ผลต่างระหว่างรุ่นของ "ไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน"

| บรรทัด 71: | บรรทัด 71: | ||

=== ทั่วโลก === |

=== ทั่วโลก === |

||

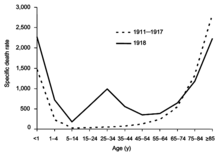

[[ไฟล์:W curve.png|thumb|upright=1|ความแตกต่างระหว่างอัตราการตายของไข้หวัดใหญ่ตามช่วงอายุ ของการระบาดทั่วปี 1918 และการระบาดตามปกติ - เสียชีวิตต่อ 100,000 คนในแต่ละกลุ่มอายุ, สหรัฐอเมริกา, ในช่วงก่อนการระบาดใหญ่ปี 1911–1917 (เส้นประ) และการระบาดทั่วปี 1918 (เส้นทึบ){{sfn|Taubenberger|Morens|2006|pp=15–22}}]] |

|||

<!--[[ไฟล์:W curve.png|thumb|upright=1|The difference between the influenza mortality age-distributions of the 1918 epidemic and normal epidemics – deaths per 100,000 persons in each age group, United States, for the interpandemic years 1911–1917 (dashed line) and the pandemic year 1918 (solid line){{sfn|Taubenberger|Morens|2006|pp=15–22}}]] |

|||

[[ไฟล์:1918 spanish flu waves.gif|thumb|upright=1| |

[[ไฟล์:1918 spanish flu waves.gif|thumb|upright=1|ภาวะระบาดทั่วสามระลอก: อัตราการตายของไข้หว้ดใหญ่และปอดบวมรายสัปดาห์, สหราชอาณาจักร, 1918–1919{{sfn|CDC|2009}}]] |

||

มีผู้ติดเชื้อไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนประมาณ 500 ล้านคนทั่วโลก หรือประมาณหนึ่งในสามของประชากรโลก{{sfn|Taubenberger|Morens|2006}} ในการประเมินจำนวนผู้เสียชีวิตมีความแตกต่างกันเป็นอย่างมาก ไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนได้รับการพิจารณาว่าเป็นหนึ่งในโรคระบาดร้ายแรงที่มีผู้เสียชีวิตมากสุดในประวัติศาสตร์<ref>{{cite journal |url= https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/232955/WER8049_50_428-431.PDF |title=Ten things you need to know about pandemic influenza (update of 14 October 2005). |journal=Weekly Epidemiological Record (Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire) |date=9 December 2005 |volume=80 |issue=49–50 |pages=428–431 |pmid=16372665}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Jilani |first1=TN |last2=Jamil |first2=RT |last3=Siddiqui |first3=AH |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513241/ |title=H1N1 Influenza (Swine Flu) |date=14 December 2019 |pmid=30020613 |work=[[National Center for Biotechnology Information|NCBI]] |access-date=11 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200312134634/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513241/ |archive-date=12 March 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

การประมาณการในปี 1991 ระบุว่าไวรัสฆ่าคนไประหว่าง 25 และ 39 ล้านคน{{sfn|Patterson|Pyle|1991}} การประมาณการปี 2005 ระบุจำนวนผู้เสียชีวิตที่ 50 ล้านคน (ประมาณน้อยกว่า 3% ของประชากรโลก) และอาจสูงถึง 100 ล้านคน (มากกว่า 5%){{sfn|Knobler|2005}}{{sfn|Johnson|Mueller|2002}} อย่างไรก็ตาม มีการประเมินใหม่ในปี 2018 คาดว่าจะมีผู้เสียชีวิตจำนวนประมาณ 17 ล้านคน<ref name=Spreeuwenberg>{{cite journal |last1=P. Spreeuwenberg |display-authors=etal|title=Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. |journal=[[American Journal of Epidemiology]] |volume=187|issue=12|pages=2561–2567|date=1 December 2018 |doi=10.1093/aje/kwy191 |pmid=30202996}}</ref> แม้ว่าจะมีการโต้แย้งกันก็ตาม<ref>{{cite journal |first1=Siddharth |last1=Chandra |first2=Julia |last2=Christensen |title=Re: "reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic" |journal=Am. J. Epid. |volume=188 |issue=7 |pages=1404–1406 |date=2 March 2019 |doi=10.1093/aje/kwz044|pmid=30824934 }} and response {{cite journal |first1=Peter |last1=Spreeuwenberg |first2=Madelon |last2=Kroneman |first3=John |last3=Paget |url=https://postprint.nivel.nl/PPpp7146.pdf |title=The Authors Reply |journal=Am. J. Epid. |volume=188 |issue=7 |pages=1405–1406 |date=2 March 2019 |doi=10.1093/aje/kwz041 |pmid=30824908 |access-date=12 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200312204122/https://postprint.nivel.nl/PPpp7146.pdf |archive-date=12 March 2020 |url-status=live }}</ref> ในเวลานั้นมีประชากรโลกประมาณ 1.8 ถึง 1.9 พันล้านคน<ref>{{cite web |title=Historical Estimates of World Population |url=https://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_history.php |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120709092946/https://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/table_history.php |url-status=dead |archive-date=9 July 2012 |access-date=29 March 2013}}</ref> ประมาณการเหล่านี้ มีความสอดคล้องกันคืออยู่ระหว่าง 1 และ 6 เปอร์เซ็นต์ของจำนวนประชากร |

|||

ไข้หวัดใหญ่สายพันธุ์นี้คร่าชีวิตผู้คนใน 24 สัปดาห์ได้มากกว่า [[เอดส์|HIV/AIDS]] ในระยะเวลา 24 ปี{{sfn|Barry| 2004}} อย่างไรก็ตาม อัตราการตายต่อจำนวนประชากรยังน้อยกว่า[[กาฬมรณะ]]ซึ่งระบาดเป็นเวลาหลายร้อยปี<ref name="'Human Extinction Isn't That Unlikely,' The Atlantic, Robinson Meyer, April 29, 2016">{{cite magazine |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/04/a-human-extinction-isnt-that-unlikely/480444/ |title=Human extinction isn't that unlikely |magazine=The Atlantic |author=Robinson Meyer |date=29 April 2016 |access-date=6 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160501051000/http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/04/a-human-extinction-isnt-that-unlikely/480444/ |archive-date=1 May 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The disease killed in many parts of the world. Some 12-17 million people died [[1918 flu pandemic in India|in India]], about 5% of the population.<ref>{{Cite journal |pmc = 1118673|year = 2000|last1 = Mayor|first1 = S.|title = Flu experts warn of need for pandemic plans|journal = British Medical Journal|volume = 321|issue = 7265|pages = 852|pmid = 11021855|doi = 10.1136/bmj.321.7265.852}}</ref> The death toll in [[British Raj|India's British-ruled districts]] was 13.88 million.{{sfn|Chandra|Kuljanin|Wray|2012}} Arnold (2019) estimates at least 12 million dead.<ref>David Arnold, "Dearth and the Modern Empire: The 1918–19 Influenza Epidemic in India," ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' 29 (2019): 181-200. </ref> |

