ผู้ใช้:Phaisit16207/ทดลองเขียน 8

สาธารณรัฐตุรกี Türkiye Cumhuriyeti (ตุรกี) | |

|---|---|

เพลงชาติ:

| |

| |

| เมืองหลวง | อังการา 39°N 35°E / 39°N 35°E |

| เมืองใหญ่สุด | อิสตันบูล 41°1′N 28°57′E / 41.017°N 28.950°E |

| ภาษาราชการ | ภาษาตุรกี |

| การปกครอง | รัฐเดี่ยว ระบบประธานาธิบดี สาธารณรัฐรัฐธรรมนูญ |

| เรเจป ไตยิป แอร์โดอัน | |

| ฟ็วต ออคเตย์ | |

| การสร้างชาติ | |

| 23 เมษายน พ.ศ. 2463 | |

| 19 พฤษภาคม พ.ศ. 2462 | |

| 30 สิงหาคม พ.ศ. 2465 | |

| 24 กรกฎาคม พ.ศ. 2466 | |

| 29 ตุลาคม พ.ศ. 2466 | |

| พื้นที่ | |

• รวม | 783,356 ตารางกิโลเมตร (302,455 ตารางไมล์) (อันดับที่ 36) |

| 2.03 (ณ ปี 2558)[1] | |

| ประชากร | |

• 31 ธันวาคม 2563 ประมาณ | |

| 109[2] ต่อตารางกิโลเมตร (282.3 ต่อตารางไมล์) (อันดับที่ 107) | |

| จีดีพี (อำนาจซื้อ) | 2564 (ประมาณ) |

• รวม | |

• ต่อหัว | |

| จีดีพี (ราคาตลาด) | 2564 (ประมาณ) |

• รวม | |

• ต่อหัว | |

| จีนี (2561) | ปานกลาง · อันดับที่ 56 |

| เอชดีไอ (2562) | สูงมาก · อันดับที่ 54 |

| สกุลเงิน | ลีราใหม่ตุรกี (TRY) |

| เขตเวลา | UTC+2 (EET) |

• ฤดูร้อน (เวลาออมแสง) | EEST |

| รหัสโทรศัพท์ | 90 |

| โดเมนบนสุด | .tr |

ประเทศตุรกี (อังกฤษ: Turkey; ตุรกี: Türkiye ทุรคีเย) มีชื่ออย่างเป็นทางการว่า สาธารณรัฐตุรกี (อังกฤษ: Republic of Turkey; ตุรกี: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti) เป็นสาธารณรัฐระบบรัฐสภาในยูเรเชีย พื้นที่ส่วนใหญ่ตั้งอยู่ในเอเชียตะวันตก โดยมีพื้นที่ส่วนน้อยในอีสเทรซในยุโรปตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ ประเทศตุรกีมีพรมแดนติดต่อกับ 8 ประเทศ ได้แก่ ประเทศซีเรียและอิรักทางใต้ ประเทศอิหร่าน อาร์มีเนียและดินแดนส่วนแยกนาคีชีวันของอาเซอร์ไบจานทางตะวันออก ประเทศจอร์เจียทางตะวันออกเฉียงเหนือ ประเทศบัลแกเรียทางตะวันตกเฉียงเหนือ และประเทศกรีซทางตะวันตก ทะเลดำอยู่ทางเหนือ ทะเลเมดิเตอร์เรเนียนทางใต้ และทะเลอีเจียนทางตะวันตก ช่องแคบบอสฟอรัส ทะเลมาร์มะราและดาร์ดะเนลส์ (รวมกันเป็นช่องแคบตุรกี) แบ่งเขตแดนระหว่างเทรซและอานาโตเลีย และยังแยกทวีปยุโรปกับทวีปเอเชีย ที่ตั้งของตุรกี ณ ทางแพร่งของยุโรปและเอเชียทำให้ตุรกีมีความสำคัญทางภูมิรัฐศาสตร์อย่างยิ่ง[6][7][8]

ประเทศตุรกีมีผู้อยู่อาศัยมาตั้งแต่ยุคหินเก่า มีอารยธรรมอานาโตเลียโบราณต่าง ๆ เอโอเลีย โดเรียและกรีกไอโอเนีย เทรซ อาร์มีเนียและเปอร์เซีย หลังการพิชิตของพระเจ้าอเล็กซานเดอร์มหาราช ดินแดนนี้ถูกทำให้เป็นกรีก เป็นกระบวนการซึ่งสืบต่อมาภายใต้จักรวรรดิโรมันและการเปลี่ยนผ่านสู่จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ เติร์กเซลจุคเริ่มย้ายถิ่นเข้ามาในพื้นที่ในคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 11 เริ่มต้นกระบวนการทำให้เป็นเติร์ก ซึ่งเร่งขึ้นมากหลังเซลจุคชนะไบแซนไทน์ที่ยุทธการที่มันซิเคิร์ต ค.ศ. 1071 รัฐสุลต่านรูมเซลจุคปกครองอานาโตเลียจนมองโกลบุกครองใน ค.ศ. 1243 ซึ่งสลายเป็นเบย์ลิก (beylik) เติร์กเล็ก ๆ หลายแห่ง

ตั้งแต่ปลายคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 13 ออตโตมันรวมอานาโตเลียและสร้างจักรวรรดิซึ่งกินพื้นที่กว้างใหญ่ของยุโรปตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เอเชียตะวันตกและแอฟริกาเหนือ[9] กลายเป็นมหาอำนาจในยูเรเซียและทวีปแอฟริการะหว่างสมัยใหม่ตอนต้น[10] จักรวรรดิเรืองอำนาจถึงขีดสุดระหว่างคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 15 ถึง 17[11] โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งระหว่างรัชกาลสุลต่านสุลัยมานผู้เกรียงไกร หลังการล้อมเวียนนาครั้งที่สองของออตโตมันใน ค.ศ. 1683 และการสิ้นสุดมหาสงครามเติร์กใน ค.ศ. 1699 จักรวรรดิออตโตมันเข้าสู่ระยะเสื่อมอันยาวนาน การปฏิรูปแทนซิมัตในคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 19[12] ซึ่งมุ่งทำให้รัฐออตโตมันทันสมัย[13] ไม่เพียงพอในหลายสาขาและไม่อาจหยุดยั้งการสลายของจักวรรดิได้ จักรวรรดิออตโตมันเข้าร่วมสงครามโลกครั้งที่หนึ่งโดยเข้ากับฝ่ายมหาอำนาจกลางและแพ้ในที่สุด ระหว่างสงคราม รัฐบาลออตโตมันก่อความป่าเถื่อนใหญ่หลวง กรณีการฆ่าล้างเผ่าพันธ์ต่อพลเมืองอาร์มีเนีย อัสซีเรียและกรีกพอนทัส หลังสงคราม ดินแดนและประชาชนกลุ่มใหญ่ซึ่งเดิมประกอบเป็นจักรวรรดิออตโตมันถูกแบ่งเป็นหลายรัฐใหม่ สงครามประกาศอิสรภาพตุรกี (ค.ศ. 1919–22) ซึ่งมุสตาฟา เคมาล อตาเติร์กและเพื่อนร่วมงานของเขาในอานาโตเลียเป็นผู้เริ่ม ส่งผลให้มีการสถาปนาสาธารณรัฐตุรกีสมัยใหม่ใน ค.ศ. 1923 โดยอตาเติร์กเป็นประธานาธิบดีคนแรก[14][15]

แม้จะเป็นประเทศกำลังพัฒนา[16][17] แต่ในปัจจุบันตุรกีถือเป็นประเทศมหาอำนาจในเอเชียตะวันตก และเป็นประเทศอุตสาหกรรมใหม่[18] เศรษฐกิจของประเทศจัดอยู่ในกลุ่มประเทศเศรษฐกิจใหม่และเป็นผู้นำการเติบโตในภูมิภาค[19] เป็นประเทศที่ใหญ่เป็นอันดับที่ 20 ของโลกตามผลิตภัณฑ์มวลรวมในประเทศ และใหญ่เป็นอันดับที่ 11 โดยพีพีพี ตุรกีเป็นสมาชิกของสหประชาชาติ และเป็นสมาชิกรุ่นแรกของ เนโท, กองทุนการเงินระหว่างประเทศ และธนาคารโลก และเป็นสมาชิกผู้ก่อตั้งของ องค์การเพื่อความร่วมมือและการพัฒนาทางเศรษฐกิจ, องค์การว่าด้วยความมั่นคงและความร่วมมือในยุโรป, องค์การความร่วมมือทางเศรษฐกิจในทะเลดำ, องค์การความร่วมมืออิสลาม และ กลุ่ม 20 หลังจากกลายเป็นหนึ่งในสมาชิกรุ่นแรกของสภายุโรปใน ค.ศ. 1950 ตุรกีเข้าร่วมสหภาพศุลกากรของสหภาพยุโรปใน ค.ศ. 1995 และเริ่มการเจรจาภาคยานุวัติกับสหภาพยุโรปใน ค.ศ. 2005

ภูมิศาสตร์[แก้]

ภูมิประเทศ[แก้]

ตุรกีเป็นประเทศสองทวีปที่มีดินแดนอยู่ทั้งในทวีปเอเชียและทวีปยุโรป[20] ตุรกีในฝั่งเอเชียซึ่งครอบคลุมบริเวณส่วนใหญ่ของคาบสมุทรอานาโตเลีย นับเป็นพื้นที่ร้อยละ 97 ของประเทศ และถูกแยกจากตุรกีฝั่งยุโรปด้วยช่องแคบบอสพอรัส ทะเลมาร์มะรา และช่องแคบดาร์ดะเนลส์ (ซึ่งรวมกันเป็นพื้นน้ำที่เชื่อมระหว่างทะเลดำกับทะเลเมดิเตอร์เรเนียน) ตุรกีในฝั่งยุโรปซึ่งตั้งอยู่บนคาบสมุทรบอลข่านมีพื้นที่คิดเป็นร้อยละ 3 ของทั้งประเทศ[21] ดินแดนของตุรกีมีรูปร่างคล้ายสี่เหลี่ยมผืนผ้าที่มีความยาวมากกว่า 1,600 กิโลเมตร และกว้างประมาณ 800 กิโลเมตร [22] ตุรกีมีพื้นที่ (รวมทะเลสาบ) ประมาณ 783,562 ตารางกิโลเมตร[23]

ตุรกีถูกล้อมรอบด้วยทะเลสามด้าน ได้แก่ทะเลอีเจียนทางตะวันตก ทะเลดำทางเหนือ และทะเลเมดิเตอร์เรเนียนทางใต้ นอกจากนี้ ยังมีทะเลมาร์มะราในเขตตะวันตกเฉียงเหนือ[24]

