ref> |

||

=== Aristotle === |

|||

Aristotle believed women were inferior and described them as "deformed males".<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|edition=Spring 2016|title=Feminist History of Philosophy|url=http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/feminism-femhist/|date=2016-01-01|first=Charlotte|last=Witt|first2=Lisa|last2=Shapiro|editor-first=Edward N.|editor-last=Zalta}}</ref><ref name="Smith 467–478">{{Cite journal|title=Plato and Aristotle on the Nature of Women|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236725862|journal=Journal of the History of Philosophy|pages=467–478|volume=21|issue=4|doi=10.1353/hph.1983.0090|first=Nicholas D.|last=Smith|year=1983}}</ref> In his work ''Politics'', he states<blockquote>as regards the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject 4 (1254b13-14).<ref name="Smith 467–478" /></blockquote>Another example is ''Cynthia's catalog'' where Cynthia states "Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity'.<ref name=":0" /> Aristotle believed that men and women naturally differed both physically and mentally. He claimed that women are "more mischievous, less simple, more impulsive ... more compassionate[,] ... more easily moved to tears[,] ... more jealous, more querulous, more apt to scold and to strike[,] ... more prone to despondency and less hopeful[,] ... more void of shame or self-respect, more false of speech, more deceptive, of more retentive memory [and] ... also more wakeful; more shrinking [and] more difficult to rouse to action" than men.<ref>History of Animals, 608b. 1–14</ref> |

|||

=== Jean-Jacques Rousseau === |

|||

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Jacques_Rousseau Jean-Jacques Rousseau] is well known for his views against equal rights for women for example in his treatise ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emile,_or_On_Education Emile]'', he writes: "Always justify the burdens you impose upon girls but impose them anyway... . They must be thwarted from an early age... . They must be exercised to constraint, so that it costs them nothing to stifle all their fantasies to submit them to the will of others." Other quotes consist of "closed up in their houses", "must receive the decisions of fathers and husbands like that of the church".<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Rousseau and Feminist Revision|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241893904|journal=Eighteenth-Century Life|pages=51–54|volume=34|issue=3|doi=10.1215/00982601-2010-012|first=C.|last=Blum|year=2010}}</ref> |

|||

=== Charles Darwin === |

|||

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Darwin Charles Darwin] wrote on the subject female inferiority through the lens of human evolution.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|title=The history of the human female inferiority ideas in evolutionary biology|journal=Rivista di Biologia|date=2002-12-01|issn=0035-6050|pmid=12680306|pages=379–412|volume=95|issue=3|first=Gerald|last=Bergman}}</ref> He noted in his book ''The Descent of Men'': "young of both sexes resembled the adult female in most species" which he extrapolated and further reasoned "males were more evolutionarily advanced than females". Darwin believed all savages, children and women had smaller brains and therefore led more by instinct and less by reason.<ref name=":1" /> Such ideas quickly spread to other scientists such as Professor Carl Vogt of natural sciences at the University of Geneva who argued "the child, the female, and the senile white" had the mental traits of a "grown up Negro", that the female is similar in intellectual capacity and personality traits to both infants and the "lower races" such as blacks while drawing conclusion that women are closely related to lower animals than men and "hence we should discover a greater apelike resemblance if we were to take a female as our standard".<ref name=":1" /> Darwin's beliefs about women were also reflective of his attitudes towards women in general for example his views towards marriage as a young man in which he was quoted ""how should I manage all my business if obligated to go everyday walking with my wife – Ehau!" and that being married was "worse than being a Negro".<ref name=":1" /> Or in other instances his concern of his son marrying a woman named Martineau about which he wrote "... he shall be not much better than her "nigger." Imagine poor Erasmus a nigger to so philosophical and energetic a lady ... Martineau had just returned from a whirlwind tour of America, and was full of married women's property rights ... Perfect equality of rights is part of her doctrine...We must pray for our poor "nigger.""<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

=== Arthur Schopenhauer === |

|||

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Schopenhauer Arthur Schopenhauer] has been noted as a misogynist by many such as the philosopher, critic, and author Tom Grimwood.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|title=The Limits of Misogyny: Schopenhauer, "On Women"|url=http://philpapers.org/rec/GRITLO|journal=Kritike: An Online Journal of Philosophy|date=2008-01-01|pages=131–145|volume=2|issue=2|first=Tom|last=Grimwood|doi=10.3860/krit.v2i2.854}}</ref> In a 2008 article Grimwood wrote published in the philosophical journal of ''Kritique,'' Grimwood argues that Schopenhauer's misogynistic works have largely escaped attention despite being more noticeable than those of other philosophers such as Nietzsche.<ref name=":2" /> For example, he noted Schopenhauer's works where the latter had argued women only have "meagre" reason comparable that of "the animal" "who lives in the present". Other works he noted consisted of Schopenhauer's argument that women's only role in nature is to further the species through childbirth and hence is equipped with the power to seduce and "capture" men.<ref name=":2" /> He goes on to state that women's cheerfulness is chaotic and disruptive which is why it is crucial to exercise obedience to those with rationality. For her to function beyond her rational subjugator is a threat against men as well as other women, he notes. Schopenhauer also thought women's cheerfulness is an expression of her lack of morality and incapability to understand abstract or objective meaning such as art.<ref name=":2" /> This is followed up by his quote "have never been able to produce a single, really great, genuine and original achievement in the fine arts, or bring to anywhere into the world a work of permanent value".<ref name=":2" /> Arthur Schopenhauer also blamed women for the fall of King Louis XIII and triggering the French Revolution, in which he was later quoted as saying:<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

