ผู้ใช้:Phaisit16207/ทดลองเขียน 6

| นี่คือหน้าทดลองเขียนของ Phaisit16207 หน้าทดลองเขียนเป็นหน้าย่อยของหน้าผู้ใช้ ซึ่งผู้ใช้มีไว้ทดลองเขียนหรือไว้พัฒนาหน้าต่าง ๆ แต่นี่ไม่ใช่หน้าบทความสารานุกรม ทดลองเขียนได้ที่นี่ หน้าทดลองเขียนอื่น ๆ: หน้าทดลองเขียนหลัก |

จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων, Basileía Rhōmaíōn Imperium Romanum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ค.ศ. 395–1453c | |||||||||

ไคโร (ดูที่ สัญลักษณ์ของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์)

โซลิดัส กำลังพรรณาถึงพระคริสต์ผู้ทรงสรรพานุภาพ ซึ่งได้เป็นบรรทัดฐานของเหรียญในจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์

| |||||||||

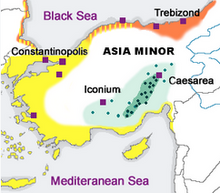

จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ใน ค.ศ. 555 ภายใต้การปกครองของจักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุสที่ 1 ในช่วงที่ยิ่งใหญ่ที่สุด นับตั้งแต่การล่มสลายของจักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันตก (สีชมพูคือรัฐเมืองขึ้น) | |||||||||

การเปลี่ยนแปลงดินแดนของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ (ค.ศ. 476–1400) | |||||||||

| สถานะ | จักรวรรดิ | ||||||||

| เมืองหลวง | คอนสแตนติโนเปิลd (ค.ศ. 395–1204, ค.ศ. 1261–1453) | ||||||||

| ภาษาทั่วไป | |||||||||

| ศาสนา |

| ||||||||

| จักรพรรดิผู้ที่มีชื่อเสียง | |||||||||

• ค.ศ. 306–337 | คอนสแตนตินที่ 1 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 395–408 | อาร์กาดิอุส | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 402–450 | เทออดอซิอุสที่ 2 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 527–565 | ยุสตินิอานุสที่ 1 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 610–641 | เฮราคลิอัส | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 717–741 | ลีโอที่ 3 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 797–802 | ไอเนรีน | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 867–886 | เบซิลที่ 1 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 976–1025 | เบซิลที่ 2 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 1042–1055 | คอนสแตนตินที่ 9 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 1081–1118 | อเล็กซิออสที่ 1 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 1259–1282 | มิคาเอลที่ 8 | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 1449–1453 | คอนสแตนตินที่ 11 | ||||||||

| ยุคประวัติศาสตร์ | ยุคโบราณตอนปลาย ถึง ยุคกลางตอนปลาย | ||||||||

| 1 เมษายน ค.ศ. 286 | |||||||||

| 11 พฤษภาคม ค.ศ. 330 | |||||||||

• การแบ่งจักรวรรดิตะวันออก-ตะวันตกครั้งสุดท้าย ภายหลังการสวรรคตของจักรพรรดิเทออดอซิอุสที่ 1 | 17 มกราคม ค.ศ. 395 | ||||||||

| 4 กันยายน ค.ศ. 476 | |||||||||

• ยูลิอุส แนโปสถูกลอบสังหาร; เป็นจุดจบของจักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันตกในทางทฤษฎี | 25 เมษายน ค.ศ. 480 | ||||||||

• การเข้ายึดครองของมุสลิม; สูญเสียมณฑลที่มั่งคั่งแห่งซีเรียและอียิปต์; อำนาจทางทะเลในเมดิเตอร์เรเนียนสิ้นสุดลง; เป็นจุดเริ่มต้นของยุคมืดของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ | ค.ศ. 622–750 | ||||||||

• สงครามครูเสดครั้งที่ 4; ก่อตั้งจักรวรรดิละติน โดยนักรบครูเสดที่นับถือนิกายคาทอลิก | 12 เมษายน ค.ศ. 1204 | ||||||||

• จักรพรรดิมิคาเอลที่ 8 ยึดกรุงคอนสแตนโนเปิลคืน | 25 กรกฎาคม ค.ศ. 1261 | ||||||||

| 29 พฤษภาคม ค.ศ. 1453 | |||||||||

• การล่มสลายของโมเรีย | 31 พฤษภาคม ค.ศ. 1460 | ||||||||

• การล่มสลายของทราบิซอนด์ | 15 สิงหาคม ค.ศ. 1461 | ||||||||

| ประชากร | |||||||||

• ค.ศ. 457 | 16,000,000 คนe | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 565 | 26,000,000 คน | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 775 | 7,000,000 คน | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 1025 | 12,000,000 คน | ||||||||

• ค.ศ. 1320 | 2,000,000 คน | ||||||||

| สกุลเงิน | โซลิดัส, ดีนาเรียส และไฮเพอร์โพรอน | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์[a] (อังกฤษ: Byzantine Empire) เป็นจักรวรรดิที่สืบทอดโดยตรงจากจักรวรรดิโรมันในปลายสมัยโบราณ และยุคกลาง มีศูนย์กลางอยู่ที่กรุงคอนสแตนติโนเปิล ในบริบทสมัยโบราณตอนปลาย ทั้งคำว่า "จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์" และ "จักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันออก" เป็นคำทางภูมิประวัติศาสตร์ที่สร้างขึ้นและใช้กันในหลายศตวรรษต่อมา ขณะที่พลเมืองยังเรียกจักรวรรดิของตนว่า "จักรวรรดิโรมัน" หรือ "โรมาเนีย" เรื่อยมากระทั่งล่มสลายไป ขณะที่จักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันตกล่มสลายไปในคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 5 ส่วนตะวันออกยังดำเนินต่อมาอีกพันปีก่อนจะเสียแก่เติร์กออตโตมันใน ค.ศ. 1453 ในสมัยที่ยังมีจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ยังคงอยู่นั้น จักรวรรดิเป็นชาติที่มีเศรษฐกิจ วัฒนธรรมและกำลังทหารแข็งแกร่งที่สุดในยุโรป

จากประวัติศาสตร์ส่วนใหญ่ของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ได้แสดงให้เห็นว่าจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์คือจักรวรรดิของชาวกรีก เมื่อคำนึงถึงอิทธิพลของภาษากรีก วัฒนธรรมกรีกและประชากรเชื้อสายกรีก แต่ประชาชนของจักรวรรดิเองนั้น มองจักรวรรดิของตนว่าเป็นเพียงจักรวรรดิโรมันที่มีจักรพรรดิโรมันสืบทอดตำแหน่งอย่างต่อเนื่องกันเท่านั้น[ต้องการอ้างอิง]

การเริ่มต้นของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์นั้นไม่เป็นที่ทราบแน่ชัด โดยส่วนใหญ่ถือว่าจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์เริ่มต้นขึ้นเมื่อจักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินที่ 1 (ครองราชย์ ค.ศ. 306-337) แห่งโรมได้สถาปนานครคอนสแตนติโนเปิลให้เป็น "โรมใหม่" ในปี ค.ศ. 330 และย้ายเมืองหลวงจากโรมมาเป็นคอนสแตนติโนเปิลแทน ดังนั้น จึงถือว่าจักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินเป็นจักรพรรดิองค์แรกของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ไปโดยปริยาย แต่ก็มีบางส่วนถือว่าจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์เริ่มต้นขึ้นในสมัยของธีโอโดเซียสมหาราช (ครองราชย์ ค.ศ. 379-395) ซึ่งคริสต์ศาสนาได้เข้ามาแทนที่ลัทธิเพเกินบูชาเทพเจ้าโรมันในฐานะศาสนาประจำชาติ หรือหลังจากธีโอโดเซียสสวรรคตใน ค.ศ. 395 เมื่อจักรวรรดิโรมันได้แบ่งขั้วการปกครองเป็นฝั่งตะวันออกและตะวันตกอย่างเด็ดขาด ทั้งยังมีบ้างส่วนที่ถือว่าจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์เริ่มต้นขึ้น "อย่างแท้จริง" เมื่อจักรพรรดิโรมูลูส ออกุสตูลูส ซึ่งถือว่าเป็นจักรพรรดิโรมันตะวันตกองค์สุดท้ายถูกปราบดาภิเษก ซึ่งทำให้อำนาจในการปกครองจักรวรรดิตกอยู่ที่ชาวกรีกในฝั่งตะวันออกแต่เพียงฝ่ายเดียว และยังมีอีกบางส่วนที่ถือว่าจักรวรรดิโรมันได้แปลงสภาพเป็นจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์โดยสมบูรณ์ เมื่อจักรพรรดิเฮราคลิอุสเปลี่ยนแปลงชื่อตำแหน่งในราชการ จากเดิมที่เป็นภาษาละติน ให้กลายเป็นภาษากรีกแทน

อย่างไรก็ดี การเปลี่ยนแปลงสถานะของจักรวรรดินั้นเป็นไปอย่างต่อเนื่อง แม้ในช่วงก่อนที่จักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินจะสถาปนานครคอนสแตนติโนเปิลให้เป็นเมืองหลวงใหม่ของจักรวรรดิโรมันใน ค.ศ. 330 ก็ตาม ในตอนนั้นก็ได้มีการแปลงสภาพวัฒนธรรมจากโรมันเป็นกรีก รวมถึงการเปิดรับคริสต์ศาสนาที่เพิ่มขึ้นอย่างต่อเนื่องไปแล้ว

การล่มสลายของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ โดยทั่วไปแล้ว เชื่อว่าเกิดขึ้นหลังจากที่กรุงคอนสแตนติโนเปิลถูกยึดโดยสุลต่านเมห์เหม็ดที่ 2 แห่งจักรวรรดิออตโตมันในปี ค.ศ. 1453 โดยกรุงคอนสแตนติโนเปิลได้ถูกเปลี่ยนชื่อใหม่เป็นอิสตันบูลมาจนถึงปัจจุบัน และในทางประวัติศาสตร์ยังได้ถือว่าการสิ้นสุดของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์เป็นจุดสิ้นสุดยุคกลางในยุโรปอีกด้วย

การเรียกชื่อ[แก้]

การใช้คำว่า "ไบแซนไทน์" เพื่อระบุปีต่อ ๆ มาของจักรวรรดิโรมันเป็นครั้งแรก เกิดขึ้นเมื่อ ค.ศ. 1557 หรือ 104 ปีภายหลังการล่มสลายของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ เมื่อเฮียนามนุส ไวฟ์ นักประวัติศาสตร์ชาวเยอรมัน ได้ตีพิมพ์ผลของเขาที่มีชื่อว่า Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ ซึ่งเป็นแหล่งรวบรวมแหล่งข้อมูลทางประวัติศาสตร์[ต้องการอ้างอิง] ซึ่งคำนี้นำมาจากคำว่า "Byzanium" ซึ่งเป็นชื่อเมืองที่จักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินย้ายเมืองหลวงจากโรม และสร้างขึ้นมาใหม่ภายใต้ชื่อใหม่คือคอนสแตนติโนเปิล ชื่อเก่าของนครนี้จึงไม่ค่อยใช้นับตั้งแต่บัดนี้เป็นต้นไป ยกเว้นในบริบททางประวัติศาสตร์หรือบทกวี Byzantine du Louvre (Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae) ซึ่งเป็นสิ่งตีพิมพ์ใน ค.ศ. 1648 และ Historia Byzantina ของดูกองค์ ใน ค.ศ. 1680 ได้ทำให้การใช้คำว่า "ไบแซนไทน์" เป็นที่นิยมในหมู่นักเขียนชาวฝรั่งเศส เช่น มงแต็สกีเยอ เป็นต้น[2] อย่างไรก็ตาม จนถึงกลางคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 19 คำนี้เริ่มใช้กันโดยทั่วไปในโลกตะวันตก[3]

จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์เป็นที่รู้จักของประชาชนในชื่อ "จักรวรรดิโรมัน" หรือ "จักรวรรดิแห่งชาวโรมัน" (ละติน: Imperium Romanum, Imperium Romanorum; กรีกสมัยกลาง: Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Ἀρχὴ τῶν Ῥωμαίων, อักษรโรมัน: Basileia tōn Rhōmaiōn, Archē tōn Rhōmaiōn) โรมาเนีย (ละติน: Romania; กรีกสมัยกลาง: Ῥωμανία, อักษรโรมัน: Rhōmania)[b] สาธารณรัฐโรมัน (ละติน: Res Publica Romana; กรีกสมัยกลาง: Πολιτεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, อักษรโรมัน: Politeia tōn Rhōmaiōn) หรือ "Rhōmais" (กรีกสมัยกลาง: Ῥωμαΐς) ในภาษากรีก[6] ประชากรเรียกตนเองว่า Romaioi และแม้กระทั่งปลายคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 19 ชาวกรีกมักเรียกตนเองด้วยภาษากรีกสมัยใหม่ว่า Romaiika "Romaic"[7] ภายหลัง ค.ศ. 1204 จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ถูกจำกัดขอบเขตให้อยู่ในมณฑลต่าง ๆ ของกรีกล้วนเป็นส่วนใหญ่ คำว่า 'เฮลเลนส์' ก็ถูกนำมาใช้มากขึ้นแทน[8]

ในขณะที่จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์มีลักษณะหลากหลายเชื้อชาติ ในช่วงของประวัติศาสตร์เป็นส่วนใหญ่[9] และรักษาขนบธรรมเนียบแบบโรมัน-กรีกเอาไว้[10] จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ก็ถูกระบุโดยคนร่วมสมัยทางตะวันตกและทางเหนือ ด้วยรากฐานของกรีกที่เริ่มมีอิทธิพลมากขึ้น[11] แหล่งข้อมูลในยุคกลางตะวันตกยังเรียกจักรวรรดินี้ว่า "จักรวรรดิแห่งชาวกรีก" (ละติน: Imperium Graecorum) และตัวจักรพรรดิเองถูกเรียกว่า Imperator Graecorum (จักรพรรดิแห่งชาวกรีก)[12] คำเหล่านี้ถูกใช้เพื่อแยกจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ออกจากจักรวรรดิโรมันอันศักดิ์สิทธิ์ที่อ้างสิทธิ์ในอิทธิพลของจักรวรรดิโรมันโบราณในด้านตะวันตก[13]

ไม่ต่างกันกับโลกอิสลามและสลาฟ ที่ซึ่งจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ถูกมองว่าเป็นจักรวรรดิที่สืบทอดมาจากจักรวรรดิโรมันอย่างตรงไปตรงมามากกว่า ในโลกอิสลาม จักรวรรดิโรมันเป็นที่รู้จักกันในชื่อ รูม เป็นหลัก[14] ชื่อ มิวเล็ด-อี รูม หรือ "ชาติโรมัน" ถูกใช้จนถึงคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 20 นั่นเพื่อกล่าวถึงประชากรของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ นั่นคือ ชุมชนคริสต์ศาสนิกชนออร์ทอดอกซ์ ภายในจักรวรรดิออตโตมัน

ประวัติศาสตร์[แก้]

ตอนต้น[แก้]

ในช่วงคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 3 กองทัพโรมันสามารถยึดครองดินแดนหลายแห่ง ซึ่งครอบคลุมภูมิภาคเมริเตอร์เรเนียนและบริเวณชายฝั่ง ในยุโรปตะวันตกเฉียงใต้และแอฟริกาเหนือ ซึ่งดินแดนเหล่านี้เป็นที่ตั้งของกลุ่มวัฒนธรรมต่าง ๆ ทั้งประชากรในเมืองและในชนบท โดยทั่วไปแล้ว มณฑลต่าง ๆ ของเมริเตอร์เรเนียนตะวันออก มีลักษณะเป็นชุมชนและเมืองมากกว่าด้านตะวันตก โดยก่อนหน้านี้เคยมีการรวมตัวเป็นหนึ่งภายใต้จักรวรรดิมาเกโดนีอาและตกอยู่ภายใต้อิทธิพลของวัฒนธรรมกรีก[15]

จักรวรรดิตะวันตกยังคงได้รับความเดือดร้อนจากความไม่มั่นคงของคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 3 This distinction between the established Hellenised East and the younger Latinised West persisted and became increasingly important in later centuries, leading to a gradual estrangement of the two worlds.[15]

An early instance of the partition of the Empire into East and West occurred in 293 when Emperor Diocletian created a new administrative system (the tetrarchy), to guarantee security in all endangered regions of his Empire. He associated himself with a co-emperor (Augustus), and each co-emperor then adopted a young colleague given the title of Caesar, to share in their rule and eventually to succeed the senior partner. Each tetrarch was in charge of a part of the Empire. The tetrarchy collapsed, however, in 313 and a few years later Constantine I reunited the two administrative divisions of the Empire as sole Augustus.[16]

ถูกทำให้เป็นคริสต์ศาสนิกชนและการแบ่งจักรวรรดิ[แก้]

ใน ค.ศ. 330 จักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินทรงย้ายพระราชอำนาจของจักรวรรดิโรมัน ไปยังคอนสแตนติโนเปิล ซึ่งพระองค์ได้ก่อตั้งเป็นกรุงโรมแห่งที่สองบนที่ตั้งของเมืองบิแซนเทียม ซึ่งเป็นเมืองที่ตั้งอยู่บนเส้นทางการค้าระหว่างทวีปยุโรปและเอเชีย และระหว่างทะเลเมดิเตอร์เรเนียนและทะเลดำ จักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินทรงแนะนำการเปลี่ยนแปลงที่สำคัญต่อสถาบันการทหาร การเงิน พลเรือน และศาสนาของจักรวรรดิโรมัน ส่วนเรื่องนโยบายเศรษฐกิจของพระองค์ พระองค์ถูกนักวิชาการกล่าวหาว่า "เป็นการคลังที่ไม่คิดไตร่ตรอง" แต่ว่าทองคำโซลิดัสที่พระองค์ได้แนะนำนั้น ก็กลายเป็นสกุลเงินที่มั่นคง ซึ่งเปลี่ยนแปลงเศรษฐกิจและส่งเสริมการพัฒนา[17]

ภายใต้การปกครองของจักรพรรดิคอนสแตนติน ศาสนาคริสต์ยังไม่ได้เป็นศาสนาเอกของจักรวรรดิ แต่ก็มีความพึงพอใจเนื่องจากพระองค์ทรงสนับสนุนศาสนานี้ด้วยอภิสิทธิ์มากมาย จักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินได้กำหนดหลักการที่ว่า จักรพรรดิไม่สามารถจัดการคำถามหรือคำสอนด้วยพระองค์เอง แต่ควรเรียกสภาสงฆ์เพื่อจุดประสงค์นั้น การประชุมสภาซีนอดแห่งอาร์ลและสภาแห่งไนเซียครั้งที่ 1 แสดงได้ถึงความสนพระราชหฤทัยในเอกภาพแห่งคริสต์จักร และแสดงให้เห็นถึงการยืนยันว่าพระองค์เองคือหัวหน้า[18] ความรุ่งโรจน์ของคริสต์ศาสนาก็ถูกขัดจังหวะอยู่ชั่วหนึ่งในการราชาภิเษกของจักรพรรดิจูเลียน ใน ค.ศ. 361 ผู้ซึ่งมีความพยายามอย่างแน่วแน่ที่จะฟื้นฟูลัทธิพหุเทวนิยม ทั่วทั้งจักรวรรดิโรมัน และด้วยเหตุนี้พระองค์จึงได้รับการขนานนามว่า "จูเลียนผู้ละทิ้งศรัทธา" โดยพระคริสตจักร[19] อย่างไรก็ตาม ความพยายามนี้ก็ถูกย้อนกลับเมือจักพรรดิจูเลียนถูกปลงพระชนม์ในการรบ ใน ค.ศ. 363[20]

จักรพรรดิเทออดอซิอุสที่ 1 (ค. 379 – 395) เป็นจักรพรรดิพระองค์สุดท้ายที่ปกครองทั้งฝั่งตะวันออกและตะวันตกของจักรวรรดิ ใน ค.ศ. 391 และ ค.ศ. 392 พระองค์ทรงออกพระราชกฤษฎีกาหลายฉบับที่ห้ามศาสนานอกรีต เทศกาลและการบูชายัญของพวกนอกศาสนาถูกห้าม เช่นเดียวกับการเข้าถึงวิหารหรือสถานที่สักการะของพวกนอกศาสนาทั้งหมด[21] การแข่งขันกีฬาโอลิมปิกครั้งสุดท้ายเชื่อว่าถูกจัดขึ้นใน ค.ศ. 393[22] ใน ค.ศ. 395 จักรพรรดิเทออดอซิอุสที่ 1 ยกมรดกให้ทางราชสำนักร่วมกับพระราชโอรสทั้งสองพระองค์ ได้แก่ จักรพรรดิอาร์กาดิอุสทางฝั่งตะวันออกและจักรพรรดิโฮโนริอัสทางฝั่งตะวันตก โดยแบ่งเขตการปกครองของจักรวรรดิโรมันอีกครั้งหนึ่ง ในคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 5 จักรวรรดิฝั่งตะวันออกรอดพ้นจากความลำบากที่จักรวรรดิฝั่งตะวันตกต้องเผชิญเป็นส่วนใหญ่ อันเนื่องจากวัฒนธรรมชุมชนและเมืองมากขึ้นและทรัพยากรทางการเงินที่เพิ่มมากขึ้น ซึ่งทำให้มันสามารถสงบผู้บุกรุกผ่านการส่งบรรณาการและทหารรับจ้างต่างชาติ ความสำเร็จในครั้งนี้ทำให้ จักรพรรดิเทออดอซิอุสที่ 2 สามารถกลับมาทุ่มเทเวลาให้ก้บประมวลกฎหมายของโรมันใน Codex Theodosianus และได้มีการเสริมสร้างความแข็งแกร่งของกำแพงแห่งคอนสแตนติโนเปิล ซึ่งทำให้เมืองแห่งไม่สามารถถูกโจมตีได้ จนถึง ค.ศ. 1204[23] กำแพงเทออดอซิอุสโดยส่วนใหญ่นั้น ได้รับการอนุรักษ์เอาไว้จนถึงปัจจุบัน[ต้องการอ้างอิง]

เพื่อป้องกันการโจมตีจากชาวฮัน จักรพรรดิเทออดอซิอุสต้องส่งบรรณาการประจำปีอย่างใหญ่หลวงให้อัตติลา มาร์เซียน รัชทายาทของพระองค์ ทรงปฏิเสธที่จะส่งบรรณาการอีกต่อไป แต่อัตติลาได้เบี่ยงเบนความสนใจไปที่จักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันตกแลัว หลังจากอัตติลาสิ้นพระชนม์ใน ค.ศ. 453 จักรวรรดิฮันล่มสลาย และชาวฮันที่เหลืออยู่เป็นจำนวนมาก มักได้รับการว่าจ้างเป็นทหารรับจ้าง ในคอนสแตนติโนเปิล[24]

ความรุ่งเรืองถึงขีดสุดในสมัยจักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุสและราชวงศ์ยุสตินิอานุส[แก้]

