ผู้ใช้:Zambo/รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งญี่ปุ่น

| Zambo/รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งญี่ปุ่น | |

|---|---|

| |

| ข้อมูลทั่วไป | |

| เว็บไซต์ | |

| [1] |

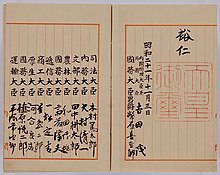

รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งญี่ปุ่น (ญี่ปุ่น: (ชินจิตะอิ) 日本国憲法, (คยูจิตะอิ)日本國憲法; โรมาจิ: Nihon-Koku Kenpō; ทับศัพท์: นิฮงโคะกุเค็นโป) เป็นกฎหมายสูงสุดและเป็นกฎหมายแม่บทแห่งกฎหมายทั้งปวงของประเทศญี่ปุ่น นับแต่เปลี่ยนแปลงประเทศเข้าสู่สมัยใหม่เป็นต้นมา ญี่ปุ่นประกาศใช้รัฐธรรมนูญมาแล้วสองฉบับ คือ ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2432 และฉบับ พ.ศ. 2489 อันเป็นฉบับปัจจุบันซึ่งกำหนดการปกครองของประเทศให้อยู่ภายในระบอบประชาธิปไตยแบบรัฐสภา มีพระจักรพรรดิทรงเป็นประมุขแห่งรัฐแต่ในทางพิธีการ มิใช่ประมุขแห่งรัฐอย่างเป็นทางการ นอกจากนี้ยังบัญญัติหลักการ "อำนาจอธิปไตยเป็นของปวงชน" (ประชาธิปไตย) เพื่อลบล้างทฤษฎีจากรัฐธรรมนูญฉบับก่อนที่ว่า "อำนาจอธิปไตยเป็นของพระจักรพรรดิ" (สมบูรณาญาสิทธิราชย์) นอกจากนี้ รัฐธรรมนูญฉบับปัจจุบันของญี่ปุ่นยังได้สมญานามว่า "รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งสันติ" (ญี่ปุ่น: 平和憲法; โรมาจิ: Heiwa-Kenpō; ทับศัพท์: เฮวะเค็นโป) เนื่องจากบทบัญญัติที่ว่าด้วยการสละสงคราม (มาตรา 9) อันโดดเด่นซึ่งร่างขึ้นโดยกองกำลังผสมระหว่างชาติฝ่ายสัมพันธมิตรที่เข้ายึดญี่ปุ่นภายหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 โดยวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อแทนที่ระบอบสมบูรณาญาสิทธิราชย์แบบแสนยนิยมด้วยระบอบประชาธิปไตยแบบเสรีนิยม

นับแต่มีการประกาศใช้มา ยังไม่มีการแก้ไขเพิ่มเติมรัฐธรรมนูญฉบับ พ.ศ. 2489 เลย

ประวัติ[แก้]

รัฐธรรมนูญเมจิ (พ.ศ. 2432)[แก้]

รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งจักรวรรดิญี่ปุ่น (ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2432) หรือที่รู้จักกันว่า "รัฐธรรมนูญเมจิ" หรือ "รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งจักรพรรดิ" เป็นรัฐธรรมนูญอย่างสมัยใหม่ฉบับแรกของญี่ปุ่น โดยเป็นส่วนหนึ่งในการคืนสู่ราชบัลลังก์ของจักรพรรดิเมจิ สาระสำคัญเป็นการกำหนดรูปแบบการปกครองประเทศเป็นระบอบราชาธิปไตยภายใต้รัฐธรรมนูญโดยมีรัฐธรรมนูญของปรัสเซียเป็นต้นแบบ ตามรัฐธรรมนูญนี้ พระจักรพรรดิทรงเป็นประมุขแห่งรัฐ มีพระราชอำนาจในทางบริหารและทางการเมืองโดยนิตินัย แต่ในทางพฤตินัยแล้วต้องทรงได้รับการสนับสนุนและกำกับดูแลจากคณะรัฐมนตรีซึ่งมีนายกรัฐมนตรีนายหนึ่งอันเลือกสรรโดยองคมนตรีสภา สำหรับนายกรัฐมนตรีและรัฐมนตรีคนอื่น ๆ นั้นไม่จำเป็นต้องเป็นสมาชิกสภานิติบัญญัติแห่งชาติผู้มาจากการเลือกตั้งแต่อย่างใด

รัฐธรรมนูญฉบับนี้สิ้นสุดลงเมื่อวันที่ 3 พฤษภาคม พ.ศ 2490 อันเป็นวันที่รัฐธรรมนูญฉบับใหม่มีผลใช้บังคับ