"At all events, a false position of the female sex, such as has its most acute symptom in our lady-business, is a fundamental defect of the state of society. Proceeding from the heart of this, it is bound to spread its noxious influence to all parts."<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

Schopenhauer has also been accused of misogyny for his essay "On Women" (Über die Weiber), in which he expressed his opposition to what he called "Teutonico-Christian stupidity" on female affairs. He argued that women are "by nature meant to obey" as they are "childish, frivolous, and short sighted".<ref name="Clack1999">{{cite book|last1=Clack|first1=Beverley|title=Misogyny in the Western Philosophical Tradition: A Reader|date=1999|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|isbn=978-0-415-92182-4|pages=95–241}}</ref> He claimed that no woman had ever produced great art or "any work of permanent value".<ref name="Clack1999" /> He also argued that women did not possess any real beauty:<ref>{{cite book|last1=Durant|first1=Will|title=The Story of Philosophy|date=1983|publisher=Simon and Schuster|location=New York, N.Y.|isbn=978-0-671-20159-3|page=257}}</ref> |

|||

{{quote|It is only a man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual impulse that could give the name of the ''fair sex'' to that under-sized, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race; for the whole beauty of the sex is bound up with this impulse. Instead of calling them beautiful there would be more warrant for describing women as the unaesthetic sex.}} |

|||

=== Nietzsche === |

|||

{{Main article|Friedrich Nietzsche's views on women}}In ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beyond_Good_and_Evil Beyond Good and Evil]'', [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Nietzsche Friedrich Nietzsche] stated that stricter controls on women was a condition of "every elevation of culture".<ref>{{cite book|last=Nietzsche|first=Friedrich|year=1886|title=Beyond Good and Evil|url=http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4363/4363-h/4363-h.htm|location=Germany|accessdate=January 23, 2014}}</ref> In his ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thus_Spoke_Zarathustra Thus Spoke Zarathustra]'', he has a female character say "You are going to women? Do not forget the whip!"<ref>{{cite book|last=Burgard|first=Peter J.|title=Nietzsche and the Feminine|date=May 1994|publisher=University of Virginia Press|location=Charlottesville, VA|isbn=978-0-8139-1495-4|page=11}}</ref> In ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twilight_of_the_Idols Twilight of the Idols]'', Nietzsche writes "Women are considered profound. Why? Because we never fathom their depths. But women aren't even shallow."<ref>{{cite book|last=Nietzsche|first=Friedrich|year=1889|title=Twilight of the Idols|url=http://www.handprint.com/SC/NIE/GotDamer.html|location=Germany|isbn=978-0-14-044514-5|accessdate=January 23, 2014}}</ref> There is controversy over the questions of whether or not this amounts to misogyny, whether his polemic against women is meant to be taken literally, and the exact nature of his opinions of women.<ref name="Holub">Robert C. Holub, ''Nietzsche and The Women's Question''. [https://web.archive.org/web/20060907092224/http://www-learning.berkeley.edu/robertholub/teaching/syllabi/Lecture_Nietzsche_Women.pdf Coursework for Berkley University.]</ref> |

|||

=== Hegel === |

|||

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Wilhelm_Friedrich_Hegel Hegel's] view of women can be characterized as misogynistic.<ref>{{cite book|last=Gallagher|first=Shaun|title=Hegel, history, and interpretation|year=1997|publisher=SUNY Press|isbn=978-0-7914-3381-2|page=235|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OdlvNHnC6KMC&pg=PA235&dq=Hegel+misogyny+misogynistic#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> Passages from Hegel's ''[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elements_of_the_Philosophy_of_Right Elements of the Philosophy of Right]'' illustrate the criticism:<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/?id=rJqm5iQcsqoC&pg=PA3&dq=Hegel+misogyny+misogynistic#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Feminist Reflections on the History of Philosophy|isbn=978-1-4020-2488-7|author1=Alanen|first1=Lilli|last2=Witt|first2=Charlotte|year=2004}}</ref> |

|||

{{Quote|text=Women are capable of education, but they are not made for activities which demand a universal faculty such as the more advanced sciences, philosophy and certain forms of artistic production... Women regulate their actions not by the demands of universality, but by arbitrary inclinations and opinions.}} |