ตุรกีฝั่งเอเชียที่มักเรียกว่าอานาโตเลียหรือเอเชียไมเนอร์ประกอบด้วยที่ราบสูงในตอนกลางของประเทศ อยู่ระหว่างเทือกเขาทะเลดำตะวันออกและเกอรอลูทางตอนเหนือกับเทือกเขาเทารัสทางตอนใต้ และมีที่ราบแคบ ๆ บริเวณชายฝั่ง ทางตะวันออกของตุรกีมีลักษณะเป็นภูเขาและเป็นต้นน้ำของแม่น้ำหลายสายเช่น แม่น้ำยูเฟรติส แม่น้ำไทกริส และแม่น้ำอารัส นอกจากนี้ยังมีทะเลสาบวัน และยอดเขาอารารัด ซึ่งเป็นจุดสูงสุดของตุรกีที่ 5,165 เมตร[24]

สภาพภูมิประเทศที่หลากหลายนั้นเป็นผลมาจากการเคลื่อนไหวของเปลือกโลกที่เกิดขึ้นมาเป็นเวลาหลายพันปี และยังคงปรากฏให้เห็นในปัจจุบันในรูปของแผ่นดินไหวที่เกิดขึ้นบ่อย ๆ และภูเขาไฟระเบิดในบางครั้ง ช่องแคบบอสฟอรัสและช่องแคบดาร์ดะเนลส์ก็เกิดจากแนวแยกของเปลือกโลกที่วางตัวผ่านตุรกีทำให้เกิดทะเลดำขึ้น ทางตอนเหนือของประเทศมีแนวแยกแผ่นดินไหววางตัวในแนวตะวันตกไปยังตะวันออก ซึ่งเป็นสาเหตุของแผ่นดินไหวครั้งใหญ่ในปีพ.ศ. 2542[25]

ภูมิอากาศ[แก้]

ชายฝั่งด้านทะเลเมดิเตอร์เรเนียนมีภูมิอากาศแบบเมดิเตอร์เรเนียน กล่าวคือหน้าร้อนอากาศร้อนและแห้งแล้ง ส่วนหน้าหนาวอากาศอบอุ่นและมีฝนตก เทือกเขาที่ตั้งอยู่ใกล้ชายฝั่งเป็นตัวกั้นทำให้ภูมิอากาศตอนกลางของประเทศเป็นแบบภาคพื้นทวีป ซึ่งมีความแตกต่างระหว่างฤดูอย่างเห็นได้ชัด ฤดูหนาวบริเวณที่ราบสูงตอนกลางหนาวมาก อุณหภูมิลดลงถึง -30 ถึง -40℃ อาจมีหิมะปกคลุมนานถึง 4 เดือนต่อปี

ฝั่งตะวันตกมีอุณหภูมิเฉลี่ยในฤดูหนาวต่ำกว่า 1℃ ฤดูร้อนร้อนและแห้งแล้ง ในตอนกลางวันมีอุณหภูมิสูงกว่า 30℃ ปริมาณหยาดน้ำฟ้าเฉลี่ยต่อปีประมาณ 400 มิลลิเมตร ซึ่งปริมาณจริงแตกต่างกันไปตามระดับความสูง บริเวณที่แห้งแล้งที่สุดคือที่ราบกอนยาและที่ราบมาลาตยาซึ่งมีปริมาณน้ำฝนเฉลี่ยนต่อปีต่ำกว่า 300 มิลลิเมตร เดือนที่มีฝนมากที่สุดคือเดือนพฤษภาคม และเดือนที่แล้งที่สุดคือเดือนกรกฎาคมและสิงหาคม[26]

ประวัติศาสตร์[แก้]

ก่อนสมัยเติร์ก[แก้]

Prehistory of Anatolia and Eastern Thrace[แก้]

คาบสมุทรอนาโตเลีย (หรือที่เรียกว่าเอเชียไมเนอร์) ซึ่งประกอบไปด้วยดินแดนของประเทศตุรกีในปัจจุบันเป็นส่วนใหญ่ เป็นหนึ่งในภูมิภาคที่มีการตั้งถิ่นฐานที่เก่าแก่ที่สุดในโลก มีประชากรชาวอนาโตเลียโบราณจำนวนมากอาศัยอยู่ในอนาโตเลีย ตั้งแต่ยุคหินใหม่จนถึงยุคเฮลเลนิสต์เป็นอย่างน้อย[29] ชนชาติเหล่านี้จำนวนมากพูดภาษาอนาโตเลีย ซึ่งเป็นสาขาหนึ่งของตระกูลภาษาอินโด-ยูโรเปียนที่ใหญ่กว่า[30] and, given the antiquity of the Indo-European Hittite and Luwian languages, some scholars have proposed Anatolia as the hypothetical centre from which the Indo-European languages radiated.[31] The European part of Turkey, called Eastern Thrace, has also been inhabited since at least forty thousand years ago, and is known to have been in the Neolithic era by about 6000 BC.[32]

Göbekli Tepe is the site of the oldest known man-made religious structure, a temple dating to circa 10,000 BC,[27] while Çatalhöyük is a very large Neolithic and Chalcolithic settlement in southern Anatolia, which existed from approximately 7500 BC to 5700 BC. It is the largest and best-preserved Neolithic site found to date and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[33] The settlement of Troy started in the Neolithic Age and continued into the Iron Age.[34]

The earliest recorded inhabitants of Anatolia were the Hattians and Hurrians, non-Indo-European peoples who inhabited central and eastern Anatolia, respectively, as early as c. 2300 BC. Indo-European Hittites came to Anatolia and gradually absorbed the Hattians and Hurrians c. 2000–1700 BC. The first major empire in the area was founded by the Hittites, from the 18th through the 13th century BC. The Assyrians conquered and settled parts of southeastern Turkey as early as 1950 BC until the year 612 BC,[35] although they have remained a minority in the region, namely in Hakkari, Şırnak and Mardin.[36]

Urartu re-emerged in Assyrian inscriptions in the 9th century BC as a powerful northern rival of Assyria.[37] Following the collapse of the Hittite empire c. 1180 BC, the Phrygians, an Indo-European people, achieved ascendancy in Anatolia until their kingdom was destroyed by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BC.[38] Starting from 714 BC, Urartu shared the same fate and dissolved in 590 BC,[39] when it was conquered by the Medes. The most powerful of Phrygia's successor states were Lydia, Caria and Lycia.

Antiquity[แก้]

Starting around 1200 BC, the coast of Anatolia was heavily settled by Aeolian and Ionian Greeks. Numerous important cities were founded by these colonists, such as Miletus, Ephesus, Smyrna (now İzmir) and Byzantium (now Istanbul), the latter founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 657 BC.[44] The first state that was called Armenia by neighbouring peoples was the state of the Armenian Orontid dynasty, which included parts of eastern Turkey beginning in the 6th century BC. In Northwest Turkey, the most significant tribal group in Thrace was the Odyrisians, founded by Teres I.[45]

All of modern-day Turkey was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire during the 6th century BC.[46] The Greco-Persian Wars started when the Greek city states on the coast of Anatolia rebelled against Persian rule in 499 BC. The territory of Turkey later fell to Alexander the Great in 334 BC,[47] which led to increasing cultural homogeneity and Hellenization in the area.[29]

Following Alexander's death in 323 BC, Anatolia was subsequently divided into a number of small Hellenistic kingdoms, all of which became part of the Roman Republic by the mid-1st century BC.[48] The process of Hellenization that began with Alexander's conquest accelerated under Roman rule, and by the early centuries of the Christian Era, the local Anatolian languages and cultures had become extinct, being largely replaced by ancient Greek language and culture.[49][50] From the 1st century BC up to the 3rd century CE, large parts of modern-day Turkey were contested between the Romans and neighbouring Parthians through the frequent Roman-Parthian Wars.

Early Christian and Byzantine period[แก้]

According to the Acts of Apostles,[52] Antioch (now Antakya), a city in southern Turkey, is where followers of Jesus were first called "Christians" and became very quickly an important center of Christianity.[53][54]

In 324, Constantine I chose Byzantium to be the new capital of the Roman Empire, renaming it New Rome. Following the death of Theodosius I in 395 and the permanent division of the Roman Empire between his two sons, the city, which would popularly come to be known as Constantinople, became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. This empire, which would later be branded by historians as the Byzantine Empire, ruled most of the territory of present-day Turkey until the Late Middle Ages;[55] although the eastern regions remained firmly in Sasanian hands until the first half of the 7th century CE. The frequent Byzantine-Sassanid Wars, a continuation of the centuries-long Roman-Persian Wars, took place in various parts of present-day Turkey between the 4th and 7th centuries CE.

Several ecumenical councils of the early Church were held in cities located in present-day Turkey including the First Council of Nicaea (Iznik) in 325, the First Council of Constantinople (Istanbul) in 381, the Council of Ephesus in 431, and the Council of Chalcedon (Kadıköy) in 451.[56]

Seljuks and the Ottoman Empire[แก้]

The House of Seljuk originated from the Kınık branch of the Oghuz Turks who resided on the periphery of the Muslim world, in the Yabgu Khaganate of the Oğuz confederacy, to the north of the Caspian and Aral Seas, in the 9th century.[57] In the 10th century, the Seljuks started migrating from their ancestral homeland into Persia, which became the administrative core of the Great Seljuk Empire, after its foundation by Tughril.[58]

In the latter half of the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks began penetrating into medieval Armenia and the eastern regions of Anatolia. In 1071, the Seljuks defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert, starting the Turkification process in the area; the Turkish language and Islam were introduced to Armenia and Anatolia, gradually spreading throughout the region. The slow transition from a predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking Anatolia to a predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking one was underway. The Mevlevi Order of dervishes, which was established in Konya during the 13th century by Sufi poet Celaleddin Rumi, played a significant role in the Islamization of the diverse people of Anatolia who had previously been Hellenized.[59][60] Thus, alongside the Turkification of the territory, the culturally Persianized Seljuks set the basis for a Turko-Persian principal culture in Anatolia,[61] which their eventual successors, the Ottomans, would take over.[62][63]

In 1243, the Seljuk armies were defeated by the Mongols at the Battle of Köse Dağ, causing the Seljuk Empire's power to slowly disintegrate. In its wake, one of the Turkish principalities governed by Osman I would evolve over the next 200 years into the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans completed their conquest of the Byzantine Empire by capturing its capital, Constantinople, in 1453: their commander thenceforth being known as Mehmed the Conqueror.