ราชวงศ์ยุสตินิอานุสถูกก่อตั้งโดยจักรพรรดิยุสตีนุสที่ 1 ซึ่งถึงแม้ว่าพระองค์จะไม่รู้หนังสือ แต่พระองค์ก็ได้ก้าวขึ้นมาจากยศตำแหน่งของกองทัพ เพื่อมาเป็นจักรพรรดิใน ค.ศ. 518[25] พระองค์ถูกสืบทอดโดยพระราชนัดดาของพระองค์ จักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุสที่ 1 ผู้ที่อาจใช้อำนาจปกครองอย่างมีประสิทธิภาพในรัชสมัยของจักรพรรดิยุสตีนุส[26] เป็นหนึ่งในบุคคลที่สำคัญที่สุดสมัยโบราณตอนปลาย และอาจเป็นจักรพรรดิโรมันพระองค์สุดท้ายที่ตรัสภาษาละติน เป็นภาษาแรก[27] ภายใต้การปกครองของจักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุส ถือเป็นยุคที่แตกต่างออกไป ซึ่งโดดเด่นด้วยความปรารถนา แต่มีเพียงบางส่วนที่ตระหนักถึง renovatio imperii หรือ "การฟื้นฟูจักรวรรดิ" เท่านั้น[28] เทออดอรา พระมเหสี ทรงมีอิทธิพลมากเป็นพิเศษ[29]

ใน ค.ศ. 529 จักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุสได้ทรงแต่งตั้งคณะกรรมาธิการ 10 คน โดยมี จอห์นเดอะกัปปาด็อกเชียนเป็นประธาน เพื่อแก้ไขกฎหมายโรมันและสร้างประมวลกฎหมายและข้อคัดแยกของคณะลูกขุนใหม่ ซึ่งเป็นที่รู้จักกันในชื่อ "Corpus Juris Civilis" หรือ ประชุมกฎหมายยุสตินิอานุส ใน ค.ศ. 534 Corpus ได้รับการปรับปรุงและได้ไปร่วมกับพระราชบัญญัติที่ถูกทรงแผยแพร่โดยจักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุส หลัง ค.ศ. 534 ก่อให้เกิดระบบกฎหมายที่ใช้สำหรับภายในส่วนที่เหลือของยุคไบแซนไทน์เป็นส่วนใหญ่[30] Corpus เป็นรากฐานของกฎหมายแพ่งในหลาย ๆ ประเทศ[31]

ใน ค.ศ. 532 จักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุสได้ทรงลงนามในสนธิสัญญาสันติภาพกับพระเจ้าคอสเราที่ 1 แห่งเปอร์เซีย โดยพยายามที่จะรักษาพรมแดนด้านตะวันออกของจักรวรรดิ โดยตกลงที่จะส่งบรรณาการประจำปีให้จักรวรรดิซาเซเนียน ในปีเดียวกัน พระองค์ทรงรอดชีวิตจากการก่อจลาจลในคอนสแตนติโนเปิล (การจลาจลนิกา) ซึ่งทำให้อำนาจของพระองค์แข็งแกร่งขึ้น แต่ต้องจบลงด้วยการเสียชีวิตของผู้ก่อจลาจล 30,000 ถึง 35,000 ราย ตามพระบรมราชโองการของพระองค์[32] การพิชิตฝั่งตะวันตกเริ่มต้นขึ้นใน ค.ศ. 533 เมื่อจักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุสได้ส่ง เบลีซาริอุส นายพลของพระองค์ ไปยึดมณฑลแอฟริกาเดิมคืนจากแวนดัล ซึ่งได้ควบคุมมาตั้งแต่ ค.ศ. 429 โดยมีเมืองหลวงคือคาร์เธจ[33] ความสำเร็จของพวกเขาได้มาอย่างง่ายดายอย่างน่าประหลาดใจ แต่จนถึง ค.ศ. 548 ชนเผ่าท้องถิ่นที่สำคัญถูกพิชิตลง[34]

ใน ค.ศ. 535 กองทหารขนาดเล็กของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ไปถึงซิซิลี ก็ประสบกับความสำเร็จอย่างง่ายดาย แต่ในไม่ช้าชาวกอทเริ่มต่อต้าน และชัยชนะก็ไม่ได้ปรากฎจนถึง ค.ศ. 540 เมื่อเบลีซาริอุสยึดราเวนนาได้ ภายหลังการล้อมนาโปลีและโรมประสบผลสำเร็จ[35] ใน ค.ศ. 535–536 เทออดาปาดได้ส่ง สมเด็จพระสันตะปาปาอกาเปตุสที่ 1 ไปยังคอนสแตนติโนเปิล เพื่อขอให้ถอนกำลังไบแซนไทน์ ออกจากซิซิลี, ดาเมเทีย และอิตาลี ถึงแม้ว่าสมเด็จพระสันตะปาปาอกาเปตุสที่ 1 ล้มเหลวในภารกิจลงนามสันติภาพกับจักรพรรดิยุสตินิอานุส he succeeded in having the Monophysite Patriarch Anthimus I of Constantinople denounced, despite Empress Theodora's support and protection.[36]

The Ostrogoths captured Rome in 546. Belisarius, who had been sent back to Italy in 544, was eventually recalled to Constantinople in 549.[37] The arrival of the Armenian eunuch Narses in Italy (late 551) with an army of 35,000 men marked another shift in Gothic fortunes. Totila was defeated at the Battle of Taginae and his successor, Teia, was defeated at the Battle of Mons Lactarius (October 552). Despite continuing resistance from a few Gothic garrisons and two subsequent invasions by the Franks and Alemanni, the war for the Italian peninsula was at an end.[38] In 551, Athanagild, a noble from Visigothic Hispania, sought Justinian's help in a rebellion against the king, and the emperor dispatched a force under Liberius, a successful military commander. The empire held on to a small slice of the Iberian Peninsula coast until the reign of Heraclius.[39]

In the east, the Roman–Persian Wars continued until 561 when the envoys of Justinian and Khosrau agreed on a 50-year peace.[40] By the mid-550s, Justinian had won victories in most theatres of operation, with the notable exception of the Balkans, which were subjected to repeated incursions from the Slavs and the Gepids. Tribes of Serbs and Croats were later resettled in the northwestern Balkans, during the reign of Heraclius.[41] Justinian called Belisarius out of retirement and defeated the new Hunnish threat. The strengthening of the Danube fleet caused the Kutrigur Huns to withdraw and they agreed to a treaty that allowed safe passage back across the Danube.[42]

Although polytheism had been suppressed by the state since at least the time of Constantine in the 4th century, traditional Greco-Roman culture was still influential in the Eastern empire in the 6th century.[43] Hellenistic philosophy began to be gradually amalgamated into newer Christian philosophy. Philosophers such as John Philoponus drew on neoplatonic ideas in addition to Christian thought and empiricism. Because of active paganism of its professors, Justinian closed down the Neoplatonic Academy in 529. Other schools continued in Constantinople, Antioch and Alexandria, which were the centres of Justinian's empire.[44] Hymns written by Romanos the Melodist marked the development of the Divine Liturgy, while the architects Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles worked to complete the new Church of the Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, which was designed to replace an older church destroyed during the Nika Revolt. Completed in 537, the Hagia Sophia stands today as one of the major monuments of Byzantine architectural history.[45] During the 6th and 7th centuries, the Empire was struck by a series of epidemics, which greatly devastated the population and contributed to a significant economic decline and a weakening of the Empire.[46] Great bathhouses were built in Byzantine centers such as Constantinople and Antioch.[47]

After Justinian died in 565, his successor, Justin II, refused to pay the large tribute to the Persians. Meanwhile, the Germanic Lombards invaded Italy; by the end of the century, only a third of Italy was in Byzantine hands. Justin's successor, Tiberius II, choosing between his enemies, awarded subsidies to the Avars while taking military action against the Persians. Although Tiberius' general, Maurice, led an effective campaign on the eastern frontier, subsidies failed to restrain the Avars. They captured the Balkan fortress of Sirmium in 582, while the Slavs began to make inroads across the Danube.[48]

Maurice, who meanwhile succeeded Tiberius, intervened in a Persian civil war, placed the legitimate Khosrau II back on the throne, and married his daughter to him. Maurice's treaty with his new brother-in-law enlarged the territories of the Empire to the East and allowed the energetic Emperor to focus on the Balkans. By 602, a series of successful Byzantine campaigns had pushed the Avars and Slavs back across the Danube.[48] However, Maurice's refusal to ransom several thousand captives taken by the Avars, and his order to the troops to winter in the Danube, caused his popularity to plummet. A revolt broke out under an officer named Phocas, who marched the troops back to Constantinople; Maurice and his family were murdered while trying to escape.[49]

จักรวรรดิเสื่อมอำนาจ[แก้]

Early Heraclian dynasty[แก้]

After Maurice's murder by Phocas, Khosrau used the pretext to reconquer the Roman province of Mesopotamia.[50] Phocas, an unpopular ruler invariably described in Byzantine sources as a "tyrant", was the target of a number of Senate-led plots. He was eventually deposed in 610 by Heraclius, who sailed to Constantinople from Carthage with an icon affixed to the prow of his ship.[51]

Following the accession of Heraclius, the Sassanid advance pushed deep into the Levant, occupying Damascus and Jerusalem and removing the True Cross to Ctesiphon.[52] The counter-attack launched by Heraclius took on the character of a holy war, and an acheiropoietos image of Christ was carried as a military standard[53] (similarly, when Constantinople was saved from a combined Avar–Sassanid–Slavic siege in 626, the victory was attributed to the icons of the Virgin that were led in procession by Patriarch Sergius about the walls of the city).[54] In this very siege of Constantinople of the year 626, amidst the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, the combined Avar, Sassanid, and Slavic forces unsuccessfully besieged the Byzantine capital between June and July. After this, the Sassanid army was forced to withdraw to Anatolia. The loss came just after news had reached them of yet another Byzantine victory, where Heraclius's brother Theodore scored well against the Persian general Shahin.[55] Following this, Heraclius led an invasion into Sassanid Mesopotamia once again.