|||

<br /> |

|||

== Online misogyny == |

|||

== อ้างอิง == |

== อ้างอิง == |

||

รุ่นแก้ไขเมื่อ 22:36, 9 มีนาคม 2562

อาการเกลียดชังผู้หญิง (อังกฤษ: Misogyny) คือความเกลียดชัง การดูหมิ่นหรืออคติกับผู้หญิงหรือเด็กผู้หญิง ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงอาจแสดงออกได้หลายวิธีเช่น การกัดกันทางสังคม การกีดกันทางเพศ ความรุนแรง ระบบชายเป็นศูนย์กลาง (androcentrism) ระบบนิยมชาย(patriarchy) สิทธิพิเศษสำหรับผู้ชาย male privilege การดูถูกผู้หญิง ความรุนแรงต่อผู้หญิง การทำให้ผู้หญิงเป็นวัตถุทางเพศ[1][2] ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงมักพบเห็นได้ในคัมภีร์ศักดิ์สิทธิ์ทางศาสนา ปรัมปราวิทยา และนักปรัชญาและนักคิดตะวันตกหลายคนต่างก็ถูกกล่าวว่าเป็นผู้มีความเกลียดชังผู้หญิง[1][3]

คำนิยาม

นักสังคมวิทยาอลัน จี จอห์นสันกล่าวไว้ว่า "ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงเป็นทัศนคติทางวัฒนธรรมของความเกลียดชังหญิงเนื่องจากพวกเธอเป็นหญิง" อลันอ้างว่า

ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงเป็นส่วนสำคัญของความอยุติธรรมทางเพศและอุดมการณ์และเป็นพื้นฐานของการกดขี่ผ้หญิงในสังคมที่ชายเป็นใหญ่ ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงได้แสดงออกมาได้หลายทาง ตั้งแต่เรื่องตลกจนถึงสื่อลามกจยกระทั่งความรุนแรงและการดูถูกตัวเองที่ผู้หญิงรู้สึกกับร่างการของพวกเธอ

ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงเป็นส่วนสำคัญของความอยุติธรรมทางเพศและอุดมการณ์และเป็นพื้นฐานของการกดขี่ผ้หญิงในสังคมที่ชายเป็นใหญ่ ความเกลียดชังผู้หญิงได้แสดงออกมาได้หลายทาง ตั้งแต่เรื่องตลกจนถึงสื่อลามก กระทั่งความรุนแรงและการดูถูกตัวเองที่ผู้หญิงรู้สึกกับร่างการของพวกเธอ[4]

พจนานุกรมได้อธิบายความหมายของคำว่า misogyny ว่าคือความเกลียดชังผู้หญิง[5][6][7] และความเกลียด ไม่ชอบ หรือไม่ไว้ใจผู้หญิง[8]

Historical usage

Classical Greece

In his book City of Sokrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens, J.W. Roberts argues that older than tragedy and comedy was a misogynistic tradition in Greek literature, reaching back at least as far as [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hesiod Hesiod].[9] The term misogyny itself comes directly into English from the Ancient Greek word misogunia (μισογυνία), which survives in several passages.

The earlier, longer, and more complete passage comes from a moral tract known as On Marriage (c. 150 BC) by the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoicism stoic] philosopher [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antipater_of_Tarsus Antipater of Tarsus].[10][11] Antipater argues that marriage is the foundation of the state, and considers it to be based on divine ([./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polytheism polytheistic]) decree. He uses misogunia to describe the sort of writing the tragedian [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euripides Euripides] eschews, stating that he "reject[s] the hatred of women in his writing" (ἀποθέμενος τὴν ἐν τῷ γράφειν μισογυνίαν). He then offers an example of this, quoting from a lost play of Euripides in which the merits of a dutiful wife are praised.[11][12]

The other surviving use of the original Greek word is by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chrysippus Chrysippus], in a fragment from On affections, quoted by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galen Galen] in [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippocrates Hippocrates] on Affections.[13] Here, misogyny is the first in a short list of three "disaffections"—women (misogunia), wine (misoinia, μισοινία) and humanity (misanthrōpia, μισανθρωπία). Chrysippus' point is more abstract than Antipater's, and Galen quotes the passage as an example of an opinion contrary to his own. What is clear, however, is that he groups hatred of women with hatred of humanity generally, and even hatred of wine. "It was the prevailing medical opinion of his day that wine strengthens body and soul alike."[14] So Chrysippus, like his fellow stoic Antipater, views misogyny negatively, as a [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disease disease]; a dislike of something that is good. It is this issue of conflicted or alternating emotions that was philosophically contentious to the ancient writers. Ricardo Salles suggests that the general stoic view was that "[a] man may not only alternate between philogyny and misogyny, philanthropy and misanthropy, but be prompted to each by the other."[15]

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle Aristotle] has also been accused of being a misogynist; he has written that women were inferior to men. According to Cynthia Freeland (1994):

Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity': which contributes only matter and not form to the generation of offspring; that in general 'a woman is perhaps an inferior being'; that female characters in a tragedy will be inappropriate if they are too brave or too clever[.][16]

In the Routledge philosophy guidebook to Plato and the Republic, Nickolas Pappas describes the "problem of misogyny" and states:

In the Apology, Socrates calls those who plead for their lives in court "no better than women" (35b)... The Timaeus warns men that if they live immorally they will be reincarnated as women (42b-c; cf. 75d-e). The Republic contains a number of comments in the same spirit (387e, 395d-e, 398e, 431b-c, 469d), evidence of nothing so much as of contempt toward women. Even Socrates' words for his bold new proposal about marriage... suggest that the women are to be "held in common" by men. He never says that the men might be held in common by the women... We also have to acknowledge Socrates' insistence that men surpass women at any task that both sexes attempt (455c, 456a), and his remark in Book 8 that one sign of democracy's moral failure is the sexual equality it promotes (563b).[17]

Misogynist is also found in the Greek—misogunēs (μισογύνης)—in Deipnosophistae (above) and in [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plutarch Plutarch]'s Parallel Lives, where it is used as the title of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heracles Heracles] in the history of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phocion Phocion]. It was the title of a play by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menander Menander], which we know of from book seven (concerning [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandria Alexandria]) of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strabo Strabo]'s 17 volume [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geographica Geography],[18][19] and quotations of Menander by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_of_Alexandria Clement of Alexandria] and [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stobaeus Stobaeus] that relate to marriage.[20] A Greek play with a similar name, Misogunos (Μισόγυνος) or Woman-hater, is reported by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero Marcus Tullius Cicero] (in Latin) and attributed to the poet [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atilia_(gens)#Members_of_the_gens Marcus Atilius].[21]

Cicero reports that Greek philosophers considered misogyny to be caused by [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gynophobia gynophobia], a fear of women.[22]

It is the same with other diseases; as the desire of glory, a passion for women, to which the Greeks give the name of philogyneia: and thus all other diseases and sicknesses are generated. But those feelings which are the contrary of these are supposed to have fear for their foundation, as a hatred of women, such as is displayed in the Woman-hater of Atilius; or the hatred of the whole human species, as Timon is reported to have done, whom they call the Misanthrope. Of the same kind is inhospitality. And all these diseases proceed from a certain dread of such things as they hate and avoid.[22]

— Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 1st century BC.

In summary, Greek literature considered misogyny to be a [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disease disease]—an [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-social_behaviour anti-social] condition—in that it ran contrary to their perceptions of the value of women as wives and of the family as the foundation of society. These points are widely noted in the secondary literature.[11]

Religion

Ancient Greek

In Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice, [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Holland_(writer) Jack Holland] argues that there is evidence of misogyny in the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mythology mythology] of the ancient world. In [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_mythology Greek mythology] according to Hesiod, the human race had already experienced a peaceful, autonomous existence as a companion to the gods before the creation of women. When [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prometheus Prometheus] decides to steal the secret of fire from the gods, [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeus Zeus] becomes infuriated and decides to punish humankind with an "evil thing for their delight". This "evil thing" is [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pandora Pandora], the first woman, who carried a jar (usually described—incorrectly—as a box) which she was told to never open. [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epimetheus_(mythology) Epimetheus] (the brother of Prometheus) is overwhelmed by her beauty, disregards Prometheus' warnings about her, and marries her. Pandora cannot resist peeking into the jar, and by opening it she unleashes into the world all evil; [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Childbirth labour], [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illness sickness], [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_age old age], and [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death death].[23]

Buddhism

In his book The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, professor Bernard Faure of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_University Columbia University] argued generally that "Buddhism is paradoxically neither as sexist nor as egalitarian as is usually thought." He remarked, "Many feminist scholars have emphasized the misogynistic (or at least androcentric) nature of Buddhism" and stated that Buddhism morally exalts its male monks while the mothers and wives of the monks also have important roles. Additionally, he wrote:

While some scholars see Buddhism as part of a movement of emancipation, others see it as a source of oppression. Perhaps this is only a distinction between optimists and pessimists, if not between idealists and realists... As we begin to realize, the term "Buddhism" does not designate a monolithic entity, but covers a number of doctrines, ideologies, and practices--some of which seem to invite, tolerate, and even cultivate "otherness" on their margins.[24]

Christianity

Differences in tradition and interpretations of scripture have caused sects of Christianity to differ in their beliefs with regard their treatment of women.

In The Troublesome Helpmate, Katharine M. Rogers argues that Christianity is misogynistic, and she lists what she says are specific examples of misogyny in the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauline_epistles Pauline epistles]. She states:

The foundations of early Christian misogyny — its guilt about sex, its insistence on female subjection, its dread of female seduction — are all in St. Paul's epistles.[25]

In K. K. Ruthven's Feminist Literary Studies: An Introduction, Ruthven makes reference to Rogers' book and argues that the "legacy of Christian misogyny was consolidated by the so-called 'Fathers' of the Church, like [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tertullian Tertullian], who thought a woman was not only 'the gateway of the devil' but also 'a temple built over a sewer'."[26]

However, some other scholars have argued that Christianity does not include misogynistic principles, or at least that a proper interpretation of Christianity would not include misogynistic principles. David M. Scholer, a biblical scholar at [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fuller_Theological_Seminary Fuller Theological Seminary], stated that the verse Galatians 3:28 ("There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus") is "the fundamental Pauline theological basis for the inclusion of women and men as equal and mutual partners in all of the ministries of the church."[27][28] In his book Equality in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the Gender Dispute, Richard Hove argues that—while Galatians 3:28 does mean that one's sex does not affect salvation—"there remains a pattern in which the wife is to emulate the church's submission to Christ (Eph 5:21–33) and the husband is to emulate Christ's love for the church."[29]