In 1514, Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) successfully expanded the empire's southern and eastern borders by defeating Shah Ismail I of the Safavid dynasty in the Battle of Chaldiran. In 1517, Selim I expanded Ottoman rule into Algeria and Egypt, and created a naval presence in the Red Sea. Subsequently, a contest started between the Ottoman and Portuguese empires to become the dominant sea power in the Indian Ocean, with a number of naval battles in the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf. The Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean was perceived as a threat to the Ottoman monopoly over the ancient trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe. Despite the increasingly prominent European presence, the Ottoman Empire's trade with the east continued to flourish until the second half of the 18th century.[66]

The Ottoman Empire's power and prestige peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, who personally instituted major legislative changes relating to society, education, taxation and criminal law.

The empire was often at odds with the Holy Roman Empire in its steady advance towards Central Europe through the Balkans and the southern part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[67]

The Ottoman Navy contended with several Holy Leagues, such as those in 1538, 1571, 1684 and 1717 (composed primarily of Habsburg Spain, the Republic of Genoa, the Republic of Venice, the Knights of St. John, the Papal States, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Duchy of Savoy), for the control of the Mediterranean Sea.

In the east, the Ottomans were often at war with Safavid Persia over conflicts stemming from territorial disputes or religious differences between the 16th and 18th centuries.[68] The Ottoman wars with Persia continued as the Zand, Afsharid, and Qajar dynasties succeeded the Safavids in Iran, until the first half of the 19th century.

Even further east, there was an extension of the Habsburg-Ottoman conflict, in that the Ottomans also had to send soldiers to their farthest and easternmost vassal and territory, the Aceh Sultanate[69][70] in Southeast Asia, to defend it from European colonizers as well as the Latino invaders who had crossed from Latin America and had Christianized the formerly Muslim-dominated Philippines.[71]

From the 16th to the early 20th centuries, the Ottoman Empire also fought twelve wars with the Russian Tsardom and Empire. These were initially about Ottoman territorial expansion and consolidation in southeastern and eastern Europe; but starting from the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), they became more about the survival of the Ottoman Empire, which had begun to lose its strategic territories on the northern Black Sea coast to the advancing Russians.

From the second half of the 18th century onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to decline. The Tanzimat reforms, initiated by Mahmud II just before his death in 1839, aimed to modernise the Ottoman state in line with the progress that had been made in Western Europe. The efforts of Midhat Pasha during the late Tanzimat era led the Ottoman constitutional movement of 1876, which introduced the First Constitutional Era, but these efforts proved to be inadequate in most fields, and failed to stop the dissolution of the empire.[72]

As the empire gradually shrank in size, military power and wealth; especially after the Ottoman economic crisis and default in 1875[73] which led to uprisings in the Balkan provinces that culminated in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878); many Balkan Muslims migrated to the Empire's heartland in Anatolia,[74][75] along with the Circassians fleeing the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. The decline of the Ottoman Empire led to a rise in nationalist sentiment among its various subject peoples, leading to increased ethnic tensions which occasionally burst into violence, such as the Hamidian massacres of Armenians.[76]

The loss of Rumelia (Ottoman territories in Europe) with the First Balkan War (1912–1913) was followed by the arrival of millions of Muslim refugees (muhacir) to Istanbul and Anatolia.[78] Historically, the Rumelia Eyalet and Anatolia Eyalet had formed the administrative core of the Ottoman Empire, with their governors titled Beylerbeyi participating in the Sultan's Divan, so the loss of all Balkan provinces beyond the Midye-Enez border line according to the London Conference of 1912–13 and the Treaty of London (1913) was a major shock for the Ottoman society and led to the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état. In the Second Balkan War (1913) the Ottomans managed to recover their former capital Edirne (Adrianople) and its surrounding areas in East Thrace, which was formalised with the Treaty of Constantinople (1913). The 1913 coup d'état effectively put the country under the control of the Three Pashas, making sultans Mehmed V and Mehmed VI largely symbolic figureheads with no real political power.

The Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated. The Ottomans successfully defended the Dardanelles strait during the Gallipoli campaign (1915–1916) and achieved initial victories against British forces in the first two years of the Mesopotamian campaign, such as the Siege of Kut (1915–1916); but the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) turned the tide against the Ottomans in the Middle East. In the Caucasus campaign, however, the Russian forces had the upper hand from the beginning, especially after the Battle of Sarikamish (1914–1915). Russian forces advanced into northeastern Anatolia and controlled the major cities there until retreating from World War I with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk following the Russian Revolution (1917). During the war, the empire's Armenians were deported to Syria as part of the Armenian genocide. As a result, an estimated 600,000[79] to more than 1 million,[79] or up to 1.5 million[80][81][82] Armenians were killed. The Turkish government has refused to acknowledge the events as genocide and states that Armenians were only relocated from the eastern war zone.[83] Genocidal campaigns were also committed against the empire's other minority groups such as the Assyrians and Greeks.[84][85][86] Following the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October 1918, the victorious Allied Powers sought to partition the Ottoman state through the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres.[87]

Republic of Turkey[แก้]

The occupation of Istanbul (1918) and İzmir (1919) by the Allies in the aftermath of World War I prompted the establishment of the Turkish National Movement. Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Pasha, a military commander who had distinguished himself during the Battle of Gallipoli, the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923) was waged with the aim of revoking the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920).[88]

By 18 September 1922 the Greek, Armenian and French armies had been expelled,[89] and the Turkish Provisional Government in Ankara, which had declared itself the legitimate government of the country on 23 April 1920, started to formalise the legal transition from the old Ottoman into the new Republican political system. On 1 November 1922, the Turkish Parliament in Ankara formally abolished the Sultanate, thus ending 623 years of monarchical Ottoman rule. The Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923, which superseded the Treaty of Sèvres,[87][88] led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the newly formed "Republic of Turkey" as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire, and the republic was officially proclaimed on 29 October 1923 in Ankara, the country's new capital.[90] The Lausanne Convention stipulated a population exchange between Greece and Turkey, whereby 1.1 million Greeks left Turkey for Greece in exchange for 380,000 Muslims transferred from Greece to Turkey.[91]

Mustafa Kemal became the republic's first President and subsequently introduced many reforms. The reforms aimed to transform the old religion-based and multi-communal Ottoman constitutional monarchy into a Turkish nation state that would be governed as a parliamentary republic under a secular constitution.[93] With the Surname Law of 1934, the Turkish Parliament bestowed upon Mustafa Kemal the honorific surname "Atatürk" (Father Turk).[88]

The Montreux Convention (1936) restored Turkey's control over the Turkish Straits, including the right to militarise the coastlines of the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits and the Sea of Marmara, and to block maritime traffic in wartime.[94]

Following the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, some Kurdish and Zaza tribes, which were feudal (manorial) communities led by chieftains (agha) during the Ottoman period, became discontent about certain aspects of Atatürk's reforms aiming to modernise the country, such as secularism (the Sheikh Said rebellion, 1925)[95] and land reform (the Dersim rebellion, 1937–1938),[96] and staged armed revolts that were put down with military operations.

İsmet İnönü became Turkey's second President following Atatürk's death on 10 November 1938. On 29 June 1939, the Republic of Hatay voted in favour of joining Turkey with a referendum. Turkey remained neutral during most of World War II, but entered the closing stages of the war on the side of the Allies on 23 February 1945. On 26 June 1945, Turkey became a charter member of the United Nations.[97] In the following year, the single-party period in Turkey came to an end, with the first multiparty elections in 1946. In 1950 Turkey became a member of the Council of Europe.

The Democratic Party established by Celâl Bayar won the 1950, 1954 and 1957 general elections and stayed in power for a decade, with Adnan Menderes as the Prime Minister and Bayar as the President. After fighting as part of the United Nations forces in the Korean War, Turkey joined NATO in 1952, becoming a bulwark against Soviet expansion into the Mediterranean. Turkey subsequently became a founding member of the OECD in 1961, and an associate member of the EEC in 1963.[98]

The country's tumultuous transition to multiparty democracy was interrupted by military coups d'état in 1960 and 1980, as well as by military memorandums in 1971 and 1997.[99][100] Between 1960 and the end of the 20th century, the prominent leaders in Turkish politics who achieved multiple election victories were Süleyman Demirel, Bülent Ecevit and Turgut Özal.

Following a decade of Cypriot intercommunal violence and the coup in Cyprus on 15 July 1974 staged by the EOKA B paramilitary organisation, which overthrew President Makarios and installed the pro-Enosis (union with Greece) Nikos Sampson as dictator, Turkey invaded Cyprus on 20 July 1974 by unilaterally exercising Article IV in the Treaty of Guarantee (1960), but without restoring the status quo ante at the end of the military operation.[101] In 1983 the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which is recognised only by Turkey, was established.[102] The Annan Plan for reunifying the island was supported by the majority of Turkish Cypriots, but rejected by the majority of Greek Cypriots, in separate referendums in 2004. However, negotiations for solving the Cyprus dispute are still ongoing between Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot political leaders.[103]

The conflict between Turkey and the PKK (designated a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the United States,[104] the European Union[105] and NATO[106]) has been active since 1984, primarily in the southeast of the country. More than 40,000 people have died as a result of the conflict.[107][108][109] In 1999 PKK's founder Abdullah Öcalan was arrested and sentenced for terrorism[104][105] and treason charges.[110][111] In the past, various Kurdish groups have unsuccessfully sought separation from Turkey to create an independent Kurdish state, while others have more recently pursued provincial autonomy and greater political and cultural rights for Kurds in Turkey. In the 21st century some reforms have taken place to improve the cultural rights of ethnic minorities in Turkey, such as the establishment of TRT Kurdî, TRT Arabi and TRT Avaz by the TRT.