<!--The disease killed in many parts of the world. Some 12-17 million people died [[1918 flu pandemic in India|in India]], about 5% of the population.<ref>{{Cite journal |pmc = 1118673|year = 2000|last1 = Mayor|first1 = S.|title = Flu experts warn of need for pandemic plans|journal = British Medical Journal|volume = 321|issue = 7265|pages = 852|pmid = 11021855|doi = 10.1136/bmj.321.7265.852}}</ref> The death toll in [[British Raj|India's British-ruled districts]] was 13.88 million.{{sfn|Chandra|Kuljanin|Wray|2012}} Arnold (2019) estimates at least 12 million dead.<ref>David Arnold, "Dearth and the Modern Empire: The 1918–19 Influenza Epidemic in India," ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'' 29 (2019): 181-200. </ref> |

||

Estimates for the death toll in China have varied widely,<ref name="ijima">{{cite book|author=Iijima, W.|title=The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918: New Perspectives|publisher=Routledge|year=2003|editor1=Phillips, H.|location=London and New York|pages=101–109|article=Spanish influenza in China, 1918–1920: a preliminary probe|editor2=Killingray, D.}}</ref>{{sfn|Patterson|Pyle|1991}} a range which reflects the lack of centralised collection of health data at the time due to the [[Warlord Era|Warlord period]]. The first estimate of the Chinese death toll was made in 1991 by Patterson and Pyle, which estimated China had a death toll of between 5 and 9 million. However, this 1991 study was later criticized by later studies due to flawed methodology, and newer studies have published estimates of a far lower mortality rate in China.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|last=Killingray|first=David|url=https://books.google.com/?id=k79_8QX8n44C&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Spanish+Influenza+Pandemic+of+1918-1919:+New+Perspectives#v=onepage&q=local%20statistical%20data&f=false|title=The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919: New Perspectives|last2=Phillips|first2=Howard|year=2003|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-56640-2|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Iijima|first=Wataru|url=|title=The Spanish influenza in China, 1918–1920|date=1998|publisher=|isbn=|editor-last=|location=|pages=|language=English|oclc=46987588}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Langford|first=Christopher|date=2005|title=Did the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?|journal=Population and Development Review|language=en|volume=31|issue=3|pages=473–505|doi=10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x|issn=1728-4457}}</ref> For instance, Iijima in 1998 estimates the death toll in China to be between 1 and 1.28 million based on data available from Chinese port-cities.<ref>{{Cite conference |conference=Spanish 'Flu 1918-1998: Reflections on the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 after 80 Years |location=Cape Town, South Africa |last=Iijima|first=Wataru|date=1998|title=The Spanish influenza in China, 1918-1920|url=https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/5409238}}</ref> As Wataru Iijima notes,<blockquote>"Patterson and Pyle in their study 'The 1918 Influenza Pandemic' tried to estimate the number of deaths by Spanish influenza in China as a whole. They argued that between 4.0 and 9.5 million people died in China, but this total was based purely on the assumption that the death rate there was 1.0–2.25 per cent in 1918, because China was a poor country similar to Indonesia and India where the mortality rate was of that order. Clearly their study was not based on any local Chinese statistical data."<ref>{{Cite book|last=Killingray|first=David|url=https://books.google.com/?id=k79_8QX8n44C&pg=PT139&lpg=PT139&dq=%22Patterson+and+Pyle+in+their+study+'The+1918+Influenza+Pandemic'+tried+to+estimate+the+number+of+deaths+by+Spanish+influenza+in+China+as+a+whole.+They+argued+that+between+4.0+and+9.5+million+people+died+in+China,+but+this+total+was+based+purely+on+the+assumption+that+the+death+rate+there+was+1.0-2.25+per+cent+in+1918,+because+China+was+a+poor+country+similar+to+Indonesia+and+India+where+the+mortality+rate+was+of+that+order.+Clearly+their+study+was+not+based+on+any+local+Chinese+statistical+data.%22#v=onepage&q=%22Patterson%20and%20Pyle%20in%20their%20study%20'The%201918%20Influenza%20Pandemic'%20tried%20to%20estimate%20the%20number%20of%20deaths%20by%20Spanish%20influenza%20in%20China%20as%20a%20whole.%20They%20argued%20that%20between%204.0%20and%209.5%20million%20people%20died%20in%20China,%20but%20this%20total%20was%20based%20purely%20on%20the%20assumption%20that%20the%20death%20rate%20there%20was%201.0-2.25%20per%20cent%20in%201918,%20because%20China%20was%20a%20poor%20country%20similar%20to%20Indonesia%20and%20India%20where%20the%20mortality%20rate%20was%20of%20that%20order.%20Clearly%20their%20study%20was%20not%20based%20on%20any%20local%20Chinese%20statistical%20data.%22&f=false|title=The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919: New Perspectives|last2=Phillips|first2=Howard|date=2003|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-56640-2|language=en}}</ref> </blockquote>The lower estimates of the Chinese death toll are based on the low mortality rates that were found in Chinese port-cities (for example, Hong Kong) and on the assumption that poor communications prevented the flu from penetrating the interior of China.<ref name="ijima" /> However, some contemporary newspaper and post office reports, as well as reports from missionary doctors, suggest that the flu did penetrate the Chinese interior and that influenza was bad in some locations in the countryside of China.<ref name="palerider">{{Cite book|last=Spinney|first=Laura|title=Pale rider – The Spanish flu of 1918 and how it changed the world|year=2017|isbn=978-1-910702-37-6|pages=167–169|author-link=Laura Spinney}}</ref> |