In Christian Men Who Hate Women, clinical psychologist Margaret J. Rinck has written that Christian social culture often allows a misogynist "misuse of the biblical ideal of submission". However, she argues that this a distortion of the "healthy relationship of mutual submission" which is actually specified in Christian doctrine, where "[l]ove is based on a deep, mutual respect as the guiding principle behind all decisions, actions, and plans".[30] Similarly, Catholic scholar [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_West Christopher West] argues that "male domination violates God's plan and is the specific result of sin".[31]

Islam

The fourth chapter (or [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sura sura]) of the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quran Quran] is called "Women" ([./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An-Nisa An-Nisa]). The [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/An-Nisa,_34 34th verse] is a key verse in feminist criticism of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam Islam].[32] The verse reads: "Men are the maintainers of women because Allah has made some of them to excel others and because they spend out of their property; the good women are therefore obedient, guarding the unseen as Allah has guarded; and (as to) those on whose part you fear desertion, admonish them, and leave them alone in the sleeping-places and beat them; then if they obey you, do not seek a way against them; surely Allah is High, Great."

In his book Popular Islam and Misogyny: A Case Study of Bangladesh, Taj Hashmi discusses misogyny in relation to Muslim culture (and to [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bangladesh Bangladesh] in particular), writing:

[T]hanks to the subjective interpretations of the Quran (almost exclusively by men), the preponderance of the misogynic mullahs and the regressive Shariah law in most "Muslim" countries, Islam is synonymously known as a promoter of misogyny in its worst form. Although there is no way of defending the so-called "great" traditions of Islam as libertarian and egalitarian with regard to women, we may draw a line between the Quranic texts and the corpus of avowedly misogynic writing and spoken words by the mullah having very little or no relevance to the Quran.[33]

In his book [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_god_but_God:_The_Origins,_Evolution,_and_Future_of_Islam No god but God], [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Southern_California University of Southern California] professor [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reza_Aslan Reza Aslan] wrote that "misogynistic interpretation" has been persistently attached to An-Nisa, 34 because commentary on the Quran "has been the exclusive domain of Muslim men".[34]

Sikhism

Scholars William M. Reynolds and Julie A. Webber have written that [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guru_Nanak Guru Nanak], the founder of the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikh Sikh] faith tradition, was a "fighter for women's rights" that was "in no way misogynistic" in contrast to some of his contemporaries.[35]

Scientology

In his book Scientology: A New Slant on Life, [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L._Ron_Hubbard L. Ron Hubbard] wrote the following passage:

A society in which women are taught anything but the management of a family, the care of men, and the creation of the future generation is a society which is on its way out.

In the same book, he also wrote:

The historian can peg the point where a society begins its sharpest decline at the instant when women begin to take part, on an equal footing with men, in political and business affairs, since this means that the men are decadent and the women are no longer women. This is not a sermon on the role or position of women; it is a statement of bald and basic fact.

These passages, along with other ones of a similar nature from Hubbard, have been criticised by Alan Scherstuhl of [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Village_Voice The Village Voice] as expressions of hatred towards women.[36] However, [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baylor_University Baylor University] professor [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Gordon_Melton J. Gordon Melton] has written that Hubbard later disregarded and abrogated much of his earlier views about women, which Melton views as merely echoes of common prejudices at the time. Melton has also stated that the [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_Scientology Church of Scientology] welcomes both genders equally at all levels—from leadership positions to [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auditing_(Scientology) auditing] and so on—since Scientologists view people as [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thetan spiritual beings].[37]

นักปรัชญาและนักคิด (ศตวรรษที่ 17 - 20)

นักปรัชญาชาวตะวันตกหลายคนถูกกล่าวหาว่ามีความเกลียดชังผู้หญิง รวมทั้ง อาริสโตเติล, เรอเน เดการ์ต,โทมัส ฮอบส์, จอห์น ล็อก, เดวิด ฮูม, ฌ็อง-ฌัก รูโซ, G. W. F. Hegel, อาร์ทูร์ โชเพนเฮาเออร์, ฟรีดริช นีทเชอ, ชาลส์ ดาร์วิน, ซิกมุนด์ ฟรอยด์, Otto Weininger, Oswald Spengler, และ John Lucas.[3]

Aristotle

Aristotle believed women were inferior and described them as "deformed males".[38][39] In his work Politics, he states

as regards the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject 4 (1254b13-14).[39]

Another example is Cynthia's catalog where Cynthia states "Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity'.[38] Aristotle believed that men and women naturally differed both physically and mentally. He claimed that women are "more mischievous, less simple, more impulsive ... more compassionate[,] ... more easily moved to tears[,] ... more jealous, more querulous, more apt to scold and to strike[,] ... more prone to despondency and less hopeful[,] ... more void of shame or self-respect, more false of speech, more deceptive, of more retentive memory [and] ... also more wakeful; more shrinking [and] more difficult to rouse to action" than men.[40]