Since the liberalisation of the Turkish economy in the 1980s, the country has enjoyed stronger economic growth and greater political stability.[112] Turkey applied for full membership of the EEC in 1987, joined the EU Customs Union in 1995 and started accession negotiations with the European Union in 2005.[113][114] In a non-binding vote on 13 March 2019, the European Parliament called on the EU governments to suspend EU accession talks with Turkey, citing violations of human rights and the rule of law; but the negotiations, effectively on hold since 2018, remain active as of 2020.[115]

In 2013, widespread protests erupted in many Turkish provinces, sparked by a plan to demolish Gezi Park but soon growing into general anti-government dissent.[116] On 15 July 2016, an unsuccessful coup attempt tried to oust the government.[117] As a reaction to the failed coup d'état, the government carried out mass purges.[118][119]

Between 9 October – 25 November 2019, Turkey conducted a military offensive into north-eastern Syria.[120][121][122]

การเมืองการปกครอง[แก้]

บริหาร[แก้]

ตุรกีปกครองในรูปแบบสาธารณรัฐประชาธิปไตยแบบประธานาธิบดี นับตั้งแต่การก่อตั้งสาธารณรัฐในปี พ.ศ. 2466 การเป็นรัฐโลกวิสัยเป็นส่วนสำคัญของการเมืองตุรกี ประมุขแห่งรัฐของตุรกีคือประธานาธิบดี ได้รับการเลือกตั้งโดยตรง ดำรงตำแหน่งเป็นเวลาห้าปี ไม่เกินสองสมัยติดต่อกัน

นิติบัญญัติ[แก้]

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

ตุลาการ[แก้]

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

สถานการณ์การเมือง[แก้]

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

สิทธิมนุษยชน[แก้]

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

การแบ่งเขตการปกครอง[แก้]

ตุรกีแบ่งเขตการปกครองออกเป็น 81 จังหวัด (provinces - iller) ได้แก่

|

|

|

ต่างประเทศ[แก้]

กองทัพ[แก้]

กองทัพตุรกี (Turkish Armed Forces-TSK) มีกําลังพล จํานวน 355,200 นาย[123] แบ่งเป็น กองทัพบก 260,200 นาย, กองทัพเรือ 45,000 นาย, กองทัพอากาศ 50,000 นาย และกองกำลังสํารอง 378,700 นาย (2018) งบประมาณด้านการทหารเมื่อปี 2017 เท่ากับ 2.5% ของผลิตภัณฑ์มวลรวมในประเทศ ความพยายามทํารัฐประหารในตุรกีเมื่อ 15 กรกฎาคม 2016 ส่งผลต่อสถานะของกองทัพและนําไปสู่ความพยายามปฏิรูปกองทัพเพื่อลดอํานาจของกองทัพ และเพิ่มอํานาจของพลเรือน

เศรษฐกิจ[แก้]

โครงสร้าง[แก้]

นับตั้งแต่การเป็นสาธารณรัฐ ตุรกีได้มีแนวทางเข้าหาการนิยมอำนาจรัฐ โดยมีการควบคุมจากรัฐบาลในด้านการมีส่วนร่วมของภาคเอกชน การค้าต่างประเทศ และการลงทุนโดยตรงจากต่างประเทศ อย่างไรก็ตาม ในช่วงหลังปี 2526 ตุรกีเริ่มมีการปฏิรูป นำโดยนายกรัฐมนตรีตุรกุต เออซัล ตั้งใจปรับจากเศรษฐกิจแบบอำนาจรัฐเป็นแบบของตลาดและภาคเอกชนมากขึ้น[112] การปฏิรูปนี้ส่งผลให้มีการเจริญเติบโตอย่างรวดเร็ว แต่ก็สะดุดจากภาวะเศรษฐกิจถดถอยและวิกฤติทางการเงินในปี 2537 2542[124] และ 2544[125] เป็นผลให้มีการเจริญเติบโตของจีดีพีเฉลี่ยต่อปีตั้งแต่ปี 2524 ถึง 2546 อยู่ที่ 4 เปอร์เซนต์[126] การขาดหายของการปฏิรูปเพิ่มเติม กอปรกับการขาดดุลงบประมาณของภาครัฐที่เพิ่มขึ้นอย่างมากและคอร์รัปชัน ทำให้เกิดเงินเฟ้อสูง ภาคการธนาคารที่อ่อนแอ และความไม่แน่นอนทางเศรษฐกิจมหภาคที่เพิ่มขึ้น[127]

สถานการณ์สำคัญ[แก้]

นับตั้งแต่วิกฤติเศรษฐกิจปี 2544 และการปฏิรูปที่เริ่มโดยรัฐมนตรีคลังในขณะนั้น เกมัล เดร์วึช อัตราเงินเฟ้อได้ลดลงเหลือเป็นเลขหลักเดียว ความเชื่อมั่นของนักลงทุนและการลงทุนจากต่างประเทศเพิ่มมากขึ้น และการว่างงานลดลง ไอเอ็มเอฟพยากรณ์อัตราเงินเฟ้อในปี 2551 ของตุรกีไว้ที่ 6 เปอร์เซนต์[128] ตุรกีได้พยายามเปิดกว้างระบบตลาดมากขึ้นผ่านการปฏิรูปเศรษฐกิจ โดยลดการควบคุมจากรัฐบาลด้านการค้าต่างประเทศและการลงทุน และการแปรรูปอุตสาหกรรมของรัฐ การเปิดเสรีในหลายด้านไปสู่ภาคเอกชนและต่างประเทศได้ดำเนินต่อไปท่ามกลางการโต้เถียงทางการเมือง[129]

โครงสร้างพื้นฐาน[แก้]

คมนาคม และ โทรคมนาคม[แก้]

วิทยาศาสตร์และเทคโนโลยี[แก้]

พลังงาน[แก้]

การสาธารณสุข[แก้]

การศึกษา[แก้]

การศึกษาในประเทศตุรกีเป็นแบบภาคบังคับ และไม่เก็บค่าเล่าเรียนสำหรับนักเรียนตั้งแต่อายุ 6 ถึง 15 ปี อัตราการรู้หนังสือคือร้อยละ 95.3 ในผู้ชาย ร้อยละ 79.6 ในผู้หญิง และเฉลี่ยรวมร้อยละ 87.4 [130] การที่อัตราการรู้หนังสือของผู้หญิงต่ำกว่าชายป็นเพราะในเขตชนบทยังคงมีแนวความคิดแบบเก่าที่ไม่นิยมให้ผู้หญิงเรียนหนังสือ[131]

ประชากรศาสตร์[แก้]

เมืองใหญ่สุด 20 อันดับแรก[แก้]

เชื้อชาติ[แก้]

ในปี พ.ศ. 2550 ตุรกีมีประชากร 70.5 ล้านคน และมีอัตราการเติบโตร้อยละ 1.04 ต่อปี ความหนาแน่นของประชากรเฉลี่ย 92 คนตารางกิโลเมตร ความหนาแน่นของประชากรในแต่ละจังหวัดแตกต่างกันตั้งแต่ 11 คนต่อตารางกิโลเมตร (ในตุนเจลี) จนถึง 2,420 คนต่อตารางกิโลเมตร (ในอิสตันบูล) ค่ามัธยฐานของอายุประชากรคือ 28.3 [133] จากข้อมูลของทางการในปี พ.ศ. 2548 อายุคาดหมายเฉลี่ยของประชากรทั้งหมดคือ 71.3 ปี[134]

ประชากรส่วนใหญ่ของตุรกีมีเชื้อสายตุรกี ซึ่งมีอยู่ประมาณ 50 ถึง 55 ล้านคน[135] ชนชาติอื่น ๆ ที่สำคัญได้แก่ชาวเคิร์ด, เซอร์ซาสเซียน, ซาซา บอสเนีย, จอร์เจีย, อัลเบเนีย, โรมา (ยิปซี), อาหรับ และอีก 3 ชนชาติที่ได้รับการยอมรับจากทางการได้แก่พวกกรีก, อาร์มีเนีย และยิว ในบรรดาชนชาติเหล่านี้ กลุ่มที่ใหญ่ที่สุดคือชาวเคิร์ด (ประมาณ 12.5 ล้านคน[135]) ซึ่งมักจะอาศัยอยู่ทางตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ของประเทศ

หลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 ชาวตุรกีจำนวนมากอพยพไปยังยุโรปตะวันตก (โดยเฉพาะเยอรมนีตะวันตก) เนื่องจากความต้องการแรงงานในยุโรปเพิ่มขึ้น ทำให้เกิดชุมชนชาวตุรกีนอกประเทศขึ้น แต่ในระยะหลังตุรกีกลับกลายเป็นจุดหมายของผู้อพยพจากประเทศข้างเคียง ซึ่งมีทั้งผู้อพยพที่ปักหลักอยู่ในประเทศตุรกี และผู้ที่ใช้ตุรกีเป็นทางผ่านต่อไปยังประเทศกลุ่มยุโรป[136] [137]

ภาษา[แก้]

ประเทศตุรกีมีภาษาทางการเพียงภาษาเดียวคือภาษาตุรกี [138] ซึ่งภาษาตุรกียังเป็นภาษาที่พูดในหลายพื้นที่ในยุโรป เช่นไซปรัส ทางตอนใต้ของคอซอวอ มาเซโดเนีย และพื้นที่ในคาบสมุทรบอลข่านที่เคยเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของจักรวรรดิออตโตมัน เช่น แอลเบเนีย บอสเนียและเฮอร์เซโกวีนา บัลแกเรีย กรีซ โรมาเนีย และเซอร์เบีย[139] นอกจากนี้ ยังมีผู้ที่ใช้ภาษาตุรกีมากกว่า 2 ล้านคนอาศัยอยู่ในเยอรมนี และมีกลุ่มผู้ใช้ภาษาตุรกีในประเทศออสเตรีย เบลเยียม ฝรั่งเศส อิตาลี เนเธอร์แลนด์ สวิตเซอร์แลนด์ และสหราชอาณาจักร[140]

ศาสนา[แก้]

ร้อยละ 99 นับถือศาสนาอิสลาม (31,129,845 คน) ที่เหลือเป็นคริสต์ นิกายอีสเทิร์นออร์โธดอกซ์ (143,251) คริสต์นิกายโรมันคาทอลิก (25,833 คน) คริสต์นิกายโปรเตสแตนต์ (22,983 คน) และยิว (38,267 คน)

กีฬา[แก้]

การแข่งขันระดับนานาชาติ[แก้]

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

ฟุตบอล[แก้]

ฟุตบอลเป็นหนึ่งในกีฬาที่ได้รับความนิยมสูงในประเทศ ตุรกีมีลีกอาชีพที่มีชื่อเสียงคือ ซือเปร์ลีก มีสโมสรชื่อดัง อาทิ กาลาทาซาไร, เฟแนร์บาห์แช, อิสตันบูล บาซัคเซเฮอร์ และเบชิกทัช แม้จะไม่เคยชนะเลิศการแข่งขันรายการใหญ่ แต่ฟุตบอลทีมชาติตุรกีก็มีส่วนร่วมในการแข่งขันรายการสำคัญทั้งฟุตบอลโลก และฟุตบอลชิงแชมป์แห่งชาติยุโรป โดยเคยผ่านเข้าเล่นในรอบสุดท้ายฟุตบอลโลก 2 ครั้ง และมีผลงานที่ดีที่สุดคือการคว้าอันดับสามในฟุตบอลโลก 2002 เอาชนะเกาหลีใต้เจ้าภาพร่วมได้ และผ่านเข้ารอบสุดท้าย ฟุตบอลชิงแชมป์แห่งชาติยุโรป 5 ครั้ง ผลงานดีที่สุดของพวกเขาคือรอบรองชนะเลิศในปี 2008