ปฏิญญาพอทสดัม[แก้]

ในวันที่ 26 กรกฎาคม พ.ศ. 2488 เซอร์วินสตัน เลโอนาร์ด สเปนเซอร์-เชอร์ชิล นายแฮร์รี เอส. ทรูแมน และพลเอกเจียงไคเช็ก ผู้บัญชาการกองผสมระหว่างชาติฝ่ายสัมพันธมิตร ได้ประกาศ "ปฏิญญาพอทสดัม" (อังกฤษ: Potsdam Declaration) อันเรียกร้องให้ญี่ปุ่นยอมจำนนโดยไร้เงื่อนไข ในปฏิญญาฯ ยังได้กำหนดเป้าหมายหลักให้ญี่ปุ่นปฏิบัติตามภายหลังยอมจำนนแล้ว ว่าให้รัฐบาลญี่ปุ่นทำลายสิ่งกีดขวางทั้งปวง และทะนุบำรุงแนวโน้มทางประชาธิปไตยให้แก่ประชาชนของตน นอกจากนี้ เสรีภาพในการพูด เสรีภาพในทางศาสนา และเสรีภาพทางความคิด กับทั้งสิทธิมนุษยชนขั้นพื้นฐานจะต้องได้รับการสถาปนาขึ้นอย่างแท้จริง ปฏิญญาฯ ยังปรากฏข้อความอีกว่า กองกำลังผสมของฝ่ายสัมพันธมิตรจะได้ถอนตัวออกจากญี่ปุ่นโดยไม่ชักช้า เมื่อบรรลุวัตถุประสงค์ดังกล่าว ตลอดทั้งญี่ปุ่นมีรัฐบาลที่รักสงบและรู้รับผิดชอบแล้ว

ฝ่ายสัมพันธมิตรว่า มิได้มีความประสงค์เพียงแต่จะลงทัณฑ์หรือแก้ไขความเลวร้ายของลัทธิแสนยนิยมเท่านั้น แต่จะได้

Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established" (Section 10). In addition, the document stated: "The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government" (Section 12). The Allies sought not merely punishment or reparations from a militaristic foe, but fundamental changes in the nature of its political system. In the words of political scientist Robert E. Ward: "The occupation was perhaps the single most exhaustively planned operation of massive and externally directed political change in world history."

กระบวนการร่างรัฐธรรมนูญ[แก้]

The wording of the Potsdam Declaration—"The Japanese Government shall remove all obstacles..."—and the initial postsurrender measures taken by Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), suggest that neither he nor his superiors in Washington intended to impose a new political system on Japan unilaterally. Instead, they wished to encourage Japan's new leaders to initiate democratic reforms on their own. But by early 1946, MacArthur's staff and Japanese officials were at odds over the most fundamental issue, the writing of a new constitution. Emperor Showa, Prime Minister Shidehara Kijuro and most of the cabinet members were extremely reluctant to take the drastic step of replacing the 1889 Meiji Constitution with a more liberal document[1]. In late 1945, Shidehara appointed Joji Matsumoto, state minister without portfolio, head of a blue-ribbon committee of constitutional scholars to suggest revisions. The Matsumoto Commission's recommendations, made public in February 1946, were quite conservative (described by one Japanese scholar in the late 1980s as "no more than a touching-up of the Meiji Constitution"). MacArthur rejected them outright and ordered his staff to draft a completely new document.

Much of it was drafted by two senior army officers with law degrees: Milo Rowell and Courtney Whitney. The articles about equality between men and women are reported to be written by Beate Sirota. Although the document's authors were non-Japanese, they took into account the Meiji Constitution, the demands of Japanese lawyers, and the opinions of pacifist political leaders such as Shidehara and Yoshida Shigeru. The draft was presented to surprised Japanese officials on 13 February, 1946. On 6 March, 1946, the government publicly disclosed an outline of the pending constitution. On 10 April elections were held to the House of Representatives of the Ninetieth Imperial Diet, which would consider the proposed constitution. The election law having been changed, this was the first general election in Japan in which women were permitted to vote.

The MacArthur draft, which proposed a unicameral legislature, was changed at the insistence of the Japanese to allow a bicameral legislature, both houses being elected. In most other important respects, however, the ideas embodied in the 13 February document were adopted by the government in its own draft proposal of 6 March. These included the constitution's most distinctive features: the symbolic role of the Emperor, the prominence of guarantees of civil and human rights, and the renunciation of war.