Estimates for the death toll in China have varied widely,<ref name="ijima">{{cite book|author=Iijima, W.|title=The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918: New Perspectives|publisher=Routledge|year=2003|editor1=Phillips, H.|location=London and New York|pages=101–109|article=Spanish influenza in China, 1918–1920: a preliminary probe|editor2=Killingray, D.}}</ref>{{sfn|Patterson|Pyle|1991}} a range which reflects the lack of centralised collection of health data at the time due to the [[Warlord Era|Warlord period]]. The first estimate of the Chinese death toll was made in 1991 by Patterson and Pyle, which estimated China had a death toll of between 5 and 9 million. However, this 1991 study was later criticized by later studies due to flawed methodology, and newer studies have published estimates of a far lower mortality rate in China.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|last=Killingray|first=David|url=https://books.google.com/?id=k79_8QX8n44C&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Spanish+Influenza+Pandemic+of+1918-1919:+New+Perspectives#v=onepage&q=local%20statistical%20data&f=false|title=The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919: New Perspectives|last2=Phillips|first2=Howard|year=2003|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-56640-2|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Iijima|first=Wataru|url=|title=The Spanish influenza in China, 1918–1920|date=1998|publisher=|isbn=|editor-last=|location=|pages=|language=English|oclc=46987588}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Langford|first=Christopher|date=2005|title=Did the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?|journal=Population and Development Review|language=en|volume=31|issue=3|pages=473–505|doi=10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x|issn=1728-4457}}</ref> For instance, Iijima in 1998 estimates the death toll in China to be between 1 and 1.28 million based on data available from Chinese port-cities.<ref>{{Cite conference |conference=Spanish 'Flu 1918-1998: Reflections on the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 after 80 Years |location=Cape Town, South Africa |last=Iijima|first=Wataru|date=1998|title=The Spanish influenza in China, 1918-1920|url=https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/5409238}}</ref> As Wataru Iijima notes,<blockquote>"Patterson and Pyle in their study 'The 1918 Influenza Pandemic' tried to estimate the number of deaths by Spanish influenza in China as a whole. They argued that between 4.0 and 9.5 million people died in China, but this total was based purely on the assumption that the death rate there was 1.0–2.25 per cent in 1918, because China was a poor country similar to Indonesia and India where the mortality rate was of that order. Clearly their study was not based on any local Chinese statistical data."<ref>{{Cite book|last=Killingray|first=David|url=https://books.google.com/?id=k79_8QX8n44C&pg=PT139&lpg=PT139&dq=%22Patterson+and+Pyle+in+their+study+'The+1918+Influenza+Pandemic'+tried+to+estimate+the+number+of+deaths+by+Spanish+influenza+in+China+as+a+whole.+They+argued+that+between+4.0+and+9.5+million+people+died+in+China,+but+this+total+was+based+purely+on+the+assumption+that+the+death+rate+there+was+1.0-2.25+per+cent+in+1918,+because+China+was+a+poor+country+similar+to+Indonesia+and+India+where+the+mortality+rate+was+of+that+order.+Clearly+their+study+was+not+based+on+any+local+Chinese+statistical+data.%22#v=onepage&q=%22Patterson%20and%20Pyle%20in%20their%20study%20'The%201918%20Influenza%20Pandemic'%20tried%20to%20estimate%20the%20number%20of%20deaths%20by%20Spanish%20influenza%20in%20China%20as%20a%20whole.%20They%20argued%20that%20between%204.0%20and%209.5%20million%20people%20died%20in%20China,%20but%20this%20total%20was%20based%20purely%20on%20the%20assumption%20that%20the%20death%20rate%20there%20was%201.0-2.25%20per%20cent%20in%201918,%20because%20China%20was%20a%20poor%20country%20similar%20to%20Indonesia%20and%20India%20where%20the%20mortality%20rate%20was%20of%20that%20order.%20Clearly%20their%20study%20was%20not%20based%20on%20any%20local%20Chinese%20statistical%20data.%22&f=false|title=The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919: New Perspectives|last2=Phillips|first2=Howard|date=2003|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-56640-2|language=en}}</ref> </blockquote>The lower estimates of the Chinese death toll are based on the low mortality rates that were found in Chinese port-cities (for example, Hong Kong) and on the assumption that poor communications prevented the flu from penetrating the interior of China.<ref name="ijima" /> However, some contemporary newspaper and post office reports, as well as reports from missionary doctors, suggest that the flu did penetrate the Chinese interior and that influenza was bad in some locations in the countryside of China.<ref name="palerider">{{Cite book|last=Spinney|first=Laura|title=Pale rider – The Spanish flu of 1918 and how it changed the world|year=2017|isbn=978-1-910702-37-6|pages=167–169|author-link=Laura Spinney}}</ref> |

||

รุ่นแก้ไขเมื่อ 19:38, 9 พฤษภาคม 2563

| ไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน | |

|---|---|

| |

| โรค | ไข้หวัดใหญ่ |

| สถานที่ | ทั่วโลก |

| รายงานผู้ป่วยรายแรก | สหรัฐ |

| วันที่ | มกราคม ค.ศ. 1918 – ธันวาคม ค.ศ. 1920 |

| ผู้ป่วยยืนยันสะสม | ประมาณ 500 ล้านคน[1] |

| เสียชีวิต | ประมาณ 17–50 ล้านคน |

การระบาดทั่วของไข้หวัดใหญ่ ค.ศ. 1918 (มกราคม ค.ศ. 1918 – ธันวาคม ค.ศ. 1920 หรือคำรู้จักว่าไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน) เป็นการระบาดทั่วของไข้หวัดใหญ่ที่มีผู้เสียชีวิตมากผิดปกติ โดยเป็นโรคระบาดทั่วครั้งแรกจากสองครั้งที่เกี่ยวข้องกับไวรัสไข้หวัดใหญ่เอช1เอ็น1[2] มีผู้ได้รับผลกระทบ 500 ล้านคนทั่วโลก ซึ่งรวมหมู่เกาะแปซิฟิกห่างไกลและอาร์กติก ทำให้มีผู้เสียชีวิต 40 ล้านคน ทำให้เป็นภัยพิบัติธรรมชาติที่มีผู้เสียชีวิตมากที่สุดครั้งหนึ่งในประวัติศาสตร์มนุษยชาติ[1][3][4][5]

การระบาดของไข้หวัดใหญ่ส่วนมากทำให้เยาวชน ผู้สูงอายุและผู้ป่วยที่อ่อนแออยู่แล้วเสียชีวิตมากกว่ากลุ่มอื่น ในทางตรงข้าม การระบาดทั่ว ค.ศ. 1918 จะทำให้ผู้ใหญ่ตอนต้นที่เดิมสุขภาพดีเสียชีวิตมาก การวิจัยสมัยใหม่โดยใช้ไวรัสที่นำมาจากศพของผู้เสียชีวิตที่ถูกแช่แข็ง สรุปว่าไวรัสทำให้เสียชีวิตได้จากไซโทไคน์สตอร์ม (คือ ปฏิกิริยามากเกินของระบบภูมิคุ้มกันร่างกาย) ปฏิกิริยาภูมิคุ้มกันที่แข็งแรงของผู้ใหญ่ตอนต้นทำร้ายร่างกาย ขณะที่ระบบภูมิคุ้มกันที่อ่อนแอกว่าของเด็กและผู้ใหญ่วัยกลางคนทำให้มีผู้เสียชีวิตน้อยกว่าในกลุ่มเหล่านี้[6]

ข้อมูลประวัติศาสตร์และวิทยาการระบาดไม่เพียงพอระบุแหล่งกำเนิดทางภูมิศาสตร์ของการระบาดทั่วนี้[1] การระบาดนี้เกี่ยวพันในการระบาดของเอ็นเซฟาไลติส ลีทาร์จิกา (encephalitis lethargica) ในคริสต์ทศวรรษ 1920[7]

นิรุกติศาสตร์

ถึงอย่างไรก็ตาม แม้จะมีชื่อไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน แต่ข้อมูลทางประวัติศาสตร์และการระบาดวิทยาไม่สามารถระบุแหล่งกำเนิดทางภูมิศาสตร์ของไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนได้[1] ที่มาของชื่อ "สเปนไข้ใหญ่หวัด" เกิดจากการแพร่ระบาดของโรคระบาดจากฝรั่งเศสไปยังสเปนในเดือนพฤศจิกายน 1918[8][9] ในเวลานั้นสเปนไม่ได้เข้าร่วมสงครามยังคงเป็นกลางไว้ และไม่เคยมีการตรวจพิจารณาสื่อในช่วงสงคราม[10][11] หนังสือพิมพ์จึงมีอิสระที่จะรายงานผลกระทบของโรคระบาด เช่น กษัตริย์อัลฟองโซที่สิบสามป่วยหนัก และเรื่องราวการระบาดอย่างกว้างขวาง ข่าวเหล่านี้สร้างความประทับใจเทียมในสเปนโดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งเมื่อเกิดผลกระทบอย่างรุนแรง[12]

เกือบหนึ่งศตวรรษหลังจากไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนระบาดในปี 1918–1920 องค์การอนามัยโลก (WHO) เรียกร้องให้นักวิทยาศาสตร์ หน่วยงานระดับชาติ และสื่อต่างๆปฏิบัติตามแนวปฏิบัติที่ดีในการตั้งชื่อโรคติดเชื้อในมนุษย์ชนิดใหม่ เพื่อลดผลกระทบเชิงลบต่อประเทศชาติ เศรษฐกิจ และผู้คน[13][14] คำศัพท์สมัยใหม่ที่ใช้เรียกไวรัสนี้ ได้แก่ "การระบาดทั่วของโรคไข้หวัดใหญ่ปี 1918 (1918 influenza pandemic, 1918 flu pandemic)" หรือในรูปแบบต่างๆ[15][16][17]