วอลเลย์บอล[แก้]

ตุรกียังขึ้นชื่อในเรื่องของกีฬาวอลเลย์บอล โดยเฉพาะทีมหญิง วอลเลย์บอลหญิงทีมชาติตุรกี มีส่วนร่วมในการแข่งขันนานาชาติ โดยเข้าร่วมโอลิมปิกฤดูร้อน 2 สมัย และคว้าอันดับ 5 ในโอลิมปิก 2020 เข้าร่วมการแข่งขันชิงแชมป์โลก 4 สมัย คว้าอันดับ 6 ในปี 2010 ปัจจุบันทีมหญิงของตุรกีอยู่ในอันดับ 4 ของโลกตามการจัดอันดับของ เอฟไอวีบี[141] ในขณะที่ทีมชายเคยเข้าร่วมการแข่งขันชิงแชมป์โลก 3 ครั้ง และยังไม่เคยเข้าร่วมโอลิมปิก

วัฒนธรรม[แก้]

รากฐานทางสังคมของตุรกีมีมีลักษณะเป็นครอบครัวแบบขยายที่มีความสัมพันธ์กันทั้งสายเลือดและแต่งงาน โดยยึดถือการสืบทอดทางฝ่ายชาย สมาชิกทุกคนยึดถือปฏิบัติตามหลักศาสนา ผู้ชายทำหน้าที่หัวหน้าครอบครัว ในปัจจุบันมีความพยายามส่งเสริมเรื่องความเท่าเทียมกันระหว่างผู้หญิงและผู้ชาย โดยผู้หญิงสามารถออกไปทำงานนอกบ้านได้ ทั้งในส่วนของรัฐบาลและภาคเอกชน แต่ผู้ชายก็ยังมีความคิดว่าผู้หญิงด้อยกว่าทั้งทางด้านร่างกายและอารมณ์

ศิลปกรรม[แก้]

|

| |

นักดนตรีหญิงน้อยทั้งสอง (ซ้าย) และ นักฝึกเต่า (ขวา) จิตรกรรมของ Osman Hamdi Bey

| ||

โดยทั่วไปในความคิดแบบตะวันตก เป็นที่ยอมรับกันว่าจิตรกรรมแบบตุรกีเริ่มเฟื่องฟูในกลางคริสต์ศตวรรศที่ 19 สถาบันจิตรกรรมแห่งแรกของตุรกีคือมหาวิทยาลัยเทคนิคตุรกี (ในขณะนั้นคือ สถาบันวิศวกรรมศาสตร์กองทัพอิมพีเรียล) ซึ่งเปิดสอนในปี 1793 เพื่อจุดมุ่งหมายเชิงการใช้งานมากกว่า[142] ปลายคริสตืศตวรรษที่ 19 การวาดมนุษย์ตามอย่างตะวันตกเริ่มแพร่หลายโดยเฉพาะกับ Osman Hamdi Bey ลัทธิประทับใจ รวมทั้งศิลปะยุคใหม่เริ่มเข้ามากับ Halil Pasha ศิลปินตุรกียุคใหม่ที่ถูกส่งไปเล่าเรียนในยูโรปเมื่อปี 1926 กลับมาพร้อมกับแนวศิลปะร่วมสมัยทั้ง ฟอวิสซึม คิวบิซึม และ เอ็กซ์เพรชชั่นนิสซึม ต่อมาศิลปินได้รวมกันจัดตั้ง "Group D" ซึ่งประกอบด้วยจิตรกรที่นำโดย Abidin Dino, Cemal Tollu, Fikret Mualla, Fahrünnisa Zeid, Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, Adnan Çoker และ Burhan Doğançay ผู้นำเสนอเทรนด์ใหม่ที่จะคงอยู่ในจิตรกรรมตะวันตกไปอีกสามทศวรรศ นอกจาก Group D แล้วยังมีการเคลื่อนไหวอื่น ๆ อีก เช่น "Yeniler Grubu" (ผู้มาใหม่) ราวปลายทศวรรศ 1930s, "On'lar Grubu" (กลุ่มสิบคน) ในทศวรรศ 1940s, "Yeni Dal Grubu" (กลุ่มสาขาใหม่) ในทศวรรศ 1950s และ "Siyah Kalem Grubu" (กลุ่มปากกาดำ) ในทศวรรศ 1960s[143]

พรมตุรกี เป็นศิลปกรรมท้องถิ่นที่มีมาตั้งแต่ตุรกียุคก่อนอิสลาม ยิ่งผ่านกาลเวลามาเท่าไร พรมตุรกีก็ยิ่งมีการผสมผสานวัฒนธรรมใหม่ ๆ มากขึ้นเท่านั้น สังเกตได้จากกลิ่นอายและงานออกแบบที่มีความเป็นไบแซนไทน์ อนาโตเลีย อาร์เมเนีย ฯลฯ ล้วนทำให้เกิดเอกลักษณ์เฉพาะของแต่ละถิ่น จนกระทั่งหลังศาสนาอิสลามเข้ามาเผยแผ่ พรมตุรกีจึงได้รับอิทธิพลอย่างมากจากศิลปะอิสลาม[144]

จุลจิตรกรรมแบบตุรกี (Turkish miniature) เป็นงานศิลป์ชนิดหนึ่งที่พัฒนามาจากธรรมเนียมจุลจิตรกรรมแบบเปอร์เชีย การวาดลวดลายขนาดจิ๋วซึ่งเรียกว่า taswir หรือ nakish พบในวัฒนธรรมออตโตมัน และเรียกสตูดิโอที่ทำชิ้นงานว่า Nakkashanes[145]โดยทั่วไปแล้วจุลจิตรกรรมหนึ่งภาพอาจต้องใช้จิตรกรมากกว่าหนึ่งคน เพื่อร่างโครงสร้าง จัดองค์ประกอบ ลงสี ตกต่งและเก็บรายละเอียด ยังรวมไปถึงขั้นตอนการเขียนคัลลิกราฟี ก่อนที่จะรวมเข้าเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของหนังสือหรือเอกสารหนึ่งหน้า[146]

การสร้างลวดลายหินอ่อนบนกระดาษแบบตุรกี (Turkish paper marbling) ก็เป็นอีกจิตรกรรมที่เป็นที่นิยมและเป็นที่รู้จัก มักพบใช้ในการตกแต่งขอบกระดาษในหนังสือหรือเอกสาร หรือใช้สร้างแม่ลาย (mortif) "Hartif"[147]

ดนตรี[แก้]

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

อาหาร[แก้]

ชาวตุรกีภูมิใจในอาหารของตนเองมาก อาหารตุรกีนั้นมีอิทธิพลของอาหรับ กรีก ยุโรปตะวันออกและยุโรปผสานอยู่ด้วย แม้ว่าอาหารจำพวกฟาสต์ฟู้ดจะเป็นที่นิยมมากขึ้น แต่อาหารท้องถิ่นแบบดั้งเดิมบังคงเป็นเสน่ห์ดึงดูดผู้คนจากทุกมุมโลกในปัจจุบัน[148][149]

อาหารที่มีชื่อเสียงที่สุดคือ กะบาบ เป็นอาหารประเภทเนื้อสัตว์ปรุงสุกต่างๆ ที่มีต้นกำเนิดมาจากอาหารตะวันออกกลาง มีทั้งที่เป็นเนื้อชิ้นใหญ่ เนื้อหั่นเป็นชิ้นเล็ก ๆ เนื้อแล่เป็นชิ้นบาง และเนื้อบด ส่วนใหญ่ใช้หัวหอมหั่นเป็นเครื่องเคียงนอกเหนือจากผักและวัตถุดิบอื่นๆ หาทานได้ทั่วทุกภูมิภาคของตุรกี

อาหารที่มีชื่อเสียงอื่นๆ ได้แก่ เบยิน ทาวาซึ (สมองแกะทอด) เบอเรค (แป้งม้วนใส่ผักหรือเนยแข็งชิ้นเล็กๆ) คาซึค (แตงกวาและโยเกิร์ตกระเทียม) และสลัดผักต่างๆ รวมถึงซุปตุรกีหรือที่เรียกว่า อิสเคมเบ ซึ่งเป็นซุปเครื่องในใส่กระเทียม

อาหารจานหลักเป็นจำพวกเนื้อปลานั้นค่อนข้างแพงหากไม่ได้อยู่ในฤดูกาลแต่มีรสชาติดี โดยเฉพาะในอิสตันบลูหรือตามแถบชายฝั่ง ปลาที่พบอยู่บ่อยๆในเมนูคือ คิลิช (ปลาดาบ), ไคลคาน (ปลาเทอร์บอต), เลฟเรค (ปลาซีเบส), ปาลามุท (ปลาทูน่า) และลูเฟอ (ปลาบลูฟิช) ส่วนเนื้อนั้นปกติจะเป็นเนื้อลูกแกะ, เนื้อไก่ หรือเนื้อวัวปรุงกับผักต่างๆ นอกจากนี้ยังมีซิสเกบาบีหรือเนื้อเสียบเหล็กย่าง ส่วนเนื้อหมูนั้นหารับประทานได้ตามโรงแรมใหญ่ๆ ฮอลิเดย์ วิลเลจ และร้านขายของชำสำหรับตลาดระดับสูง

สถาปัตยกรรม[แก้]

ประเทศตุรกีเป็นสถานที่ที่มีประวัติศาสตร์ยาวนานกว่า 2,500 ปีก่อนคริสตกาล[150] ความโดดเด่นคือมีสถาปัตยกรรมและศิลปวัฒนธรรมที่ผสมผสานระหว่างศิลปะตะวันออกแบบออตโตมันกับศิลปะตะวันตกแบบกรีก-โรมันได้อย่างลงตัว[151] สถาปัตยกรรมที่ดึงดูดนักท่องเที่ยวมีมากมาย เช่น:[152]

พิพิธภัณฑ์ฮายาโซฟีอา: เป็นสิ่งก่อสร้างสถาปัตยกรรมไบแซนไทน์ที่ยิ่งใหญ่และสวยงามที่สุดในเมืองอิสตันบูล เดิมเคยเป็นโบสถ์ของศาสนาคริสต์นิกายออร์ทอดอกซ์ สร้างโดยจักรพรรดิจัสติเนียนแห่งไบแซนไทน์ ต่อมาใน ค.ศ. 1453 จักรวรรดิออตโตมันมีชัยชนะเหนือจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ สุลต่านเมห์เหม็ดที่ 2 จึงดัดแปลงโบสถ์ให้เป็นสุเหร่าแทน โดยสุเหร่าฮายาโซฟีอาเป็นสุเหร่าหลักของเมืองอิสตันบูลยาวนานกว่า 500 ปี ก่อนรัฐบาลตุรกีจะดัดแปลงให้เป็นพิพิธภัณฑ์ใน ค.ศ. 1935 ความโดดเด่นของที่นี่คือยอดโดมขนาดใหญ่และความงดงามของสถาปัตยกรรมการตกแต่งที่ผสมผสานระหว่างศิลปะไบแซนไทน์กับศิลปะออตโตมันเข้าด้วยกัน