การมีมติเห็นชอบ[แก้]

It was decided that in adopting the new document the Meiji Constitution would not be violated, but rather legal continuity would be maintained. Thus the 1946 constitution was adopted as an amendment to the Meiji Constitution in accordance with the provisions of Article 73 of that document. Under Article 73 the new constitution was formally submitted to the Imperial Diet by the Emperor, through an imperial rescript issued on 20 June. The draft constitution was submitted and deliberated upon as the Bill for Revision of the Imperial Constitution. The old constitution required that the bill receive the support of a two-thirds majority in both houses of the Diet in order to become law. After both chambers had made some amendments the House of Peers approved the document on 6 October; it was adopted in the same form by the House of Representatives the following day, with only five members voting against, and finally became law when it received the Emperor's assent on 3 November. Under its own terms the constitution came into effect six months later on 3 May, 1947.

การเสนอแก้ไขรัฐธรรมนูญในชั้นปัจจุบัน[แก้]

The new constitution would not have been written the way it was had MacArthur and his staff allowed Japanese politicians and constitutional experts to resolve the issue as they wished. The document's foreign origins have, understandably, been a focus of controversy since Japan recovered its sovereignty in 1952. Yet in late 1945 and 1946, there was much public discussion on constitutional reform, and the MacArthur draft was apparently greatly influenced by the ideas of certain Japanese liberals. The MacArthur draft did not attempt to impose a United States-style presidential or federal system. Instead, the proposed constitution conformed to the British model of parliamentary government, which was seen by the liberals as the most viable alternative to the European absolutism of the Meiji Constitution.

After 1952 conservatives and nationalists attempted to revise the constitution to make it more "Japanese", but these attempts were frustrated for a number of reasons. One was the extreme difficulty of amending it. Amendments require approval by two-thirds of the members of both houses of the National Diet before they can be presented to the people in a referendum (Article 96). Also, opposition parties, occupying more than one-third of the Diet seats, were firm supporters of the constitutional status quo. Even for members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the constitution was advantageous. They had been able to fashion a policy-making process congenial to their interests within its framework. Yasuhiro Nakasone, a strong advocate of constitutional revision during much of his political career, for example, downplayed the issue while serving as prime minister between 1982 and 1987.

บทบัญญัติหลัก[แก้]

โครงสร้าง[แก้]

รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งญี่ปุ่นฉบับปัจจุบัน (ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2489) มีความยาวห้าพันคำญี่ปุ่น ประกอบด้วยอารัมภบทและมาตรากฎหมายจำนวนหนึ่งร้อยสามมาตรา โดยจัดแบ่งเป็นสิบเอ็ดหมวด ดังนี้

- หมวด 1 : พระจักรพรรดิ(มาตรา 1-8)

- หมวด 2 : การสละสงคราม (มาตรา 9)

- หมวด 3 : สิทธิและหน้าที่ของประชาชน (มาตรา 10-40)

- หมวด 4 : สภานิติบัญญัติแห่งชาติ (มาตรา 41-64)

- หมวด 5 : คณะรัฐมนตรี (มาตรา 65-75)

- หมวด 6 : ตุลาการ (มาตรา 76-82)

- หมวด 7 : การเงิน (มาตรา 83-91)

- หมวด 8 : การปกครองส่วนท้องถิ่น (มาตรา 92-95)

- หมวด 9 : การแก้ไขเพิ่มเติมรัฐธรรมนูญ (มาตรา 96)

- หมวด 10 : กฎหมายสูงสุด (มาตรา 97-99)

- หมวด 11 : บทเบ็ดเตล็ด (มาตรา 100-103)

หลักการพื้นฐาน[แก้]

รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งญี่ปุ่นได้ประกาศเป็นมั่นเหมาะไว้ในอารัมภบทซึ่งหลักการ "อำนาจอธิปไตยเป็นของปวงชน" (ประชาธิปไตย) โดยอารัมภบทนี้ผู้ร่างได้เขียนเป็นประกาศในนามของปวงชนชาวญี่ปุ่น ใจความตอนหนึ่งว่า

...เราประกาศว่าอธิปไตยเป็นของปวงชน และสถาปนารัฐธรรมนูญนี้ขึ้นไว้โดยมั่นคง รัฐบาลนั้นเป็นความไว้วางใจอย่างแท้จริงของประชาชน หน้าที่ของรัฐบาลจึงมาจากการมอบหมายของประชาชน อำนาจของรัฐบาลนั้นเล่าก็ต้องกระทำเสมอเป็นผู้แทนปวงชน และที่สุดประโยชน์ทั้งปวงก็จะตกอยู่แก่ประชนชน นี้เป็นหลักการสากลของมนุษยชาติอันก่อให้เกิดเป็นรัฐธรรมนูญนี้...