ประวัติ

สมมติฐานเกี่ยวกับแหล่งที่มา

สหราชอาณาจักร

ทฤษฎีของนักวิจัยหลายคนเชื่อว่ากองทหารสหราชอาณาจักรและโรงพยาบาลสนามในเมืองเอตาปล์ (Étaples) ในฝรั่งเศสเป็นจุดกำเนิดของไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน ทีมนักวิจัยอังกฤษนำโดยจอห์น ออกซ์ฟอร์ด (John Oxford) นักวิทยาไวรัสได้ตีพิมพ์ในปี ค.ศ. 1999[18] ในปลายปี ค.ศ. 1917 นักพยาธิวิทยากองทัพรายงานว่ามีโรคใหม่ที่มีอัตราการตายสูงซึ่งต่อมาพวกเขาได้ยืนยันว่าเป็นไข้หวัดใหญ่ ค่ายและโรงพยาบาลที่แออัดเป็นสถานที่ที่เหมาะสำหรับการแพร่กระจายของไวรัสระบบทางเดินหายใจ โรงพยาบาลรักษาผู้ได้รับบาดเจ็บจากการโจมตีด้วยเคมีและจากการโจมตีอื่นๆในสงครามนับพันราย และมีทหารกว่า 100,000 คนผ่านค่ายทุกวัน นอกจากนี้ ยังเป็นบ้านของหมูและสัตว์ปีกซึ่งถูกซื้อเข้ามาเป็นประจำเพื่อเป็นเสบียงอาหารจากหมู่บ้านโดยรอบ ออกซ์ฟอร์ดและทีมของเขาตั้งสมมติฐานว่าไวรัสมีต้นกำเนิดจากนก เกิดการกลายพันธุ์และแพร่ไปยังสุกรที่อาศัยอยู่ใกล้กัน[19][20]

รายงานที่ตีพิมพ์ในปี ค.ศ. 2016 ในวารสารสมาคมการแพทย์จีน (Chinese Medical Association) พบหลักฐานว่า 1918 ไวรัส มีการแพร่กระจายในกองทัพยุโรปเป็นเวลาหลายเดือนและอาจเป็นปีก่อนที่จะมีการระบาดใหญ่ในปี ค.ศ. 1981[21]

ประเทศสหรัฐอเมริกา

ในปี ค.ศ. 2018 การศึกษาสไลด์เนื้อเยื่อและรายงานทางการแพทย์ที่นำโดยศาสตราจารย์ด้านชีววิทยาวิวัฒนาการ ไมเคิล โวโรเบย์ (Michael Worobey) พบว่ามีหลักฐานการเกิดโรคจากแคนซัส เนื่องจากมีผู้ป่วยและมีผู้เสียชีวิตน้อยเมื่อเทียบกับสถานการณ์ในนิวยอร์กซิตี้ในช่วงเวลาเดียวกัน จากการศึกษาผ่านวงศ์วานวิวัฒนาการยังพบหลักฐานว่าเชื้อไวรัสน่าจะมีต้นกำเนิดในอเมริกาเหนือแม้ว่าจะไม่ได้ข้อสรุป นอกจากนี้ ฮีแมกกูตินิน ไกลโคโปรตีน (haemagglutinin glycoproteins) ของไวรัสแสดงว่ามันเกิดและอยู่ไกลไปก่อนปี ค.ศ. 1918 และการศึกษาอื่น ๆ ชี้ให้เห็นว่าการรวมตัวของยีนส์ของไวรัส H1N1 มีแนวโน้มที่จะเกิดขึ้นราว ๆ ปี ค.ศ. 1915[22]

ประเทศจีน

หนึ่งในไม่กี่ภูมิภาคของโลกที่ดูเหมือนจะได้รับผลกระทบเพียงเล็กน้อยจากการระบาดของไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนในปี ค.ศ. 1918 คือสาธารณรัฐจีน ซึ่งอาจจะมีไข้หวัดใหญ่ฤดูเล็กน้อยในปี ค.ศ. 1918 (แม้ว่าจะมีการโต้แย้งเนื่องจากขาดข้อมูลในช่วงยุคสมัยขุนศึกของจีน) ในการศึกษาหลายชิ้นมีเอกสารที่แสดงว่ามีผู้เสียชีวิตจากไข้หวัดใหญ่ในจีนค่อนข้างน้อยเมื่อเทียบกับภูมิภาคอื่น ๆ ของโลก[23][24][25] สิ่งนี้นำไปสู่การคาดการณ์ว่าไข้หวัดใหญ่ที่ระบาดในปี ค.ศ. 1918 มีต้นกำเนิดในประเทศจีน[26][24][27][28] โดยความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างผู้ป่วยไข้หวัดใหญ่ฤดูที่น้อยและอัตราการตายจากไข้หวัดใหญ่ในประเทศจีนที่ต่ำในปี ค.ศ. 1918 อาจจะอธิบายได้ว่าประชากรชาวจีนมีระบบภูมิคุ้มกันแบบจำเพาะไวรัสไข้หวัดใหญ่แล้ว[29][26][24]

ในปี ค.ศ. 1993 โคลด แฮนนาว (Claude Hannoun) ผู้เชี่ยวชาญชั้นนำเกี่ยวกับไข้หวัดใหญ่ 1918 สถาบันปาสเตอร์ ยืนยันว่าไวรัสรูปแรกน่าจะมาจากประเทศจีนจากนั้นก็กลายพันธุ์ในสหรัฐอเมริกาใกล้กับบอสตันและจากที่นั่นแพร่กระจายไปยังแบร็สต์ ฝรั่งเศส สมรภูมิยุโรป และทั่วโลกโดยมีทหารและลูกเรือฝ่ายสัมพันธมิตรเป็นผู้แพร่[30]

ในปี ค.ศ. 2014 นักประวัติศาสตร์สังกัดมหาวิทยาลัยเมมฌมเรียลแห่งนิวฟันด์แลนด์ (Memorial University of Newfoundland) ในเซนต์จอนส์ มาร์ค ฮัมฟรีส์ (Mark Humphries) โต้แย้งว่าการระดมกลุ่มผู้ใช้แรงงานชาวจีนราว 96,000 คน เพื่อทำงานเบื้องหลังแนวรบอังกฤษและฝรั่งเศสอาจเป็นแหล่งที่มาของการระบาด ตามข้อสรุปของเขาในบันทึกที่เพิ่งเปิดเผย เขาพบหลักฐานจดหมายเหตุที่แสดงว่าโรคทางเดินหายใจเกิดขึ้นในภาคเหนือของจีนในเดือนพฤศจิกายน ค.ศ. 1917 ถูกระบุในปีถัดไปโดยเจ้าหน้าที่สาธารณสุขจีนว่าเป็นไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน[31][32]