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Jacques_Rousseau Jean-Jacques Rousseau] is well known for his views against equal rights for women for example in his treatise [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emile,_or_On_Education Emile], he writes: "Always justify the burdens you impose upon girls but impose them anyway... . They must be thwarted from an early age... . They must be exercised to constraint, so that it costs them nothing to stifle all their fantasies to submit them to the will of others." Other quotes consist of "closed up in their houses", "must receive the decisions of fathers and husbands like that of the church".[41]

Charles Darwin

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Darwin Charles Darwin] wrote on the subject female inferiority through the lens of human evolution.[42] He noted in his book The Descent of Men: "young of both sexes resembled the adult female in most species" which he extrapolated and further reasoned "males were more evolutionarily advanced than females". Darwin believed all savages, children and women had smaller brains and therefore led more by instinct and less by reason.[42] Such ideas quickly spread to other scientists such as Professor Carl Vogt of natural sciences at the University of Geneva who argued "the child, the female, and the senile white" had the mental traits of a "grown up Negro", that the female is similar in intellectual capacity and personality traits to both infants and the "lower races" such as blacks while drawing conclusion that women are closely related to lower animals than men and "hence we should discover a greater apelike resemblance if we were to take a female as our standard".[42] Darwin's beliefs about women were also reflective of his attitudes towards women in general for example his views towards marriage as a young man in which he was quoted ""how should I manage all my business if obligated to go everyday walking with my wife – Ehau!" and that being married was "worse than being a Negro".[42] Or in other instances his concern of his son marrying a woman named Martineau about which he wrote "... he shall be not much better than her "nigger." Imagine poor Erasmus a nigger to so philosophical and energetic a lady ... Martineau had just returned from a whirlwind tour of America, and was full of married women's property rights ... Perfect equality of rights is part of her doctrine...We must pray for our poor "nigger.""[42]

Arthur Schopenhauer

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Schopenhauer Arthur Schopenhauer] has been noted as a misogynist by many such as the philosopher, critic, and author Tom Grimwood.[43] In a 2008 article Grimwood wrote published in the philosophical journal of Kritique, Grimwood argues that Schopenhauer's misogynistic works have largely escaped attention despite being more noticeable than those of other philosophers such as Nietzsche.[43] For example, he noted Schopenhauer's works where the latter had argued women only have "meagre" reason comparable that of "the animal" "who lives in the present". Other works he noted consisted of Schopenhauer's argument that women's only role in nature is to further the species through childbirth and hence is equipped with the power to seduce and "capture" men.[43] He goes on to state that women's cheerfulness is chaotic and disruptive which is why it is crucial to exercise obedience to those with rationality. For her to function beyond her rational subjugator is a threat against men as well as other women, he notes. Schopenhauer also thought women's cheerfulness is an expression of her lack of morality and incapability to understand abstract or objective meaning such as art.[43] This is followed up by his quote "have never been able to produce a single, really great, genuine and original achievement in the fine arts, or bring to anywhere into the world a work of permanent value".[43] Arthur Schopenhauer also blamed women for the fall of King Louis XIII and triggering the French Revolution, in which he was later quoted as saying:[43]

"At all events, a false position of the female sex, such as has its most acute symptom in our lady-business, is a fundamental defect of the state of society. Proceeding from the heart of this, it is bound to spread its noxious influence to all parts."[43]

Schopenhauer has also been accused of misogyny for his essay "On Women" (Über die Weiber), in which he expressed his opposition to what he called "Teutonico-Christian stupidity" on female affairs. He argued that women are "by nature meant to obey" as they are "childish, frivolous, and short sighted".[3] He claimed that no woman had ever produced great art or "any work of permanent value".[3] He also argued that women did not possess any real beauty:[44]

It is only a man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual impulse that could give the name of the fair sex to that under-sized, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race; for the whole beauty of the sex is bound up with this impulse. Instead of calling them beautiful there would be more warrant for describing women as the unaesthetic sex.

Nietzsche

In [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beyond_Good_and_Evil Beyond Good and Evil], [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Nietzsche Friedrich Nietzsche] stated that stricter controls on women was a condition of "every elevation of culture".[45] In his [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thus_Spoke_Zarathustra Thus Spoke Zarathustra], he has a female character say "You are going to women? Do not forget the whip!"[46] In [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twilight_of_the_Idols Twilight of the Idols], Nietzsche writes "Women are considered profound. Why? Because we never fathom their depths. But women aren't even shallow."[47] There is controversy over the questions of whether or not this amounts to misogyny, whether his polemic against women is meant to be taken literally, and the exact nature of his opinions of women.[48]

Hegel

[./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Wilhelm_Friedrich_Hegel Hegel's] view of women can be characterized as misogynistic.[49] Passages from Hegel's [./https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elements_of_the_Philosophy_of_Right Elements of the Philosophy of Right] illustrate the criticism:[50]

Women are capable of education, but they are not made for activities which demand a universal faculty such as the more advanced sciences, philosophy and certain forms of artistic production... Women regulate their actions not by the demands of universality, but by arbitrary inclinations and opinions.