The main Sassanid force was destroyed at Nineveh in 627, and in 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony,[56] as he marched into the Sassanid capital of Ctesiphon, where anarchy and civil war reigned as a result of the enduring war. Eventually, the Persians were obliged to withdraw all armed forces and return Sassanid-ruled Egypt, the Levant and whatever imperial territories of Mesopotamia and Armenia were in Roman hands at the time of an earlier peace treaty in c. 595. The war had exhausted both the Byzantines and Sassanids, however, and left them extremely vulnerable to the Muslim forces that emerged in the following years.[57] The Byzantines suffered a crushing defeat by the Arabs at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636, while Ctesiphon fell in 637.[58]

First Arab siege of Constantinople (674–678) and the theme system[แก้]

The Arabs, now firmly in control of Syria and the Levant, sent frequent raiding parties deep into Asia Minor, and in 674–678 laid siege to Constantinople itself. The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of Greek fire, and a thirty-years' truce was signed between the Empire and the Umayyad Caliphate.[59] However, the Anatolian raids continued unabated, and accelerated the demise of classical urban culture, with the inhabitants of many cities either refortifying much smaller areas within the old city walls or relocating entirely to nearby fortresses.[60] Constantinople itself dropped substantially in size, from 500,000 inhabitants to just 40,000–70,000, and, like other urban centres, it was partly ruralised. The city also lost the free grain shipments in 618, after Egypt fell first to the Persians and then to the Arabs, and public wheat distribution ceased.[61]

The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic institutions was filled by the system called theme, which entailed dividing Asia Minor into "provinces" occupied by distinct armies that assumed civil authority and answered directly to the imperial administration. This system may have had its roots in certain ad hoc measures taken by Heraclius, but over the course of the 7th century it developed into an entirely new system of imperial governance.[62] The massive cultural and institutional restructuring of the Empire consequent on the loss of territory in the 7th century has been said to have caused a decisive break in east Mediterranean Romanness, and that the Byzantine state is subsequently best understood as another successor state rather than a real continuation of the Roman Empire.[63]

Late Heraclian dynasty[แก้]

The withdrawal of large numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Asia Minor, many cities shrank to small fortified settlements.[64] In the 670s, the Bulgars were pushed south of the Danube by the arrival of the Khazars. In 680, Byzantine forces sent to disperse these new settlements were defeated.[65]

In 681, Constantine IV signed a treaty with the Bulgar khan Asparukh, and the new Bulgarian state assumed sovereignty over several Slavic tribes that had previously, at least in name, recognised Byzantine rule.[65] In 687–688, the final Heraclian emperor, Justinian II, led an expedition against the Slavs and Bulgarians, and made significant gains, although the fact that he had to fight his way from Thrace to Macedonia demonstrates the degree to which Byzantine power in the north Balkans had declined.[66]

Justinian II attempted to break the power of the urban aristocracy through severe taxation and the appointment of "outsiders" to administrative posts. He was driven from power in 695, and took shelter first with the Khazars and then with the Bulgarians. In 705, he returned to Constantinople with the armies of the Bulgarian khan Tervel, retook the throne and instituted a reign of terror against his enemies. With his final overthrow in 711, supported once more by the urban aristocracy, the Heraclian dynasty came to an end.[67]

Second Arab siege of Constantinople (717–718) and the Isaurian dynasty[แก้]

In 717 the Umayyad Caliphate launched the siege of Constantinople (717–718) which lasted for one year. However, the combination of Leo III the Isaurian's military genius, the Byzantines' use of Greek Fire, a cold winter in 717–718, and Byzantine diplomacy with the Khan Tervel of Bulgaria resulted in a Byzantine victory. After Leo III turned back the Muslim assault in 718, he addressed himself to the task of reorganising and consolidating the themes in Asia Minor. In 740 a major Byzantine victory took place at the Battle of Akroinon where the Byzantines destroyed the Umayyad army once again.

Leo III the Isaurian's son and successor, Constantine V, won noteworthy victories in northern Syria and also thoroughly undermined Bulgarian strength.[68] In 746, profiting by the unstable conditions in the Umayyad Caliphate, which was falling apart under Marwan II, Constantine V invaded Syria and captured Germanikeia, and the Battle of Keramaia resulted in a major Byzantine naval victory over the Umayyad fleet. Coupled with military defeats on other fronts of the Caliphate and internal instability, Umayyad expansion came to an end.

Religious dispute over iconoclasm[แก้]

The 8th and early 9th centuries were also dominated by controversy and religious division over Iconoclasm, which was the main political issue in the Empire for over a century. Icons (here meaning all forms of religious imagery) were banned by Leo and Constantine from around 730, leading to revolts by iconodules (supporters of icons) throughout the empire. After the efforts of empress Irene, the Second Council of Nicaea met in 787 and affirmed that icons could be venerated but not worshipped. Irene is said to have endeavoured to negotiate a marriage between herself and Charlemagne, but, according to Theophanes the Confessor, the scheme was frustrated by Aetios, one of her favourites.[69]

In the early 9th century, Leo V reintroduced the policy of iconoclasm, but in 843 Empress Theodora restored the veneration of icons with the help of Patriarch Methodios.[70] Iconoclasm played a part in the further alienation of East from West, which worsened during the so-called Photian schism, when Pope Nicholas I challenged the elevation of Photios to the patriarchate.[71]

การรุกรานมุสลิมอาหรับ[แก้]

การรุกรานใหม่กำลังเริ่มเข้ามาสู่จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์อีกครั้งนั้นก็คือ ศาสนาอิสลามที่กำลังเผยแพร่ศาสนาโดยการนำของมุสลิมชาวอาหรับที่มีอำนาจมากขึ้นเรื่อย ๆ ทุกที ค.ศ. 632 กองทัพมุสลิมอาหรับก็สามารถเข้าครอบครองคาบสมุทรอารเบีย แล้วเริ่มรุกรานเข้าสู่ดินแดนจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์และเปอร์เซีย

ต่อจากนั้นก็เริ่มเข้ายึดครองเมืองดามัสกัสในปี ค.ศ. 635 ได้จอร์แดนและซีเรียในปี ค.ศ. 636 ได้เยรูซาเล็มในปี ค.ศ. 638 มุสลิมชาวอาหรับก็เริ่มรุกเข้าอียิปต์ และรุกรานเอเชียไมเนอร์ จักรพรรดิเฮราเคลียของไบแซนไทน์พยายามต่อต้านการรุกรานอย่างเต็มกำลัง จนกระทั่งสิ้นรัชกาลในปี ค.ศ. 641 สถานการณ์ยังคงไม่ดีขึ้น

กลางคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 7 มุสลิมอาหรับได้ดินแดนแอฟริกาตอนเหนือของไบแซนไทน์ไปจนหมด ซึ่งดินแดนเหล่านี้ถือเป็นดินแดนที่สำคัญของจักรวรรดิ เพราะมีประชากรมากที่สุด ชาวเมืองเป็นชุมชนที่มีความรู้มีความก้าวหน้าทางวิชาการและที่สำคัญคือเป็นที่ตั้งของเมืองขนาดใหญ่และสำคัญ เช่น เมืองอเล็กซานเดรีย, เยรูซาเล็ม การสูญเสียครั้งนี้ถือเป็นการสุญเสียครั้งยิ่งใหญ่สำหรับจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ เพราะทำให้ไบแซนไทน์ต้องอ่อนแอลงทั้งด้านกำลังคนและเศรษฐกิจ จนเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของการล่มสลายของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ต่อมา[ต้องการอ้างอิง]

ปัญหาการรุกรานของมุสลิมอาหรับกับไบแซนไทน์ก็ดูเหมือนว่าจะจบลงไปชั่วคราวเมื่อได้พันธมิตร โดยจักรพรรดิลีโอที่ 3 ได้ดำเนินนโยบายเป็นมิตรกับชนเผ่าเติร์กจากเอเชียกลางมาช่วยกันไม่ให้มุสลิมอาหรับและบัลแกเรียที่รุกรานออกห่างกรุงคอนสแตนติโนเปิลได้

สมัยราชวงศ์มาซิโดเนียและการฟื้นตัวของจักรวรรดิ (ค.ศ. 867–1025)[แก้]

ค.ศ. 867–1025 ความสงบชั่วคราวทำให้จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์กลับมารุ่งเรืองอีกครั้งหนึ่ง เพราะจักรวรรดิมีความเจริญรุ่งเรืองขึ้นมา การเมืองภายในสงบ มึการขยายดินแดน เศรษฐกิจก็มั่นคง ความก้าวหน้าด้านศิลปวิทยาการก็เจริญ ด้วยการปกครองของจักรพรรดิที่มาจากราชวงศ์มาซิโดเนีย โดยมีจักรพรรดิที่สำคัญได้แก่ เบซิลที่ 1 และเบซิลที่ 2

แท้จริงตำแหน่งจักรพรรดิของไบแซนไทน์นั้นมาจากการเลือกตั้งทำให้ราชวงศ์มาซิโดเนียสามารถเข้ามาเป็นผู้นำได้ อีกทั้งด้วยผลงานของจักรพรรดิเบซิลที่ 1 ที่สามารถมีชัยชนะต่อกองทัพอาหรับ และสามารถขยายดินแดนไปยุโรปตะวันออก อีกทั้งยังยืนยันในการเป็นจักรวรรดิผู้นำคริสต์ศาสนานิกายออร์ทอดอกซ์ไปเผยแพร่อีกด้วยทำให้พระองค์ได้รับความนิยมอย่างมาก

ช่วงปลายรัชสมัยของจักรพรรดิเบซิลนั้นพระองค์สามารถเป็นพันธมิตรกับบัลแกเรียได้ด้วยนโยบายทางศาสนาแต่ก็กลายเป็นปัญหากับไบแซนไทน์มากกว่าที่เคยมีกับอาหรับ โดยจักรพรรดิเบซิลที่ 2 ได้ทำสงครามอย่างยาวนานกับบัลแกเรียนานหลายปี จนกระทั่งปี ค.ศ. 1018 บัลแกเรียก็พ่ายแพ้และตกเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ ชัยชนะที่มีต่อบัลแกเรียนี้ทำให้ไบแซนไทน์สามารถขยายอาณาเขตในยุโรปตะวันออกไปไกลอีกคือ เซอร์เบีย โครเอเชีย แต่อำนาจของและความรุ่งเรืองของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์เริ่มเสื่อมลงเรื่อย ๆ หลังจากที่จักรพรรดิเบซิลที่ 2 สวรรคตในปี ค.ศ. 1025

หลังจักรพรรดิเบซิลที่ 2 เสด็จสวรรคต พระอนุชาคือ จักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินที่ 8 ได้ขึ้นเป็นจักรพรรดิ พระองค์ไม่มีโอรส จักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินที่ 8 พระองค์ครองอำนาจในระยะสั้น แม้ในเวลาต่อมาพระองค์จะไม่มีพระราชโอรสแต่ก็มีพระองค์มีพระราชธิดา 2 พระองค์เท่านั้นคือ โซอิและธีโอโดรา แต่ประชาชนก็ยังเลือกเอาพระธิดาของพระองค์ให้ขึ้นครองราชย์ เพราะประชาชนส่วนใหญ่เชื่อกันว่าความมั่งคั่งของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์มากจากราชวงศ์มาซิโดเนียเท่านั้น

แม้จะมีจักรพรรดิจากราชวงศ์อื่นขึ้นเป็นจักรพรรดิก็ตามแต่ก็อยู่ได้เพียงระยะสั้นเพราะประชาชนไม่นิยมสุดท้าย โซอิ ได้ขึ้นเป็นจักรพรรดินี ครองราชย์ในช่วง ค.ศ. 1028-1050 พระนางได้เสกสมรสถึง 3 ครั้ง ทำให้พระสวามีทั้งสามได้เป็นองค์จักรพรรดิตามไปด้วย ได้แก่ โรมานุสที่ 3 ได้เป็นจักรพรรดิเมื่อปี ค.ศ. 1028-1034 ไมเคิลที่ 4 ได้เป็นจักรพรรดิเมื่อปี ค.ศ. 1034-1041 และ คอนสแตนตินที่ 9 ได้เป็นจักรพรรดิเมื่อปี ค.ศ. 1042-1055 เมื่อคอนสแตนตินที่ 9 สิ้นพระชนม์ ธีโอโดราก็ได้เป็นจักรพรรดินีองค์ต่อมา กระทั่ง ค.ศ. 1055

ช่วงระยะนี้ คือตั้งแต่ปี ค.ศ. 1025-1081 นั้น นับเป็นช่วงปลายยุคทองของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ ระยะเวลาเพียง 56 ปี มีจักรพรรดิปกครองถึง 13 พระองค์ มีความพยายามที่จะเปลี่ยนราชวงศ์ใหม่เข้ามาปกครองแต่ไม่สำเร็จ กระทั่ง ค.ศ. 1081 อเล็กเซียที่ 1 จากตระกูลคอมเมนุส ก็ทำการสำเร็จ และตระกูลนี้ปกครองต่อมาอีก ตั้งแต่ปี ค.ศ. 1081-1185

การรุกรานของเติร์ก[แก้]

ยุคทองของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ ด้านหนึ่งก็มีผลร้ายเหมือนกัน นั่นคือ ด้วยความมั่งคั่ง และรุ่งเรืองต่อเนื่องยาวนานทำให้ประชาชนหลงใหลและขาดการเตรียมตัว ทำให้จักรวรรดิเริ่มอ่อนแอลง อีกทั้งเกิดความแตกแยกในหมู่ผู้ปกครองและชนชั้นสูงและระหว่างกลุ่มขุนนางทหารกับขุนนางพลเรือน เมื่อเกิดการรุกรานจากศัตรูทำให้ไบแซนไทน์ต้องประสบปัญหาในที่สุด

โดยเฉพาะการรุกรานของชนเผ่าเติร์กหรือเซลจุกเตริร์กในเวลาต่อมากล่าวคือชนเผ่าเติร์กเป็นศัตรูกลุ่มใหม่ที่เริ่มรุกรานจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ในกลางศตวรรษที่ 11 อันที่จริงแล้วเมื่อสมัยจักรพรรดิคอนสแตนตินที่ 7 เคยได้เข้าร่วมกับพวกเติร์กในการต่อต้านการรุกรานของบัลแกเรียมาแล้ว ซึ่งหลังจากนั้นจักรพรรดิทรงอนุญาตให้ชาวเติร์กตั้งถิ่นฐานอยู่ในทางตอนใต้ของแม่น้ำดานูบ และที่สำคัญเหนือไปกว่านั้นชาวไบแซนไทน์เองที่สอนให้ชาวเติร์กให้รบเก่งและมีระบบ

ต่อมาเมื่อเติร์กขยายตัวมากยิ่งขึ้นก็เริ่มรุกรานพื้นที่หลายแห่งของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ ในปี ค.ศ. 1055 เติร์กสามารถชนะเปอร์เซีย หลังจากนั้นพวกเขาก็ยกทัพเข้าแบกแดดและเริ่มสถาปนาตนเองเป็นสุลต่าน พร้อมอ้างตัวเป็นผู้คุ้มครองกาหลิบอับบาสิด และเริ่มขยายอำนาจเข้าสู่อียิปต์และอนาโตเนีย ต่อมา ค.ศ. 1065 เติร์กรุกเข้าอาร์มีเนีย และ ค.ศ. 1067 ก็สามารถขยายอำนาจเข้าสู่อนาโตเลียตอนกลาง

ค.ศ. 1067 ไบแซนไทน์มีจักรพรรดิคือ โรมานุสที่ 4 พระองค์ทรงพ่ายแพ้ต่อกองทัพเติร์กที่สนามรบอาร์มีเนีย และพระองค์ก็ถูกจับเป็นเชลยต่อกองทัพของเติร์กจำเป็นต้องเซ็นสัญญาสงบศึกกับเติร์กก่อนจะได้รับการปล่อยตัว เมื่อจักรพรรดิโรมานุสเดินทางกลับยังคอนสแตนติโนเปิลพระองค์ก็ไม่เป็นที่ยอมรับจนเกิดการแย่งชิงอำนาจขึ้นภายในจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ ทำให้เติร์กส่งกองกำลังมารบกวนจนสามารถยึดไนเซีย อันเป็นเมืองฐานกำลังทหารและเศรษฐกิจของจักรวรรดิ ไม่เพียงเท่านั้นไบแซนไทน์ยังถูกซ้ำเติมอีกชาวนอร์แมน รุกเข้ามายึดอิตาลีทั้งหมดในกลางปี ค.ศ. 1071 โดยเข้ายึดฐานที่มั่นของไบแซนไทน์ในอิตาลีที่เมืองบารีได้ให้อิตาลีทั้งหมดตกอยู่ในใต้อำนาจของนอร์แมนกลายเป็นการปิดฉากอำนาจของไบแซนไทน์ในคาบสมุทรอิตาลีไปด้วย

หลังจากเสียอิทธิพลในฝั่งอิตาลีไปแล้ว ไบแซนไทน์ก็มีอาณาเขตเล็กลงมาก นอกจากนั้นภายในไบแซนไทน์ก็เกิดการแย่งชิงอำนาจกันอย่างไม่สิ้นสุด หลังจากที่แย่งชิงกันอยู่ถึง 4 ปี สุดท้าย อเล็กเซียส คอมมินุส ซึ่งเป็นขุนนางทหารก็ได้เป็นจักรพรรดิเมื่อจักรวรรดิถูกปิดล้อมทั้งตะวันตกโดยชาวนอร์แมน และทางตะวันออกโดยเซลจุกเติร์กทำให้จักรพรรดิ อเล็กเซียสที่ 1 (ค.ศ. 1081-1811) ต้องไปขอความช่วยเหลือจากพวกเวนิส โดยที่พระองค์ต้องยอมตกลงตามข้อเรียกร้องของเวนิส โดยการให้สิทธิการค้าในกรุงคอนสแตนติโนเปิลและที่อื่น ๆ ในไบแซนไทน์ ซึ่งข้อตกลงนี้เองทำให้ชาวเวนิสกลายมาเป็นพ่อค้าสำคัญในด้านตะวันออกของทะเลเมดิเตอร์เรเนียนในเวลาต่อมา

สงครามครูเสด การรุกรานของชนทั้งสองต่อไบแซนไทน์ก็ยังไม่สิ้นสุดลงจนกระทั่งจักรพรรดิอเล็กเซียสที่ 1 จำต้องขอความชั่วเหลือไปยังสมเด็จพระสันตะปาปา โดยยกขออ้างให้ช่วยเหลือเมืองเยรูซาเล็ม ดินแดนศักดิ์สิทธิ์ที่ถูกเติร์กยึดครองไปตั้งแต่ ค.ศ. 1077 และกองทัพครูเสดครั้งที่ 1 ก็ถูกส่งเข้ามา

ด้วยชัยชนะของกองทัพครูเสดดินแดนบางส่วนก็ได้ส่งคืนให้กับจักรพรรดิไบแซนไทน์ แต่บางส่วนแม่ทัพชาวมอร์แมนกลับไม่ยอมยกคืนให้ทั้งที่ค่าใช้จ่ายต่าง ๆ นั้นจักรพรรดิไบแซนไทน์เป็นผู้ที่เสียให้เกือบทั้งหมด ผ่านพ้นสงครามครูเสดครั้งที่ 1 พวกเติร์กก็ยังรุกรานอยู่เช่นเดิม จักรพรรดิองค์ต่อมาเห็นว่าชาวตะวันตกมีบทบาทจึงได้ดำเนินนโยบายเป็นมิตรกับชาวตะวันตกเอาไว้ ต่อมาเกิดสงครามครูเสดครั้งที่ 2 กองทัพครูเสดต้องใช้ไบแซนไทน์เป็นทางผ่านทำให้ไบแซนไทน์ถูกกองทัพครูเสดบางกลุ่มเข้าปล้น

จักรวรรดิล่มสลาย[แก้]

ไบแซนไทน์ยังต้องทำสงครามกับเติร์กมาโดยตลอดจนกระทั่งถึงคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 15 โดยชาวเติร์กรุกเข้ามาในจักรวรรดิ โดยเริ่มจาก ค.ศ. 1377 เติร์กประกาศตั้งเมืองหลวงของออตโตมันที่อเดรียนเนเปิล ค.ศ. 1385 ก็ยึดเมืองโซเฟีย ค.ศ. 1386 ได้เมืองนีส เมืองเทสสาโลนิกา

พฤษภาคม ค.ศ. 1453 จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ก็ต้องพ่ายแพ้แก่จักรวรรดิออตโตมันของชาวเติร์ก และถูกรวมเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของจักรวรรดิออตโตมันในที่สุด จักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันออกหรือจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ ก็ล่มสลายลง จักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์นั้นรักษาวัฒธรรมของโรมันและวัฒธรรมกรีก เป็นระยะเวลา 1123 ปี ตั้งแต่ปี ค.ศ. 330-1453

การล่มสลายของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ เกิดขึ้นหลังจากที่กรุงคอนสแตนติโนเปิลถูกยึดโดยชาวออตโตมันเติร์ก ในปี ค.ศ. 1453 หลังจากกรุงคอนสแตนติโนเปิลแตกก็ได้ถูกเปลี่ยนชื่อใหม่เป็นอิสตันบูลมาจนถึงปัจจุบัน และในทางประวัติศาสตร์ยังได้ถือว่าการสิ้นสุดของจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์เป็นที่สิ้นสุดของยุคกลางในยุโรป

Government and bureaucracy[แก้]

In the Byzantine state, the emperor was the sole and absolute ruler, and his power was regarded as having divine origin.[72] From Justinian I on, the emperor was considered nomos empsychos, the "living law", both lawgiver and administrator.[73] The Senate had ceased to have real political and legislative authority but remained as an honorary council with titular members. By the end of the 8th century, a civil administration focused on the court was formed as part of a large-scale consolidation of power in the capital (the rise to pre-eminence of the position of sakellarios is related to this change).[74] The most important administrative reform, which probably started in the mid-7th century, was the creation of themes, where civil and military administration was exercised by one person, the strategos.[75]

Despite the occasionally derogatory use of the terms "Byzantine" and "Byzantinism", the Byzantine bureaucracy had a distinct ability for adapting to the Empire's changing situations. The elaborate system of titulature and precedence gave the court prestige and influence. Officials were arranged in strict order around the emperor and depended upon the imperial will for their ranks. There were also actual administrative jobs, but authority could be vested in individuals rather than offices.[76]

In the 8th and 9th centuries, civil service constituted the clearest path to aristocratic status, but, starting in the 9th century, the civil aristocracy was rivalled by an aristocracy of nobility. According to some studies of the Byzantine government, 11th-century politics were dominated by competition between the civil and the military aristocracy. During this period, Alexios I undertook important administrative reforms, including the creation of new courtly dignities and offices.[77]

Diplomacy[แก้]

After the fall of Rome, the key challenge to the Empire was to maintain a set of relations between itself and its neighbours. When these nations set about forging formal political institutions, they often modelled themselves on Constantinople. Byzantine diplomacy soon managed to draw its neighbours into a network of international and inter-state relations.[78] This network revolved around treaty-making, and included the welcoming of the new ruler into the family of kings, and the assimilation of Byzantine social attitudes, values and institutions.[79] Whereas classical writers are fond of making ethical and legal distinctions between peace and war, Byzantines regarded diplomacy as a form of war by other means. For example, a Bulgarian threat could be countered by providing money to the Kievan Rus'.[80]

Diplomacy in the era was understood to have an intelligence-gathering function on top of its pure political function. The Bureau of Barbarians in Constantinople handled matters of protocol and record-keeping for any issues related to the "barbarians", and thus had, perhaps, a basic intelligence function itself.[81] John B. Bury believed that the office exercised supervision over all foreigners visiting Constantinople, and that they were under the supervision of the Logothetes tou dromou.[82] While on the surface a protocol office – its main duty was to ensure foreign envoys were properly cared for and received sufficient state funds for their maintenance, and it kept all the official translators – it probably had a security function as well.[83]

Byzantines availed themselves of several diplomatic practices. For example, embassies to the capital often stayed on for years. A member of other royal houses would routinely be requested to stay on in Constantinople, not only as a potential hostage but also as a useful pawn in case political conditions where he came from changed. Another key practise was to overwhelm visitors by sumptuous displays.[78] According to Dimitri Obolensky, the preservation of the ancient civilisation in Europe was due to the skill and resourcefulness of Byzantine diplomacy, which remains one of Byzantium's lasting contributions to the history of Europe.[84]

Law[แก้]

In 438, the Codex Theodosianus, named after Theodosius II, codified Byzantine law. It went into force not just in the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire, but also in the Western Roman Empire. It not only summarised the laws but also gave direction on interpretation.