สุเหร่าสุลต่านอาห์เหม็ดที่ 1 หรือสุเหร่าสีน้ำเงิน: ตั้งอยู่ตรงข้ามกับพิพิธภัณฑ์ฮาเกียโซเฟีย เริ่มก่อสร้างใน ค.ศ. 1609 เนื่องจากสุลต่านอาห์เหม็ดที่ 1 ต้องการสร้างสุเหร่าศิลปะตะวันออกแบบออตโตมันให้ใหญ่กว่าโบสถ์ฮาเกียโซเฟีย โดยสร้างหันหน้าเข้าหากันแต่อยู่คนละฝั่งเพื่อประชันความยิ่งใหญ่และสวยงาม เอกลักษณ์ของสุเหร่าแห่งนี้คือด้านในสุเหร่าประดับด้วยกระเบื้องสีฟ้าทั้งหมดยามต้องแสงจึงสวยงามมาก ทั้งยังมีลานด้านหน้าที่กว้างที่สุดในกลุ่มสุเหร่าแบบออตโตมันและมีหอสวดมนต์อยู่ถึง 7 หอ

Grand Bazaar ตลาดแกรนด์บาซาร์: เป็นตลาดที่เก่าแก่ที่สุดในประเทศตุรกี มีความเป็นมายาวนานกว่า 1,000 ปี นอกจากจะเก่าแก่ที่สุดแล้ว ยังเป็นตลาดในร่มสถาปัตยกรรมแบบออตโตมันที่ใหญ่และเก่าแก่ที่สุดในโลกอีกด้วย ภายในตลาดแกรนด์บาซาร์มีร้านค้ามากกว่า 4,000 ร้าน มีทางเข้ามากกว่า 21 ทาง แบ่งออกเป็นโซนตามประเภทสินค้าชัดเจน สินค้าหลักๆ ที่ขายในนี้คือ เครื่องเงิน พรม สิ่งทอ เสื้อผ้า วัตถุโบราณ ทองคำ และของที่ระลึก

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

วันหยุด[แก้]

ส่วนนี้รอเพิ่มเติมข้อมูล คุณสามารถช่วยเพิ่มข้อมูลส่วนนี้ได้ |

อ้างอิง[แก้]

- ↑ "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 October 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2020". Turkish Statistical Institute. 31 December 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 5 February 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2021". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. สืบค้นเมื่อ 8 April 2021.

- ↑ "Inequality - Income inequality". us.oecd.org. OECD. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 July 2021.

- ↑ "2020 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2020. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 December 2020.

- ↑ "Turkey | Location, Geography, People, Economy, Culture, & History". Encyclopedia Britannica (ภาษาอังกฤษ).

- ↑ Pegasus. "General Information about Turkey: Location, Geography, People, Economy, Culture, & History". www.flypgs.com (ภาษาอังกฤษ).

- ↑ "Turkey". Geography (ภาษาอังกฤษ). 2014-03-25.

- ↑ Goodman, Peter S. (2018-08-18). "The West Hoped for Democracy in Turkey. Erdogan Had Other Ideas". The New York Times (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบอเมริกัน). ISSN 0362-4331. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2021-09-04.

- ↑ Steadman, Sharon R.; McMahon, Gregory (2011-09-15). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE) (ภาษาอังกฤษ). OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2.

- ↑ Howard, Douglas A. (Douglas Arthur) (2001). The history of Turkey. Internet Archive. Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30708-9.

- ↑ Roderic. H. Davison, Essays in Ottoman and Turkish History, 1774-1923 – The Impact of West, Texas 1990, pp. 115-116.

- ↑ https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3258667.pdf.bannered.pdf

- ↑ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Erdogan: Turkey will 'never accept' genocide charges | DW | 04.06.2016". DW.COM (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบบริติช).

- ↑ "Recep Tayyip Erdogan: Turkey's pugnacious president". BBC News (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบบริติช). 2020-10-27. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2021-09-04.

- ↑ "Country Profile - Turkey". www.un.org.

- ↑ Goswami, Urmi. "Turkey bids to change its status from a developed country to a developing one". The Economic Times. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2021-09-04.

- ↑ https://www.giga-hamburg.de/de/404/

- ↑ https://www.mfa.gov.tr/sc_-114_-turkiye-nin-uluslararasi-iklim-degisikligiyle-mucadele-rejimi-hk-sc.en.mfa

- ↑ Sabancı University (2005). "Geography of Turkey". Sabancı University. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-13.

- ↑ "Turkish Odyssey: Turkey". คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2008-05-09. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2008-08-13.

- ↑ "Geography of Turkey". US Library of Congress. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-13.

- ↑ UN Demographic Yearbook, accessed April 16, 2007

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Turkish Ministry of Tourism (2005). "Geography of Turkey". Turkish Ministry of Tourism. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-13.

- ↑ "Brief Seismic History of Turkey". University of South California, Department of Civil Engineering. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2009-03-12. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-26.

- ↑ "Climate of Turkey". Turkish State Meteorological Service. 2006. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2007-01-10. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2008-8-14.

{{cite web}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|accessdate=(help) - ↑ 27.0 27.1 "The World's First Temple". Archaeology magazine. November–December 2008. p. 23.

- ↑ "Hattusha: the Hittite Capital". whc.unesco.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 12 June 2014.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อSteadmanMcMahon20112 - ↑ "The Position of Anatolian" (PDF). คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 5 May 2013. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Balter, Michael (27 February 2004). "Search for the Indo-Europeans: Were Kurgan horsemen or Anatolian farmers responsible for creating and spreading the world's most far-flung language family?". Science. 303 (5662): 1323. doi:10.1126/science.303.5662.1323. PMID 14988549. S2CID 28212584.

- ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อMET - ↑ "Çatalhöyük added to UNESCO World Heritage List". Global Heritage Fund. 3 July 2012. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 17 January 2013. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Troy". worldhistory.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 August 2014.

- ↑ "Ziyaret Tepe – Turkey Archaeological Dig Site". uakron.edu. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Assyrian Identity in Ancient Times And Today'" (PDF). สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Zimansky, Paul. Urartian Material Culture As State Assemblage: An Anomaly in the Archaeology of Empire. p. 103.

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (October 2000). "Anatolia and the Caucasus, 2000–1000 B.C. in Timeline of Art History.". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 10 September 2006. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 December 2006.

- ↑ Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq. p. 314.

- ↑ "History of the Past: World History".

- ↑ Paul Lunde (May–June 1980). "The Seven Wonders". Saudi Aramco World. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2009-10-13. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2009-09-12.

- ↑ Mark Cartwright. "Celsus Library". worldhistory.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 February 2017.

- ↑ "The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus: The Un-Greek Temple and Wonder". worldhistory.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 17 February 2017.

- ↑ "Istanbul". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ D.M. Lewis; John Boardman (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Joseph Roisman, Ian Worthington. "A companion to Ancient Macedonia" John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 1-4443-5163-X pp. 135–138, 343

- ↑ Hooker, Richard (6 June 1999). "Ancient Greece: The Persian Wars". Washington State University, Washington, United States. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 20 November 2010. สืบค้นเมื่อ 22 December 2006.

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (October 2000). "Anatolia and the Caucasus (Asia Minor), 1000 B.C. – 1 A.D. in Timeline of Art History.". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 14 December 2006. สืบค้นเมื่อ 21 December 2006.

- ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อFreedmanMyers20002 - ↑ Theo van den Hout (2011). The Elements of Hittite. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-50178-1. สืบค้นเมื่อ 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Hagia Sophia". Encyclopædia Britannica. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2 February 2017.

- ↑ "Acts 11:26 and when he found him, he brought him back to Antioch. So for a full year they met together with the church and taught large numbers of people. The disciples were first called Christians at Antioch". biblehub.com. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2021-07-14.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Biblica, Vol. I, p. 186 (p. 125 of 612 in online .pdf file).

- ↑ "ANTIOCH - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2021-07-14.

- ↑ Daniel C. Waugh (2004). "Constantinople/Istanbul". University of Washington, Seattle, Washington. สืบค้นเมื่อ 26 December 2006.

- ↑ Maas, Michael (2015). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02175-4.

- ↑ Wink, Andre (1990). Al Hind: The Making of the Indo Islamic World, Vol. 1, Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-90-04-09249-5.

- ↑ "The Seljuk Turks". peter.mackenzie.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 August 2014.

- ↑ Davison, Roderic H. (2013). Essays in Ottoman and Turkish History, 1774–1923: The Impact of the West. University of Texas Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-292-75894-0.

- ↑ Katherine Swynford Lambton, Ann; Lewis, Bernard, บ.ก. (1977). The Cambridge history of Islam (Reprint. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- ↑ Craig S. Davis. "The Middle East For Dummies" ISBN 0-7645-5483-2 p. 66

- ↑ Thomas Spencer Baynes. "The Encyclopædia Britannica: Latest Edition. A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and General Literature, Volume 23". Werner, 1902

- ↑ Emine Fetvacı. "Picturing History at the Ottoman Court" p 18

- ↑ Simons, Marlise (22 August 1993). "Center of Ottoman Power". The New York Times. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 June 2009.

- ↑ "Dolmabahce Palace". dolmabahcepalace.com. สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 August 2014.

- ↑ Faroqhi, Suraiya (1994). "Crisis and Change, 1590–1699". ใน İnalcık, Halil; Donald Quataert (บ.ก.). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-521-57456-3.

- ↑ Stanford J. Shaw (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Kirk, George E. (2008). A Short History of the Middle East. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4437-2568-2.

- ↑ Palabiyik, Hamit, Turkish Public Administration: From Tradition to the Modern Age, (Ankara, 2008), 84.

- ↑ Ismail Hakki Goksoy. Ottoman-Aceh Relations According to the Turkish Sources (PDF). คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 19 January 2008. สืบค้นเมื่อ 7 December 2018.

- ↑ Charles A. Truxillo (2012), Jain Publishing Company, "Crusaders in the Far East: The Moro Wars in the Philippines in the Context of the Ibero-Islamic World War".