Online misogyny

อ้างอิง

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Code, Lorraine (2000). Encyclopedia of Feminist Theories (1st ed.). London: Routledge. p. 346. ISBN 0-415-13274-6.

- ↑ Kramarae, Cheris (2000). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women. New York: Routledge. pp. 1374–1377. ISBN 0-415-92088-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Clack, Beverley (1999). Misogyny in the Western Philosophical Tradition: A Reader. New York: Routledge. pp. 95–241. ISBN 0-415-92182-1. อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่สมเหตุสมผล มีนิยามชื่อ "Clack1999" หลายครั้งด้วยเนื้อหาต่างกัน - ↑ Johnson, Allan G (2000). "The Blackwell dictionary of sociology: A user's guide to sociological language". ISBN 978-0-631-21681-0. สืบค้นเมื่อ November 21, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal ต้องการ|journal=(help), ("ideology" in all small capitals in original). - ↑ The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles (Oxford: Clarendon Press (Oxford Univ. Press), [4th] ed. 1993 (ISBN 0-19-861271-0)) (SOED) ("[h]atred of women").

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1992 (ISBN 0-395-44895-6)) ("[h]atred of women").

- ↑ Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged (G. & C. Merriam, 1966) ("a hatred of women").

- ↑ Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary (N.Y.: Random House, 2d ed. 2001 (ISBN 0-375-42566-7)).

- ↑ Roberts, J.W (2002-06-01). City of Sokrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens. ISBN 978-0-203-19479-9.

- ↑ The editio princeps is on page 255 of volume three of Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta (SVF, Old Stoic Fragments), see External links.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 A recent critical text with translation is in Appendix A to Will Deming, Paul on Marriage and Celibacy: The Hellenistic Background of 1 Corinthians 7, pp. 221–226. Misogunia appears in the accusative case on page 224 of Deming, as the fifth word in line 33 of his Greek text. It is split over lines 25–26 in von Arnim.

- ↑ 38-43, fr. 63, in von Arnim, J. (ed.). Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta. Vol. 3. Leipzig: Teubner, 1903.

- ↑ SVF 3:103. Misogyny is the first word on the page.

- ↑ Teun L. Tieleman, Chrysippus' on Affections: Reconstruction and Interpretations, (Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2003), p. 162. ISBN 90-04-12998-7

- ↑ Ricardo Salles, Metaphysics, Soul, and Ethics in Ancient Thought: Themes from the Work of Richard Sorabji, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005), 485.

- ↑ "Feminist History of Philosophy (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2013-10-01.

- ↑ Pappas, Nickolas (2003-09-09). Routledge philosophy guidebook to Plato and the Republic. ISBN 978-0-415-29996-1.

- ↑ Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon (LSJ), revised and augmented by Henry Stuart Jones and Roderick McKenzie, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940). ISBN 0-19-864226-1

- ↑ Strabo,Geography, Book 7 [Alexandria] Chapter 3.

- ↑ Menander, The Plays and Fragments, translated by Maurice Balme, contributor Peter Brown, Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-283983-7

- ↑ He is supported (or followed) by Theognostus the Grammarian's 9th century Canones, edited by John Antony Cramer, Anecdota Graeca e codd. manuscriptis bibliothecarum Oxoniensium, vol. 2, (Oxford University Press, 1835), p. 88.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Marcus Tullius Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, Book 4, Chapter 11.

- ↑ Holland, J: Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice, pp. 12–13. Avalon Publishing Group, 2006.

- ↑ "Sample Chapter for Faure, B.: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender". Press.princeton.edu. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2013-10-05. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2013-10-01.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|deadurl=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|url-status=) (help) - ↑ Rogers, Katharine M. The Troublesome Helpmate: A History of Misogyny in Literature, 1966.

- ↑ Ruthven, K. K (1990). Feminist literary studies: An introduction. ISBN 978-0-521-39852-7.

- ↑ "Galatians 3:28 – prooftext or context?". The council on biblical manhood and womanhood. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ February 6, 2015. สืบค้นเมื่อ January 6, 2015.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|deadurl=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|url-status=) (help) - ↑ Hove, Richard. Equality in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the Gender Dispute (Wheaton: Crossway, 1999), p. 17.

- ↑ Campbell, Ken M (October 1, 2003). Marriage and family in the biblical world. ISBN 978-0-8308-2737-4.

- ↑ Rinck, Margaret J. (1990). Christian Men Who Hate Women: Healing Hurting Relationships. Zondervan. pp. 81–85. ISBN 978-0-310-51751-1.

- ↑ Weigel, Christopher West ; with a foreword by George (2003). Theology of the body explained : a commentary on John Paul II's "Gospel of the body". Leominster, Herefordshire: Gracewing. ISBN 978-0-85244-600-3.

- ↑ "Verse 34 of Chapter 4 is an oft-cited Verse in the Qur'an used to demonstrate that Islam is structurally patriarchal, and thus Islam internalizes male dominance." Dahlia Eissa, "Constructing the Notion of Male Superiority over Women in Islam: The influence of sex and gender stereotyping in the interpretation of the Qur'an and the implications for a modernist exegesis of rights", Occasional Paper 11 in Occasional Papers (Empowerment International, 1999).