ความมุ่งประสงค์ประการหนึ่งแห่งอารัมภบทที่เขียนขึ้นในภาษาเช่นนี้ก็เพื่อลบล้างทฤษฎีของรัฐธรรมนูญฉบับก่อน (ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2432) ที่ว่า "อำนาจอธิปไตยเป็นของพระจักรพรรดิ" (สมบูรณาญาสิทธิราชย์) โดยฉบับปัจจุบันบัญญัติว่าพระจักรพรรดิทรงเป็นเพียงสัญลักษณ์แห่งรัฐและความสามัคคีของชนในรัฐ โดยตำแหน่งพระจักรพรรดินั้น "ประชาชนผู้เป็นเจ้าของอำนาจอธิปไตย" เป็นผู้ถวายให้ แสดงให้เห็นว่ารัฐธรรมนูญฉบับนี้ยืนยันหลักการพื้นฐานของสิทธิมนุษยชนตามลัทธิเสรีนิยม นอกจากนี้ มาตรา 97 ยังบัญญัติอีกว่า

มาตรา 97 สิทธิมนุษยชนขั้นพื้นฐานที่รัฐธรรมนูญนี้รับรองไว้ให้แก่ชนชาวญี่ปุ่นล้วนเป็นผลิตผลแห่งการดิ้นรนจะเป็นอิสระของมนุษยชาติที่นับเนื่องมานมนาน มนุษย์เราได้ฟันฝ่าบททดสอบนานัปการอันเรียกร้องหาความอดทน เพื่อสร้างความเชื่อมั่นให้แก่ชนรุ่นเราและชาวรุ่นหน้า สิทธิเหล่านั้นจึงต้องได้รับการยึดถือชั่วกัปชั่วกัลป์ โดยผู้ใดจะละเมิดมิได้

องค์กรของรัฐบาล[แก้]

รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งญี่ปุ่น (ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2489) ได้สถาปนาการปกครองระบอบประชาธิปไตยแบบรัฐสภา มีพระจักรพรรดิทรงเป็นประมุขแห่งรัฐแต่ทางพิธีการ โดยไม่ทรงมีพระราชอำนาจสำรองคือพระราชอำนาจที่ตกค้างมาจากระบอบเก่าเลย ต่างกับประเทศอื่น ๆ ที่ใช้ระบอบการปกครองเดียวกัน เช่น ไทย

อำนาจนิติบัญญัตินั้นบริหารโดย สภานิติบัญญัติแห่งชาติ หรือที่เรียกว่า "ไดเอต" (อังกฤษ: Diet) อันประกอบด้วยสภาสองสภา คือ สภาผู้แทนราษฎร (สภาล่าง) และมนตรีสภา (สภาสูง) ทั้งนี้ โดยที่แต่ก่อนมนตรีสภาประกอบด้วยสมาชิกที่เป็นขุนนางและราชวงศ์ รัฐธรรมนูญฉบับนี้จึงบัญญัติว่าสมาชิกของสภาทั้งสองต้องเป็นผู้ที่ได้รับการเลือกตั้งจากประชาชนโดยตรง

อำนาจบริหารนั้นบริหารโดย คณะรัฐมนตรี ซึ่งบัญญัติให้ต้องปฏิบัติหน้าที่ด้วยความรับผิดชอบต่อสภานิติบัญญัติแห่งชาติ มีนายกรัฐมนตรีนายหนึ่งซึ่งพระจักรพรรดิทรงแต่งตั้งตามคำกราบบังคมทูลของประธานสภานิติบัญญัติแห่งชาติเป็นหัวหน้ารัฐบาล

ส่วนอำนาจตุลาการนั้นบริหารโดยศาลทั้งปวงในพระนามาภิไธยพระจักรพรรดิ มี ศาลสูงสุด เป็นประมุข โดยประธานศาลสูงสุดนั้นพระจักรพรรดิทรงแต่งตั้งตามคำกราบบังคมทูลของนายกรัฐมนตรี ส่วนตุลาการคนอื่น ๆ คณะรัฐมนตรีเป็นผู้แต่งตั้ง และเมื่อครบกำหนด ๆ หนึ่ง การแต่งตั้งนี้จะต้องได้รับการพิจารณาทบทวนโดยประชาชนทั่วประเทศ หากประชาชนมีมติไม่เห็นชอบด้วย ตุลาการผู้นั้นก็จะพ้นจากตำแหน่งทันที

สิทธิและหน้าที่ของบุคคล[แก้]