- ↑ "Ottoman/Turkish Visions of the Nation, 1860–1950". สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Niall Ferguson (2 January 2008). "An Ottoman warning for indebted America". Financial Times. สืบค้นเมื่อ 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Todorova, Maria (2009). Imagining the Balkans. Oxford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-19-972838-1. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Mann, Michael (2005). The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. Cambridge University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-521-53854-1. สืบค้นเมื่อ 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "Collapse of the Ottoman Empire, 1918–1920". nzhistory.net.nz. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 August 2014.

- ↑ "Why Turkey hasn't forgotten about the First World War". britishcouncil.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 February 2017.

- ↑ Isa Blumi (2013). Ottoman Refugees, 1878-1939: Migration in a Post-Imperial World. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-4725-1536-0.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "Armenian Genocide". Encyclopædia Britannica. สืบค้นเมื่อ 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: Armenian Genocide". University of Michigan. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 November 2010. สืบค้นเมื่อ 15 July 2010.

- ↑ Freedman, Jeri (2009). The Armenian genocide (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Pub. Group. ISBN 978-1-4042-1825-3.

- ↑ Totten, Samuel, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs (eds.) Dictionary of Genocide. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, p. 19. ISBN 0-313-34642-9.

- ↑ Raziye Akkoç (15 October 2015). "ECHR: Why Turkey won't talk about the Armenian genocide". The Daily Telegraph. สืบค้นเมื่อ 28 May 2016.

- ↑ Donald Bloxham (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, And the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-19-927356-0. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Levene, Mark (Winter 1998). "Creating a Modern 'Zone of Genocide': The Impact of Nation- and State-Formation on Eastern Anatolia, 1878–1923". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 12 (3): 393–433. doi:10.1093/hgs/12.3.393.

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall (2007). The War of the World: Twentieth-Century Conflict and the Descent of the West. Penguin Group. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-14-311239-6.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 "The Treaty of Sèvres, 1920". Harold B. Library, Brigham Young University.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 Mango, Andrew (2000). Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. Overlook. p. lxxviii. ISBN 978-1-58567-011-6.

- ↑ Heper, Criss, Metin, Nur Bilge (2009). Historical Dictionary of Turkey. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6281-4.

- ↑ Axiarlis, Evangelia (2014). Political Islam and the Secular State in Turkey: Democracy, Reform and the Justice and Development Party. I.B. Tauris. p. 11.

- ↑ Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-521-00479-4. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Turkey holds first election that allows women to vote". OUPblog. 6 February 2012.

- ↑ Gerhard Bowering; Patricia Crone; Wadad Kadi; Devin J. Stewart; Muhammad Qasim Zaman; Mahan Mirza (2012). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4008-3855-4. สืบค้นเมื่อ 14 August 2013.

Following the revolution, Mustafa Kemal became an important figure in the military ranks of the Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) as a protégé ... Although the sultanate had already been abolished in November 1922, the republic was founded in October 1923. ... ambitious reform programme aimed at the creation of a modern, secular state and the construction of a new identity for its citizens.

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 173, pp. 214–241.

- ↑ Hassan, Mona (10 January 2017). Longing for the Lost Caliphate: A Transregional History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8371-4.

- ↑ Soner Çağaptay (2002). "Reconfiguring the Turkish nation in the 1930s". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 8:2. Yale University. 8 (2): 67–82. doi:10.1080/13537110208428662. S2CID 143855822.

- ↑ "Growth in United Nations membership (1945–2005)". United Nations. 3 July 2006. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 17 January 2016. สืบค้นเมื่อ 30 October 2006.

- ↑ "Members and partners". OECD. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 August 2014.

- ↑ Hale, William Mathew (1994). Turkish Politics and the Military. Routledge. pp. 161, 215, 246. ISBN 978-0-415-02455-6.

- ↑ Arsu, Sebsem (12 April 2012). "Turkish Military Leaders Held for Role in '97 Coup". The New York Times. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 August 2014.

- ↑ Uslu, Nasuh (2003). The Cyprus question as an issue of Turkish foreign policy and Turkish-American relations, 1959–2003. Nova Publishers. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-59033-847-6. สืบค้นเมื่อ 16 August 2011.

- ↑ "Timeline: Cyprus". BBC. 12 December 2006. สืบค้นเมื่อ 25 December 2006.

- ↑ "UN Cyprus Talks". United Nations. สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 February 2017.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 "U.S. Department of State - Bureau of Counterterrorism: Foreign Terrorist Organizations". U.S. Department of State. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 April 2020.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "Council of the European Union: Council Decision (CFSP) 2019/1341 of 8 August 2019 updating the list of persons, groups and entities subject to Articles 2, 3 and 4 of Common Position 2001/931/CFSP on the application of specific measures to combat terrorism". Official Journal of the European Union. สืบค้นเมื่อ 18 April 2020.

- ↑ "PKK". Republic of Turkey: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. สืบค้นเมื่อ 19 April 2020.

- ↑ Timeline: Kurdish militant group PKK's three-decade war with Turkey, Reuters, 21 March 2013

- ↑ Reuters (10 January 2016). "Turkish forces kill 32 Kurdish militants in bloody weekend as conflict escalates". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Turkey's PKK peace plan delayed". BBC. 10 November 2009. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 February 2010.

- ↑ "Ocalan sentenced to death". BBC. 29 June 1999.

- ↑ "Turkey lifts Ocalan death sentence". BBC. 3 October 2002.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Nas, Tevfik F. (1992). Economics and Politics of Turkish Liberalization. Lehigh University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-934223-19-5. อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่สมเหตุสมผล มีนิยามชื่อ "80sLiberalization" หลายครั้งด้วยเนื้อหาต่างกัน - ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อTR_EUChrono - ↑ อ้างอิงผิดพลาด: ป้ายระบุ

<ref>ไม่ถูกต้อง ไม่มีการกำหนดข้อความสำหรับอ้างอิงชื่อbarroso - ↑ "European Parliament votes to suspend Turkey's EU membership bid". www.dw.com. Deutsche Welle. 13 March 2019.

- ↑ Mullen, Jethro; Cullinane, Susannah (4 June 2013). "What's driving unrest and protests in Turkey?". CNN. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 June 2013.

- ↑ Cunningham, Erin; Sly, Liz; Karatas, Zeynep (16 July 2016). "Turkey rounds up thousands of suspected participants in coup attempt". The Washington Post. สืบค้นเมื่อ 17 July 2016.

- ↑ Hansen, Suzy (13 April 2017). "Inside Turkey's Purge". The New York Times. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "Turkey Purge". turkeypurge.com. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "Pence heads to Turkey as Erdogan rejects calls for ceasefire in Syria". Deutsche Welle. 16 October 2019.

- ↑ "Full Text: Memorandum of Understanding between Turkey and Russia on northern Syria". The Defense Post. 22 October 2019.

- ↑ "Turkey not resuming military operation in northeast Syria: security source". Reuters. 25 November 2019 – โดยทาง www.reuters.com.

- ↑ https://www.tsk.tr/HomeEng

- ↑ "Turkish quake hits shaky economy". British Broadcasting Corporation. 1999-08-17. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-12. (อังกฤษ)

- ↑ "'Worst over' for Turkey". British Broadcasting Corporation. 2002-02-04. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-12. (อังกฤษ)

- ↑ World Bank (2005). "Turkey Labor Market Study" (PDF). World Bank. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-10. (อังกฤษ)

- ↑ OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform - Turkey: crucial support for economic recovery : 2002. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2002. ISBN 92-64-19808-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=ไม่มี|last=(help) (อังกฤษ) - ↑ IMF: World Economic Outlook Database, April 2008. Inflation, end of period consumer prices. Data for 2006, 2007 and 2008. (อังกฤษ)

- ↑ Jorn Madslien (2006-11-02). "Robust economy raises Turkey's hopes". British Broadcasting Corporation. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-12. (อังกฤษ)

- ↑ "Population and Development Indicators - Population and education". Turkish Statistical Institute. 2004-10-18. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2008-05-08. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-11.

- ↑ Jonny Dymond (2004-10-18). "Turkish girls in literacy battle". British Broadcasting Corporation. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-11.

- ↑ http://www.citypopulation.de/Turkey-RBC20.html December 2012 address-based calculation of the Turkish Statistical Institute as presented by citypopulation.de

- ↑ "2007 Census,population statistics in 2007". Turkish Statistical Institute. 2008. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2008-08-15.

- ↑ "Life expectancy has increased in 2005 in Turkey". Hürriyet. 2006-12-03. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-09.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 "Türkiyedeki Kürtlerin Sayısı! (Number of Kurds in Turkey!)" (ภาษาตุรกี). Milliyet. 2008-06-06. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2008-08-18.

- ↑ Kirişçi, Kemal (November 2003). "Turkey: A Transformation from Emigration to Immigration". Center for European Studies, Bogaziçi University. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2006-12-26.

- ↑ "http://www.economist.com/world/international/displaystory.cfm?story_id=11921822". The Economist. November 2008. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2008-9-3.

{{cite web}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|accessdate=(help); แหล่งข้อมูลอื่นใน|title= - ↑ "Turkish language" in The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition | Date: 2008

- ↑ "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Report for language code:tur (Turkish)". 2005. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2007-03-18.Gordon, Raymond G., Jr.

- ↑ "The European Turks: Gross Domestic Product, Working Population, Entrepreneurs and Household Data" (PDF). Turkish Industrialists' and Businessmen's Association. 2003. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 2005-12-04. สืบค้นเมื่อ 2007-01-06.

- ↑ https://www.fivb.com/en/volleyball/rankings/seniorworldrankingwomen

- ↑ Antoinette Harri; Allison Ohta (1999). 10th International Congress of Turkish Art. Fondation Max Van Berchem. ISBN 978-2-05-101763-3.

The first military training institutions were the Imperial Army Engineering School (Mühendishane-i Berr-i Hümâyun, 1793) and the Imperial School of Military Sciences (Mekteb-i Ulûm-ı Harbiye-i Şahane, 1834). Both schools taught painting to enable cadets to produce topographic layouts and technical drawings to illustrate landscapes ...

- ↑ ""10'Lar' Grubu", "Yenı Dal Grubu", "Sıyah Kalem Grubu"". turkresmi.com. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 8 September 2006. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 August 2014.

- ↑ Brueggemann, Werner; Boehmer, Harald (1982). Teppiche der Bauern und Nomaden in Anatolien = Carpets of the Peasants and Nomads in Anatolia (1st ed.). Munich: Verlag Kunst und Antiquitäten. pp. 34–39. ISBN 3-921811-20-1.

- ↑ Barry, Michael (2004). Figurative art in medieval Islam and the riddle of Bihzâd of Herât (1465–1535). p. 27. ISBN 978-2-08-030421-6. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 February 2017.

- ↑ "Turkish Miniatures". www.turkishculture.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 February 2017.