Under the reign of Justinian I it was Tribonian, a notable jurist, who supervised the revision of the legal code known today as the Corpus Juris Civilis. Justinian's reforms had a clear effect on the evolution of jurisprudence, with his Corpus Juris Civilis becoming the basis for revived Roman law in the Western world, while Leo III's Ecloga influenced the formation of legal institutions in the Slavic world.[85]

In the 10th century, Leo VI the Wise achieved the complete codification of the whole of Byzantine law in Greek with the Basilika, which became the foundation of all subsequent Byzantine law with an influence extending through to modern Balkan legal codes.[86]

Science and medicine[แก้]

The writings of Classical antiquity were cultivated and extended in Byzantium. Therefore, Byzantine science was in every period closely connected with ancient philosophy, and metaphysics.[87] In the field of engineering Isidore of Miletus, the Greek mathematician and architect of the Hagia Sophia, produced the first compilation of Archimedes' works c. 530, and it is through this manuscript tradition, kept alive by the school of mathematics and engineering founded c. 850 during the "Byzantine Renaissance" by Leo the Mathematician, that such works are known today (see Archimedes Palimpsest).[88]

Pendentive architecture, a specific spherical form in the upper corners to support a dome, is a Byzantine invention. Although the first experimentation was made in the 200s, it was in the 6th century in the Byzantine Empire that its potential was fully achieved.[89]

A mechanical sundial device consisting of complex gears made by the Byzantines has been excavated which indicates that the Antikythera mechanism, a sort of analogue device used in astronomy and invented around the late second century BC, continued to be (re)active in the Byzantine period.[90][91][92] J. R. Partington writes that

Constantinople was full of inventors and craftsmen. The "philosopher" Leo of Thessalonika made for the Emperor Theophilos (829–842) a golden tree, the branches of which carried artificial birds which flapped their wings and sang a model lion which moved and roared, and a bejewelled clockwork lady who walked. These mechanical toys continued the tradition represented in the treatise of Heron of Alexandria (c. A.D. 125), which was well-known to the Byzantines.[93]

Such mechanical devices reached a high level of sophistication and were made to impress visitors.[94]

Leo the Mathematician has also been credited with the system of beacons, a sort of optical telegraph, stretching across Anatolia from Cilicia to Constantinople, which gave warning of enemy raids, and which was used as diplomatic communication as well.

The Byzantines knew and used the concept of hydraulics: in the 900s the diplomat Liutprand of Cremona, when visiting the Byzantine emperor, explained that he saw the emperor sitting on a hydraulic throne and that it was "made in such a cunning manner that at one moment it was down on the ground, while at another it rose higher and was seen to be up in the air".[95]

John Philoponus, an Alexandrian philologist, Aristotelian commentator and Christian theologian, author of a considerable number of philosophical treatises and theological works, was the first who questioned Aristotle's teaching of physics, despite its flaws. Unlike Aristotle, who based his physics on verbal argument, Philoponus relied on observation. In his Commentaries on Aristotle, Philoponus wrote:

But this is completely erroneous, and our view may be corroborated by actual observation more effectively than by any sort of verbal argument. For if you let fall from the same height two weights of which one is many times as heavy as the other, you will see that the ratio of the times required for the motion does not depend on the ratio of the weights, but that the difference in time is a very small one. And so, if the difference in the weights is not considerable, that is, of one is, let us say, double the other, there will be no difference, or else an imperceptible difference, in time, though the difference in weight is by no means negligible, with one body weighing twice as much as the other.[96]

John Philoponus' criticism of Aristotelian principles of physics was an inspiration for Galileo Galilei's refutation of Aristotelian physics during the Scientific Revolution many centuries later, as Galileo cited Philoponus substantially in his works.[97][98]

The ship mill is a Byzantine invention, designed to mill grains using hydraulic power. The technology eventually spread to the rest of Europe and was in use until c. 1800.[99][100]

The Byzantines pioneered the concept of the hospital as an institution offering medical care and the possibility of a cure for the patients, as a reflection of the ideals of Christian charity, rather than merely a place to die.[101]

Although the concept of uroscopy was known to Galen, he did not see the importance of using it to diagnose disease. It was Byzantine physicians, such as Theophilus Protospatharius, who realised the diagnostic potential of uroscopy in a time when no microscope or stethoscope existed. That practice eventually spread to the rest of Europe.[102]

In medicine, the works of Byzantine doctors, such as the Vienna Dioscorides (6th century), and works of Paul of Aegina (7th century) and Nicholas Myrepsos (late 13th century), continued to be used as the authoritative texts by Europeans through the Renaissance. The latter one invented the Aurea Alexandrina which was a kind of opiate or antidote.

The first known example of separating conjoined twins happened in the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century when a pair of conjoined twins from Armenia came to Constantinople. Many years later one of them died, so the surgeons in Constantinople decided to remove the body of the dead one. The result was partly successful, as the surviving twin lived three days before dying, a result so impressive that it was mentioned a century and a half later by historians. The next case of separating conjoined twins did not occur until 1689 in Germany.[103][104]

Greek fire, an incendiary weapon which could even burn on water, is also attributed to the Byzantines. It played a crucial role in the Empire's victory over the Umayyad Caliphate during the siege of Constantinople (717–718).[105] The discovery is attributed to Callinicus of Heliopolis from Syria who fled during the Arab conquest of Syria. However, it has also been argued that no single person invented Greek fire, but rather, that it was "invented by the chemists in Constantinople who had inherited the discoveries of the Alexandrian chemical school...".[93]

The first example of a grenade also appeared in the Byzantine Empire, consisting of ceramic jars holding glass and nails, and filled with the explosive component of Greek Fire. It was used on battlefields.[106][107][108]

The first examples of hand-held flamethrower also occurred in the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century, where infantry units were equipped with hand pumps and swivel tubes used to project the flame.[109]

The counterweight trebuchet was invented in the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) under the Komnenian restoration when the Byzantines used this new-developed siege weaponry to devastate citadels and fortifications. This siege artillery marked the apogee of siege weaponry before the use of the cannon. From the Byzantines, the armies of Europe and Asia eventually learned and adopted this siege weaponry.[110]

In the final century of the Empire, astronomy and other mathematical sciences were taught in Trebizond; medicine attracted the interest of almost all scholars.[111]

The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 fuelled the era later commonly known as the "Italian Renaissance". During this period, refugee Byzantine scholars were principally responsible for carrying, in person and writing, ancient Greek grammatical, literary studies, mathematical, and astronomical knowledge to early Renaissance Italy.[112] They also brought with them classical learning and texts on botany, medicine and zoology, as well as the works of Dioscorides and John Philoponus' criticism of Aristotelian physics.[98]

Culture[แก้]

Religion[แก้]

The Byzantine Empire was a theocracy, said to be ruled by God working through the Emperor. Jennifer Fretland VanVoorst argues, "The Byzantine Empire became a theocracy in the sense that Christian values and ideals were the foundation of the empire's political ideals and heavily entwined with its political goals."[113] Steven Runciman says in his book on The Byzantine Theocracy (2004):

The constitution of the Byzantine Empire was based on the conviction that it was the earthly copy of the Kingdom of Heaven. Just as God ruled in Heaven, so the Emperor, made in his image, should rule on earth and carry out his commandments ... It saw itself as a universal empire. Ideally, it should embrace all the peoples of the Earth who, ideally, should all be members of the one true Christian Church, its own Orthodox Church. Just as man was made in God's image, so man's kingdom on Earth was made in the image of the Kingdom of Heaven.[114]

The survival of the Empire in the East assured an active role of the Emperor in the affairs of the Church. The Byzantine state inherited from pagan times the administrative, and financial routine of administering religious affairs, and this routine was applied to the Christian Church. Following the pattern set by Eusebius of Caesarea, the Byzantines viewed the Emperor as a representative or messenger of Christ, responsible particularly for the propagation of Christianity among pagans, and for the "externals" of the religion, such as administration and finances. As Cyril Mango points out, the Byzantine political thinking can be summarised in the motto "One God, one empire, one religion".[115]

The imperial role in the affairs of the Church never developed into a fixed, legally defined system.[116] Additionally, due to the decline of Rome and internal dissension in the other Eastern Patriarchates, the Church of Constantinople became, between the 6th and 11th centuries, the richest and most influential centre of Christendom.[117] Even when the Empire was reduced to only a shadow of its former self, the Church continued to exercise significant influence both inside and outside of the imperial frontiers. As George Ostrogorsky points out:

The Patriarchate of Constantinople remained the centre of the Orthodox world, with subordinate metropolitan sees and archbishoprics in the territory of Asia Minor and the Balkans, now lost to Byzantium, as well as in Caucasus, Russia and Lithuania. The Church remained the most stable element in the Byzantine Empire.[118]

Byzantine monasticism especially came to be an "ever-present feature" of the empire, with monasteries becoming "powerful landowners and a voice to be listened to in imperial politics".[119]

The official state Christian doctrine was determined by the first seven ecumenical councils, and it was then the emperor's duty to impose it on his subjects. An imperial decree of 388, which was later incorporated into the Codex Justinianeus, orders the population of the Empire "to assume the name of Catholic Christians", and regards all those who will not abide by the law as "mad and foolish persons"; as followers of "heretical dogmas".[120]

Despite imperial decrees and the stringent stance of the state church itself, which came to be known as the Eastern Orthodox Church or Eastern Christianity, the latter never represented all Christians in Byzantium. Mango believes that, in the early stages of the Empire, the "mad and foolish persons", those labelled "heretics" by the state church, were the majority of the population.[121] Besides the pagans, who existed until the end of the 6th century, and the Jews, there were many followers – sometimes even emperors – of various Christian doctrines, such as Nestorianism, Monophysitism, Arianism, and Paulicianism, whose teachings were in some opposition to the main theological doctrine, as determined by the Ecumenical Councils.[122]

Another division among Christians occurred, when Leo III ordered the destruction of icons throughout the Empire. This led to a significant religious crisis, which ended in the mid-9th century with the restoration of icons. During the same period, a new wave of pagans emerged in the Balkans, originating mainly from Slavic people. These were gradually Christianised, and by Byzantium's late stages, Eastern Orthodoxy represented most Christians and, in general, most people in what remained of the Empire.[123]

Jews were a significant minority in the Byzantine state throughout its history, and, according to Roman law, they constituted a legally recognised religious group. In the early Byzantine period, they were generally tolerated, but then periods of tensions and persecutions ensued. In any case, after the Arab conquests, the majority of Jews found themselves outside the Empire; those left inside the Byzantine borders apparently lived in relative peace from the 10th century onwards.[124]

The arts[แก้]

Art[แก้]

Surviving Byzantine art is mostly religious and with exceptions at certain periods is highly conventionalised, following traditional models that translate carefully controlled church theology into artistic terms. Painting in fresco, illuminated manuscripts and on wood panel and, especially in earlier periods, mosaic were the main media, and figurative sculpture very rare except for small carved ivories. Manuscript painting preserved to the end some of the classical realist tradition that was missing in larger works.[125] Byzantine art was highly prestigious and sought-after in Western Europe, where it maintained a continuous influence on medieval art until near the end of the period. This was especially so in Italy, where Byzantine styles persisted in modified form through the 12th century, and became formative influences on Italian Renaissance art. But few incoming influences affected the Byzantine style. With the expansion of the Eastern Orthodox church, Byzantine forms and styles spread throughout the Orthodox world and beyond.[126] Influences from Byzantine architecture, particularly in religious buildings, can be found in diverse regions from Egypt and Arabia to Russia and Romania.