แนวคิดเรื่องสิทธิและหน้าที่ของปวงชนชาวญี่ปุ่นตามระบอบประชาธิปไตยปรากฏเด่นชัดอย่างยิ่งในช่วงหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 ซึ่งโดยรวมจากมาตราในรัฐธรรมนูญฉบับปัจจุบัน (ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2489) ทั้งหมดหนึ่งร้อยสามมาตราแล้ว ที่เกี่ยวกับสิทธิและหน้าที่ของบุคคลมีด้วยกันสามสิบเอ็ดมาตรา กระนั้น รัฐธรรมนูญฉบับก่อนหน้านี้ (ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2432) หรือที่เรียกกันว่า "รัฐธรรมนูญเมจิ" ก็มีบทบัญญัติในลักษณะเดียวกัน แต่มิได้กว้างขวางเท่า เช่น บัญญัติว่าสิทธิและเสรีภาพในการเชื่อการนับถือนั้นได้รับการรับรองตราบเท่าที่ไม่ขัดกับหน้าที่ของพสกนิกร ซึ่งขณะนั้นชาวญี่ปุ่นมีหน้าที่ต้องเคารพนับถือเทวสภาพของพระจักรพรรดิ และผู้นับถือศาสนาคริสต์ซึ่งปฏิเสธที่จะเคารพนับถือดังกล่าวก็ถูกกล่าวหาว่ากระทำความผิดต่อองค์พระมหากษัตริย์

- เสรีภาพ : รัฐธรรมนูญฉบับปัจจุบันรับรองว่า "ความเป็นมนุษย์ของประชาชนทั้งปวงย่อมได้รับการเคารพ ในการนิติบัญญัติและการบริหารกิจการอื่น ๆ ของรัฐ ให้คำนึงถึงสิทธิที่จะดำรงอยู่ เสรีภาพ และการเข้าถึงความผาสุกของประชาชนเป็นที่ตั้ง ตราบเท่าที่สิ่งเหล่านี้ไม่กระทบกระเทือนสวัสดิภาพประชาชน" (มาตรา 13)

- ความเสมอภาค : รัฐธรรมนูญฉบับปัจจุบันรับรองความเสมอภาคของบุคคลทุกคนในทางกฎหมาย มีการบัญญัติว่า "บุคคลทุกคนมีความเสมอภาคกันตามกฎหมาย การเลือกปฏิบัติทางการเมือง เศรษฐกิจ หรือสังคมเพราะเหตุทางเชื้อชาติ ลัทธิความเชื่อ เพศ สถานภาพทางสังคม หรือเหล่ากำเนิด จะกระทำมิได้" (มาตรา 14 วรรค 1)

- การปฏิเสธชนชั้นขุนนาง : มาตรา 14 วรรค 2 แห่งรัฐธรรมนูญนี้บัญญัติว่า "ไม่มีชนชั้นขุนนางและฐานันดรศักดิ์" นอกจากนี้ในวรรคถัดมายังว่า "การได้รับรางวัลเกียรติยศ ราชอิสริยาภรณ์ หรือยศถาบรรดาศักดิ์ใด ๆ ย่อมไม่ส่งผลให้บุคคลมีเอกสิทธิ์ กับทั้งให้สิ้นสุดลงเมื่อผู้ครอบครองสิ่งดังกล่าวอยู่ในวันที่รัฐธรรมนูญนี้มีผลใช้บังคับหรือผู้ที่จะได้รับในภายภาคหน้าถึงแก่ความตายแล้ว"

- การเลือกตั้งตามระบอบประชาธิปไคย : มาตรา 15 วรรค 1 ว่า "สิทธิในการเลือกตั้งและถอดถอนเจ้าหน้าที่ของรัฐเป็นสิทธิของประชาชนอันไม่อาจถ่ายโอนให้แก่กันได้" นอกจากนี้ยังมีการรับรองสิทธิของผู้บรรลุนิติภาวะ (ยี่สิบปีบริบูรณ์เป็นต้นไป) ในการเลือกตั้ง และรับรองการลงคะแนนเลือกตั้งลับด้วย

- การป้องกันการเอาคนลงเป็นทาส : ได้รับการรับรองไว้ในมาตรา 18 และการให้จำยอมรับภาระเป็นสิ่งต้องห้ามเว้นแต่ในการลงโทษทางอาญา

- การเป็นกลางทางศาสนา : ไม่ได้มีบัญญัติไว้อย่างชัดเจนเกี่ยวกับสถาบันทางศาสนา แต่ในมาตรา 20 วรรค 3 ว่า "รัฐและองค์กรของรัฐจะจัดการศึกษาทางศาสนาและจะประกอบพิธีกรรมอื่นใดทางศาสนามิได้"