- ↑ "The Turkish Art of Marbling (EBRU)". turkishculture.org. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 February 2017.

- ↑ "ตุรกี อาหารของฝากจากตุรกี ทัวร์ตุรกี ข้อมูลตุรกี". www.tripdeedee.com.

- ↑ "Turkish Cuisine: A Complete Guide to Turkish Food & Drinks". istanbulonfood.com (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบอเมริกัน). 2013-05-01EEST14:56:41+03:00.

{{cite web}}: ตรวจสอบค่าวันที่ใน:|date=(help) - ↑ "Turkish Architecture | All About Turkey". www.allaboutturkey.com.

- ↑ จนคุณรู้จักทุกมุมของโลกใบนี้มากขึ้น!, เกี่ยวกับผู้แต่ง Expedia Th เอ็กซ์พีเดียรักการท่องเที่ยวและชื่นชอบที่จะเก็บประสบการณ์ใหม่ๆ มาฝาก เพื่อพาคุณออกไปสำรวจ ค้นหาสถานที่ท่องเที่ยวต่างๆ จากทั่วโลก ทั้งหมดนี้ก็เพื่อให้คุณรู้สึกว่า "โลกใบนี้เล็กนิดเดียว" (2017-09-11). "เยือนอิสตันบูล เที่ยวประเทศตุรกี 8 ที่นี้อย่าได้พลาด". บล็อกเอ็กซ์พีเดีย.

- ↑ "Architectural Styles of Turkey Ottomans to today". Property Turkey (ภาษาอังกฤษ).

แหล่งข้อมูลอื่น[แก้]

- Official website of the Presidency of the Republic of Turkey เก็บถาวร 2010-06-05 ที่ เวย์แบ็กแมชชีน

- Turkey entry at The World Factbook

- Turkey from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Phaisit16207/ทดลองเขียน 8 ที่เว็บไซต์ Curlie

- Turkey profile from the BBC News

- Turkey at Encyclopædia Britannica

Wikimedia Atlas of Turkey

Wikimedia Atlas of Turkey- Turkey's Official Tourism Portal

- Phaisit16207/ทดลองเขียน 8 ที่เว็บไซต์ Curlie

![]() ดูข้อมูลทางภูมิศาสตร์ที่เกี่ยวข้องกับ Phaisit16207/ทดลองเขียน 8 ที่โอเพินสตรีตแมป

ดูข้อมูลทางภูมิศาสตร์ที่เกี่ยวข้องกับ Phaisit16207/ทดลองเขียน 8 ที่โอเพินสตรีตแมป

- Key Development Forecasts for Turkey from International Futures

- รูปภาพเกี่ยวกับPhaisit16207/ทดลองเขียน 8 ที่ฟลิคเกอร์

หมวดหมู่:ประเทศตุรกี ต หมวดหมู่:รัฐและดินแดนที่ก่อตั้งในปี พ.ศ. 2466

นาโปลี[แก้]

นาโปลี | |

|---|---|

| โกมูเนเดนาโปลี Comune di Napoli | |

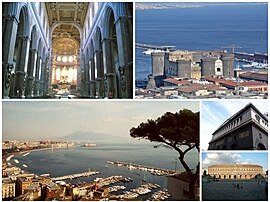

ภาพของนาโปลี ซ้ายบนคือภายในมหาวิหารนาโปลี ขวาบนคือกัสเตลโลนูโอโว ซ้ายล่างคือทิวทัศน์ของท่าเรือ และขวาล่างคือเตอาโตรซานการ์โล | |

| พิกัด: 40°50′N 14°15′E / 40.833°N 14.250°E | |

| ประเทศ | อิตาลี |

| แคว้น | คัมปาเนีย |

| จังหวัด | นาโปลี (NA) |

| การปกครอง | |

| • นายกเทศมนตรี | Luigi de Magistris (DA) |

| พื้นที่ | |

| • ทั้งหมด | 119.02 ตร.กม. (45.95 ตร.ไมล์) |

| ความสูง | 17 เมตร (56 ฟุต) |

| ประชากร (1 มกราคม 2562)[1] | |

| • ทั้งหมด | 3,084,890 คน |

| • ความหนาแน่น | 26,000 คน/ตร.กม. (67,000 คน/ตร.ไมล์) |

| เดมะนิม | Napoletani |

| เขตเวลา | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • ฤดูร้อน (เวลาออมแสง) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| รหัสไปรษณีย์ | 80100, 80121-80147 |

| รหัสเขตโทรศัพท์ | 081 |

| นักบุญองค์อุปถัมภ์ | Januarius |

| วันสมโภชนักบุญ | 19 กันยายน |

| เว็บไซต์ | เว็บไซต์ทางการ |

นาโปลี (อิตาลี: Napoli [ˈnaːpoli] (![]() ฟังเสียง); นาโปลี: Napule [ˈnɑːpələ, ˈnɑːpulə])[a] หรือ เนเปิลส์ (อังกฤษ: Naples /ˈneɪpəlz/) เป็นเมืองหลวงของแคว้นคัมปาเนีย และเป็นเมืองที่ใหญ่ที่สุดเป็นอันดับสามของอิตาลี รองจากโรมและมิลาน โดยมีประชากร 967,069 คน ภายในเขตการปกครองของเมืองเมื่อ ณ ค.ศ. 2017 เขตเทศบาลระดับจังหวัดเป็นนครที่มีประชากรมากที่สุดเป็นอันดับสามในอิตาลีอีกด้วย with a population of 3,115,320 residents, with the its metropolitan area stretching beyond the boundaries of the city wall for approximately 20 miles.

ฟังเสียง); นาโปลี: Napule [ˈnɑːpələ, ˈnɑːpulə])[a] หรือ เนเปิลส์ (อังกฤษ: Naples /ˈneɪpəlz/) เป็นเมืองหลวงของแคว้นคัมปาเนีย และเป็นเมืองที่ใหญ่ที่สุดเป็นอันดับสามของอิตาลี รองจากโรมและมิลาน โดยมีประชากร 967,069 คน ภายในเขตการปกครองของเมืองเมื่อ ณ ค.ศ. 2017 เขตเทศบาลระดับจังหวัดเป็นนครที่มีประชากรมากที่สุดเป็นอันดับสามในอิตาลีอีกด้วย with a population of 3,115,320 residents, with the its metropolitan area stretching beyond the boundaries of the city wall for approximately 20 miles.

Founded by Greeks in the first millennium BC, Naples is one of the oldest continuously inhabited urban areas in the world.[2] In the ninth century BC, a colony known as Parthenope (กรีกโบราณ: Παρθενόπη) was established on the Island of Megaride.[3] In the 6th century BC, it was refounded as Neápolis.[4] The city was an important part of Magna Graecia, played a major role in the merging of Greek and Roman society, and was a significant cultural centre under the Romans.[5]

It served as the capital of the Duchy of Naples (661–1139), then of the Kingdom of Naples (1282–1816), and finally of the Two Sicilies until the unification of Italy in 1861. Naples is also considered a capital of the Baroque, beginning with the artist Caravaggio's career in the 17th century, and the artistic revolution he inspired.[6] It was also an important centre of humanism and Enlightenment.[7][8] The city has long been a global point of reference for classical music and opera through the Neapolitan School.[9] Between 1925 and 1936, Naples was expanded and upgraded by Benito Mussolini's government. During the later years of World War II, it sustained severe damage from Allied bombing as they invaded the peninsula. The city received extensive post-1945 reconstruction work.[10]

Since the late 20th century, Naples has had significant economic growth, helped by the construction of the Centro Direzionale business district and an advanced transportation network, which includes the Alta Velocità high-speed rail link to Rome and Salerno and an expanded subway network. Naples is the third-largest urban economy in Italy, after Milan and Rome.[11] The Port of Naples is one of the most important in Europe. In addition to commercial activities, it is home to the Allied Joint Force Command Naples, the NATO body that oversees North Africa, the Sahel and Middle East.[12]

Naples' historic city centre is the largest of its kind in Europe and has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A wide range of culturally and historically significant sites are nearby, including the Palace of Caserta and the Roman ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Naples is also known for its natural beauties, such as Posillipo, Phlegraean Fields, Nisida, and Vesuvius.[13] Neapolitan cuisine is noted for its association with pizza, which originated in the city, as well as numerous other local dishes. Restaurants in the Naples' area have earned the most stars from the Michelin Guide of any Italian province.[14] Naples' skyline in Centro Direzionale was the first skyline of Italy, built in 1994, and for 15 years it was the only one until 2009. The best-known sports team in Naples is the Serie A football club S.S.C. Napoli, two-time Italian champions who play at the Stadio San Paolo in the southwest of the city, in the Fuorigrotta quarter.

หมายเหตุ[แก้]

อ้างอิง[แก้]

- ↑ ‘City’ population (i.e. that of the comune or municipality) from Popolazione residente al 1° Gennaio 2019 per età, sesso e stato civile, ISTAT.

- ↑ David J. Blackman; Maria Costanza Lentini (2010). Ricoveri per navi militari nei porti del Mediterraneo antico e medievale: atti del Workshop, Ravello, 4–5 novembre 2005. Edipuglia srl. p. 99. ISBN 978-88-7228-565-7.

- ↑ "Greek Naples". naplesldm.com. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 21 March 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 May 2017.

- ↑ Daniela Giampaola, Francesca Longobardo (2000). Naples Greek and Roman. Electa.

- ↑ "Virgil in Naples". naplesldm.com. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 2 April 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 May 2017.

- ↑ Alessandro Giardino (2017), Corporeality and Performativity in Baroque Naples. The Body of Naples. Lexington.

- ↑ "Umanesimo in "Enciclopedia dei ragazzi"". www.treccani.it (ภาษาอิตาลี). สืบค้นเมื่อ 2020-12-28.

- ↑ Musi, Aurelio. Napoli, una capitale e il suo regno (ภาษาอิตาลี). Touring. pp. 118, 156.

- ↑ Florimo, Francesco. Cenno Storico Sulla Scuola Musicale De Napoli (ภาษาอิตาลี). Nabu Press.

- ↑ "Bombing of Naples". naplesldm.com. 7 October 2007. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 27 June 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 9 May 2017.

- ↑ "Sr-m.it" (PDF). คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 8 February 2018.

- ↑ "Napoli, l'inaugurazione dell'Hub di Direzione Strategica della Nato". La Repubblica. 5 September 2017. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิมเมื่อ 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "Rivistameridiana.it" (PDF). คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 26 December 2014.

- ↑ "Quali sono i ristoranti stellati in Italia? Ecco la guida Michelin 2021". Touring Club Itlaiano.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (ลิงก์)