รายงานที่ตีพิมพ์ในปี ค.ศ. 2016 ในวารสารสมาคมการแพทย์จีน (Chinese Medical Association) ไม่พบหลักฐานว่าเชื้อ 1918 ไวรัสถูกนำเข้าสู่ยุโรปผ่านทหารและคนงานจีนและคนเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ และพบหลักฐานการหมุนเวียนของไวรัสในยุโรปก่อนการระบาดแทน[21] การศึกษาปี ค.ศ. 2016 ชี้ให้เห็นว่าอัตราการตายจากไข้หวัดใหญ่ที่พบในคนงานจีนและเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ในยุโรปต่ำ (ประมาณ 1/1000) หมายความว่าการระบาดของโรคไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนในปี ค.ศ. 1918 นั้นไม่ได้เกิดจากคนงานเหล่านั้น[21]

การศึกษาในปี ค.ศ. 2018 ของสไลด์เนื้อเยื่อและรายงานทางการแพทย์นำโดยศาสตราจารย์ด้านชีววิทยาวิวัฒนาการ ไมเคิล โวโรเบย์ (Michael Worobey) พบหลักฐานแย้งที่ว่าโรคนี้แพร่กระจายโดยคนงานชาวจีน โดยสังเกตว่าคนงานที่เข้าสู่ยุโรปผ่านเส้นทางอื่น ๆ ไม่ส่งผลให้เกิดการแพร่กระจายของโรค ทำให้พวกเขาไม่ใช่เจ้าบ้าน (host) ต้นกำเนิด[22]

อื่นๆ

แฮนนาวพิจารณาสมมติฐานทางเลือกของแหล่งกำเนิด เช่น สเปน, แคนซัส, และแบร็สต์ ซึ่งอาจเป็นไปได้หรือไม่ก็ได้[30] นักวิทยาศาสตร์นโยบาย แอนดรู ไพรซ์ - สมิธ (Andrew Price-Smith) เผยแพร่ข้อมูลจาก หอจดหมายเหตุของออสเตรียที่แสดงว่าไข้หวัดใหญ่เริ่มในประเทศออสเตรียเมื่อต้นปี ค.ศ. 1917[33]

การระบาด

เมื่อผู้ติดเชื้อจามหรือไออนุภาคไวรัสมากกว่าครึ่งล้านอนุภาคสามารถแพร่กระจายไปยังบุคคลที่อยู่ใกล้เคียง[34] ค่ายทหารที่หนาแน่นและการเคลื่อนย้ายทหารจำนวนมากในสงครามโลกครั้งที่หนึ่งเป็นตัวเร่งให้เกิดการระบาดและเพิ่มอัตราการตาย สงครามได้เพิ่มความร้ายแรงของพลังทำลายของไวรัส มีการคาดการณ์ว่าระบบภูมิคุ้มกันโรคของทหารอ่อนแอลงเนื่องจากการขาดสารอาหาร ความเครียดจากการต่อสู้ และการโจมตีทางเคมี[35][36]

ปัจจัยหลักในการเกิดการระบาดของโรคไข้หวัดใหญ่ทั่วโลกนี้คือการเดินทางที่เพิ่มขึ้น ระบบการขนส่งสมัยใหม่ทำให้ทหาร กะลาสีและพลเรือนเดินทางได้ง่ายขึ้นและแพร่กระจายโรคได้ง่ายขึ้นด้วยเช่นกัน[37] อีกประการหนึ่ง คือการโกหกและการปฏิเสธจากรัฐบาลทำให้ประชากรไม่พร้อมที่จะรับมือกับการระบาด[38]

ในสหรัฐอเมริกา โรคนี้ถูกเฝ้าระวังเป็นครั้งแรกในแฮสเค็ลล์เคาท์ตี รัฐแคนซัส ในเดือนมกราคมปี 1918 กระตุ้นให้แพทย์ท้องถิ่นลอร์ลิ่ง มายเนอร์ (Loring Miner) ส่งคำเตือนไปยังวารสารวิชาการด้านการบริการสาธารณสุขของสหรัฐอเมริกา วันที่ 4 มีนาคม 1918 อัลเบิร์ต กิตเชล (Albert Gitchell) หน่วยปรุงอาหาร จากแฮสเค็ลล์เคาท์ตี ถูกรายงานว่าป่วยที่ฟอร์ทไรลีย์ ซึ่งในเวลานั้น อยู่ระหว่างการฝึกของทหารอเมริกันในช่วงสงครามโลกครั้งที่หนึ่ง ทำให้เขาเป็นเหยื่อรายแรกที่มีการบันทึกไว้ของไข้หวัดใหญ่[39][40][41] ในวันเดียวกันนั้น ทหาร 522 นายในค่ายถูกรายงานว่าป่วย[42]เมื่อวันที่ 11 มีนาคม 1918 ไวรัสได้มาถึงควีนส์ นครนิวยอร์ก[37] ความล้มเหลวในการใช้มาตรการป้องกันในเดือนมีนาคม/เมษายนถูกวิพากษ์วิจารณ์อย่างหนักในภายหลัง[4]

ในเดือนสิงหาคมปี 1918 สายพันธุ์ที่ดุร้ายยิ่งปรากฏขึ้นพร้อมกันในแบร็สต์ ประเทศฝรั่งเศส ในฟรีทาวน์ เซียร์ราลีโอน และในสหรัฐอเมริกา ในเดือนกันยายนที่ อู่ต่อเรือบอสตันและค่ายดีเวนส์ (Camp Devens) (ต่อมาเปลี่ยนชื่อเป็นฟอร์ตดีเวนส์ (Fort Devens)) ประมาณ 30 ไมล์ทางตะวันตกของบอสตัน ในไม่ช้า หน่วยทหารอื่นๆก็เริ่มเจ็บป่วยเช่นเดียวกับกองทหารที่ถูกส่งไปยังยุโรป[43]

อัตราการตาย

ทั่วโลก

มีผู้ติดเชื้อไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนประมาณ 500 ล้านคนทั่วโลก หรือประมาณหนึ่งในสามของประชากรโลก[1] ในการประเมินจำนวนผู้เสียชีวิตมีความแตกต่างกันเป็นอย่างมาก ไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนได้รับการพิจารณาว่าเป็นหนึ่งในโรคระบาดร้ายแรงที่มีผู้เสียชีวิตมากสุดในประวัติศาสตร์[46][47]

การประมาณการในปี 1991 ระบุว่าไวรัสฆ่าคนไประหว่าง 25 และ 39 ล้านคน[3] การประมาณการปี 2005 ระบุจำนวนผู้เสียชีวิตที่ 50 ล้านคน (ประมาณน้อยกว่า 3% ของประชากรโลก) และอาจสูงถึง 100 ล้านคน (มากกว่า 5%)[48][5] อย่างไรก็ตาม มีการประเมินใหม่ในปี 2018 คาดว่าจะมีผู้เสียชีวิตจำนวนประมาณ 17 ล้านคน[49] แม้ว่าจะมีการโต้แย้งกันก็ตาม[50] ในเวลานั้นมีประชากรโลกประมาณ 1.8 ถึง 1.9 พันล้านคน[51] ประมาณการเหล่านี้ มีความสอดคล้องกันคืออยู่ระหว่าง 1 และ 6 เปอร์เซ็นต์ของจำนวนประชากร

ไข้หวัดใหญ่สายพันธุ์นี้คร่าชีวิตผู้คนใน 24 สัปดาห์ได้มากกว่า HIV/AIDS ในระยะเวลา 24 ปี[6] อย่างไรก็ตาม อัตราการตายต่อจำนวนประชากรยังน้อยกว่ากาฬมรณะซึ่งระบาดเป็นเวลาหลายร้อยปี[52]