- เสรีภาพในการชุมนุม ในการพูด ในการรวมกันเป็นสมาคม และในความลับแห่งการติดต่อสื่อสารกัน : ทั้งหมดได้รับการรับรองไว้ในมาตรา 21 โดยการตรวจพิจารณาข่าวสารก่อนเผยแพร่ยังเป็นสิ่งต้องห้ามในญี่ปุ่นอีกด้วย

- สิทธิของคนงาน : สิทธิและหน้าที่ของคนงานมีบัญญัติไว้ในมาตรา 27 และมาตรา 28 โดยมาตรา 27 วรรค 2 ว่า "มาตรฐานของค่าจ้าง ชั่วโมงทำงาน เวลาพักผ่อน และเงื่อนไขอื่น ๆ สำหรับแรงงาน ให้เป็นไปตามที่กฎหมายบัญญัติ"

- สิทธิในทรัพย์สิน : ได้รับการรับรองภายในหลักการว่าหากไม่ขัดต่อสวัสดิภาพประชาชน มาตรา 30 ยังบัญญัติให้ประชาชนย่อมมีหน้าที่ชำระภาษีตามที่กฎหมายบัญญัติอีกด้วย

- สิทธิในกระบวนการทางกฎหมาย : มาตรา 31 บัญญัติว่า บุคคลไม่ต้องรับโทษทางอาญาเว้นแต่ในกรณีที่มีกฎหมายบัญญัติไว้

- การห้ามการกักขังโดยมิชอบด้วยกฎหมาย : มาตรา 33 บัญญัติว่า "การจับกุมตัวบุคคลจะกระทำมิได้ เว้นแต่ได้กระทำตามหมายศาลที่ได้ระบุความผิดของบุคคลนั้น หรือเป็นการจับกุมชนิดคาหนังคาเขา" และมาตรา 34 รับรองกระบวนการในการออกหมายสั่งให้ส่งตัวผู้ถูกคุมขังมาศาล สิทธิในการได้รับทนายความ และสิทธิในการได้รับคำชี้แจงแสดงเหตุผลที่ถูกจับกุมตัว กับทั้งมาตรา 40 ยังอนุญาตให้ผู้ใดได้รับการล้างมลทินภายหลังถูกจับกุมหรือกักขังย่อมเรียกร้องค่าชดเชยจากรัฐได้ตามที่กฎหมายบัญญัติอีกด้วย

- สิทธิในกระบวนการยุติธรรม : มาตรา 37 บัญญัติว่าการพิพากษาคดีทั่วไปต้องกระทำโดยเปิดเผยและโดยคณะตุลาการที่เที่ยงธรรม ซึ่งผู้ต้องสงสัยหรือจำลัยย่อมได้รับโอกาสอย่างเต็มที่ในอันที่จะขอตรวจสอบพยานทั้งปวงอีกด้วย

- การห้ามการกระทำที่อาจทำให้ตนต้องรับผิดทางอาญา : ซึ่งมีบัญญัติในมาตรา 38

- การประกันสิทธิอย่างอื่น:

- สิทธิในการเข้าชื่อเสนอหรือเรียกร้องสิ่งใด ๆ จากรัฐ (มาตรา 16)

- สิทธิที่จะฟ้องร้องรัฐ (มาตรา 17)

- สิทธิทางความคิดและมโนธรรม (มาตรา 19)

- เสรีภาพทางศาสนา (มาตรา 20)

- เสรีภาพทางวิชาการ (มาตรา 23)

- การห้ามการสมรสที่ผู้สมรสไม่ยินยอม (มาตรา 24)

- สิทธิในการเข้าถึงการศึกษาภาคบังคับโดยปลอดค่าใช้จ่าย (มาตรา 26)

- สิทธิที่จะเข้าถึงกระบวนยุติธรรม(มาตรา 32)

- การห้ามการบุกรุก การตรวจค้น และการตรวจยึด (มาตรา 35)

- การห้ามการลงโทษโดยวิธีทรมานและทารุณโหดร้าย (มาตรา 36)

- การห้ามการมีผลย้อนหลังของกฎหมาย(มาตรา 39)

- การห้ามการฟ้องคดีอาญาซ้ำในความผิดเดียวกัน (มาตรา 39)

บทบัญญัติอื่น[แก้]

- การสละสงคราม : มาตรา 9 วรรคหนึ่ง ของรัฐธรรมนูญแห่งญี่ปุ่น (ฉบับ พ.ศ. 2489) บัญญัติว่า "ชนชาวญี่ปุ่นยอมสละจากสงครามไปตลอดกาลนานโดยให้ถือเป็นสิทธิสูงสุดแห่งชาติ กับทั้งสละจากการคุกคามหรือการใช้กำลังเพื่อแก้ไขข้อพิพาทระหว่างชาติด้วย" ในวรรคถัดมายังบัญญัติว่า "จะไม่มีการธำรงไว้ซึ่งกองทัพบก กองทัพเรือ และกองทัพอากาศ กับทั้งศักยภาพอื่น ๆ ในทางสงคราม ไม่มีการรับรองสิทธิในการเป็นพันธมิตรในสงคราม"