- ↑ Hashmi, Taj. Popular Islam and Misogyny: A Case Study of Bangladesh. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Nomani, Asra Q. (October 22, 2006). "Clothes Aren't the Issue". Washington Post.

- ↑ Julie A. Webber (2004). Expanding curriculum theory: dis/positions and lines of flight. Psychology Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8058-4665-2.

- ↑ Scherstuhl, Alan (June 21, 2010). "The Church of Scientology does not want you to see L. Ron Hubbard's woman-hatin' book chapter". The Village Voice. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ June 25, 2010.

{{cite news}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|deadurl=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|url-status=) (help) - ↑ "Gender and Sexuality". Patheos.com. 2012-07-26. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2013-10-01.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Witt, Charlotte; Shapiro, Lisa (2016-01-01). Zalta, Edward N. (บ.ก.). Feminist History of Philosophy (Spring 2016 ed.).

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Smith, Nicholas D. (1983). "Plato and Aristotle on the Nature of Women". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 21 (4): 467–478. doi:10.1353/hph.1983.0090.

- ↑ History of Animals, 608b. 1–14

- ↑ Blum, C. (2010). "Rousseau and Feminist Revision". Eighteenth-Century Life. 34 (3): 51–54. doi:10.1215/00982601-2010-012.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 Bergman, Gerald (2002-12-01). "The history of the human female inferiority ideas in evolutionary biology". Rivista di Biologia. 95 (3): 379–412. ISSN 0035-6050. PMID 12680306.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 43.5 43.6 Grimwood, Tom (2008-01-01). "The Limits of Misogyny: Schopenhauer, "On Women"". Kritike: An Online Journal of Philosophy. 2 (2): 131–145. doi:10.3860/krit.v2i2.854.

- ↑ Durant, Will (1983). The Story of Philosophy. New York, N.Y.: Simon and Schuster. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-671-20159-3.

- ↑ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1886). Beyond Good and Evil. Germany. สืบค้นเมื่อ January 23, 2014.

- ↑ Burgard, Peter J. (May 1994). Nietzsche and the Feminine. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8139-1495-4.

- ↑ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1889). Twilight of the Idols. Germany. ISBN 978-0-14-044514-5. สืบค้นเมื่อ January 23, 2014.

- ↑ Robert C. Holub, Nietzsche and The Women's Question. Coursework for Berkley University.

- ↑ Gallagher, Shaun (1997). Hegel, history, and interpretation. SUNY Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-7914-3381-2.

- ↑ Alanen, Lilli; Witt, Charlotte (2004). Feminist Reflections on the History of Philosophy. ISBN 978-1-4020-2488-7.

บรรณานุกรม

- Boteach, Shmuley. Hating Women: America's Hostile Campaign Against the Fairer Sex. 2005.

- Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975.

- Clack, Beverley, comp. Misogyny in the Western Philosophical Tradition: a reader. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1999.

- Dijkstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Chodorow, Nancy. The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, 1978.

- Dworkin, Andrea. Woman Hating. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1974.

- Ellmann, Mary. Thinking About Women. 1968.

- Ferguson, Frances and R. Howard Bloch. Misogyny, Misandry, and Misanthropy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-520-06544-4

- Forward, Susan, and Joan Torres. Men Who Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them: When Loving Hurts and You Don't Know Why. Bantam Books, 1986. ISBN 0-553-28037-6

- Gilmore, David D. Misogyny: the Male Malady. 2001.

- Haskell, Molly. From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. 1974. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Holland, Jack. Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice. 2006.

- Kipnis, Laura. The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability. 2006. ISBN 0-375-42417-2

- Klein, Melanie. The Collected Writings of Melanie Klein. 4 volumes. London: Hogarth Press, 1975.

- Marshall, Gordon. 'Misogyny'. In Oxford Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Johnson, Allan G. 'Misogyny'. In Blackwell Dictionary of Sociology: A User's Guide to Sociological Language. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2000.

- Millett, Kate. Sexual Politics. New York: Doubleday, 1970.

- Morgan, Fidelis. A Misogynist's Source Book.

- Patai, Daphne, and Noretta Koertge. Professing Feminism: Cautionary Tales from the Strange World of Women's Studies. 1995. ISBN 0-465-09827-4

- Penelope, Julia. Speaking Freely: Unlearning the Lies of our Fathers' Tongues. Toronto: Pergamon Press Canada, 1990.

- Rogers, Katharine M. The Troublesome Helpmate: A History of Misogyny in Literature. 1966.

- Smith, Joan. Misogynies. 1989. Revised 1993.

- Tumanov, Vladimir. "Mary versus Eve: Paternal Uncertainty and the Christian View of Women." Neophilologus 95 (4) 2011: 507-521.

- von Arnim, J. (ed.). Stoicorum veterum fragmenta Vol. 3. Leipzig: Teubner, 1903.

- World Health Organization Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women* 2005.