รูปแบบของการเสียชีวิต

การตายระลอกสอง

การระบาดทั่วระลอกที่สองในปี 1918 นั้นร้ายแรงและมีผู้เสียชีวิตมากยิ่งกว่าครั้งแรก การระบาดรอบแรกนั้นคล้ายกับโรคไข้หวัดใหญ่ทั่วไป ผู้ที่มีความเสี่ยงมากที่สุดคือผู้ป่วยและผู้สูงอายุ ขณะที่ผู้ที่ยังเด็ก ผู้มีสุขภาพแข็งแรงหายป่วยได้ง่าย เดือนสิงหาคม เมื่อการระบาดระลอกที่สองเริ่มขึ้นในฝรั่งเศส เซียร์ราลีโอน และสหรัฐอเมริกา[53] ไวรัสได้กลายพันธุ์ในสายพันธุ์ที่อันตรายกว่าเดิมมาก ตุลาคม 1918 เป็นเดือนที่มีอัตราการตายสูงที่สุดของการระบาด[54]

ความรุนแรงที่เพิ่มขึ้นนี้มีสาเหตุมาจากสถานการณ์ของสงครามโลกครั้งที่หนึ่ง[55] ในการดำรงชีวิตของพลเรือน การคัดเลือกโดยธรรมชาติสนับสนุนไวรัสสายพันธุ์อ่อน ผู้ที่ป่วยหนักพักรักษาตัวอยู่บ้าน ไวรัสสายพันธุ์อ่อนก็ดำรงวงจรชีวิต และแพร่กระจายสายพันธุ์อ่อนต่อไป ในสนามเพลาะ การคัดเลือกโดยธรรมชาติกลับตรงกันข้าน ทหารที่มีไวรัสสายพันธุ์อ่อนอยู่ในที่ที่พวกเขาอยู่ ในขณะที่ผู้ป่วยหนักถูกส่งตัวโดยรถไฟที่มีคนหนาแน่นไปโรงพยาบาลสนามที่มีผู้คนหนาแน่น และกระจายเชื้อไวรัสร้ายแรงออกไป การระบาดระลอกสองเริ่มขึ้น และไข้หวัดใหญ่แพร่กระจายไปทั่วโลกอย่างรวดเร็วอีกครั้ง ดังนั้น ผลที่สุดก็คือ ในช่วงการระบาดทั่ว เจ้าหน้าที่สาธารณสุขให้ความสนใจเมื่อไวรัสมาถึงสถานที่ที่มีการเปลี่ยนแปลงขนาดใหญ่ทางสังคม (มองหาไวรัสสายพันธุ์ร้ายแรง)[56]

ความจริงที่ว่าคนส่วนใหญ่ที่หายจากการติดเชื้อจากการระบาดรอบแรกได้มีภูมิคุ้มกัน แสดงให้เห็นว่ามันจะต้องเป็นไข้หวัดสายพันธุ์เดียวกัน ตัวอย่างที่เห็นได้ชัดคือในโคเปนเฮเกนซึ่งมีอัตราการตายรวมกันเพียง 0.29% (0.02% ในรอบแรกและ 0.27% ในรอบที่สอง) เพราะได้รับเชื้อจากการระบาดรอบแรกที่อันตรายน้อยกว่า[57] สำหรับอัตราการตายของประชากรในการระบาดรอบที่สองที่มากกว่านั้น เกิดจากกลุ่มเสี่ยง เช่น ทหารในสนามเพลาะ[58]

ระลอกที่สามปี 1919 และระลอกที่สี่ปี 1920

ในเดือนมกราคม 1919 ไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปนระลอกที่สามได้ระบาดที่ออสเตรเลีย จากนั้นก็แพร่กระจายอย่างรวดเร็วผ่านไปยังยุโรปและสหรัฐอเมริกาจนถึงเดือนมิถุนายนปี 1919[59][60][61] ประเทศส่วนใหญ่ที่ได้รับผลกระทบได้แก่ สเปน, เซอร์เบีย, เม็กซิโก และบริเตนใหญ่ ส่งผลให้มีผู้เสียชีวิตหลายแสนคน[62] แม้การระบาดระลอกสามจะรุนแรงน้อยกว่าระลอกที่สอง แต่ก็ยังมีผู้เสียชีวิตมากกว่าระลอกแรก

ในฤดูใบไม้ผลิปี 1920 มีการระบาดเล็กๆเกิดขึ้นเป็นระลอกที่สี่[63] ในพื้นที่โดดเดี่ยวประกอบด้วย มหานครนิวยอร์ก [64] สหราชอาณาจักร, ออสเตรีย, สแกนดิเนเวีย และบางเกาะในหมู่เกาะอเมริกาใต้[65] มีอัตราการตายต่ำมาก

ชุมชนที่ถูกทำลาย

พื้นที่ที่ได้รับผลกระทบเพียงเล็กน้อย

แอสไพรินเป็นพิษ

ในปี 2009 ในบทความที่ตีพิมพ์ใน Clinical Infectious Diseases (วารสารโรคติดเชื้อทางคลินิก) คาเรน สตาร์โค (Karen Starko) เสนอว่าแอสไพรินเป็นพิษมีส่วนสำคัญต่อการเสียชีวิต บนพื้นฐานจากรายงานการชันสูตรพลิกศพผู้ที่เสียชีวิตจากไข้หวัดใหญ่ในช่วงเวลา "death spike" ครั้งใหญ่ในเดือนตุลาคม 1918 ซึ่งเกิดขึ้นไม่นานหลังจากแพทย์ทหารของกองทัพสหรัฐและ Journal of the American Medical Association แนะนำให้ใช้ยาแอสไพรินปริมาณมากขนาด 8 ถึง 31 กรัมต่อวันเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของการรักษา ยาปริมาณนี้ทำให้ผู้ป่วย 33% เกิดอาหารหายใจเร็วกว่าปกติ และผู้ป่วย 3% เกิดอาการปอดบวมน้ำ[66]

สตาร์โกยังตั้งข้อสังเกตว่าการเสียชีวิตจำนวนมากในช่วงแรกแสดงให้เห็นว่าปอดมีน้ำหรือมีน้ำเลือดซึมซ่าน ในขณะที่ผู้เสียชีวิตในช่วงปลายแสดงอาการปอดอักเสบจากแบคทีเรีย เธอกล่าวว่าเหตุการณ์แอสไพรินเป็นพิษเป็นเพราะ "พายุมหาประลัย" ของเหตุการณ์สิทธิบัตรยาแอสไพรินของไบเออร์หมดอายุ หลายบริษัทรีบวิ่งเข้าไปทำกำไรและเพิ่มอุปทาน ซึ่งเกิดขึ้นใกล้เคียงกับเหตุการณ์ไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน และอาการของแอสไพรินเป็นพิษยังไม่เป็นที่รู้จักในเวลานั้น[66]