- กฎหมายระหว่างประเทศ : มาตรา 98 วรรคสอง บัญญัติว่า "บรรดาสนธิสัญญาที่ญี่ปุ่นยึดถือและกฎหมายที่นานาชาติยอมรับต้องได้รับการปฏิบัติตามอย่างเคร่งครัด" ซึ่งในประเทศทั่วไปแล้วเป็นอำนาจของฝ่ายนิติบัญญัติที่จะพิจารณาว่าจะให้กฎหมายระหว่างประเทศฉบับใดมีผลใช้บังคับในประเทศตนและให้ใช้บังคับได้เพียงไร แต่ภายในบังคับแห่งมาตรา 98 ดังกล่าว บรรดากฎหมายระหว่างประเทศและสนธิสัญญาที่ญี่ปุ่นให้สัตยาบันก็นับเข้าเป็นกฎหมายฉบับหนึ่งของญี่ปุ่นทันที

Amendments and Revisions[แก้]

The constitution has not been amended once since its 1947 enactment. Article 96 provides that amendments can be made to any part of the constitution. However, a proposed amendment must first be approved by both houses of the Diet, by at least a super majority of two-thirds of each house (rather than just a simple majority). It must then be submitted to a referendum in which it is sufficient for it to be endorsed by a simple majority of votes cast. A successful amendment is finally promulgated by the Emperor, but the monarch cannot veto an amendment.

Some commentators have suggested that the difficulty of the amendment process was favoured by the constitution's American authors from a desire that the fundamentals of the regime they had imposed would be resistant to change. However, among Japanese themselves, any change to the document and to the post-war settlement it embodies is highly controversial. From the 1960s to the 1980s, constitutional revision was rarely debated [2]. In the 1990s, right-leaning and conservative voices broke some taboos [3], for example, when the Yomiuri Shimbun published a suggestion for constitutional revision in 1994 [4]. This period saw a number of right-leaning groups forming to aggressively push for constitutional revision, but also a significant number of organizations and individuals speaking out against revision [5] and in support of "the peace constitution."

The debate has been highly polarized. The most controversial issues are proposed changes to Article 9, the "peace article" and provisions relating to the role of the Emperor. Progressive, left, center-left and peace movement related individuals and organizations, as well as the opposition parties [6], labor [7] and youth groups advocate keeping (and even strengthening) the existing constitution in these areas, while right-leaning, nationalist and/or conservative groups and individuals advocate changes to increase the prestige of the Emperor (though not granting him political powers) and to allow a more aggressive stance of the self-defense force, e.g. by turning it officially into a military. Others areas of the constitution and connected laws discussed for potential revision relate to the status of women, the education system and the system of public corporations (including social welfare, non-profit and religious organizations as well as foundations), and structural reform of the election process, e.g. to allow for direct election of the prime minister [8]. There are countless grassroots groups, associations, NGOs, think tanks, scholars, and politicians speaking out in favor of one or the other side of the issue [9].

In August 2005, the then Japanese Prime Minister, Junichiro Koizumi, proposed an amendment to the constitution in order to increase Japan's Defence Forces' roles in international affairs. A draft of the proposed constitution was released by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) on 22 November, 2005 as part of the fiftieth anniversary of the party's founding. The proposed changes included:

- New wording for the Preamble.

- First paragraph of Article 9, renouncing war, is retained. The second paragraph, forbidding the maintenance of "land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential" is replaced by an Article 9-2 which permits a "defence force", under control of the Prime Minister, which defends the nation and may participate in international activities. This new section uses the term "軍" (gun, army or military), which has been avoided under the current constitution. Also, addition in Article 76 of military courts. Members of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces are currently tried as civilians by civilian courts.

- Modified wording in Article 13, regarding respect for individual rights.

- Changes in Article 20, which gives the state limited permission within "the scope of socially acceptable protocol" or "ethno-cultural practices". Changes Article 89 to permit corresponding state funding of religious institutions.

- Changes to Articles 92 and 95, concerning local self-government and relations between local and national governments.

- Changes to Article 96, reducing the vote requirement for constitutional amendments in the Diet from two thirds to a simple majority. A national referendum would still be required.