Literature[แก้]

In Byzantine literature, three different cultural elements are recognised: the Greek, the Christian, and the Oriental. Byzantine literature is often classified in five groups: historians and annalists, encyclopaedists (Patriarch Photios, Michael Psellus, and Michael Choniates are regarded as the greatest encyclopaedists of Byzantium) and essayists, and writers of secular poetry. The only genuine heroic epic of the Byzantines is the Digenis Acritas. The remaining two groups include the new literary species: ecclesiastical and theological literature, and popular poetry.[127]

Of the approximately two to three thousand volumes of Byzantine literature that survive, only 330 consist of secular poetry, history, science and pseudo-science.[127] While the most flourishing period of the secular literature of Byzantium runs from the 9th to the 12th century, its religious literature (sermons, liturgical books and poetry, theology, devotional treatises, etc.) developed much earlier with Romanos the Melodist being its most prominent representative.[128]

Music[แก้]

The ecclesiastical forms of Byzantine music, composed to Greek texts as ceremonial, festival, or church music,[130] are, today, the most well-known forms. Ecclesiastical chants were a fundamental part of this genre. Greek and foreign historians agree that the ecclesiastical tones and in general the whole system of Byzantine music is closely related to the ancient Greek system.[131] It remains the oldest genre of extant music, of which the manner of performance and (with increasing accuracy from the 5th century onwards) the names of the composers, and sometimes the particulars of each musical work's circumstances, are known.

The 9th-century Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh (d. 911), in his lexicographical discussion of instruments, cited the lyra (lūrā) as the typical instrument of the Byzantines along with the urghun (organ), shilyani (probably a type of harp or lyre) and the salandj (probably a bagpipe).[132] The first of these, the early bowed stringed instrument known as the Byzantine lyra, came to be called the lira da braccio,[133] in Venice, where it is considered by many to have been the predecessor of the contemporary violin, which later flourished there.[134] The bowed "lyra" is still played in former Byzantine regions, where it is known as the Politiki lyra (แปลว่า lyra of the City, i.e. Constantinople) in Greece, the Calabrian lira in Southern Italy, and the Lijerica in Dalmatia. The second instrument, the organ, originated in the Hellenistic world (see Hydraulis) and was used in the Hippodrome during races.[135][136] A pipe organ with "great leaden pipes" was sent by the emperor Constantine V to Pepin the Short, King of the Franks in 757. Pepin's son Charlemagne requested a similar organ for his chapel in Aachen in 812, beginning its establishment in Western church music.[136] The aulos was a double reeded woodwind like the modern oboe or Armenian duduk. Other forms include the plagiaulos (πλαγίαυλος, from πλάγιος "sideways"), which resembled the flute,[137] and the askaulos (ἀσκός askos – wine-skin), a bagpipe.[138] Bagpipes, also known as Dankiyo (from ancient Greek: angion (Τὸ ἀγγεῖον) "the container"), had been played even in Roman times and continued to be played throughout the empire's former realms through to the present. (See Balkan Gaida, Greek Tsampouna, Pontic Tulum, Cretan Askomandoura, Armenian Parkapzuk, and Romanian Cimpoi.) The modern descendant of the aulos is the Greek Zourna. Other instruments used in Byzantine Music were Kanonaki, Oud, Laouto, Santouri, Tambouras, Seistron (defi tambourine), Toubeleki and Daouli. Some claim that Lavta may have been invented by the Byzantines before the arrival of the Turks.[ต้องการอ้างอิง]

Cuisine[แก้]

Byzantine culture was initially the same as Late Greco-Roman, but over the following millennium of the empire's existence it slowly changed into something more similar to modern Balkan and Anatolian culture. The cuisine still relied heavily on the Greco-Roman fish-sauce condiment garos, but it also contained foods still familiar today, such as the cured meat pastirma (known as "paston" in Byzantine Greek),[139][140][141] baklava (known as koptoplakous κοπτοπλακοῦς),[142] tiropita (known as plakountas tetyromenous or tyritas plakountas),[143] and the famed medieval sweet wines (Commandaria and the eponymous Rumney wine). Retsina, wine flavoured with pine resin, was also drunk, as it still is in Greece today, producing similar reactions from unfamiliar visitors; "To add to our calamity the Greek wine, on account of being mixed with pitch, resin, and plaster was to us undrinkable," complained Liutprand of Cremona, who was the ambassador sent to Constantinople in 968 by the German Holy Roman Emperor Otto I.[144] The garos fish sauce condiment was also not much appreciated by the unaccustomed; Liutprand of Cremona described being served food covered in an "exceedingly bad fish liquor."[144] The Byzantines also used a soy sauce-like condiment, murri, a fermented barley sauce, which, like soy sauce, provided umami flavouring to their dishes.[145][146]

Flags and insignia[แก้]

For most of its history, the Byzantine Empire did not know or use heraldry in the West European sense. Various emblems (กรีก: σημεία, sēmeia; sing. σημείον, sēmeion) were used in official occasions and for military purposes, such as banners or shields displaying various motifs such as the cross or the labarum. The use of the cross and images of Christ, the Virgin Mary and various saints is also attested on seals of officials, but these were personal rather than family emblems.[147]

Language[แก้]

Right: The Joshua Roll, a 10th-century illuminated Greek manuscript possibly made in Constantinople (Vatican Library, Rome)

Apart from the Imperial court, administration and military, the primary language used in the eastern Roman provinces even before the decline of the Western Empire was Greek, having been spoken in the region for centuries before Latin.[149] Following Rome's conquest of the east its 'Pax Romana', inclusionist political practices and development of public infrastructure, facilitated the further spreading and entrenchment of the Greek language in the east. Indeed, early on in the life of the Roman Empire, Greek had become the common language of the Church, the language of scholarship and the arts, and to a large degree the lingua franca for trade between provinces and with other nations.[150] Greek for a time became diglossic with the spoken language, known as Koine (eventually evolving into Demotic Greek), used alongside an older written form (Attic Greek) until Koine won out as the spoken and written standard.[151]

The emperor Diocletian (ค. 284 – 305) sought to renew the authority of Latin, making it the official language of the Roman administration also in the East, and the Greek expression ἡ κρατοῦσα διάλεκτος (hē kratousa dialektos) attests to the status of Latin as "the language of power."[152] In the early 5th century, Greek gained equal status with Latin as the official language in the East and emperors gradually began to legislate in Greek rather than Latin starting with the reign of Leo I the Thracian in the 460s.[27] The last Eastern emperor to stress the importance of Latin was Justinian I (ค. 527 – 565), whose Corpus Juris Civilis was written almost entirely in Latin. He may also have been the last native Latin-speaking emperor.[27]

The use of Latin as the language of administration persisted until the adoption of Greek as the sole official language by Heraclius in the 7th century. Scholarly Latin rapidly fell into disuse among the educated classes although the language continued to be at least a ceremonial part of the Empire's culture for some time.[153] Additionally, Latin remained a minority language in the Empire, mainly on the Italian peninsula, along the Dalmatian coast and in the Balkans (specially in mountainous areas away from the coast), eventually developing into various Romance languages like Dalmatian or Romanian.[154]

Many other languages existed in the multi-ethnic Empire, and some of these were given limited official status in their provinces at various times.[155] Notably, by the beginning of the Middle Ages, Syriac had become more widely used by the educated classes in the far eastern provinces.[156] Similarly Coptic, Armenian, and Georgian became significant among the educated in their provinces.[157] Later foreign contacts made Old Church Slavic, Middle Persian, and Arabic important in the Empire and its sphere of influence.[158] There was a revival of Latin studies in the 10th century for the same reason and by the 11th century knowledge of Latin was no longer unusual at Constantinople.[159] There was widespread use of the Armenian and various Slavic languages, which became more pronounced in the border regions of the empire.[155]

Aside from these languages, since Constantinople was a prime trading center in the Mediterranean region and beyond, virtually every known language of the Middle Ages was spoken in the Empire at some time, even Chinese.[160] As the Empire entered its final decline, the Empire's citizens became more culturally homogeneous and the Greek language became integral to their identity and religion.[161]

Recreation[แก้]

Byzantines were avid players of tavli (Byzantine Greek: τάβλη), a game known in English as backgammon, which is still popular in former Byzantine realms, and still known by the name tavli in Greece.[162] Byzantine nobles were devoted to horsemanship, particularly tzykanion, now known as polo. The game came from Sassanid Persia in the early period and a Tzykanisterion (stadium for playing the game) was built by Theodosius II (ค. 408 – 450) inside the Great Palace of Constantinople. Emperor Basil I (ค. 867 – 886) excelled at it; Emperor Alexander (ค. 912 – 913) died from exhaustion while playing, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (ค. 1081 – 1118) was injured while playing with Tatikios, and John I of Trebizond (ค. 1235 – 1238) died from a fatal injury during a game.[163][164] Aside from Constantinople and Trebizond, other Byzantine cities also featured tzykanisteria, most notably Sparta, Ephesus, and Athens, an indication of a thriving urban aristocracy.[165] The game was introduced to the West by crusaders, who developed a taste for it particularly during the pro-Western reign of emperor Manuel I Komnenos.

Women in the Byzantine Empire[แก้]

The position of women in the Byzantine Empire essentially represents the position of women in ancient Rome transformed by the introduction of Christianity, with certain rights and customs being lost and replaced, while others were allowed to remain.

There were individual Byzantine women famed for their educational accomplishments. However, the general view of women's education was that it was sufficient for a girl to learn domestic duties and to study the lives of the Christian saints and memorize psalms,[166] and to learn to read so that she could study Bible scriptures – although literacy in women was sometimes discouraged because it was believed it could encourage vice.[167]

The Roman right to actual divorce was gradually erased after the introduction of Christianity and replaced with legal separation and annulation. In the Byzantine Empire marriage was regarded as the ideal state for a woman, and only convent life was seen as a legitimate alternative. Within marriage, sexual activity was regarded only as a means of reproduction. Women had the right to appear before court, but her testimony was not regarded as equal to that of a man, and could be contradicted based on her sex if put against that of a man.[166]

From the 6th century there was a growing ideal of gender segregation, which dictated that women should wear veils[168] and only be seen in public when attending church,[169] and while the ideal was never fully enforced, it influenced society. The laws of emperor Justinian I made it legal for a man to divorce his wife for attending public premises such as theatres or public baths without his permission,[170] and emperor Leo VI banned women from witnessing business contracts with the argument that it caused them to come in contact with men.[166] In Constantinople upper-class women were increasingly expected to keep to a special women's section (gynaikonitis),[169] and by the 8th century it was described as unacceptable for unmarried daughters to meet unrelated men.[166] While imperial women and their ladies appeared in public alongside men, women and men at the imperial court attended royal banquets separately until the rise of the Comnenus dynasty in the 12th century.[169]

Eastern Roman and later Byzantine women retained the Roman woman's right to inherit, own and manage their property and signs contracts,[169] rights which were far superior to the rights of married women in Medieval Catholic Western Europe, as these rights included not only unmarried women and widows but married women as well.[170] Women's legal right to handle their own money made it possible for rich women to engage in business, however women who actively had to find a profession to support themselves normally worked as domestics or in domestic fields such as the food- or textile industry.[170] Women could work as medical physicians and attendants of women patients and visitors at hospitals and public baths with government support.[167]

After the introduction of Christianity, women could no longer become priestesses, but it became common for women to found and manage nunneries, which functioned as schools for girls as well as asylums, poor houses, hospitals, prisons and retirement homes for women, and many Byzantine women practised social work as lay sisters and deaconesses.[169]

Economy[แก้]

The Byzantine economy was among the most advanced in Europe and the Mediterranean for many centuries. Europe, in particular, could not match Byzantine economic strength until late in the Middle Ages. Constantinople operated as a prime hub in a trading network that at various times extended across nearly all of Eurasia and North Africa, in particular as the primary western terminus of the famous Silk Road. Until the first half of the 6th century and in sharp contrast with the decaying West, the Byzantine economy was flourishing and resilient.[171]