สมมติฐานอัตราการตายทั่วโลกที่สูงนั้นเกิดจากแอสไพรินเป็นพิษนี้ถูกตั้งคำถามในจดหมายถึงวารสารที่ตีพิมพ์ในเดือนเมษายน 2010 โดย แอนดรูว์ นอยเมอร์ (Andrew Noymer) และ เดซี่ แคาร์รออน (Daisy Carreon) จากมหาวิทยาลัยแคลิฟอร์เนีย เออร์ไวน์ และ นีล จอห์นสัน (Niall Johnson) คณะกรรมาธิการความปลอดภัยและคุณภาพการดูแลสุขภาพออสเตรเลีย พวกเขาตั้งคำถามถึงทฤษฎีการใช้ประโยชน์ได้กว้างขวางของแอสไพริน เนื่องจากอัตราการตายสูงในประเทศต่างๆ เช่น อินเดีย ที่มีแอสไพรินน้อยหรือไม่มีการเข้าถึงเลย เมื่อเทียบกับอัตราการตายในบางสถานที่ที่แอสไพรินมีมากมาย[67]

พวกเขาสรุปว่า "การตั้งสมมติฐานเกี่ยวกับซาลิไซลิก (แอสไพริน) เป็นพิษ เป็นเรื่องยากที่จะสนับสนุนซึ่งคำอธิบายปฐมภูมิสำหรับความรุนแรงที่ผิดปกติของการระบาดทั่วของไข้หวัดใหญ่ในปี 1918–1919"[67] สตาร์โกตอบโต้โดยกล่าวว่ามีหลักฐานโดยเรื่องเล่าของการใช้แอสไพรินในประเทศอินเดีย และเป็นที่ถกเถียงกันอยู่ว่า ถ้าการใช้แอสไพรินเกินกำหนดไม่ได้มีส่วนทำให้อัตราการตายในอินเดียสูง แต่มันคงเป็นปัจจัยที่ทำให้เกิดอัตราการตายที่สูง ในพื้นที่ที่ปัจจัยรุนแรงอื่นๆที่มีอยู่ในอินเดียมีบทบาทน้อย[68]

จุดสิ้นสุดของการระบาด

หลังจากการระบาดรุนแรงรอบที่สองในช่วงปลายปี 1918 ผู้ป่วยรายใหม่ลดลงอย่างฉับพลัน แทบจะไม่ผู้ป่วยเลยหลังจากผ่านจุดระบาดสูงสุดในคลื่นลูกที่สอง[6] ตัวอย่างเช่นในฟิลาเดลเฟีย มีผู้เสียชีวิต 4,597 รายเมื่อสิ้นสุดสัปดาห์ในวันที่ 16 ตุลาคม แต่เมื่อวันที่ 11 พฤศจิกายนไข้หวัดใหญ่กลับหายตัวไปจากเมืองอย่างไร้ร่องรอย คำอธิบายหนึ่งสำหรับการลดลงอย่างรวดเร็วของโรคนี้คือ แพทย์มีประสิทธิภาพมากขึ้นในการป้องกันและรักษาโรคปอดบวมที่พัฒนาขึ้นหลังจากผู้ป่วยติดเชื้อไวรัส อย่างไรก็ตาม จอห์น แบร์รี่ (John Barry) ระบุไว้ในหนังสือ The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague In History ของเขาว่า นักวิจัยไม่พบหลักฐานที่สนับสนุนคำอธิบายนี้[69] ยังมีบางกรณีที่ผู้ป่วยถึงแก่ชีวิตในมีนาคม 1919 ผู้เล่นคนหนึ่งในการแข่งขันรอบรองชนะเลิศถ้วยสแตนลีย์ 1919 ได้เสียชีวิตจากไข้หวัดใหญ่สเปน

อีกทฤษฎีหนึ่งกล่าวว่าเชื้อ 1918 ไวรัส ได้กลายพันธุ์อย่างรวดเร็วจนกลายเป็นสายพันธุ์ที่มีความร้ายแรงน้อยลง นี่เป็นเหตุการณ์ที่เกิดขึ้นทั่วไปกับไวรัสไข้หวัดใหญ่กล่าวคือ มีแนวโน้มว่าไวรัสก่อโรคจะมีความร้ายแรงน้อยลงตามกาลเวลา เนื่องจากโฮสต์ของสายพันธุ์ที่อันตรายกว่ามีแนวโน้มที่จะตายจากไปจนหมด[69]

ผลกระทบระยะยาว

จากการศึกษาปี 2006 ใน Journal of Political Economy (วารสารเศรษฐศาสตร์การเมือง) พบว่า "เด็กในครรภ์ระหว่างการระบาดทั่วจะมีความสำเร็จทางการศึกษาลดลง, อัตราความพิการทางร่างกายเพิ่มขึ้น, รายได้ลดลง, สถานะทางเศรษฐกิจและสังคมที่ตกต่ำ, และได้รับเงินโอนสูงขึ้นเมื่อเทียบกับรุ่นอื่น"[70] จากการศึกษาปี 2018 พบว่าการระบาดใหญ่ลดความสำเร็จทางการศึกษาในประชากร[71]

ไข้หวัดใหญ่มีความเชื่อมโยงกับการระบาดของสมองอักเสบแบบไม่เคลื่อนไหวในคริสต์ทศวรรษที่ 1920[7]

อ้างอิง

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Taubenberger & Morens 2006.

- ↑ Institut Pasteur. La Grippe Espagnole de 1918 (Powerpoint presentation in French).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Patterson & Pyle 1991.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Billings 1997.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Johnson & Mueller 2002.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Barry 2004.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Vilensky, Foley & Gilman 2007.

- ↑ Porras-Gallo & Davis 2014.

- ↑ Galvin 2007.

- ↑ "Spanish flu facts". Channel 4 News. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 27 January 2010.

- ↑ Anderson, Susan (29 August 2006). "Analysis of Spanish flu cases in 1918–1920 suggests transfusions might help in bird flu pandemic". American College of Physicians. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 November 2011. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ Barry 2004, p. 171.

- ↑ Harvey, Josephine (18 March 2020). "Yes, Viruses Used To Be Named After Places. Here's Why They Aren't Anymore". สืบค้นเมื่อ 8 April 2020.

{{cite news}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ "WHO issues best practices for naming new human infectious diseases". World Health Organization. 8 May 2015. สืบค้นเมื่อ 8 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (ลิงก์) - ↑ "Pandemic influenza: an evolving challenge". World Health Organization. 22 May 2018. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 March 2020.

- ↑ "Influenza pandemic of 1918–19". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 4 March 2020. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 March 2020.

- ↑ Chodosh, Sara (18 March 2020). "What the 1918 flu pandemic can teach us about COVID-19, in four charts". PopSci. สืบค้นเมื่อ 20 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ "EU Research Profile on Dr. John Oxford". คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 May 2009. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 May 2009.

- ↑ Connor, Steve (8 January 2000). "Flu epidemic traced to Great War transit camp". The Guardian. UK. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 May 2009. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 May 2009.