This draft fanned the debate, with strong opposition coming even from non-governmental organisations of other countries, as well as established and newly formed grassroots Japanese organisations, such as Save Article 9. Per the current constitution, a proposal for constitutional changes must be passed by a two-thirds vote in the Diet, then be put to a national referendum. However, there was in 2005 no legislation in place for such a referendum.

Koizumi's successor, Shinzo Abe vowed to push aggressively for constitutional revision. A major step toward this was getting legislation passed to allow for a national referendum in April 2007 [10]. However, by that time there was little public support for changing the constitution, with a survey showing 34.5 percent of Japanese not wanting any changes, 44.5 percent wanting no changes to Article 9, and 54.6 percent supporting the current interpretation on self-defense [11]. On the 60th anniversary of the constitution, on May 3, 2007, thousands took to the streets in support of Article 9 [12]. The Chief Cabinet secretary and other top government officials interpreted the survey to mean that the public wants a pacifist Constitution that renounces war, and may need to be better informed about the details of the revision debate [13]. The legislation passed by parliament specifies that a referendum on constitutional reform could take place at the earliest in 2010, and would need approval from a majority of voters.

Human rights guarantees in practice[แก้]

- See also: Human rights in Japan

International bodies such as the United Nations Human Rights Committee, which monitors compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and groups such as Amnesty International have argued that many of the guarantees for individual rights contained in the Japanese constitution have not been effective in practice.[ต้องการอ้างอิง] Such critics have also argued that, contrary to Article 98, and its requirement that international law be treated as part of the domestic law of the state, human rights treaties to which Japan is a party are seldom enforced in Japanese courts.[ต้องการอ้างอิง]

Despite constitutional guarantees of the right to a fair trial, conviction rates in Japan approach 99%. In one study, the conviction rate in contested Japanese trials in 1994 was found to be 98.8%, while the comparable conviction rate in contested United States federal trials in 1994 was 30.9%. This was found to be due to the limited budgets for prosecutors in Japan compared to the United States, leading them to prosecute only the most solid cases. Bias by judges was found not to be a factor.[2]

Article 38 also bans coerced confessions. However, the constitution and criminal procedure law permits: 72 hours of confinement, with limited access to an attorney, before indictment of a suspect arrested by police, and 48 hours if arrested by a prosecutor.[ต้องการอ้างอิง] In spite of Article 36's prohibition of torture and cruel punishments, the unusual form of strict regimentation found in Japanese prisons is widely held to be degrading and inhumane.[ต้องการอ้างอิง]

Notes and references[แก้]

- ↑ John Dower, Embracing Defeat, 1999, pp.374, 375, 383, 384.

- ↑ Ramseyer, J. Mark; Rasmusen, Eric (2001), "Why is the Japanese Conviction Rate So High?" (PDF), Journal of Legal Studies, 30 (1): 53–88

{{citation}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|month=ถูกละเว้น (help)

- Kishimoto, Koichi. Politics in Modern Japan. Tokyo: Japan Echo, 1988. ISBN 4-915226-01-8. Pages 7–21.

- Library of Congress Country Study on Japan

- "新憲法制定推進本部". Liberal Democratic Party website.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|accessmonthday=ถูกละเว้น (help); ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|accessyear=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|access-date=) (help) Web page of the Shin Kenpou Seitei Suishin Honbu, Center to Promote Enactment of a New Constitution, of the Liberal Democratic Party. In Japanese. - Rethinking the Constitution: An Anthology of Japanese Opinion, Uleman, F. (transl), 2008, ISBN 1419641654

- "新憲法草案" (PDF). Liberal Democratic Party's Center to Promote Enactment of a New Constitution website.

{{cite web}}: ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|accessmonthday=ถูกละเว้น (help); ไม่รู้จักพารามิเตอร์|accessyear=ถูกละเว้น แนะนำ (|access-date=) (help) Shin Kenpou Sou-an, Draft New Constitution. As released by the Liberal Democratic Party on November 22, 2005. PDF format, in Japanese.

![]() บทความนี้รวมเอางานสาธารณสมบัติจากประเทศศึกษา หอสมุดรัฐสภา

บทความนี้รวมเอางานสาธารณสมบัติจากประเทศศึกษา หอสมุดรัฐสภา

See also[แก้]

- Constitution

- Judicial review

- Japanese Buddhism

- Shintō

- Bushi-Dō

- United States Constitution (Douglas MacArthur, head of the Occupation, was an American, and so were the authors of the original text of Japan's current constitution)

External links[แก้]

- [ Full text] from official website of the House of Councillors

- Birth of the Constitution of Japan

- Beate Sirota Gordon (Blog about Beate Sirota Gordon and the documentary film "The Gift from Beate")

- Constitutional Revision Research Project of the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University