The Plague of Justinian and the Arab conquests represented a substantial reversal of fortunes contributing to a period of stagnation and decline. Isaurian reforms and Constantine V's repopulation, public works and tax measures marked the beginning of a revival that continued until 1204, despite territorial contraction.[172] From the 10th century until the end of the 12th, the Byzantine Empire projected an image of luxury and travellers were impressed by the wealth accumulated in the capital.[173]

The Fourth Crusade resulted in the disruption of Byzantine manufacturing and the commercial dominance of the Western Europeans in the eastern Mediterranean, events that amounted to an economic catastrophe for the Empire.[173] The Palaiologoi tried to revive the economy, but the late Byzantine state did not gain full control of either the foreign or domestic economic forces. Gradually, Constantinople also lost its influence on the modalities of trade and the price mechanisms, and its control over the outflow of precious metals and, according to some scholars, even over the minting of coins.[174]

One of the economic foundations of Byzantium was trade, fostered by the maritime character of the Empire. Textiles must have been by far the most important item of export; silks were certainly imported into Egypt and appeared also in Bulgaria, and the West.[175] The state strictly controlled both the internal and the international trade, and retained the monopoly of issuing coinage, maintaining a durable and flexible monetary system adaptable to trade needs.[176]

The government attempted to exercise formal control over interest rates and set the parameters for the activity of the guilds and corporations, in which it had a special interest. The emperor and his officials intervened at times of crisis to ensure the provisioning of the capital, and to keep down the price of cereals. Finally, the government often collected part of the surplus through taxation, and put it back into circulation, through redistribution in the form of salaries to state officials, or in the form of investment in public works.[176]

Legacy[แก้]

Byzantium has been often identified with absolutism, orthodox spirituality, orientalism and exoticism, while the terms "Byzantine" and "Byzantinism" have been used as bywords for decadence, complex bureaucracy, and repression. Both Eastern and Western European authors have often perceived Byzantium as a body of religious, political, and philosophical ideas contrary to those of the West. Even in 19th-century Greece, the focus was mainly on the classical past, while Byzantine tradition had been associated with negative connotations.[177]

This traditional approach towards Byzantium has been partially or wholly disputed and revised by modern studies, which focus on the positive aspects of Byzantine culture and legacy. Averil Cameron regards as undeniable the Byzantine contribution to the formation of medieval Europe, and both Cameron and Obolensky recognise the major role of Byzantium in shaping Orthodoxy, which in turn occupies a central position in the history, societies and culture of Greece, Romania, Bulgaria, Russia, Georgia, Serbia and other countries.[178] The Byzantines also preserved and copied classical manuscripts, and they are thus regarded as transmitters of classical knowledge, as important contributors to modern European civilisation, and as precursors of both Renaissance humanism and Slavic-Orthodox culture.[179]

As the only stable long-term state in Europe during the Middle Ages, Byzantium isolated Western Europe from newly emerging forces to the East. Constantly under attack, it distanced Western Europe from Persians, Arabs, Seljuk Turks, and for a time, the Ottomans. From a different perspective, since the 7th century, the evolution and constant reshaping of the Byzantine state were directly related to the respective progress of Islam.[179]

Following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II took the title "Kaysar-i Rûm" (the Ottoman Turkish equivalent of Caesar of Rome), since he was determined to make the Ottoman Empire the heir of the Eastern Roman Empire.[180]

หมายเหตุ[แก้]

- ↑ หรือที่เรียกอีกชื่อหนึ่งว่า จักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันออก ในขณะที่ยังมีจักรวรรดิโรมันตะวันตกอยู่ และจักรวรรดิไบแซนทิอุม (กรีก: Βασιλεία των Ρωμαίων)

- ↑ "โรมาเนีย" เป็นชื่อที่นิยมใช้กันโดยทั่วไปในจักรวรรดิไบแซนไทน์ ซึ่งหมายถึ่ง "ดินแดนแห่งชาวโรมัน"[4] ภายหลัง ค.ศ. 1081 คำนี้ก็ได้ปรากฏบนเอกสารทางราชการของไบแซนไทน์เป็นบางครั้งอีกด้วย ใน ค.ศ. 1204 ผู้นำในสงครามครูเสดครั้งที่ 4 ได้ตั้งชื่อ โรมาเนีย ให้กับจักรวรรดิละตินที่เพิ่งก่อตั้งขึ้นมาใหม่[5] แต่คำนี้ไม่ได้หมายถึงประเทศโรมาเนียในปัจจุบัน

อ้างอิง[แก้]

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/topic/Byzantine-Greek-language

- ↑ Fox, What, If Anything, Is a Byzantine?; Rosser 2011, p. 1

- ↑ Rosser 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ Fossier & Sondheimer 1997, p. 104.

- ↑ Wolff 1948, pp. 5–7, 33–34.

- ↑ Cinnamus 1976, p. 240.

- ↑ Browning 1992, "Introduction", p. xiii: "The Byzantines did not call themselves Byzantines, but Romaioi–Romans. They were well aware of their role as heirs of the Roman Empire, which for many centuries had united under a single government the whole Mediterranean world and much that was outside it."

- ↑ Nicol, Donald M. (30 December 1967). "The Byzantine View of Western Europe". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies (ภาษาอังกฤษ). 8 (4): 318. ISSN 2159-3159.

- ↑ Ahrweiler & Laiou 1998, p. 3; Mango 2002, p. 13.

- ↑ Gabriel 2002, p. 277.

- ↑ Ahrweiler & Laiou 1998, p. vii; Davies 1996, p. 245; Gross 1999, p. 45; Lapidge, Blair & Keynes 1998, p. 79; Millar 2006, pp. 2, 15; Moravcsik 1970, pp. 11–12; Ostrogorsky 1969, pp. 28, 146; Browning 1983, p. 113.

- ↑ Klein 2004, p. 290 (Note #39); Annales Fuldenses, 389: "Mense lanuario c. epiphaniam Basilii, Graecorum imperatoris, legati cum muneribus et epistolis ad Hludowicum regem Radasbonam venerunt ...".

- ↑ Fouracre & Gerberding 1996, p. 345: "The Frankish court no longer regarded the Byzantine Empire as holding valid claims of universality; instead it was now termed the 'Empire of the Greeks'."

- ↑ Tarasov & Milner-Gulland 2004, p. 121; El-Cheikh 2004, p. 22

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ostrogorsky 1959, p. 21; Wells 1922, Chapter 33.

- ↑ Bury 1923, p. 1; Kuhoff 2002, pp. 177–178.

- ↑ Bury 1923, p. 1; Esler 2004, p. 1081; Gibbon 1906, Volume III, Part IV, Chapter 18, p. 168; Teall 1967, pp. 13, 19–23, 25, 28–30, 35–36

- ↑ Bury 1923, p. 63; Drake 1995, p. 5; Grant 1975, pp. 4, 12.

- ↑ Bowersock 1997, p. 79.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 1.

- ↑ Friell & Williams 2005, p. 105.

- ↑ Perrottet 2004, p. 190.

- ↑ Cameron 2009, pp. 54, 111, 153.

- ↑ Alemany 2000, p. 207; Bayless 1976, pp. 176–177; Treadgold 1997, pp. 184, 193.

- ↑ Chapman 1971, p. 210

- ↑ Meier 2003, p. 290.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 The Inheritance of Rome, Chris Wickham, Penguin Books Ltd. 2009, ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0. p. 90.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, p. 17

- ↑ Evans 2005, p. 104

- ↑ Gregory 2010, p. 150.

- ↑ Merryman & Perez-Perdomo 2007, p. 7

- ↑ Gregory 2010, p. 137; Meier 2003, pp. 297–300.

- ↑ Gregory 2010, p. 145.

- ↑ Evans 2005, p. xxv.

- ↑ Bury 1923, pp. 180–216; Evans 2005, pp. xxvi, 76.

- ↑ Sotinel 2005, p. 278; Treadgold 1997, p. 187.

- ↑ Bury 1923, pp. 236–258; Evans 2005, p. xxvi.

- ↑ Bury 1923, pp. 259–281; Evans 2005, p. 93.

- ↑ Bury 1923, pp. 286–288; Evans 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ Greatrex 2005, p. 489; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 113

- ↑ Bury 1920, "Preface", pp. v–vi

- ↑ Evans 2005, pp. 11, 56–62; Sarantis 2009, passim.

- ↑ Evans 2005, p. 65

- ↑ Evans 2005, p. 68

- ↑ Cameron 2009, pp. 113, 128.

- ↑ Bray 2004, pp. 19–47; Haldon 1990, pp. 110–111; Treadgold 1997, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Kazhdan 1991.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Louth 2005, pp. 113–115; Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou 1970, passim; Treadgold 1997, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 33

- ↑ Foss 1975, p. 722.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, p. 41; Speck 1984, p. 178.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Grabar 1984, p. 37; Cameron 1979, p. 23.

- ↑ Cameron 1979, pp. 5–6, 20–22.

- ↑ Norwich 1998, p. 93

- ↑ Haldon 1990, p. 46; Baynes 1912, passim; Speck 1984, p. 178.

- ↑ Foss 1975, pp. 746–747.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, p. 50.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, pp. 102–114; Laiou & Morisson 2007, p. 47.

- ↑ Laiou & Morisson 2007, pp. 38–42, 47; Wickham 2009, p. 260.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, pp. 208–215; Kaegi 2003, pp. 236, 283.

- ↑ Heather 2005, p. 431.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, pp. 43–45, 66, 114–115

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Haldon 1990, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, p. 71.

- ↑ Haldon 1990, pp. 70–78, 169–171; Haldon 2004, pp. 216–217; Kountoura-Galake 1996, pp. 62–75.

- ↑ Cameron 2009, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Cameron 2009, pp. 167–170; Garland 1999, p. 89.

- ↑ Parry 1996, pp. 11–15.

- ↑ Cameron 2009, p. 267.

- ↑ Mango 2007, pp. 259–260.

- ↑ Nicol 1988, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Louth 2005, p. 291; Neville 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Cameron 2009, pp. 138–142; Mango 2007, p. 60.

- ↑ Cameron 2009, pp. 157–158; Neville 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Neville 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Neumann 2006, pp. 869–871.

- ↑ Chrysos 1992, p. 35.

- ↑ Antonucci 1993, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Antonucci 1993, pp. 11–13; Seeck 1876, pp. 31–33

- ↑ Bury & Philotheus 1911, p. 93.

- ↑ Dennis 1985, p. 125.

- ↑ Obolensky 1994, p. 3.

- ↑ Troianos & Velissaropoulou-Karakosta 1997, p. 340

- ↑ Browning 1992, pp. 97–98

- ↑ Anastos 1962, p. 409.

- ↑ Alexander Jones, "Book Review, Archimedes Manuscript" American Mathematical Society, May 2005.

- ↑ "Pendentive | architecture". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Field, J. V.; Wright, M. T. (22 August 2006). "Gears from the Byzantines: A portable sundial with calendrical gearing". Annals of Science. 42 (2): 87. doi:10.1080/00033798500200131.

- ↑ "Anonymous, Byzantine sundial-cum-calendar". brunelleschi.imss.fi.it.

- ↑ "Sundial info" (PDF). academy.edu.gr. คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 10 August 2017. สืบค้นเมื่อ 1 March 2018.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Partington, J.R. (1999). "A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder". The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 13.

- ↑ Prioreschi, Plinio. 2004. A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine. Horatius Press. p. 42.

- ↑ Pevny, Olenka Z. (2000). "Perceptions of Byzantium and Its Neighbors: 843–1261". Yale University Press. pp. 94–95.