- ↑ Oxford JS, Lambkin R, Sefton A, Daniels R, Elliot A, Brown R, Gill D (January 2005). "A hypothesis: The conjunction of soldiers, gas, pigs, ducks, geese, and horses in northern France during the Great War provided the conditions for the emergence of the "Spanish" influenza pandemic of 1918–1919" (PDF). Vaccine. 23 (7): 940–945. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.035. PMID 15603896. เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 March 2020.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Shanks GD (January 2016). "No evidence of 1918 influenza pandemic origin in Chinese laborers/soldiers in France". Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 79 (1): 46–48. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2015.08.009. PMID 26542935.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Michael Worobey, Jim Cox, Douglas Gill, The origins of the great pandemic, Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, Volume 2019, Issue 1, 2019, Pages 18–25

- ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อ:2 - ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Langford, Christopher (2005). "Did the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic Originate in China?". Population and Development Review. Vol. 31, No. 3 (Sep., 2005) (3): 473–505. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00080.x. JSTOR 3401475.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ↑ Cheng, K.F. "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Volume 11, Issue 4, July 2007: 360–364. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 5 December 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 5 March 2020.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ↑ 26.0 26.1 Cheng, K.F. "What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic?". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. Volume 11, Issue 4, July 2007: 360–364. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 5 December 2019. สืบค้นเมื่อ 5 March 2020.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ↑ Klein, Christopher. "China Epicenter of 1918 Flu Pandemic, Historian Says". เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 5 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 5 March 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal ต้องการ|journal=(help) - ↑ Vergano, Dan. "1918 Flu Pandemic That Killed 50 Million Originated in China, Historians Say". National Geographic. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 3 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 5 March 2020.

- ↑ Saunders-Hastings, Patrick R.; Krewski, Daniel (6 December 2016). "Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission". Pathogens. 5 (4): 66. doi:10.3390/pathogens5040066. ISSN 2076-0817. PMC 5198166. PMID 27929449.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Hannoun, Claude (1993). "La Grippe". Documents de la Conférence de l'Institut Pasteur. La Grippe Espagnole de 1918. Ed Techniques Encyclopédie Médico-Chirurgicale (EMC), Maladies infectieuses. Vol. 8-069-A-10.

- ↑ Humphries 2014.

- ↑ Vergano, Dan (24 January 2014). "1918 Flu Pandemic That Killed 50 Million Originated in China, Historians Say". National Geographic. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 26 January 2014. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Price-Smith 2008.

- ↑ Sherman, Irwin W. (2007). Twelve diseases that changed our world. Washington, DC: ASM Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-55581-466-3.

{{cite book}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ Qureshi 2016, p. 42.

- ↑ Ewald 1994.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Spanish flu strikes during World War I". 14 January 2010. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Illing, Sean (20 March 2020). "The most important lesson of the 1918 influenza pandemic: Tell the damn truth". Vox (ภาษาอังกฤษ). เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 25 March 2020.

John M. Barry : The government lied. They lied about everything. We were at war and they lied because they didn’t want to upend the war effort. You had public health leaders telling people this was just the ordinary flu by another name. They simply didn’t tell the people the truth about what was happening.

- ↑ Barry JM (January 2004). "The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications". Journal of Translational Medicine. 2 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-2-3. PMC 340389. PMID 14733617.

- ↑ Bynum, Bill (14 March 2009). "Stories of an influenza pandemic" (PDF). The Lancet. 373 (9667): 885–886. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60530-4. เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 7 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 March 2018.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ Rego Barry, Rebecca (13 November 2018). "Exhuming the Flu". Distillations. Science History Institute. 4 (3): 40–43. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 6 February 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 February 2020.

- ↑ "1918 Flu (Spanish flu epidemic)". Avian Bird Flu. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Byerly CR (April 2010). "The U.S. military and the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919". Public Health Rep. 125 Suppl 3: 82–91. PMC 2862337. PMID 20568570.

- ↑ Taubenberger & Morens 2006, pp. 15–22.

- ↑ CDC 2009.

- ↑ "Ten things you need to know about pandemic influenza (update of 14 October 2005)" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record (Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire). 80 (49–50): 428–431. 9 December 2005. PMID 16372665.

- ↑ Jilani, TN; Jamil, RT; Siddiqui, AH (14 December 2019). "H1N1 Influenza (Swine Flu)". NCBI. PMID 30020613. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 March 2020.

- ↑ Knobler 2005.

- ↑ P. Spreeuwenberg; และคณะ (1 December 2018). "Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". American Journal of Epidemiology. 187 (12): 2561–2567. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy191. PMID 30202996.

- ↑ Chandra, Siddharth; Christensen, Julia (2 March 2019). "Re: "reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic"". Am. J. Epid. 188 (7): 1404–1406. doi:10.1093/aje/kwz044. PMID 30824934. and response Spreeuwenberg, Peter; Kroneman, Madelon; Paget, John (2 March 2019). "The Authors Reply" (PDF). Am. J. Epid. 188 (7): 1405–1406. doi:10.1093/aje/kwz041. PMID 30824908. เก็บ (PDF)จากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 12 March 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 March 2020.

- ↑ "Historical Estimates of World Population". คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 9 July 2012. สืบค้นเมื่อ 29 March 2013.

- ↑ Robinson Meyer (29 April 2016). "Human extinction isn't that unlikely". The Atlantic. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 1 May 2016. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 February 2018.

- ↑ Pandemic Influenza (PDF). Science and Technology Committee (Report). Report of Session 2005–2006. Vol. 4th. Broers, Alec, Baron Broers (chairman). UK House of Lords. 16 December 2005. HL Paper 88. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 8 May 2009. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 May 2009.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: others (ลิงก์) - ↑ แม่แบบ:Cite media[ต้องการอ้างอิงเต็มรูปแบบ]

- ↑ Gladwell 1997, p. 55.

- ↑ Gladwell 1997, p. 63.

- ↑ Fogarty International Center. "Summer Flu Outbreak of 1918 May Have Provided Partial Protection Against Lethal Fall Pandemic". Fic.nih.gov. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 27 July 2011. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 May 2012.

- ↑ Gladwell 1997, p. 56.

- ↑ Why the Second Wave of the 1918 Spanish Flu Was So Deadly History.com - Retrieved 8 May 2020

- ↑ Radusin, Milorad (2012). "The Spanish Flu – Part II: the second and third wave". Vojnosanitetski pregled. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ "1918 Pandemic Influenza: Three Waves". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 May 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 April 2020.

- ↑ Najera, Rene F. (2 January 2019). "Influenza in 1919 and 100 Years Later". College of Physicians of Philadelphia. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ Erkoreka, Anton (30 November 2009). "Origins of the Spanish Influenza pandemic (1918–1920) and its relation to the First World War". Journal of Molecular and Genetic Medicine : An International Journal of Biomedical Research. National Institutes of Health. 3 (2): 190–94. doi:10.4172/1747-0862.1000033. PMC 2805838. PMID 20076789.

{{cite journal}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|name-list-format=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|name-list-style=) (help) - ↑ Yang W, Petkova E, Shaman J (March 2014). "The 1918 influenza pandemic in New York City: age-specific timing, mortality, and transmission dynamics". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. National Institutes of Health. 8 (2): 177–88. doi:10.1111/irv.12217. PMC 4082668. PMID 24299150.

- ↑ "How the 1918 flu pandemic rolled on for years: a snapshot from 1920". The Guardian. สืบค้นเมื่อ 30 April 2020.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Starko 2009.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Noymer, Carreon & Johnson 2010.

- ↑ Starko 2010.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Barry 2004b.

- ↑ Almond, Douglas (1 August 2006). "Is the 1918 Influenza Pandemic Over? Long‐Term Effects of In Utero Influenza Exposure in the Post‐1940 U.S. Population". Journal of Political Economy. 114 (4): 672–712. doi:10.1086/507154. ISSN 0022-3808.

- ↑ Beach, Brian; Ferrie, Joseph P.; Saavedra, Martin H. (2018). "Fetal shock or selection? The 1918 influenza pandemic and human capital development". nber.org. doi:10.3386/w24725. เก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 18 June 2018. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 June 2018.

แหล่งข้อมูลอื่น